American

Whiskey

Rye Distilleries of Eastern

Pennsylvania & Maryland

May

3,

2003 |

|

|

|

The Baltimore Pure Rye Distilling Co. Dundalk, Maryland |

||

IN THE 1930's, shortly after the 18th amendment was

repealed, two distilleries were built in the countryside east of Baltimore. The

area is known as Dundalk.

The topsy-turvy shuffling of market positions that

marked the post-prohibition scramble is well illustrated by these two plants,

located virtually next-door to one another.

The topsy-turvy shuffling of market positions that

marked the post-prohibition scramble is well illustrated by these two plants,

located virtually next-door to one another.

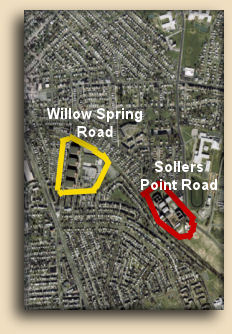

One distillery was built on farm land just off Sollers Point Road in the 1930s.

It's hard to believe today, but the population of Dundalk at that time was less

than 8,000, mostly employees of the Maryland Steel Company at nearby Sparrows

Point.

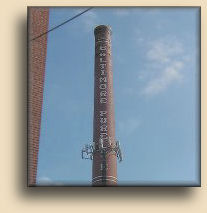

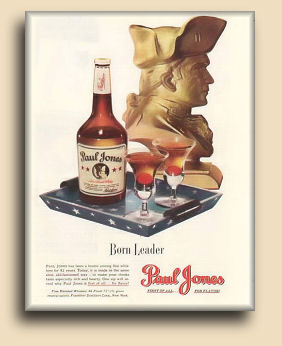

The distillery was the Baltimore Pure Rye distillery, and the brick smokestack

bearing its name still stands. But the distillery it stands over is known to

most people as Seagram's. Baltimore Pure Rye closed in 1957, and Seagram's

purchased it to produce Paul Jones and Four Roses. This is somewhat confusing,

since Seagram's bought these brands as part of their purchase of Frankfort

Distillery in the early 1940s.

Frankfort Distillery was not single plant, but a

Louisville-based company owned by the Paul Jones Company, which owned a number

of distilleries and brands. Among the brands was Four Roses, and among the

distilleries was the other Dundalk plant, located on Willow Spring Road, around

the corner from Baltimore Pure Rye. Of course, the purchase of Frankfort

Distillery included that site as well, and they were already running their

original Baltimore distillery, Calvert, not far away.

Frankfort Distillery was not single plant, but a

Louisville-based company owned by the Paul Jones Company, which owned a number

of distilleries and brands. Among the brands was Four Roses, and among the

distilleries was the other Dundalk plant, located on Willow Spring Road, around

the corner from Baltimore Pure Rye. Of course, the purchase of Frankfort

Distillery included that site as well, and they were already running their

original Baltimore distillery, Calvert, not far away.

It appears, from a 1988

study of local landmarks by the Baltimore County Landmarks Preservation

Commission, that the site had also belonged for a time to National Distillers

Products, although it isn't clear when, and the commission points out that (at

least by 1988) it was generally known as the Seagram distillery. The trademark

the Baltimore Pure Rye used, BPR, was registered to them (and not to anyone else

since) in 1944, having been used since 1942.

It appears, from a 1988

study of local landmarks by the Baltimore County Landmarks Preservation

Commission, that the site had also belonged for a time to National Distillers

Products, although it isn't clear when, and the commission points out that (at

least by 1988) it was generally known as the Seagram distillery. The trademark

the Baltimore Pure Rye used, BPR, was registered to them (and not to anyone else

since) in 1944, having been used since 1942.

What the distillery had been doing

since being built in the '30s is not clear. Perhaps that was when National

Distillers was involved.

What the distillery had been doing

since being built in the '30s is not clear. Perhaps that was when National

Distillers was involved.

The Seagrams company appears to have bottled Four Roses and Paul Jones whiskeys

at both locations, eventually closing this one in 1989 and selling the Willow

Springs unit to Montebello Distillery, which operates the bottling line to

produce cordials and liqueurs by contract, by 1992.

Again, all of these dates and the order of progression are based on conflicting

and sometimes contradictory statements.

Marketers in general, in especially in

the beverage industry, have a tendency to immediately claim the entire history

of whatever entity they've just purchased the the rights to; they rarely

acknowledge even the existence of another company, let alone whatever

relationship they may have had concerning a recently-purchased brand. In many

cases, even the fact that ownership of a brand had ever changed hands is

obscured, the idea apparently being that unbroken lineage is a desirable

feature.

