American Whiskey |

||

|

A.

Guckenheimer & Bros. Distillery We found it! Here it is! No, wait... it's HERE No, it's over HERE!!

|

|

|

BUFFALO CREEK empties into the Allegheny river right about where four Pennsylvania counties (Allegheny, Butler, Armstrong, and Westmoreland) come together near the pretty little town of Freeport.

This tiny Armstrong County community is home to around 530 families, none of whom appear to be aware there was once a very important whiskey distillery here. In fact, there appears to have been at least two, both of them known as the Guckenheimer distillery. Except when they were called the Pennsylvania Distilling Company.

In spring of 2003, we spent much of an afternoon exploring, repeatedly,

all eight or so blocks of Freeport in search of any clue to either

distillery's former location. To no avail. We finally gave up and moved

on, vowing to one day learn more about the A. Guckenheimer & Bros.

Company and the distillery where they produced Good Old Guckenheimer,

perhaps the most prestigious of the so-called "Monongahela" whiskeys.

Why "so-called"? Well, the name Monongahela comes from the

Monongahela River Valley, which came to be identified with a specific type

of whiskey. Made from rye grain, with little or no corn (maize), it

featured a deep, reddish-brown color and a distinctive flavor. East Coast rye whiskey, sometimes called Maryland rye (although also including rye from Pennsylvania east of the Appalachian

Mountains) was not really the same kind of spirit,

often being unaged or very young, and usually being made from both rye and

corn grains. Bourbon, a whiskey also said to be

named for the location of its origins, is made mostly from corn and has a

distinctive flavor of its own.

rye (although also including rye from Pennsylvania east of the Appalachian

Mountains) was not really the same kind of spirit,

often being unaged or very young, and usually being made from both rye and

corn grains. Bourbon, a whiskey also said to be

named for the location of its origins, is made mostly from corn and has a

distinctive flavor of its own.

Most of the "bourbon" distilleries were not actually located in what is today Bourbon county (although the county was once much larger); in fact none of them are. Likewise, most of the western Pennsylvania rye distillers were not located along the Monongahela River (locally, "The Mon"). One of the best-known, Old Overholt, was built on a tributary of "The Mon", the Youghiogheny River ("The Yock"). Another important river in this region is the Allegheny, which flows from the mountains of the same name and ends up combining with "The Mon" to form the Ohio River. Where that happens is called Pittsburgh, and a great number of fine so-called Monongahela distilleries once dotted the banks of the Allegheny upstream of Pittsburgh. Among them was that of Asher Guckenheimer & Brothers.

And, no, there isn't a similar name for the Allegheny

River, such as "The Alley".

People here just call it the Allegheny River.

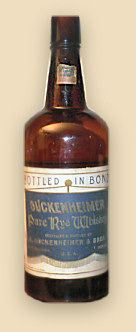

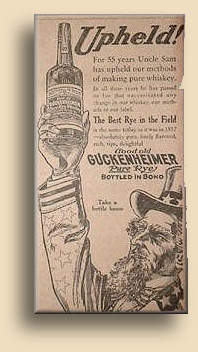

Monongahela rye isn't a whiskey for the debonair. It's pretty rough 'n' tumble stuff, the character of which was shaped by it's long and arduous journey from where it was distilled to where it was consumed. Locally, the whiskey was probably drunk unaged, the same as any other whiskey was at that time. The product that made its way to Baltimore, New York, Boston, and Philadelphia, though, had developed a character more similar to what we, today, expect whiskey to have... except a bit less genteel. But then, the big-city tavern patrons who bought it weren't drinkers of "whiskey" anyway. That was a drink for country-bumpkins and the unsophisticated. Fashionable tavern patrons who bought Monongahela most likely thought it was a type of rum. Later, when the product began to be recognized for what it was, Monongahela began to lose some of its social appeal. But not all brands. Guckenheimer Pure Rye Whiskey held a reputation as an award-winning liquor and was sold as top-shelf liquor throughout its entire pre-prohibition existence.

That was before it went on to become part of the Schenley empire, which itself began with the acquisition of many of the Allegheny Valley distilleries.

