|

American

Whiskey

June 1, 2001: One Hundred Years of Bottled in Bond |

THE STORY OF BOURBON Whiskey is a story of evolution. What we now know as bourbon wasn't invented by a single maker, but developed slowly from the home-made whiskey produced by the farmers who grew the corn it was made from. As commercial whiskey production became established, one important step on the way to today's bourbon was a way to provide universally recognized quality standards and to encourage distillers to conform to them. In the earliest days of whiskeymaking both quality control and product reputation were entirely in the hands of the retailer. The customer was unaware of who distilled the bourbon he was drinking, and really didn’t care; he held the retailer completely responsible for his satisfaction. It was not unlike ordering a cup of coffee in a restaurant today... you’re usually not concerned with what brand of coffee the restaurant uses as long as it tastes good. When distillers began to develop competitive reputations, though, it became important to deal with product quality control. And it certainly wasn't uncommon for retailers to refill a popular distiller’s branded barrel with cheaper, inferior whiskey, and fill customers’ bottles from that.

The consumer product world of the mid- to late-19th century was very unlike today's landscape. There were no laws or regulations to ensure that the product purchased was what the label claimed it was. The purchaser of a bottle of whiskey, or a can of tuna, or any other product for that matter, had nothing but the retailer's word as to whether it really contained that product. Toward the end of the century, public sentiment was beginning to demand public legislation that would provide some safety, but these pure food and drug laws would still be decades in arriving.

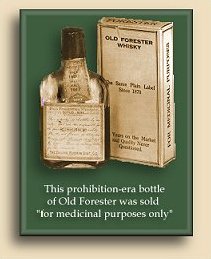

Two successful predecessors of the pure food laws were both ideas originally

developed in and for the American whiskey industry -- or at least the honest,

quality-oriented minority of it. In 1870, George Garvin Brown began bottling

Old Forester and selling it, mainly to physicians and druggists.

Other

whiskey dealers had sold bottled product before, but Brown made Old Forester

available only in individually sealed bottles, thus ensuring

that the product purchased was indeed the product received. Eliminating the

opportunity for point-of-sale deception and cheating did not endear Brown

with retailers, and many chose not to stock his product rather than give

up that lucrative practice. But the medical profession, and reputable

tavern-keepers, who depended on quality, more than made up for that. And the

idea caught on quickly with other manufacturer's, both in and beyond the

whiskey industry. Before long, the public wanted little to do with

any consumer product that wasn't sealed and labeled. Labels

and trademarks have been around for centuries, but it was at this point that

the concept really took off in the public marketplace.

Other

whiskey dealers had sold bottled product before, but Brown made Old Forester

available only in individually sealed bottles, thus ensuring

that the product purchased was indeed the product received. Eliminating the

opportunity for point-of-sale deception and cheating did not endear Brown

with retailers, and many chose not to stock his product rather than give

up that lucrative practice. But the medical profession, and reputable

tavern-keepers, who depended on quality, more than made up for that. And the

idea caught on quickly with other manufacturer's, both in and beyond the

whiskey industry. Before long, the public wanted little to do with

any consumer product that wasn't sealed and labeled. Labels

and trademarks have been around for centuries, but it was at this point that

the concept really took off in the public marketplace.

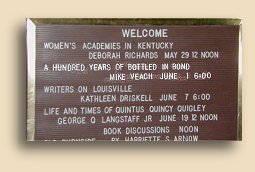

The Bourbon whiskey industry's second big contribution was the passing, in

1897, of the Bottled-in-Bond Act, and the one hundredth anniversary of this

event is what we are celebrating here this evening at the headquarters of

Louisville's famous Filson Historical

Society. Now, we know what you're thinking... John and Linda, are

you sure you don't mean the Filson Procrastinators' Society?

Shouldn't this celebration have occurred in, oh say, 1997? Oh

ye of little faith; of course one of the first things covered was why we

are celebrating, in 2001, the 100th anniversary of an event that took place

in 1897. The answer simply demonstrates the time warp that bourbon distillers

must learn to deal with. You see, besides meeting all the other criteria

specified in the act, bonded whiskey must be stored in a federally bonded

warehouse for a minimum of four years. Thus, the first bottle of Bottled-In-Bond

bourbon was indeed actually filled in

1901.

