|

American

Whiskey

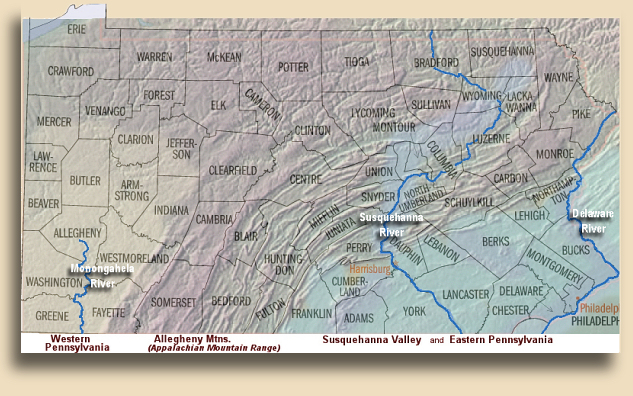

Rye Distilleries of Eastern

Pennsylvania & Maryland

IN MARCH OF 1946, Winston Churchill was

visiting Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. The occasion was his

acceptance of an honorary degree, and he used that opportunity to speak about

what he perceived as happening in Europe with the close of the second World War.

It was in that speech that Mr. Churchill famously warned the world that, from

“… Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an iron curtain has

descended across the Continent.”

He meant, of course, the European Continent. But

there is such a curtain dividing the North American Continent as well. Only,

this one is made of rock, covered with dirt and forests. It is a very tall

curtain, over half a mile high in some places, and very wide. It does not have

barbed wire and military troops to prevent or control crossing it; it is guarded

by gravity, a far more formidable opponent. It’s name is the Appalachian

Mountain Range, and it extends, virtually unbroken, over 1,600 miles from the

St. Lawrence River of Canada southwest-ward to Georgia and Alabama in the United

States. Even today there are few major highways that cross this wall in an

East-West direction, and even fewer that do so without spending many diverted

miles traveling North-South in the process. In the 17th and early 18th centuries

there were even fewer. Although the Great Conestoga Road between Philadelphia

and Lancaster (still on the eastern side of the mountains) was opened as early

as 1741, it would be another seventeen years before a thoroughfare to Pittsburgh

was completed.

The other major east-west route, the Cumberland

road, would connect Baltimore, by way of Maryland’s western outpost Cumberland,

to the Ohio River at Wheeling, in western Virginia. But that wouldn’t happen

until 1818.

The commercial whiskey industry in western

Pennsylvania had never been the target of the Federal authority-enforcement

action known as the Whiskey Rebellion. In fact, it’s probably safe to say that

the commercial distilleries (whose taxes and licensing were proportionate to

their capacity and who simply passed those costs on to their customers) could

not have been as successful had they needed to compete with hundreds of

independent distillers who were not being taxed. Their product, known as

Monongahela Rye, was unique and distinctive to their region and very different

from the rather harsh, clear spirit which was available east of the Alleghenies.

What it had more in common with was the aged, red-brown, New England rum so

beloved by the well-to-do tavern patrons and social leaders all up and down the

Atlantic coast. Many of the qualities for which Monongahela was appreciated

were the result of its long and arduous journey to market, whether by mule team

across those awful mountains or by flatboat down the Ohio and Mississippi

rivers, and then by ship from New Orleans. And the days and weeks of constant

rocking and jostling were often interspersed with long delays in storage

warehouses, waiting until seasonably impassable river sections or trails

cleared. These conditions were remarkably similar to those endured by New

England rum. Rum made in New England from molasses purchased in the West Indies

was shipped to the West African slave markets and exchanged for fresh slaves,

which were then sold to the West Indies sugar plantations in exchange for

molasses. The repeating cycle became known as the Triangle Trade. The

barrels of rum that were loaded aboard the ships in Rhode Island were the

property of the slave-agent, and were intended to be used as barter for

purchasing slaves. The number of slaves to be purchased was finite, there being

only so many that the ship could hold. A good agent would be able to fill the

ship for much less than all the rum he had available, and whatever wasn’t needed

would be his to sell for cash when the ship returned home. In the meantime, it

would have spent months sloshing around on a rocking ship, mostly in intense

tropical heat, followed by possibly a chilling few weeks on its way to New

England and perhaps further storage there. So, when New England rum was ordered

in a tavern, what was expected was a spirit that had a deep copper-brown color,

with the rich flavors acquired from all that barrel contact.