And that was before it went further on to become a product of the American Distilling Company in Pekin, Illinois, and the Heaven Hill Distilling Company in Bardstown, Kentucky.

But long before any of this happened , there was Thomas Bell.

Or was that Thomas Bole?

Or maybe John Bole, and Thomas McGill?

Or John Moyer

Or Henry S. Weaver.

Or Williamson & Rhey

Or P. McGonigle & Son

Or McGonegal, Helmbold & Co.

It all depends on whose stories you're reading, and what order you're

reading them in.

Let's take a look at a few...

According to "The Story of Pittsburgh" published by the Pittsburgh

Gazette-Times in 1908 (available online through the

Penn State University Library Digital Collection), one of several early distillers along the Allegheny

River was Thomas Bell, who built his distillery in Freeport in 1846.

The whiskey that Bell produced is said to have enjoyed a regional reputation for excellence, and when Asher

Guckenheimer and his half-brother,

Samuel Wertheimer, established a

Pittsburgh mercantile shop in 1857, they became known for their

private brand of rye whiskey, which they obtained from Bell. Bell's

operation was very small, only about 2,000 barrels annual production, and

the Guckenheimer brothers contracted Bell's entire output. Although

Guckenheimer was Bell's sole customer, the Gazette-Times doesn't indicate

whether Bell was the merchant's only provider.

Samuel Wertheimer, established a

Pittsburgh mercantile shop in 1857, they became known for their

private brand of rye whiskey, which they obtained from Bell. Bell's

operation was very small, only about 2,000 barrels annual production, and

the Guckenheimer brothers contracted Bell's entire output. Although

Guckenheimer was Bell's sole customer, the Gazette-Times doesn't indicate

whether Bell was the merchant's only provider.

What

they do say is that, upon Thomas Bell's death, they purchased the

distillery itself, although the year of that event isn't given. Apparently

the small capacity of the distillery immediately proved inadequate, however,

and they began designing and building a much more pretentious facility

with greatly-increased capacity and all modern equipment. Nothing more is

said of the Thomas Bell distillery, but the Gazette-Times article implies

that the new plant was not built at the same location.

What

they do say is that, upon Thomas Bell's death, they purchased the

distillery itself, although the year of that event isn't given. Apparently

the small capacity of the distillery immediately proved inadequate, however,

and they began designing and building a much more pretentious facility

with greatly-increased capacity and all modern equipment. Nothing more is

said of the Thomas Bell distillery, but the Gazette-Times article implies

that the new plant was not built at the same location.

There was further expansion in 1868. In that year the Guckenheimer Brothers purchased a distillery in Upper Sandusky, Ohio, which produced a brand named "Wyandotte". The logistics of trying to manage it from Pittsburgh, however, were too great and they quickly sold it off.

In 1876 they purchased the McGonegal, Helmbold, & Co. distillery in Buffalo Township, Butler county, which was doing business under the name Pennsylvania Distilling Company. That distillery produced a regionally successful brand named "Montrose" which also became a nationally distributed brand of no small fame. Shortly after the new Freeport distillery was completed, the Buffalo Township plant burned down and was immediately replaced with a new facility built along the same lines as the Freeport site. The new Montrose distillery produced about 12,000 barrels annually.

The Gazette-Times notes that Asher Guckenheimer operated

these two distilleries until his death in 1893, at which time the business

passed to his partners, his son, and their sons. There is no mention of

any other distilleries being involved.

The

Robert E. Snyder Whiskey Brand Database,

basically tracks the same information, although it puts the Thomas Bell

distillery's output at around 6,000 barrels a year, or about triple the

Gazette-Times' estimate.

The database, one of the most extensive existing, doesn't mention the Pennsylvania Distilling

Company at all, nor can any reference to McGonegal, Helmbold, & Co. be

found there, but it does include

"Montrose" among the brands whose trademarks were registered by A.

Guckenheimer & Bros. Other brands registered to Guckenheimer were "Fairy

Breath", "Freeport", "Golden Cupid Rye",

and "Pennbrook."

Other brands registered to Guckenheimer were "Fairy

Breath", "Freeport", "Golden Cupid Rye",

and "Pennbrook."

