|

The Wight Stuff

ONE OF MARYLAND's best-known rye distilleries,

with expressions popular both before and after the prohibition years, was the

Sherwood brand. And, as often happened with other old Maryland brands, prohibition found a

strong family continuity in the distilling industry traveling a different

road from the brand name with which it was once associated.

And, as often happened with other old Maryland brands, prohibition found a

strong family continuity in the distilling industry traveling a different

road from the brand name with which it was once associated.

The town of Cockeysville lies about seventeen miles north of Baltimore on the

road that goes to York, Pennsylvania. People from outside

of the area are more likely to know it as Hunt Valley, but

that name was invented out of nowhere by real estate speculators in the 1960s.

Two hundred years earlier, the buffalo and the Shawnee tribes who hunted them

gradually gave the area up to white settlers, among whom were the Cockey family,

who built a hotel and convinced the Baltimore & Susquehanna railroad to

establish a station here.

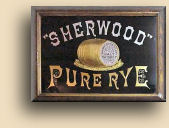

Among

the industries taking advantage of the railroad by the late 19th century was a

distillery operated by William Lentz and John J. Wight. As best as we can figure

out, the distillery was located in the area now occupied by Procter & Gamble's

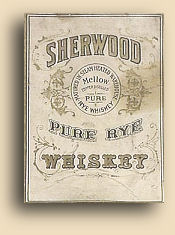

Noxell plant. Their product was named Sherwood Pure Rye, after a nearby church. Among

the industries taking advantage of the railroad by the late 19th century was a

distillery operated by William Lentz and John J. Wight. As best as we can figure

out, the distillery was located in the area now occupied by Procter & Gamble's

Noxell plant. Their product was named Sherwood Pure Rye, after a nearby church.

Meanwhile, Baltimore grocer Al Hyatt's son Edward and his partner

Nicholas Griffith operated a whiskey dealership (Griffith & Hyatt) until 1863,

when Hyatt moved to New York and teamed up with a gentleman named Clark.

By 1868

Hyatt & Clark were able to purchase the Wight distillery in Cockeysville and

enlarge it to allow broad-scale producing and marketing of their own brand-name

Maryland Rye whiskey. Within ten years the Army’s Medical Purveying Depot in New

York was stockpiling Sherwood Rye Whiskey for hospital use. In 1882, after Hyatt

& Clark dissolved, Hyatt incorporated the firm as The Sherwood Distilling Co.,

with himself as president. The relationship between the Hyatts and the Wights

must have been a pretty close one as well, for after Hyatt’s death in 1894,

company leadership was taken over by John Hyatt Wight. By 1868

Hyatt & Clark were able to purchase the Wight distillery in Cockeysville and

enlarge it to allow broad-scale producing and marketing of their own brand-name

Maryland Rye whiskey. Within ten years the Army’s Medical Purveying Depot in New

York was stockpiling Sherwood Rye Whiskey for hospital use. In 1882, after Hyatt

& Clark dissolved, Hyatt incorporated the firm as The Sherwood Distilling Co.,

with himself as president. The relationship between the Hyatts and the Wights

must have been a pretty close one as well, for after Hyatt’s death in 1894,

company leadership was taken over by John Hyatt Wight.

As early as 1914, Frank L. Wight was working at the distillery, and he

continued to do so right up to the day it closed down in compliance with

national prohibition.

With

passage of the 21st Amendment he went on to become a major figure in Maryland's

post-Repeal distilling industry. With

passage of the 21st Amendment he went on to become a major figure in Maryland's

post-Repeal distilling industry.

But not with the Sherwood brand.

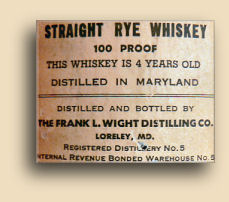

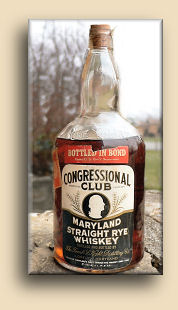

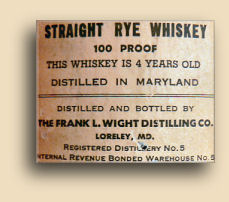

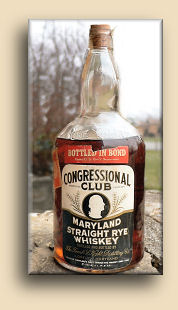

He headed the Frank L. Wight Distilling Co., which built a

distillery at Loreley, in the Whitemarsh area further toward the east side of

Baltimore, and marketed Sherbrook, Wight's Old Reserve, and Congressional Club

Maryland straight ryes.