Around 1807 the notorious Triangle Trade came to

a sudden halt (officially, at least). And although traces of the trade continued

for much longer, New England rum, which was never financially feasible except

for being subsidized as pre-paid “leftovers” of the slave trade, disappeared as

an American consumable. Monongahela Rye whiskey, however, filled the need quite

nicely, and western Pennsylvania had a virtual monopoly on its production.

Not for long, of course. The same qualities that

resulted from West Pennsylvania’s remoteness could be achieved by alternate

means, some more legitimate than others. For example, barrels of whiskey could

be warehouse-stored intentionally for long periods. In fact, with the advent of

the steamboat and the railroad reducing the travel time from months to days,

that would become necessary. Today “aging” is the prescribed way of maturing

whiskey. And that method was available to wholesalers no matter which side of

the mountains they were on. Notice this listing in the Lebanon (Pennsylvania)

County Atlas for 1875:

|

|

|

Bomberger A. S.,

Owner of 20 acres of land, improvements thereon are a large frame house and

barn. Also, Proprietor of Bomberger's distillery, and Dealer in Liquors,

both Wholesale and Retail. Pure

Rye Rum to be had at the

lowest market price. PO, Schaefferstown, Lebanon co

|

|

|

Other methods of maturing and mellowing

liquor were available as well, including adulteration with coloring and

flavoring. Rye whiskey, red rye whiskey, was by far the dominant American spirit

through the second half of the 19th century, especially in eastern Pennsylvania

and in Maryland. Dozens of brands of “Pure Rye” whiskey competed with one

another, many of them renowned for their excellence and high quality. The

passage of national prohibition in 1919 is often given as the reason for their

demise, but the truth is that most of those brands – even the most

highly-respected names – vanished immediately after the passage of the Pure Food

and Drug Act in 1906.

The commercial distilleries of the west –

Overholt, Thompson, Large, Dillinger, Gibson, Guckenheimer – were not much

affected by all that. The Appalachians are not just tall; they’re wide as well –

up to 200 miles across at some points. And that provided a sort of cultural

insulation between West and East. As for settlers within that mountainous zone

in between, well, they made whiskey just like everywhere else, selling mostly

locally.

At least they did until civilization caught up

with them…

| |

August 30,

2005

The Frantz

Distillery

Somerset County

(Berlin or Meyersdale),

Pennsylvania |

About thirty miles northwest

of Cumberland (Maryland’s gateway to the frontier) lies the little town of

Meyersdale, Pennsylvania, whose population even today is around 2,473. According

to a Meyersdale Commercial newspaper article dated August 7th 1890, the area

around this community boasted no less than twelve whiskey distilleries.

We

learned this, and much other information, from archivist Cynthia Mason, of the Meyersdale public

library, who offered unlimited time to help us locate a completely different

distillery, which, unfortunately, there did not seem to be any records of (but

we’ll keep looking and update the site as we find new stuff!). To Ms. Mason we owe

most of the next paragraph… and then some! We

learned this, and much other information, from archivist Cynthia Mason, of the Meyersdale public

library, who offered unlimited time to help us locate a completely different

distillery, which, unfortunately, there did not seem to be any records of (but

we’ll keep looking and update the site as we find new stuff!). To Ms. Mason we owe

most of the next paragraph… and then some!