Both of these sources mention that Guckenheimer took top honors at the

1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, scoring an incredible 99¼ points out of a possible

100. The Gazette-Times history also notes that theirs was the highest score

earned by any whiskey presented at the Exposition. 1893 was also the year Asher

Guckenheimer died, leaving the firm in the hands of his son, Isaac, and

his two half-nephews, Emanuel and Isaac Wertheimer. It appears to be

generally agreed that they successfully maintained Guckenheimer Pure Rye

as one of the most prestigious brands in America until it finally closed

in 1918.

Now that we have a pretty good idea of the Guckenheimer Bros. and their

whiskey, along comes the Buffalo Township chapter of

The History of Butler County,

Pennsylvania, published in 1895 by R. C. Brown Co., which makes no

mention at all of Thomas Bell, nor of a Guckenheimer distillery in Freeport,

describing Guckenheimer as being located in

Buffalo township, Butler county, across Buffalo Creek from Freeport. This

history describes the

site as consisting of one large brick distillery building and two bonded

warehouses, and claims it was built in 1869 for P. McGonigle & Son,

who began

distilling 18 barrels a day there in 1870. In 1875, the distillery was sold to Asher Guckenheimer, Samuel Wertheimer, Emil Wertheimer and Isaac

Wertheimer.

The

Brown history also states that this distillery was operated as the

Pennsylvania Distilling Company, and continued to be so after the

sale. And also that it burnt to the ground in July of 1883, being

immediately replaced with a much larger plant, built on the same site. The

new distillery, with a 50-gallon per day capacity, was in operation when

the history was published in 1895.

The

Brown history also states that this distillery was operated as the

Pennsylvania Distilling Company, and continued to be so after the

sale. And also that it burnt to the ground in July of 1883, being

immediately replaced with a much larger plant, built on the same site. The

new distillery, with a 50-gallon per day capacity, was in operation when

the history was published in 1895.

Pretty impressive, except that we were unable to find a reference to P. McGonigle & Son in

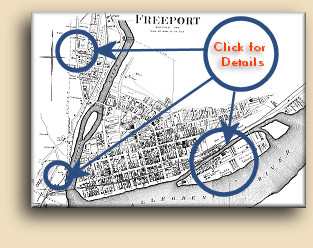

any of the other published histories. But this map,

drawn in 1876, clearly shows, at the location described, a site labeled,

Distillery - McGonegly & Helmbold. We believe the name

McGonegly is likely

a corruption of McGonegal. We've discovered several such

corruptions in historic accounts, including some others we'll mention here

later.

The Brown history also fails to mention Guckenheimer's

proud accomplishment at the 1893 Columbian Exposition (even though that would have been a recent

event in 1895). One might explain that omission as a result of the history,

being oriented, as it was, on

Butler, not Armstrong, county, and focusing only on their relationship with the

local distillery. However, they also make no reference to the

Montrose brand, which the Gazette-Times and the Snyder database indicate was the major, and perhaps the only, brand of whiskey distilled

there.

indicate was the major, and perhaps the only, brand of whiskey distilled

there.

Or at least that was true of McGonegal, Helmbold & Co.

But then we received a letter from J. Scott Bevan about a year and a half ago, confirming his belief that the original distillery was, indeed, the P. McGonigle & Son distillery, located on the Butler county side of Buffalo Creek. He also confirmed that it was destroyed by fire and re-built. However, Scott placed the distillery, not directly across the creek from Freeport, but in Laneville, which is north of that area. Part of Laneville lies in Armstrong county, and part in Butler. The map, which is focused on Buffalo Township, doesn't show much detail beyond the Butler county line, so we can't determine from that whether a distillery existed here as well. But if both Scott and the Brown history are correct, then P. McGonigle & Son may have been a separate enterprise from McGonegal, Helmbold & Co. Then again, perhaps Mr. Bevan's information was taken from the Brown history.

But if there were, indeed, two similarly-named distilleries,

might not Guckenheimer have been involved with both of them? Like the

Brown history, Bevan doesn't mention the Montrose brand; perhaps

P.

McGonigle & Son produced Fairy Breath or Pennbrook?

Perhaps

both were distilleries owned by Pennsylvania Distilling Company and

were acquired by Guckenheimer as part of the same transaction?

