American Whiskey

GHOSTS

of

WHISKIES

PAST

The

Louisville

Distilleries

Driving south on the Dixie Highway, you never even know you've left Louisville

until you start seeing the store signs. Shively Motors, The Bank of Shively,

Shively Center. The suburb of Shively, Kentucky is perhaps not as shabby

as the edges of Louisville we've just driven through, but it's been around

long enough that its post-war sparkle has faded more than a little

bit.

A sign on the left side of the road says you're passing the driveway that leads back to the very-much-alive Early Times distillery, and then you're at Ralph avenue and little more than a right turn away from one of the bourbon world's most beloved icons...

Old

Fitzgerald

~

The

Stitzel-Weller

Distillery

~

September

14,

2000

The end of World War II brought with it an end to the rationing and restrictions

that kept beverage alcohol production at a minimum.

The

post-war prosperity and expanding popularity that bourbon saw in the Fifties

and Sixties were some of the best times the industry ever had. Optimism about

the future, and a fear of being under inventoried as they were after

prohibition fueled a fury of overproduction.

The

post-war prosperity and expanding popularity that bourbon saw in the Fifties

and Sixties were some of the best times the industry ever had. Optimism about

the future, and a fear of being under inventoried as they were after

prohibition fueled a fury of overproduction.

Unfortunately,

by the end of the Sixties, the popularity of bourbon whiskey had begun to

level out and the Seventies and Eighties were tumultuous years in the American

whiskey business. In the summer of 1972, the Stitzel-Weller Distilling company

of Louisville, owned by the Van Winkle family and opened by its beloved

patriarch, Julian P. "Pappy" Van Winkle on Derby Day 1935, just after the

repeal of National Prohibition, was sold to Norton Simon for $20 million.

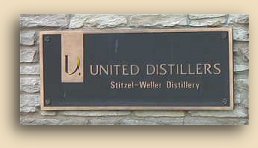

Norton Simon later sold it to Guinness of London, operating as United Distillers.

United, which owned several Scotch whisky distilleries, went shopping in

the USA the same way you might shop at a supermarket. They took a little

of this, all of that, some more of this other one, until they had accumulated

no less than seven American distilleries. In

1991 they built Bernheim, a modern, state-of-the-art facility at 17th and

Unfortunately,

by the end of the Sixties, the popularity of bourbon whiskey had begun to

level out and the Seventies and Eighties were tumultuous years in the American

whiskey business. In the summer of 1972, the Stitzel-Weller Distilling company

of Louisville, owned by the Van Winkle family and opened by its beloved

patriarch, Julian P. "Pappy" Van Winkle on Derby Day 1935, just after the

repeal of National Prohibition, was sold to Norton Simon for $20 million.

Norton Simon later sold it to Guinness of London, operating as United Distillers.

United, which owned several Scotch whisky distilleries, went shopping in

the USA the same way you might shop at a supermarket. They took a little

of this, all of that, some more of this other one, until they had accumulated

no less than seven American distilleries. In

1991 they built Bernheim, a modern, state-of-the-art facility at 17th and

Breckenridge Streets in Louisville and closed down everything else. Even

in their new plant, they only made whiskey for about seven years before selling Bernheim to Heaven Hill in 1999 and getting out of the bourbon-making business

entirely. "Out of the bourbon-making business" isn't the same, however,

as "out of the distillery business". In the wonderful world of bourbon,

many parts of the whole process are considered legally separate, and they're

often marketed that way. The "business" is distinct from the buildings and

equipment, as are the brand (label), the formula for making the brand, the

yeast, the rights to sell (in various places), and other factors. Including,

of course, existing stock. Which is often further complicated by the fact

that distilleries usually produce several brands from different ages and

mixtures of the same stock. The way it worked with Stitzel-Weller was pretty

simple for the sale to Norton Simon and to United Distillers; the seller took the whole package.

Breckenridge Streets in Louisville and closed down everything else. Even

in their new plant, they only made whiskey for about seven years before selling Bernheim to Heaven Hill in 1999 and getting out of the bourbon-making business

entirely. "Out of the bourbon-making business" isn't the same, however,

as "out of the distillery business". In the wonderful world of bourbon,

many parts of the whole process are considered legally separate, and they're

often marketed that way. The "business" is distinct from the buildings and

equipment, as are the brand (label), the formula for making the brand, the

yeast, the rights to sell (in various places), and other factors. Including,

of course, existing stock. Which is often further complicated by the fact

that distilleries usually produce several brands from different ages and

mixtures of the same stock. The way it worked with Stitzel-Weller was pretty

simple for the sale to Norton Simon and to United Distillers; the seller took the whole package.

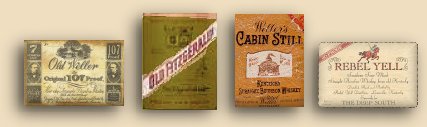

The

sale of Bernheim, however was more complicated, because it was divided among

at least three or four buyers, plus the seller retained portions. Of the

Bernheim brands that had been Stitzel-Weller, Heaven Hill bought only the

Old Fitzgerald label (and probably the formula and yeast). The Old Weller

brands were sold to Buffalo Trace, where they will now be produced. Rebel

Yell went to the David Sherman Company in St. Louis, Missouri. The existing

stock of all those brands is warehoused all together at the Stitzel-Weller

facility in

Shively.