That

distillery was purchased by the Hiram Walker, Inc. of Canada and subsequently

shut down when production moved to their Peoria, Illinois facility (see photo of

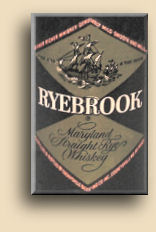

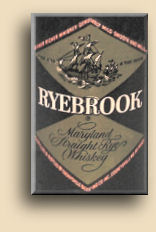

label). Whereupon, Wight organized the Cockeysville Distilling Company and in

1946 he built

a distillery just down the street from where the original Sherwood site had

stood until the buildings were demolished in 1926. Unable to

regain access to the Sherwood brand, Wight produced and marketed instead a

Maryland straight rye he called Ryebrook. That

distillery was purchased by the Hiram Walker, Inc. of Canada and subsequently

shut down when production moved to their Peoria, Illinois facility (see photo of

label). Whereupon, Wight organized the Cockeysville Distilling Company and in

1946 he built

a distillery just down the street from where the original Sherwood site had

stood until the buildings were demolished in 1926. Unable to

regain access to the Sherwood brand, Wight produced and marketed instead a

Maryland straight rye he called Ryebrook.

Wight's principal backer was Heublein, Inc., of Connecticut, and

following Wight's death in 1958 they shut down the distillery.

Altogether four generations of Wights distilled whiskey in

Maryland, the last being John Hyatt Wight II, who died in 1990 at the age of

seventy-eight.

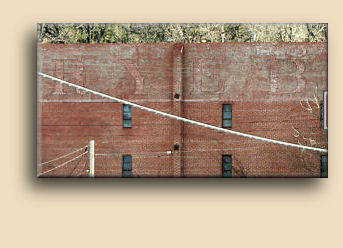

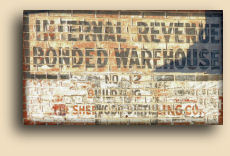

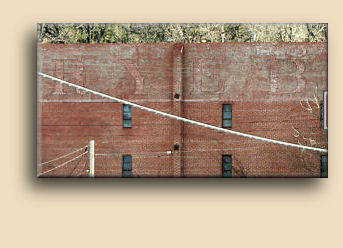

Portions of the Cockeysville distillery still remain.

A

brick warehouse on York Road, still wears the word, "Home of RYEBROOK" in faded

paint along its roofline.. Even more clear are the words "COCKEYSVILLE

DISTILLING COMPANY" inlaid on the front of the building, although partially

obscured by a banner for an appliance repair shop. The warehouse and another

building are now used as a

small industrial compound containing a cafe, the appliance repair, and Mark

Downs Furniture, a discount and second-hand store with the cleverest name we've

seen in a long while (John says he can visualize the late-night TV commercial,

with the proprietor himself A

brick warehouse on York Road, still wears the word, "Home of RYEBROOK" in faded

paint along its roofline.. Even more clear are the words "COCKEYSVILLE

DISTILLING COMPANY" inlaid on the front of the building, although partially

obscured by a banner for an appliance repair shop. The warehouse and another

building are now used as a

small industrial compound containing a cafe, the appliance repair, and Mark

Downs Furniture, a discount and second-hand store with the cleverest name we've

seen in a long while (John says he can visualize the late-night TV commercial,

with the proprietor himself -- faithful dog at his side -- saying, ".. .best deal in the Tri-State. I'm Mark

Downs, and you have my word on it!").

-- faithful dog at his side -- saying, ".. .best deal in the Tri-State. I'm Mark

Downs, and you have my word on it!").