Perhaps

both were distilleries owned by Pennsylvania Distilling Company and

were acquired by Guckenheimer as part of the same transaction?

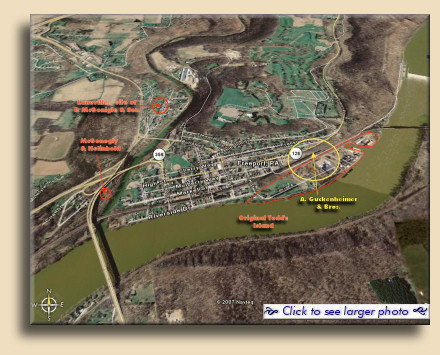

The map also shows references to a much larger distillery on Todd's Island

in the Allegheny River, but does not totally identify it. There are

properties labeled "A.G. & Bros" on the 1876 map, which we feel pretty

certain refers to Guckenheimer, but we see none in the area where those

distillery buildings are shown. There is writing obscured by the pattern

in the channel area, but enough can be seen to eliminate it's being

"Guckenheimer". Nevertheless, we can see that there certainly was a

large distillery here, and we believe that was (at least for awhile) the

site of the A. Guckenheimer & Bros. distillery.

The reason we bring all this up is that there are more

inconsistencies among the various histories, some of which cannot be so

easily dismissed as the spelling or pronunciation of a name (although

there's more of that, too).

Now, according to Robert Walker Smith, author of The History of Armstrong

County (Waterman, Watkins & Co. - Chicago), published in 1883

(available online through the

Armstrong County Pennsylvania Genealogy Project (PAGenWeb), one of

Freeport's original founders, Jacob Weaver, was operating a distillery in

Freeport as early as 1811.

The

county tax assessment list for 1818 shows a distillery in Freeport

belonging to Henry S. Weaver, but does not provide a location. The 1876

map shows a large tract adjacent to the distillery area that is owned by a

P. S. Weaver. Could Henry Weaver's property have been where the distillery

buildings are shown?

The

county tax assessment list for 1818 shows a distillery in Freeport

belonging to Henry S. Weaver, but does not provide a location. The 1876

map shows a large tract adjacent to the distillery area that is owned by a

P. S. Weaver. Could Henry Weaver's property have been where the distillery

buildings are shown?

Smith, however, claims that the Guckenheimer Brothers

purchased their distillery, not from Henry Weaver but from the Williamson & Rhey Company, who began

distilling there in 1855. In Smith's history, Guckenheimer purchased the

distillery from them in 1866. There is no mention in this history of a

Thomas Bell, nor of his death, nor of any distillery operating in Butler

county in the 1840s.

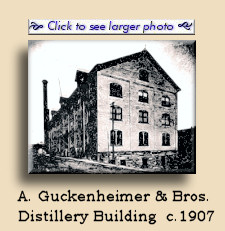

The A. Guckenheimer & Bros. Company (and perhaps the Williamson & Rhey

Company before it) was no small operation, either, according to the Robert

Smith history. In 1876, there were all of 357 employed persons living in

Freeport, of which 25 worked for the distillery. The facilities included a

3-story brick distillery building, a grain-house holding 30,000 bushels, a

150-ton capacity ice-house, a 3-story brick malt-house capable of malting

100 bushels per day, a 50-barrel/day cooper-shop, and a 3-story brick

bonded warehouse with a capacity of 8,000 barrels. They normally operated

at 50% of their 500 bushels/day capacity, producing 22 42-gallon barrels a

day. Smith also notes that they supported 100 cattle and 500 hogs on daily

slop production.

The

size of the main distillery building leads us to believe they did not

operate a continuous (column-type) still at that time, since these

typically require a taller structure, although it would be possible if the

first story were a basement.

The

size of the main distillery building leads us to believe they did not

operate a continuous (column-type) still at that time, since these

typically require a taller structure, although it would be possible if the

first story were a basement.