The idea for this evening was born when Filson Society historian and special collections assistant Mike Veach received a real prize - an unopened quart bottle of Old Taylor Bottled in Bond Bourbon from 1918. Still very clear and drinkable, Mike wanted to do something special with it, and he came up with the idea for an invitational tasting comparing pre-prohibition bourbon with modern bourbon. It would be a fund raising event for both the Filson Historical Society and also the Oscar Getz Museum of American Whiskey in Bardstown. Three months, and a lot of work and organizing, later, and they are ready to for us to enjoy and celebrate "One Hundred Years of Bottled-In-Bond". Representatives of some the world's most famous bourbon producers are here tonight. And so are several more very historic, authentic, and rare examples of American bourbon as the product has developed through the twentieth century. We will learn about them all tonight in a way that no amount of reading could ever duplicate...

The

evening began with the introductions, by Mark Wetherington, the Filson Historical

Society Director, of Mike and his co-host for the evening, Lincoln Henderson,

master distiller for Brown-Forman (Old Forester, Early Times, Labrot &

Graham, and Jack Daniel). The tasting was done in chronological order, starting

from the oldest to present. All of the bourbons we tasted demonstrated how

bourbon has changed over the years and also in what ways it has remained

constant. Most importantly, everything was related in some way to the 1897

Bottled-in-Bond Act and its effects on the whiskey industry.

The

evening began with the introductions, by Mark Wetherington, the Filson Historical

Society Director, of Mike and his co-host for the evening, Lincoln Henderson,

master distiller for Brown-Forman (Old Forester, Early Times, Labrot &

Graham, and Jack Daniel). The tasting was done in chronological order, starting

from the oldest to present. All of the bourbons we tasted demonstrated how

bourbon has changed over the years and also in what ways it has remained

constant. Most importantly, everything was related in some way to the 1897

Bottled-in-Bond Act and its effects on the whiskey industry.

The discussion then turned to what the Bottled In Bond act was, and why it was so important for both the bourbon whiskey industry and as the basis for the Pure Food and Drug laws that would later make the use of non-locally produced products safe for consumers.

Problem was, not everything sold in bottles labeled "Bourbon" was really

bourbon. Or even what we’d call whiskey today. There was nothing illegal

about selling anything as whatever the seller wanted to call it. A

whiskey dealer could put watered-down battery acid in a bottle, add tobacco

juice to color it, a little vanilla, a little mint, and then label the whole

mess, "Fine Old Bourbon". And he'd be anything but alone. In congressional

hearings in the last decade of the 1800's, during the discussions that led

to an official federal definition of whiskey, it was testified that less

than 2% of all bourbon whiskey sold would qualify as whiskey at all. This

didn’t apply only to bourbon, of course. Almost nothing a consumer purchased

was really what the label said it was, and in many cases it was downright

dangerous. Laws to protect people from disreputable entrepreneurs were still

several years off, but the desire of bourbon distillers to ensure dependable

standards laid the basis for them. All the straight bourbon makers wanted

was a way to distinguish their product from what was called "rectified" whiskey.

Rectifying is the process of mixing various whiskeys together to get a consistent

quality product. Originally many brand-name bourbons, including Old Forester,

were rectified whiskey. Even today, some of the finest bourbons available

are rectified, although we don’t call them by that term. And the reason

we don’t call them that is that "rectified whiskey" has become an epithet

that can also mean, "a beverage, containing little or no whiskey whatever,

made up from chemicals, flavorings, and colorings".

By

the time Colonel Edmund Haynes Taylor and his friend, Secretary of the Treasury

John G. Carlisle began drumming up support for the Bottled in Bond Act, nearly

all of the "bourbon" sold contained no bourbon at all. If there had been

truth-in-labeling laws, most brands would need to have been labeled, "Old

Tobacco and Iodine". But those laws didn’t exist yet. Such laws were

unthinkable at that time – they would have constituted government meddling

in private affairs. The Bottled in Bond Act didn’t limit or prohibit

anything; it just allowed the distillers of bonded whiskey to make the public

aware of that fact and what it meant to the consumer.