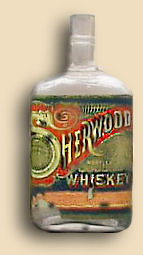

The Ryebrook brand is a name that is virtually non-existent in

internet searches. The only example we've found is this label, shown here

courtesy of

John Sullivan's wonderful

collection of miniatures. John specializes in miniature vodka bottles, but

that doesn't prevent him from supporting an impressive display of American whiskey minis as well (not unlike

our own "non-collection" of rum or beer bottles).

impressive display of American whiskey minis as well (not unlike

our own "non-collection" of rum or beer bottles).

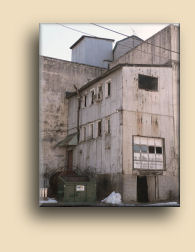

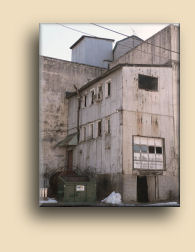

Standing next to the warehouse, and part of the same complex, is

another rambling building, even larger than the warehouse. It has no old

markings or signage, but it appears to be contemporary with the other building,

if not a bit older. The furniture store is actually a separate, more modern

structure behind, and across a small creek, from these two.

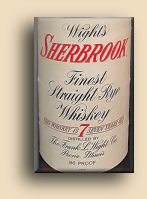

Heublein also marketed "Wight's Sherbrook Straight Rye

Whiskey", which they produced at their giant facility in Peoria, Illinois.

That

brand name may seem to have been chosen in order to take advantage of customer

confusion, as that was a common practice among Maryland whiskey merchants, but

actually there really had been a "Sherbrook" brand before prohibition, albeit not in

Maryland. That

brand name may seem to have been chosen in order to take advantage of customer

confusion, as that was a common practice among Maryland whiskey merchants, but

actually there really had been a "Sherbrook" brand before prohibition, albeit not in

Maryland.

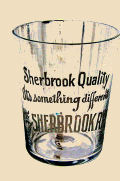

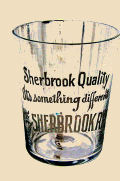

The

Sherbrook Distillery which operated in Cincinnati from 1900 to 1918 was a very

large company. The Robert E. Snyder Whiskey Brand Database lists no less than

forty-five different brands registered to Sherbrook, with names that

indicated at least national, if not worldwide, distribution. Such a

well-recognized name would have been advantageous even without the similarity to

Sherwood. The shot glass seen here was distributed as a promotional piece

for the Cincinnati Sherbrook. The

Sherbrook Distillery which operated in Cincinnati from 1900 to 1918 was a very

large company. The Robert E. Snyder Whiskey Brand Database lists no less than

forty-five different brands registered to Sherbrook, with names that

indicated at least national, if not worldwide, distribution. Such a

well-recognized name would have been advantageous even without the similarity to

Sherwood. The shot glass seen here was distributed as a promotional piece

for the Cincinnati Sherbrook.

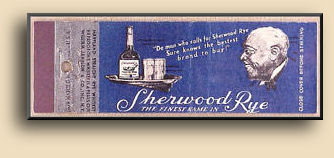

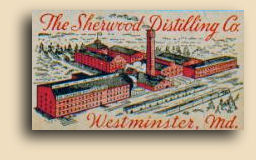

Meanwhile, the Sherwood brand didn't entirely disappear. During

prohibition, Sherwood Rye was sold as prescription medicine and eventually the

brand was purchased by Louis Mann.

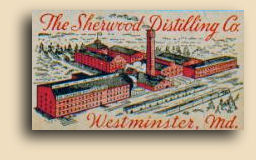

His

Sherwood Distilling Company was located, at least nominally, in Westminster,

about 25 miles northeast of Cockeysville. Much of the bottling, however (and

perhaps distilling as well), was done at the William Foust Distillery, twenty

miles further north in Glen Rock,

Pennsylvania. Mann built The Sherwood Distilling Corporation into the fourth

most important independent distilling company in America His

Sherwood Distilling Company was located, at least nominally, in Westminster,

about 25 miles northeast of Cockeysville. Much of the bottling, however (and

perhaps distilling as well), was done at the William Foust Distillery, twenty

miles further north in Glen Rock,

Pennsylvania. Mann built The Sherwood Distilling Corporation into the fourth

most important independent distilling company in America

According to journalist James H. Bready, writing for the Maryland

Historical Society, some of the early (Hyatt & Clark) Sherwood Rye was shipped

to Cuba and back as part of its aging process, a smaller-scale implementation of

the "grand tour" method being used by Outerbridge Horsey. Interestingly, that's

not the only connection we've discovered between these two brands.