Interestingly, the Gazette-Times article, in their description of the large, modern facility built immediately after purchasing the smaller one, also portrays a state-of-the-art plant, a model for modern distilling in mid-19th century America. The distillery they describe, however, is much larger. In addition to the steel and brick distillery building and brick malt house, they write of a grain elevator (of "approved Chicago construction") with a capacity ten times that of the one that so impressed Robert Smith. The realized production capacity was 100 barrels every ten-hour shift, as opposed to the former article's 22 barrels a day, and they were capable of doubling that output. In the Gazette-Times article, in place of the 8,000-barrel brick warehouse mentioned by Smith, we find no less than seven bonded warehouses with a combined capacity of over 200,000 barrels. Despite a brisk commercial trade (whiskey was still often wholesaled by the barrel then), as of 1908 they were bottling from fifty to ninety barrels of whiskey a day, and employing between 75 and 100 bottlers. That's a far cry from the 25 employees "in all departments" reported by Robert Smith.

J. H. Beers & Co., in their definitive history of Armstrong

County, Pa., "Her

People, Past and Present" Volume I, published in 1914 confirms all of

the above, except that they show an additional two warehouses and a total

employee payroll of 125.

Clearly, these histories are not describing the same distillery. And Freeport was never big enough to have supported two such operations.

So where were they?

With all of its attention to detail (spanning several

paragraphs in the original article) the Gazette-Times is quite vague about

the actual location, saying only that the site, covering over thirty-five

acres by the way, was somewhere "near Freeport, in the Allegheny Valley".

Considering that the distillery we most tend to associate with

Guckenheimer was located, not "near Freeport", but smack in the

middle of it, occupying most of the town by at least 1876, and would only

have grown larger by 1908 when "The Story of Pittsburgh" was published, it

leads us to wonder if the article may have been referring to a completely

different distillery.

By 1908, Guckenheimer either was, or was associated

with, the Pennsylvania Distilling Company, of Logansport, which was an

Allegheny Valley community just a few miles up the river from Freeport. And,

while the post-prohibition Guckenheimer whiskeys made by American

Distillers in Illinois referred proudly to its 1857 origin in Freeport,

the whiskey sold by Asher Guckenheimer & Bros. said only "Pittsburgh,

Penna." on the label, that being where the Guckenheimer's business was

located. Since the Gazette-Times article is clearly supportive of the

company, to the point of reading almost like an investors' prospectus (or

the narrative to a late-night infomercial), one can assume that it had the

official sanction of the company. And one should also allow for some

hyperbole in the descriptions. Still, it remains very intriguing.

By 1908, Guckenheimer either was, or was associated

with, the Pennsylvania Distilling Company, of Logansport, which was an

Allegheny Valley community just a few miles up the river from Freeport. And,

while the post-prohibition Guckenheimer whiskeys made by American

Distillers in Illinois referred proudly to its 1857 origin in Freeport,

the whiskey sold by Asher Guckenheimer & Bros. said only "Pittsburgh,

Penna." on the label, that being where the Guckenheimer's business was

located. Since the Gazette-Times article is clearly supportive of the

company, to the point of reading almost like an investors' prospectus (or

the narrative to a late-night infomercial), one can assume that it had the

official sanction of the company. And one should also allow for some

hyperbole in the descriptions. Still, it remains very intriguing.

As for Smith's version, well... we can't find any

other reference at all that corroborates the existence of the Williamson & Rhey

Company in any other documents. But the

name Rhey does occur in connection with yet another Freeport distillery,

oddly enough in Smith's same work...

In a separate section concerning

land sales and title transfers, Smith notes the purchase, by A. V. McKim,

of a parcel (106¾ perches) of

[tract] No. 1 (part of what was then Todd's Island), on which a distillery

had been built in 1858 by John Moyer. There was apparently some conflict

over the

title, as the property seems to have been the same, according to Smith,

as a parcel "... with which Rhey and Bell were assessed in 1859...".

Smith then goes on to say that the title conflict was resolved by

John S. Bole and

Thomas Magill purchasing McKim's interest in January of

1866.

And wouldn't you know, that's the same year that Smith places the purchase by Guckenheimer of the "Williamson & Rhey" distillery.

Look at the map again, and you'll see a very large, but

unnamed, distillery compound, shown with unusual, building-by-building

detail, located in the exact area described in this section. The map's

listings of property owners also shows plainly that J. S. Bole and T.