By

the time Colonel Edmund Haynes Taylor and his friend, Secretary of the Treasury

John G. Carlisle began drumming up support for the Bottled in Bond Act, nearly

all of the "bourbon" sold contained no bourbon at all. If there had been

truth-in-labeling laws, most brands would need to have been labeled, "Old

Tobacco and Iodine". But those laws didn’t exist yet. Such laws were

unthinkable at that time – they would have constituted government meddling

in private affairs. The Bottled in Bond Act didn’t limit or prohibit

anything; it just allowed the distillers of bonded whiskey to make the public

aware of that fact and what it meant to the consumer.

So what was bonded whiskey? Well, it was (and still is) whiskey that was stored in a federally bonded warehouse, where taxes didn’t have to be paid on it until it was bottled and removed for sale. In order to qualify for this tax relief, the whiskey had to meet certain requirements, and among these were that it had to be legally-defined straight whiskey, distilled in a single season by a single distillery, and bottled at 100 proof. It also had to be stored in the bonded warehouse for four years before bottling. This, of course, didn’t guaranty high quality, but it did guaranty that the product was really whiskey. And the federal government (which was popularly accepted as a respected authority) would put its own green seal on every bottle.

There were common recipes for rectified "bourbons", and many taverns made

up their own. Our tasting began with a fun experiment that Mike and Lincoln

"cooked up" just for this occasion.

Mike had discovered a recipe for

artificial bourbon in archives that dated from the 1860’s, which he

presented to Lincoln. Lincoln used the recipe to produce a bottle of instant

whiskey for us to taste. The Filson Society is currently featuring exhibits

and works about the Lewis & Clark Expedition, and in honor of that Lincoln

and Mike labeled their ersatz bourbon, "Old Clark and Lewis" (after the Gary

Larson cartoon reproduced on the label) and bottled it at a good, honest,

100 proof. Lincoln verified to all that it had been aging since about 9:00

this morning. The color was deep red-brown and actually was quite appealing.

The flavor was not as rank as most of us expected, although it certainly

didn’t taste anything like bourbon whiskey. John says it reminded him

of port wine, but at a much higher alcohol content. Linda was reminded of

cough syrup.

Mike had discovered a recipe for

artificial bourbon in archives that dated from the 1860’s, which he

presented to Lincoln. Lincoln used the recipe to produce a bottle of instant

whiskey for us to taste. The Filson Society is currently featuring exhibits

and works about the Lewis & Clark Expedition, and in honor of that Lincoln

and Mike labeled their ersatz bourbon, "Old Clark and Lewis" (after the Gary

Larson cartoon reproduced on the label) and bottled it at a good, honest,

100 proof. Lincoln verified to all that it had been aging since about 9:00

this morning. The color was deep red-brown and actually was quite appealing.

The flavor was not as rank as most of us expected, although it certainly

didn’t taste anything like bourbon whiskey. John says it reminded him

of port wine, but at a much higher alcohol content. Linda was reminded of

cough syrup.

We then sampled the bottle of pre-prohibition Old Taylor bourbon, bottled

in bond, which had been made in 1913 and bottled in 1918, and which inspired

this evening's affair. Golden in color and absolutely crystal clear, it had

a wonderful aroma and flavor. Surprisingly, it didn’t have any of the

characteristics we've come to call "old whiskey

flavor".

We then had a taste of Old Taylor bourbon of the type sold as medicinal whiskey

during prohibition. This whiskey was made in 1917 and bottled in 1933. The

16 years spent aging in wood (over three times as long as was intended when

it was put into the barrel) really showed in both the deep color and the

over-oaky flavor. It also had another subtle flavor that both Mike and Lincoln

characterized as typical of medicinal whiskey. Another prohibition whiskey

we tried was Gibson Rye, made in 1916 and bottled in 1933. Gibson was a

Pennsylvania distiller, so we were anticipating a chance to try real Monongahela

Rye the way it was supposed to taste.

As

John said, "Uh, I don’t think so! At least I hope it tasted better that

that". Easily the winner of the "worst in show" award, it was almost bitter

with oak flavor and the "under"tones were so dominant that they completely

overpowered any rye flavor that might once have been present.

As

John said, "Uh, I don’t think so! At least I hope it tasted better that

that". Easily the winner of the "worst in show" award, it was almost bitter

with oak flavor and the "under"tones were so dominant that they completely

overpowered any rye flavor that might once have been present.

