| American

Whiskey

September 29, 2004 Yes, Virginia, there is a Gentleman

|

||||||

Myth: By law,

bourbon whiskey can only be made in Kentucky

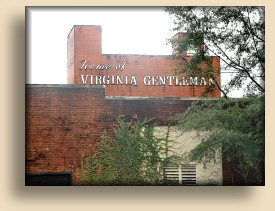

You see, here in the Old Dominion, on the bank of the Rappahannock, true bourbon whiskey is being distilled, aged, and bottled. It’s known as Virginia Gentleman. In fact, it’s well-known indeed. For decades it’s been a very popular bourbon. And it’s red and white label is quite familiar in northern Virginia. And southern Maryland. And Washington, D.C. Yes, THAT Washington, D.C. So that means that congressmen and

senators and people of influence (even presidents?) are familiar with this

bourbon. For foreign ambassadors and distinguished guests of our country who

may have tasted only one bourbon in their lives, Virginia Gentleman could

well have been that bourbon.

It was never the best bourbon ever made, but it was always quite acceptable. Just a good bourbon whiskey. And about half a dozen years ago they released a more carefully-crafted 90-proof (45%ABV) premium version, known as The Fox because of the custom bottle with a fox's head molded into the glass and a painting of a fox hunt on the label. This one’s more than just a good bourbon whiskey. It’s an award-winning bourbon whiskey. And rightfully so. If you are already familiar with the lighter forms of premium bourbons, such as Maker’s Mark, you’ll be very impressed with the premium Virginia Gentleman. Even many of those who normally prefer more robust bourbon flavor find it within their comfort range. F. Paul Pacult’s Spirit Journal found it comfortable enough to give it four stars. In both 2000 and 2001 it came home

from the San Francisco World Spirits Competition with silver medals. And they don't make it from corn. Or rye. Or wheat. Or barley. They make it from distilled spirits that cannot legally even be called

whiskey. Confused? Well that’s understandable. Welcome to the wacky world of federal standards and legal alcohol beverage definitions. There is a document, produced and kept updated periodically by the United States Treasury’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, which includes the exact legal definition of straight bourbon whiskey (and rye, vodka, tequila, imitation blueberry brandy, scotch, and everything else involving beverage spirits). Affectionately known as Title 27, Chapter 1, Subpart C, Section 5.22 of the Code of Federal Regulations, pages 48-53, this document includes the basis for that little factoid we opened this article with. So now you can win some bar room bets, provided you’re brawny enough to get away with it. Oh, and it also includes the legal definition of “bourbon”:

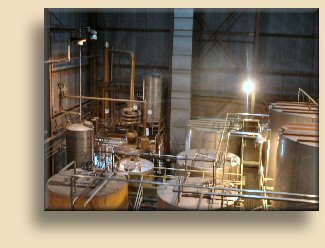

… etc. and so on (emphasis added). Master Distiller Joe Dangler doesn’t

mash grain to make his bourbon. The distillery contains no grain storage or

milling machinery, no giant cypress fermenting vats, no carefully maintained

dona tanks of proprietary yeast cultures. Among the equipment it does

contain

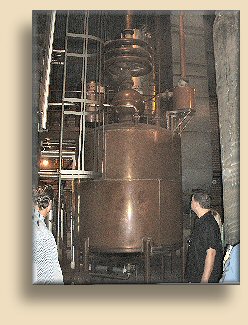

And a huge pot still it is, too. Not onion-shaped, the way stills are made in Scotland or Ireland (or Versailles, Kentucky). This pot still looks like it was designed by Gene Roddenberry for Star Trek. Or maybe even Willie Wonka's Chocolate Factory. That’s because it wasn’t designed by a well-known designer of distilling apparatus, it was designed by John B. “Jay” Adams, whose distillery this is. Jay Adams is, in fact, the President and CEO of A. Smith Bowman, although that position has recently been superceded as a result of their acquisition by Sazerac Corporation. But far beyond the meaning of the title, this distillery, and the way of life it represents, is a creation of this remarkable person, whose essence can be found in every tiny detail of the facility. And that is why, although this

particular article is about our visit to the A. Smith Bowman distillery, the

true subject here is Jay Adams, who is the REAL Virginia Gentleman… The story of Bowman’s dairy

farm and distillery starts in Fairfax County, sixty miles north of

Fredericksburg, where the town of Reston now lies.

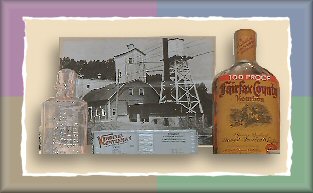

Abram Smith Bowman himself had come to Virginia in

1927 from Kentucky. Purchasing some 4,000 acres of what was supposed to have

become the town of Wiehle, he renamed it Sunset Hills Farm and established a

dairy. Subsequent land purchases brought the farm to over 7,000 acres.