McGill (Magill) are already major holders of land here.

In December of 2003, Ryan Kennedy wrote to us about his

great-great-great grandfather, John T. Kennedy who lived in Freeport with his

family at that time. Their home was on Todd's Island, and can be seen on

the 1876 Freeport map, adjacent to T. McGill's property and the Freeport

Woolen Mills. In 1879 they left Freeport and sold the property to

Guckenheimer Bros., which Ryan confirms was indeed the group of distillery

buildings directly across the channel. That channel is no longer there, by

the way, so what was once Todd's "Island" is no longer separated from the old shoreline.

The distillery existed pretty much where we had expected it be, although

there is no trace of its existence today, nor much of anything else. We were, in fact, parked on the site

when we asked and were given directions to the Schenley distillery by a

local citizen.

So, was Rhey (otherwise unidentified) the "Rhey" of "Williamson & Rhey"?

And, if so, then was Bell (also otherwise unidentified) "Thomas Bell", the distiller?

Or

was Thomas Bell really the owner (perhaps along with Rhey) of another,

completely different

property erroneously identified as the Moyer

Distillery in the county tax assessment?

And was the reference to "Thomas Bell" in the Pittsburgh

Gazette-Times (and subsequently in the Snyder database) the result of

confusing the name "Thomas Bell" (who might still be listed as the owner in

some records) and the actual

owners "Thomas McGill" and "John Bole?" It doesn't take a difficult stretch of

imagination to see the potential for corrupting "Thomas" McGill and John

"Bole" into "Thomas Bole" (or "Bell"). That would make

about as much sense as everything else we've learned.

This old postcard shows Freeport in the early 1900s. Todd's Island and the

channel are easy to discern, the woolen mills and A. G. & Bros' pig lot,

as shown on the 1876 map can be located for reference. Thus, the group of

very large buildings on both sides of the channel between the rest of the

town and the island would have to

be the Guckenheimer Bros Distillery.

Or somebody's.

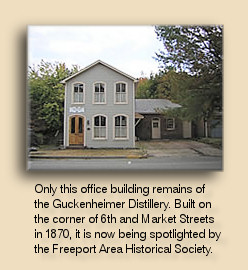

In J. Scott Bevan's letter, he writes of two warehouses on the north side of Market Street, between Fifth and Sixth, as well as a couple other buildings from the distillery still standing.

That was in 1981.

Those buildings would have been empty for a long, long time by then.

In 1920, when the Volstead Act went into effect, literally hundreds of distilleries, large and small, were suddenly left with nothing of value except their scrap copper and their brand names. And for both of those there were scavengers offering to buy up everything available at pennies on the dollar. Great, gleaming copper stills got melted down and reused for other things. Brand names got "melted down and reused", too, sort of. They were accumulated and used to label medicinal whiskey. Or just bought and sold by speculators who believed that prohibition wouldn't work out and would be repealed.

Silly

speculators! What do THEY know?

Thirteen years later, prohibition became the only Constitutional Amendment

ever to be repealed. And along with it went the Volstead Act. Silly

speculators became industry leaders overnight. The Pennsylvania Distilling Company,

now owned by Irwin and Morris Weiner and located in Logansport,

re-established some of its brands, including Guckenheimer. For awhile, it might have been

Guckenheimer whiskey from their own warehouses being bottled under their

name, but even that

eventually ran out.

As did the relationship between the Weiner brothers. This we learned in

correspondence a couple years ago with Hilary Weiner Elliot, daughter of

Irwin Weiner. She remembers that nearly the whole town of Logansport was

employed by the Pennsylvania Distilling Company at that time. Unable to reconcile

their differences, Irwin and Morris dissolved their partnership in 1940 or

'41 and sold

the company. Ms. Elliot believes it was sold either

to Schenley or to National Distillers, she wasn't sure which. Actually, it

was probably to Adolph Hirsch (of A. H. Hirsch & Michter's fame) and his

partners who are known to have purchased the Pennsylvania Distilling

Company at around that time, changing its name to the Logansport

Distilling Company. It's interesting to speculate whether any relationship

might exist between Michter's whiskey and whiskey produced by

Guckenheimer.