The

post-Repeal Sherwood Distilling Company (of Westminster) bottled whiskey under

the name Old Horsey Rye in Glen Rock at the Foust Distillery. The

post-Repeal Sherwood Distilling Company (of Westminster) bottled whiskey under

the name Old Horsey Rye in Glen Rock at the Foust Distillery.

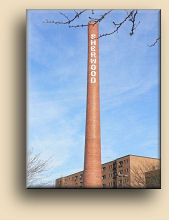

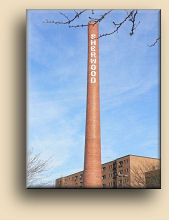

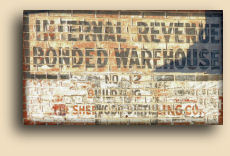

There are also remnants of the World War II era Sherwood Distillery in

Westminster, with an interesting twist. One of the structures was a building

with large glass windows constructed during World War II to serve as a

mash-drying house producing feed for cattle from the mash used in the whiskey

production. Known

locally as "The Glass House" and considered a community eyesore, it remained

neglected for decades, crumbling slowly into oblivion along with its surrounding

neighborhood. During the 1990's the area became included in Westminster's

Priority Funding Area, funded partially from Maryland's Neighborhood Development

Loan Program and the Carroll County Small Business Development Center, and

this building, along with its adjoining brick smokestack, was among the projects

receiving extensive repair and restoration. It opened as the Paradiso Italian

Restaurant in 1998 and is now one of the city's most popular destinations.

John

visited the restaurant in February 2006, enjoying a delicious and beautifully

prepared dinner in the classic, elegant atmosphere they've created. John

discovers a certain bittersweet irony, however. John

visited the restaurant in February 2006, enjoying a delicious and beautifully

prepared dinner in the classic, elegant atmosphere they've created. John

discovers a certain bittersweet irony, however.

Although the staff is well aware

of the history of the building, and the tasteful decor includes a

prominently-displayed bottle of Sherwood Pure Rye Whiskey, the bar (and why

couldn't this have been more of a surprise?) does not stock any rye whiskey at

all, and the bartender isn't even sure he'd ever tasted any. Although the staff is well aware

of the history of the building, and the tasteful decor includes a

prominently-displayed bottle of Sherwood Pure Rye Whiskey, the bar (and why

couldn't this have been more of a surprise?) does not stock any rye whiskey at

all, and the bartender isn't even sure he'd ever tasted any.

|

And, as often happened with other old Maryland brands, prohibition found a

strong family continuity in the distilling industry traveling a different

road from the brand name with which it was once associated.

And, as often happened with other old Maryland brands, prohibition found a

strong family continuity in the distilling industry traveling a different

road from the brand name with which it was once associated. Among

the industries taking advantage of the railroad by the late 19th century was a

distillery operated by William Lentz and John J. Wight. As best as we can figure

out, the distillery was located in the area now occupied by Procter & Gamble's

Noxell plant. Their product was named Sherwood Pure Rye, after a nearby church.

Among

the industries taking advantage of the railroad by the late 19th century was a

distillery operated by William Lentz and John J. Wight. As best as we can figure

out, the distillery was located in the area now occupied by Procter & Gamble's

Noxell plant. Their product was named Sherwood Pure Rye, after a nearby church. By 1868

Hyatt & Clark were able to purchase the Wight distillery in Cockeysville and

enlarge it to allow broad-scale producing and marketing of their own brand-name

Maryland Rye whiskey. Within ten years the Army’s Medical Purveying Depot in New

York was stockpiling Sherwood Rye Whiskey for hospital use. In 1882, after Hyatt

& Clark dissolved, Hyatt incorporated the firm as The Sherwood Distilling Co.,

with himself as president. The relationship between the Hyatts and the Wights

must have been a pretty close one as well, for after Hyatt’s death in 1894,

company leadership was taken over by John Hyatt Wight.