Whether he augmented his dairy business with the byproducts of corn-based

cattle feed is not recorded, but immediately upon repeal of prohibition in

1934 he built a distillery just north of the railroad, which he ran with his

sons, Smith and Delong. Smith Bowman began bottling Virginia Gentleman

Bourbon in 1937. They later added another brand, Fairfax County Bourbon.

Although they were a small outfit, even local sales so outstripped the dairy

that they felt comfortable selling, in 1960, all but 60 acres to Simon and

the town of Reston, continuing to operate the distillery on the

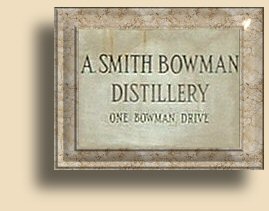

remaining property. In 1988 the distillery moved from Reston to

Fredericksburg. The reasons for the move are not completely clear, but there

appear to be elements of altruism toward the growing community of Reston, a

need to expand the facilities to accommodate the distillery's own growth,

perhaps environmental concerns, and also perhaps the opportunity to apply

some of Reston's utopian community ideas to another venue. There were about

45 employees working for A. Smith Bowman at the time and all were encouraged

to make the sixty-mile move with the company. The new site in Fredericksburg was that of the FMC Cellophane manufacturing plant, which had been vacant and decaying for nearly a decade. The company needed a site that would accommodate both current and future expansion requirements, be strategically located to major highways, and have rail access. It would also be a huge challenge to adapt such a facility to the needs of a modern beverage alcohol distillery while accommodating Adams' vision for the site as a whole. The following owes heavily to an article by Christopher T. Limbrick in the August 1999 issue of the RESTORATION JOURNAL. Christopher is a general contractor and also the managing director of Bowman Real Estate Commercial. The FMC location is very large, far larger than the distillery's immediate needs, and the project's scope extended over the entire site, with the idea of developing and leasing out unneeded facilities to other businesses. The same attitudes and beliefs that had inspired Weihle and Simon found new expression at No. 1 Bowman Drive as the plans began to be drawn up. First and foremost, of course, Adams wanted a vibrant, modern, and efficient beverage alcohol distillery. But the scope of his ideas went well beyond that. His vision was of a complete business and industrial campus, integrated around the distillery's buildings, with a single, coherent theme and design. It would also need to be attractive to other businesses. Additionally, it was important that the

new facility look “old”. The original buildings were constructed by American

Viscose in 1920, at a time when art-deco was a very popular and modern look

in furniture, sculpture, paintings, and architecture. Even industrial

architecture. That fact, in addition to the social importance of the site,

struck a chord in Jay Adams' soul. Adams values highly the patina of age and

experience and he felt it important to express that.

Limbrick describes Adams as having “the heart of a preservationist and the vision of a pioneer”, and together they set out to rebuild the industrial park. As with any restoration project, there was a tremendous amount of planning, research and plain, old, hard work. But converting the old, long-abandoned cellophane factory to use as a distillery, while maintaining that feeling of oldness and art-deco-era roots, was truly a challenge of monumental proportions. Adams was also quoted as saying, "We really ought to try to preserve as many of the different structures as we can. I think it's best to try to leave the buildings as much as they are." And that’s exactly what they did. Characterized by Limbrick as one of the most ambitious economic development projects in the state, what would become The Bowman Center would require the combined efforts of county officials, economic development offices, the Bowman Companies, and countless architects, engineers, consultants and contractors. Many of the buildings featured textured

glass blocks, a popular architectural feature of the art deco period.

Workers preserved these blocks in many areas and replaced them in damaged

areas. New, painstakingly-selected bricks match those weathered and

time-worn from many years of industrial use.

Interior spaces were preserved as well.

Jay Adams' own office, for example, looks quite similar to the way it must

have when the general manager of the

Sylvania Plant occupied it in the '20s. The original wood panels, trim,

lighting fixtures and windows are intact.

The paintings on the walls, too, have

been selected individually to suit his varied and eclectic taste. Taste - an

hour with Jay Adams and one wonders why anyone would ever use that word in

reference to anyone else. Taste, and understatement.

We visit for awhile with Jay in his

office. We hadn't expected to be as awestruck as we are. And then Jay takes

us out to see the distillery itself.