Marketers in general, in especially in

the beverage industry, have a tendency to immediately claim the entire history

of whatever entity they've just purchased the the rights to; they rarely

acknowledge even the existence of another company, let alone whatever

relationship they may have had concerning a recently-purchased brand. In many

cases, even the fact that ownership of a brand had ever changed hands is

obscured, the idea apparently being that unbroken lineage is a desirable

feature.

The Baltimore Pure Rye Distilling Company seems to have been a successful and

very resourceful organization, with an innovative marketing department that

wouldn't seem a bit out of place in today's beverage marketing world.

They

called their 98% rye mashbill RYE-E-RYE, and their label sported a trade-marked

proprietary logo offering assurance that BPR contains "Real RYE-E-RYE", not

unlike the American Dairy Association's "REAL" cheese logo.

They

called their 98% rye mashbill RYE-E-RYE, and their label sported a trade-marked

proprietary logo offering assurance that BPR contains "Real RYE-E-RYE", not

unlike the American Dairy Association's "REAL" cheese logo.

In addition to backing their claim to "purity" with actual numbers (the 2%

non-rye can be assumed to be malted barley necessary for fermentation), BPR's

label makes other claims of its product's superior technical innovations.

As we've seen before, nostalgia and an emphasis on the glories of past

distilling methods have been a dominant theme in alcohol beverage marketing from

the very beginning.

For

example, the phrase "pot distilled", or variations on it, is commonly seen,

although distillers tend to be a bit vague as to exactly what a pot still really

is. BPR's label text is no exception -- it proudly points out

that it's made "in the old-fashioned Maryland way" -- but it gets very specific

about its unique distilling process, which used what they called a

"three-chamber charge still".

For

example, the phrase "pot distilled", or variations on it, is commonly seen,

although distillers tend to be a bit vague as to exactly what a pot still really

is. BPR's label text is no exception -- it proudly points out

that it's made "in the old-fashioned Maryland way" -- but it gets very specific

about its unique distilling process, which used what they called a

"three-chamber charge still".

They also reference their use of new, charred

white oak barrels, a federal requirement for any whiskey labeled "straight", but

not often stated on the label.

They also reference their use of new, charred

white oak barrels, a federal requirement for any whiskey labeled "straight", but

not often stated on the label.

Another fact you rarely see on whiskey labels, at least before the

small-batch/single barrel marketing concept came about in the 1980's, is the

name of the master distiller. In the case of BPR, that was William E. Kricker

(1870-1959), who also happened to be the president of the Baltimore Pure Rye

Distilling Company.

The label proudly displays information about him, including

his photograph.

The label proudly displays information about him, including

his photograph.

Heck, even current labels describing distillers Elmer T. Lee, Jimmy Russell and

the late Booker Noe don't include their pictures.

BPR called itself "America's largest independent distillery".

Of course that's a claim open to interpretation, but it's not one that

would likely be made if the company's profile didn't have

at least a plausible impact on the industry.

We've had the pleasure of drinking four-year-old, eighty-six

proof BPR Pure Maryland rye whiskey (we're unsure when

this was made, probably in the early 1950's) and

it was certainly delicious. We get an impression of Bill

Kricker as a rugged individualist

with old-fashioned high quality standards, who was able

to maintain his product's and company's integrity through nearly twenty years in

a world of predatory giants and corporate wheeling and dealing.

The Baltimore Pure Rye Distilling Company closed in 1957. William E. Kricker

died on the 5th of February, 1959.

Seagram's then bought the distillery and operated it for thirty years, closing

it sometime after July 1989.

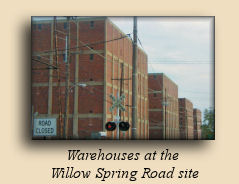

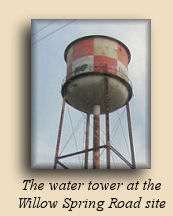

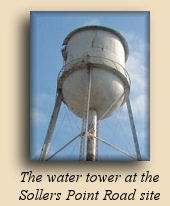

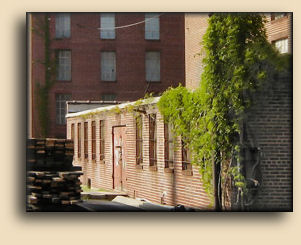

The property at the Sollers Point Road location is slowly being transformed from an abandoned eyesore to what will eventually be a modern industrial park. Currently it's being completely gutted out, and in the spring of 2003, our friend Chris Sigmon obtains permission from both the general contractor and the salvager for us to look it over and take photos. The Willow Springs Road location is still in use and visitors are not allowed, but we took a couple of shots from outside the site.

The following are thumbnail links. Click any of them to see larger pictures.