By 1868

Hyatt & Clark were able to purchase the Wight distillery in Cockeysville and

enlarge it to allow broad-scale producing and marketing of their own brand-name

Maryland Rye whiskey. Within ten years the Army’s Medical Purveying Depot in New

York was stockpiling Sherwood Rye Whiskey for hospital use. In 1882, after Hyatt

& Clark dissolved, Hyatt incorporated the firm as The Sherwood Distilling Co.,

with himself as president. The relationship between the Hyatts and the Wights

must have been a pretty close one as well, for after Hyatt’s death in 1894,

company leadership was taken over by John Hyatt Wight.  With

passage of the 21st Amendment he went on to become a major figure in Maryland's

post-Repeal distilling industry.

With

passage of the 21st Amendment he went on to become a major figure in Maryland's

post-Repeal distilling industry.  That

distillery was purchased by the Hiram Walker, Inc. of Canada and subsequently

shut down when production moved to their Peoria, Illinois facility (see photo of

label). Whereupon, Wight organized the Cockeysville Distilling Company and in

1946 he built

a distillery just down the street from where the original Sherwood site had

stood until the buildings were demolished in 1926. Unable to

regain access to the Sherwood brand, Wight produced and marketed instead a

Maryland straight rye he called Ryebrook.

That

distillery was purchased by the Hiram Walker, Inc. of Canada and subsequently

shut down when production moved to their Peoria, Illinois facility (see photo of

label). Whereupon, Wight organized the Cockeysville Distilling Company and in

1946 he built

a distillery just down the street from where the original Sherwood site had

stood until the buildings were demolished in 1926. Unable to

regain access to the Sherwood brand, Wight produced and marketed instead a

Maryland straight rye he called Ryebrook.

-- faithful dog at his side -- saying, ".. .best deal in the Tri-State. I'm Mark

Downs, and you have my word on it!").

-- faithful dog at his side -- saying, ".. .best deal in the Tri-State. I'm Mark

Downs, and you have my word on it!").

That

brand name may seem to have been chosen in order to take advantage of customer

confusion, as that was a common practice among Maryland whiskey merchants, but

actually there really had been a "Sherbrook" brand before prohibition, albeit not in

Maryland.

That

brand name may seem to have been chosen in order to take advantage of customer

confusion, as that was a common practice among Maryland whiskey merchants, but

actually there really had been a "Sherbrook" brand before prohibition, albeit not in

Maryland.

The

Sherbrook Distillery which operated in Cincinnati from 1900 to 1918 was a very

large company. The Robert E. Snyder Whiskey Brand Database lists no less than

forty-five different brands registered to Sherbrook, with names that

indicated at least national, if not worldwide, distribution. Such a

well-recognized name would have been advantageous even without the similarity to

Sherwood. The shot glass seen here was distributed as a promotional piece

for the Cincinnati Sherbrook.

The

Sherbrook Distillery which operated in Cincinnati from 1900 to 1918 was a very

large company. The Robert E. Snyder Whiskey Brand Database lists no less than

forty-five different brands registered to Sherbrook, with names that

indicated at least national, if not worldwide, distribution. Such a

well-recognized name would have been advantageous even without the similarity to

Sherwood. The shot glass seen here was distributed as a promotional piece

for the Cincinnati Sherbrook. His

Sherwood Distilling Company was located, at least nominally, in Westminster,

about 25 miles northeast of Cockeysville. Much of the bottling, however (and

perhaps distilling as well), was done at the William Foust Distillery, twenty

miles further north in Glen Rock,

Pennsylvania. Mann built The Sherwood Distilling Corporation into the fourth

most important independent distilling company in America

His

Sherwood Distilling Company was located, at least nominally, in Westminster,

about 25 miles northeast of Cockeysville. Much of the bottling, however (and

perhaps distilling as well), was done at the William Foust Distillery, twenty

miles further north in Glen Rock,

Pennsylvania. Mann built The Sherwood Distilling Corporation into the fourth

most important independent distilling company in America

John

visited the restaurant in February 2006, enjoying a delicious and beautifully

prepared dinner in the classic, elegant atmosphere they've created. John

discovers a certain bittersweet irony, however.

John

visited the restaurant in February 2006, enjoying a delicious and beautifully

prepared dinner in the classic, elegant atmosphere they've created. John

discovers a certain bittersweet irony, however.