Ms. Elliot believes it was sold either

to Schenley or to National Distillers, she wasn't sure which. Actually, it

was probably to Adolph Hirsch (of A. H. Hirsch & Michter's fame) and his

partners who are known to have purchased the Pennsylvania Distilling

Company at around that time, changing its name to the Logansport

Distilling Company. It's interesting to speculate whether any relationship

might exist between Michter's whiskey and whiskey produced by

Guckenheimer.

At any rate, by the end of the forties, the Pennsylvania

Distilling Company was sold to Schenley. The Guckenheimer brand itself was eventually sold

to the American Distilling Company in Pekin, Illinois. They used it for

several years, along

with it's trademark "Good Old Guckenheimer" slogan, to market a straight

bourbon whiskey which they made for awhile

(quite an insult for a brand once considered

to be among America's premier rye whiskeys) in Illinois,

then bottled using commercial-grade bourbon from Kentucky, and then they

even further degraded it to a blended whiskey. American Distilling itself

eventually pooped out, its brands being acquired by Heaven Hill in

Bardstown, Kentucky. "Good

Old Guckenheimer" remains available today as an 80º

proof blended whiskey, and may be found on the bottom

shelf of liquor stores in some areas.

(quite an insult for a brand once considered

to be among America's premier rye whiskeys) in Illinois,

then bottled using commercial-grade bourbon from Kentucky, and then they

even further degraded it to a blended whiskey. American Distilling itself

eventually pooped out, its brands being acquired by Heaven Hill in

Bardstown, Kentucky. "Good

Old Guckenheimer" remains available today as an 80º

proof blended whiskey, and may be found on the bottom

shelf of liquor stores in some areas.

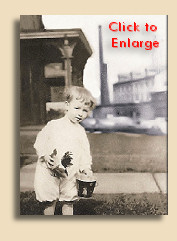

This year we received an email from Bud Skinner, who went through a lot of trouble to contact us. Bud wanted to share with us a photograph of his father, as a very young child, taken in front of his family's Freeport home. In the background can be seen the smokestack and distillery building of A. Guckenheimer & Bros. as it was in about 1915. We love this picture. In many ways, it says what it is that we love so much about our obsession with American whiskey. It's really not about alcohol, or nation-building, or connoisseur-ship, or whether they just don't make 'em like they used 'ter anymore, even though it's about all of those things. It's about how, nearly a hundred years ago, a kid just like me loved his pail and favorite elf figure so much that he'd even agree to endure getting his picture taken as long as he could have them around.

Oh... and yeah, there was a distillery there, too.

Also, J. Scott Bevan related a couple a word-pictures you might

enjoy as much as we did...

|

" ... wanted to pass along a little information on the Guckenheimer Distillery [and] a gentleman named Herman Sarver (he was about 103 years old when he died a few years ago)." |

Note: the Sarver

family are among the very first settlers in the region. The nearby town of

Sarverville is named for them and they figure in many of the communities in

the area, including Freeport. Bevan goes on to say...

|

"I

worked bailing hay for Ol’ Herman as a boy and even raided his corn fields

for corn-on-the-cob campfires (work by day, raid by night)

Ol' Herm’s farm located in South Buffalo Twp on Sunset Drive had raised

corn, rye, alfalfa for feed for a number of years but as kids growing up we

had heard and knew Herm had at one time (and still did) raised corn and rye

(sold direct) for whiskey being distilled at the Schenley Distillery (Jos.

Finch and Sons) in Schenley, PA. Many an hour was spent looking for

bottles of booze in his out buildings. I even remember seeing a

“line-up” of dusty, cobwebbed bottles sitting on a window sash having been

long ago drunk and “cooked” off by the suns rays streaming through the

window. Tobacco juice colored remnants of that prized syrupy liquor

huddled in the corners of those bottles. Alas, if only it could have been

reconstituted. One of those bottles was definitely a

Guckenheimer (I called it Guggenheim ala Jackie Gleason’s Crazy Guggenheim).

A story was told that every other year a barrel of Schenley Whiskey was

delivered to Herm Sarver’s home as something Schenley just did..." | |

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2006 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|