Next we tasted a brand called Bankers and Brokers. This was a bonded bourbon made by Pappy Van Winkle’s Stitzel-Weller distillery in 1936 and bottled in 1941. It was one of the first whiskeys distilled in the new plant after Prohibition. This wheat-style bourbon was very pleasant and we remarked to Julian Van Winkle and his sister Sally Campbell, who were present, that it reminded us a lot of Julian’s current products.

We finished the tasting off with a sample of currently made Old Forester, a bourbon which meets all the criteria for bonded whiskey (although it no longer is stored in bonded warehouses and doesn’t use the term on the label any longer). Always one of our personal favorites, today’s Old Forester is every bit as fine a bourbon as any of the classics we tried, and considerably better than some.

During the course of the evening, Mike announced (to an audience largely

made up of professional historians) what he has named "the Lipman theory"

of how the bourbon name originated. Although John's idea goes into greater

detail, the general concept is that bourbon, the liquor, might not have been

named for Bourbon County in Kentucky (Virginia at that time) from which it

was once shipped, which is the commonly accepted belief. The theory then

goes on to speculate that bourbon, the liquor, was not originally intended

to be a type of whiskey at all. Which would explain why it has very little

similarity to Scotch or Irish whisky. John suspects that bourbon was originally

made, from whiskey, to be a liquor reminiscent of French cognac. And that

it was successfully marketed to French people in New Orleans as "Bourbon",

a cognac-like red, oaky, sweetish liquor named for the French royal family,

similar to the way Napoleon brandy is named. This idea has fascinated Mike,

and his announcement of it at the Filson Historical Society has lent credence

to it.

The

reaction was interesting. We would have expected the idea to be ignored

completely, or at the most maybe a polite chuckle or two might have been

heard. Instead there was a great deal of mumbling and head-turning. Some

expressions almost of shock were heard. It will be interesting to see what

happens with this idea as a result of Mike’s announcement.

The

reaction was interesting. We would have expected the idea to be ignored

completely, or at the most maybe a polite chuckle or two might have been

heard. Instead there was a great deal of mumbling and head-turning. Some

expressions almost of shock were heard. It will be interesting to see what

happens with this idea as a result of Mike’s announcement.

When the "show" part of the evening ended, we all adjourned to another room

for informal discussions and visiting around a table filled with fruits and

berries and snack vegetables, as well as several examples made with Kentucky

bourbon.

There

were bourbon chocolates and Kentucky smoked ham (on tiny biscuits) and Julian

brought samples of the wonderful smoked fish one of his customers makes using

his Old Rip Van Winkle bourbon. John spoke a lot with Lincoln (who, we learned,

is nearly as much a fan of our website as we are of his bourbon) and he,

Mike, and John got into a hilarious conversation in which they redesigned

Old Forester's distilling processes. Lincoln even took written notes on what

we’d like the new barreling proof to be. As we've mentioned before about

events like this, John compares the feeling with getting a chance to jam

with Eric Clapton.

There

were bourbon chocolates and Kentucky smoked ham (on tiny biscuits) and Julian

brought samples of the wonderful smoked fish one of his customers makes using

his Old Rip Van Winkle bourbon. John spoke a lot with Lincoln (who, we learned,

is nearly as much a fan of our website as we are of his bourbon) and he,

Mike, and John got into a hilarious conversation in which they redesigned

Old Forester's distilling processes. Lincoln even took written notes on what

we’d like the new barreling proof to be. As we've mentioned before about

events like this, John compares the feeling with getting a chance to jam

with Eric Clapton.

During this part of the evening, we met Joe Castro, who was also attending. Joe is the world-renowned master chef at the Brown Hotel’s famous English Grill. When I told him we were staying at the Brown, he arranged for a hotel shuttle to pick us up when we chose to return to our room.

Lincoln called us aside and said that he would be unable to join us, due to prior commitments, but he had made dinner arrangements for Mike and ourselves at the English Grill, with his compliments. We were stunned. Dinner was spectacular; Linda ordered a smoked chicken breast entree and I selected the grilled filet. Both were magnificently prepared and served. Dessert was a soufflé that was so light you almost needed to hold it down. Our waiter broke the top and poured in warm custard sauce from a silver boat. The only thing that could have made the meal more enjoyable would have been if Lincoln or Joe or both had been able to join us.

![]()