The

sale of Bernheim, however was more complicated, because it was divided among

at least three or four buyers, plus the seller retained portions. Of the

Bernheim brands that had been Stitzel-Weller, Heaven Hill bought only the

Old Fitzgerald label (and probably the formula and yeast). The Old Weller

brands were sold to Buffalo Trace, where they will now be produced. Rebel

Yell went to the David Sherman Company in St. Louis, Missouri. The existing

stock of all those brands is warehoused all together at the Stitzel-Weller

facility in

Shively.

One ironic feature of the time lag in the way that bourbon is made and aged is that many of the longer-aged brands associated with Stitzel-Weller (Old Weller Antique, Centennial, Old Fitzgerald 1849, Very Special Old Fitz 12 year old) were actually made at Stitzel-Weller. And there's still enough old stock that we'll all be drinking the nectar of that abandoned old all-copper still for years to come.

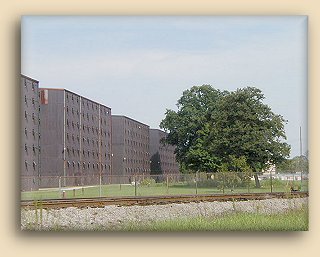

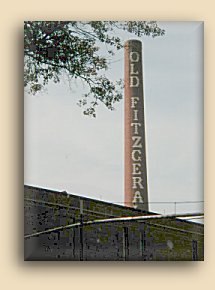

As we round a slight curve on Ralph street it's pretty obvious where the distillery is. The seven-story warehouses are easy to spot, as is the famous brick chimney with "OLD FITZGERALD" displayed upon it. We make a right turn on Fitzgerald Road (another slight give away) and soon find ourselves in front of the main gate.

When we first laid eyes on the remains of Old Crow, we had no idea what to

expect. We hadn't seen any old abandoned distilleries before, and there weren't

really a lot of photos. Seeing Stitzel-Weller

is a different matter altogether. This was a working distillery at the time

when most of the books we learned from were written. Among more recent works

is Sally Van Winkle Campbell's delightful memoir, But Always Fine

Bourbon. Pappy Van Winkle's granddaughter

intended

to write a grown-up story about her father and grandfather, and how they

built a proud business by making a fine product the best way they possibly

could and just letting the world know it. But the book manages to go way

beyond that, presenting a little-girl's view of growing up in a time when

families were proud of what they'd taken two and three generations to build

-- whether a railroad, an automobile company, or a distillery. The book is

beautifully published, with thick covers, carefully selected and laid typography

and a variety of papers including translucent leaves. It is also blessed

with some of the most gorgeous photography imaginable, rivaling the best

of Ansel Adams' work. There is such a beauty and a life to the pictures...

intended

to write a grown-up story about her father and grandfather, and how they

built a proud business by making a fine product the best way they possibly

could and just letting the world know it. But the book manages to go way

beyond that, presenting a little-girl's view of growing up in a time when

families were proud of what they'd taken two and three generations to build

-- whether a railroad, an automobile company, or a distillery. The book is

beautifully published, with thick covers, carefully selected and laid typography

and a variety of papers including translucent leaves. It is also blessed

with some of the most gorgeous photography imaginable, rivaling the best

of Ansel Adams' work. There is such a beauty and a life to the pictures...

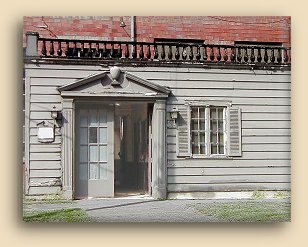

...And such a sadness and despair to the scene in front of us. The front door of the distillery building itself hangs open, allowing us to see into the abandoned interior. Gray paint peels from the clapboard siding in huge flakes.

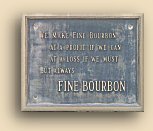

There were signs and slogans here once, all over the property.

Clever ones, like this faux warning,

Nature and the old-time 'know how' of a Master Distiller get the job done here...

This is a Distillery - not a whiskey factory

"Just a taste is all we ask...

it's all we've

ever needed!".

and

At a profit if we can

At a loss if we must

But always

FINE BOURBON

They're

still full of lots of barrels of fine, aging Stitzel-Weller and Bernheim

bourbon. A sign at the main gate suggests that trucks enter through the back

gate on Tucker Avenue. And that's where we head next, turning at the Shively

Rod and Custom Shop, where '58 Chevvies are still lowered and fitted with

lake pipes, frenched headlights, and tuck'n'roll upholstery. There is a guard

at this gate, and that's the only person we see. But trucks still move barrels

out of here, although now that Heaven Hill owns the Bernheim distillery they

probably no longer move them

in.

They're

still full of lots of barrels of fine, aging Stitzel-Weller and Bernheim

bourbon. A sign at the main gate suggests that trucks enter through the back

gate on Tucker Avenue. And that's where we head next, turning at the Shively

Rod and Custom Shop, where '58 Chevvies are still lowered and fitted with

lake pipes, frenched headlights, and tuck'n'roll upholstery. There is a guard

at this gate, and that's the only person we see. But trucks still move barrels

out of here, although now that Heaven Hill owns the Bernheim distillery they

probably no longer move them

in.