As I said, from the records Cynthia provided, it

seems that there were no less than a dozen distilleries in the Meyersdale/Berlin/Turkeyfoot

area by 1890. One of these was first built sometime before 1830, by a man named

Baer, about five miles southeast of what is now known as Berlin, Pennsylvania in

Somerset County. His was a small but commercial operation, selling locally. The

area was a land of thick forests; wood was cheap, selling for as little as a

dollar per hundred feet, and around 1850 a “mud-free” plank road was built from

Cumberland, Maryland, to West Newton, Pennsylvania. The road just happened to

run past the distillery, which provided a nice business in itself, and also

allowed word of the Baer Distillery to spread to Cumberland and from there to

Baltimore.

About

this time a man named D. Schultz bought the distillery and operated it into the

1900’s. It was then sold to a man named Minor, who in turn sold it to another

named (Walter?) Hawking – while all the time the distillery remained known as

“the Schultz Distillery”. An interesting note that we learned from the Berlin

Area Historical Society is that Hawking completely remodeled the plant,

installing pot stills and initiating “the same process as in making moonshine”,

including stirring the mash “until the boiling process began and then it was

capped to complete the evaporation process necessary for distilling”. This

description seems to apply to the type of pot distilling generally thought to

have been universal for small distilleries at that time; the more “modern”

method would have been to install a continuous (or “column”) still, such as the

type invented in the early 1830’s by Aeneas Coffey. That method is often

referred to as “cooking with steam”. About

this time a man named D. Schultz bought the distillery and operated it into the

1900’s. It was then sold to a man named Minor, who in turn sold it to another

named (Walter?) Hawking – while all the time the distillery remained known as

“the Schultz Distillery”. An interesting note that we learned from the Berlin

Area Historical Society is that Hawking completely remodeled the plant,

installing pot stills and initiating “the same process as in making moonshine”,

including stirring the mash “until the boiling process began and then it was

capped to complete the evaporation process necessary for distilling”. This

description seems to apply to the type of pot distilling generally thought to

have been universal for small distilleries at that time; the more “modern”

method would have been to install a continuous (or “column”) still, such as the

type invented in the early 1830’s by Aeneas Coffey. That method is often

referred to as “cooking with steam”.

The

August 1890 Meyersdale Commercial article pointed out that four of the twelve

distilleries mentioned used that method, which meant that the other eight

(including Schultz) did not. The

August 1890 Meyersdale Commercial article pointed out that four of the twelve

distilleries mentioned used that method, which meant that the other eight

(including Schultz) did not.

Hawking was very successful with this distillery.

During 1908 to 1910 there was much railroad construction and coal mining, and

that meant lots of hard-working, hard-drinking men. Hawking offered a delivery

service. He would fill a dray wagon with jugs of his whiskey (almost certainly

unaged, or he would have just dispensed it directly from the barrel) and make

his rounds to the different work camps. Again according to the Berlin Historical

Society’s bicentennial edition (1977), “There were rules. The least amount you

could buy was a gallon. After buying the prescribed amount you were then free to

purchase any amount extra, such as a pint or half gallon”.

It’s possible that

he made his fortune and retired in 1915, or perhaps there were internal

problems, but in that year the business was sold to a man named Leech, and its

name changed from Schultz to the Leech Distillery. For some reason

Leech was never able to maintain the quality level of his predecessor and before he

could get those problems worked out the entire industry was doomed by national

prohibition.

In 1933 the 21st amendment to the Constitution

brought an end to national prohibition, making the 18th the only constitutional

amendment ever to have been repealed. Shortly thereafter, a Pittsburgh man named

Frantz bought the remains of the old distillery, completely overhauled the

equipment and buildings, and began producing what is said to be some of the

finest whiskey ever made in the United States. Unfortunately, that didn’t last

long. Soon after the outbreak of World War II the Frantz Distillery was

pressed into service as a supplier of industrial alcohol used in making methyl

rubber.