As we enter the production facilities,

he points out the ceilings, which were too low for the equipment that need

to be set up. These were, of course, not really "ceilings" but rather the

two-foot thick We turn a corner... and there it is. Whiskey that has been run

only once through a still often tastes very harsh. Most bourbon is distilled

twice, the process called "doubling". It doesn't really double

the alcohol, but it does raise it a little, and smoothes the liquor a

lot, by removing more of the undesirable flavor elements. Although the original distillation

of bourbon is

nearly always performed using a continuous-style still (sometimes called a

beer still or column still), the doubler itself is often really a small pot still.

The condensed, low-proof liquid distillate is put into the doubler and

heated. The vapors are drawn off and condensed again. Just like any other pot

still. In most distilleries, the condensed distillate comes directly from

their column still and is simply piped over to the doubler. In Ireland it's traditional to distill the whiskey yet a third time, but that's not common practice elsewhere. Virginia Gentleman is distilled a third time. The fermentation of the grain mash and the first two distillations take place at the Buffalo Trace Distillery, in Kentucky, which has supplied their base distillate for over fourteen years. The twice-distilled wash is then sent from the doubler to a third pot still, this one located at A. Smith Bowman.

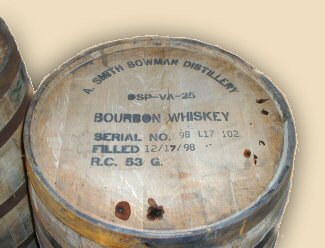

And that's why it's not bourbon yet, nor even whiskey. So, although the A. Smith Bowman

Distillery doesn't

process grain, and doesn't cook and ferment sour mash, and doesn't even run

the mash through the preliminary distillation step, the product that

undergoes the final distillation in Virginia and which is then put into

those new,

charred oak barrels and stored for four or more years in a Virginia

warehouse is the exact same liquid.

Barrel storage at Bowman is also different from the way most other distilleries do it. The barrels are not stored on their sides in ricks. They're stored upright on palettes stacked atop one another. Jim Beam also uses this method of palletized barreling, which makes handling of the barrels much easier, in their cavernous warehouses. Whether it's the way the barrels are stacked, or the temperature of the sealing wax, or the airflow around the holding tanks, Jay makes you feel as though he built the whole distillery with his own hands. And, while it's possible that there might be some part of the operation Jay is not capable of doing himself, you'd have a hard time trying to convince any of us of that after this morning. Before we say goodbye Jay takes us

out to another section of the facility to show us one more of his artistic

creations. He had mentioned this work earlier, but only showed it to us

because of our repeated insistence.

Of course, a four-story tall copper gateway made from two bourbon stills is something only a born artist would have ever imagined. And constructing such a thing is something only a born engineer would even consider actually doing. And the restraint and poise to casually mention to some guests, almost as an aside, a sculpture which, if commissioned by an art museum or a technical university would rate inclusion in tourist guidebooks is something only a true born gentleman might possess. And, considering that those towers were

constructed at a time when all eyes (especially those of investors) must

have been pointed into the future --

But there, sixteen years ago, was Jay

Adams, executive, engineer, tinkerer, designer, and artist, standing between

his column stills and the wrecker's ball, saying (probably softly and

politely), "Listen up now, You can have the buildings, and the fermenting

tanks, and the yeast tubs.

It's been a memorable morning, and a fascinating look at a very different sort of bourbon whiskey distillery. But the image that will linger on is of that gateway, and Jay Adams, the real Virginia Gentleman.

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2004 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

is

a copper pot still. A little later on in this story, We'll see how

Joe makes true, authentic (and legal) bourbon whiskey without ever touching

a single kernel of corn, using just this copper pot still.

is

a copper pot still. A little later on in this story, We'll see how

Joe makes true, authentic (and legal) bourbon whiskey without ever touching

a single kernel of corn, using just this copper pot still.

The area had been the

site of a planned utopian community both before and after the Bowman family

lived there. In the 1890’s Dr. Carl Adolph Max Wiehle laid out a idealized

planned community that never came to pass, and in the 1960’s architect

Robert E. Simon, of Carnegie Hall fame, began laying out the city of Reston

(using his own initials as the name, R.E.S.ton),

which may be one of the most successful planned communities of all time, on

land purchased from the farm.

The area had been the

site of a planned utopian community both before and after the Bowman family

lived there. In the 1890’s Dr. Carl Adolph Max Wiehle laid out a idealized

planned community that never came to pass, and in the 1960’s architect

Robert E. Simon, of Carnegie Hall fame, began laying out the city of Reston

(using his own initials as the name, R.E.S.ton),

which may be one of the most successful planned communities of all time, on

land purchased from the farm.