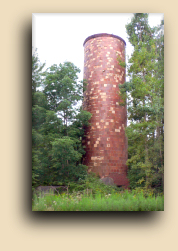

More

structures were added, including a 100-foot tiled tower for storing grain, which

still stands. At this time the distillery More

structures were added, including a 100-foot tiled tower for storing grain, which

still stands. At this time the distillery

was producing 2,500 gallons of alcohol

a day, working 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Potatoes were used for making

the industrial alcohol, and it was reported that every railroad siding in the

area was taken up with cars full of potatoes from all over the country. was producing 2,500 gallons of alcohol

a day, working 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Potatoes were used for making

the industrial alcohol, and it was reported that every railroad siding in the

area was taken up with cars full of potatoes from all over the country.

When

the war ended, the distillery’s prosperity continued, as the potato flour

production – some 30,000 pounds daily! – was sent to Germany as part of the

Marshall Plan. When

the war ended, the distillery’s prosperity continued, as the potato flour

production – some 30,000 pounds daily! – was sent to Germany as part of the

Marshall Plan.

In 1946 the old drier house caught fire and

burned down, ending the potato flour production. At the time, the Frantz

Distillery was listed as one of the largest industrial plants in Somerset

County. Regular whiskey production, which had resumed after the war, continued

until after Frantz’s death. Distilling operations ceased in 1952, although

warehousing and bottling continued until 1956.

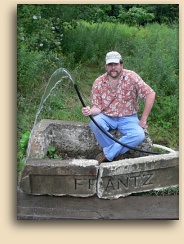

On our visit to the Frantz Distillery in 2005, we

are accompanied by our friend Sam Komlenic. Sam had been by here briefly a few

years ago, and what he most remembered was seeing someone driving along the road

pull to a stop next to a concrete box and a hose sticking out of the ground.

The

driver got out, opened his trunk, and pulled out a couple of empty plastic

gallon milk jugs, which he began filling from the hose. When Sam went over to

find out what was going on he learned that this was a direct tap to the spring

that fed the distillery. Apparently people in the area often come here and fill

up containers with the purest and best-tasting spring water you could ever

obtain. Of course, we have to immediately check to see if the “spring hose” is

still here, and it certainly is. The hose doesn’t turn off or on; water flows

through it constantly, just as it would if there were no hose. The

driver got out, opened his trunk, and pulled out a couple of empty plastic

gallon milk jugs, which he began filling from the hose. When Sam went over to

find out what was going on he learned that this was a direct tap to the spring

that fed the distillery. Apparently people in the area often come here and fill

up containers with the purest and best-tasting spring water you could ever

obtain. Of course, we have to immediately check to see if the “spring hose” is

still here, and it certainly is. The hose doesn’t turn off or on; water flows

through it constantly, just as it would if there were no hose. The constantly-moving stream, tapped into a larger pipe underground, is thus

perfectly clean, and the water is very delicious. We’re not sure of the purpose

for the concrete box you see in the photo (and which is cracked in two pieces),

but we think it may have been for the use of horses.

The constantly-moving stream, tapped into a larger pipe underground, is thus

perfectly clean, and the water is very delicious. We’re not sure of the purpose

for the concrete box you see in the photo (and which is cracked in two pieces),

but we think it may have been for the use of horses.

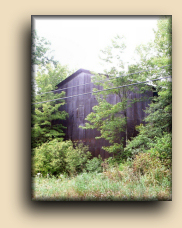

There are only a couple of buildings still

standing, the main one being what we think was once the office and bottling

house. A portion of it is now being used by a firm that manufactures iron

woodstoves. Other surviving structures include at least a portion of the tiled

storage silo, a corrugated-steel covered wooden Rick house, and (barely) a large

wooden building that may have been the distiller’s living quarters. That

building also has rooms that appear to have been individual apartments or

transient quarters. The rest of what we find here consists of partial walls and

foundations for several other buildings, mostly overgrown with weeds. A portion of it is now being used by a firm that manufactures iron

woodstoves. Other surviving structures include at least a portion of the tiled

storage silo, a corrugated-steel covered wooden Rick house, and (barely) a large

wooden building that may have been the distiller’s living quarters. That

building also has rooms that appear to have been individual apartments or

transient quarters. The rest of what we find here consists of partial walls and

foundations for several other buildings, mostly overgrown with weeds.

|

![]()

![]()