The

complex wasn't just another factory in an industrial town; it was, and is,

a central part of Fredericksburg's landscape and history. Known as "The

Plant" when FMC closed it in 1978, it employed over 1,100 people,

manufacturing cellophane and rayon 24 hours a day. For over forty-eight

years it had been the only major employer in Fredericksburg other than the

federal government.

The

complex wasn't just another factory in an industrial town; it was, and is,

a central part of Fredericksburg's landscape and history. Known as "The

Plant" when FMC closed it in 1978, it employed over 1,100 people,

manufacturing cellophane and rayon 24 hours a day. For over forty-eight

years it had been the only major employer in Fredericksburg other than the

federal government. To further preserve the era and

capture some of that old spirit, such names as the Sylvania Building and the

Stores Building identify newly renovated structures and reflect the

activities of the day. Of course, other signs, such as Bourbon Street, tie

those old ideas in with the current usage.

To further preserve the era and

capture some of that old spirit, such names as the Sylvania Building and the

Stores Building identify newly renovated structures and reflect the

activities of the day. Of course, other signs, such as Bourbon Street, tie

those old ideas in with the current usage. And in every detail there is something

from the soul of Jay Adams. Each building in the complex, for example, is

marked with an icon made of tiles. It’s not obvious; in fact, one would

hardly even notice. Except that the exact pattern of colors in the tile

marker is reproduced on the road signs and on Jay Adams’ business card.

And in every detail there is something

from the soul of Jay Adams. Each building in the complex, for example, is

marked with an icon made of tiles. It’s not obvious; in fact, one would

hardly even notice. Except that the exact pattern of colors in the tile

marker is reproduced on the road signs and on Jay Adams’ business card.  Wall and floor coverings fit the

patterns and designs of the established art deco compositions. But there are

differences that are very unique to Jay Adams. Among the most striking of

these differences are the paintings and furnishings he's chosen, not just in

his own office but throughout the administration building. All are

exquisite. And each has its own story, which Jay will happily relate. Some

of the furniture in his office was found at auctions and flea markets. You

say that beautiful side table in his office looks perfect? Well, it isn't.

Jay will quickly point out that the whole side is busted and the piece is

set so you won't see it.

Wall and floor coverings fit the

patterns and designs of the established art deco compositions. But there are

differences that are very unique to Jay Adams. Among the most striking of

these differences are the paintings and furnishings he's chosen, not just in

his own office but throughout the administration building. All are

exquisite. And each has its own story, which Jay will happily relate. Some

of the furniture in his office was found at auctions and flea markets. You

say that beautiful side table in his office looks perfect? Well, it isn't.

Jay will quickly point out that the whole side is busted and the piece is

set so you won't see it.

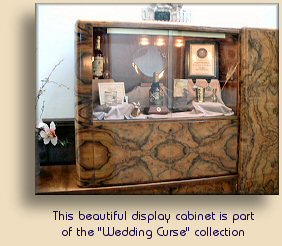

He's

not ashamed of that. He's going to finish restoring it someday when he has a

chance. Like he already has done for most of the other pieces. He didn't buy

them from a designer. Nor did a designer supply the drop-dead breathtaking

pieces of tiger-maple art-deco furniture, pieces of which are scattered

throughout the offices as they fit. This is an extensive set, with several

items, and he didn't buy them all at the same time. As with so many of the

treasures Adams has contributed, there is a fascinating (and very funny)

story about this furniture and the people who have owned it. John calls it

the "Wedding Curse" suite, and you'll just have to ask Jay to tell you about

it when you visit him.

He's

not ashamed of that. He's going to finish restoring it someday when he has a

chance. Like he already has done for most of the other pieces. He didn't buy

them from a designer. Nor did a designer supply the drop-dead breathtaking

pieces of tiger-maple art-deco furniture, pieces of which are scattered

throughout the offices as they fit. This is an extensive set, with several

items, and he didn't buy them all at the same time. As with so many of the

treasures Adams has contributed, there is a fascinating (and very funny)

story about this furniture and the people who have owned it. John calls it

the "Wedding Curse" suite, and you'll just have to ask Jay to tell you about

it when you visit him. John

says that a jazz musician once told him the trick to playing "cool" jazz

correctly is work yourself up to a fever pitch, to where you just want to

scream... and then whisper instead. Similarly, Jay Adams’ personality seems

to “leak out through the cracks” despite his ability to be polite, and

dignified, and low-key, and, well, cool. He loves the look of

the '20s, and is quick to point that out. He won't mention the paintings

directly, but you quickly notice that each seems to be a unique example of a

particular style. Hanging next to an art-nouveau treatment might be an

impressionist landscape, or a cubist work, or maybe even something

Florentine. Each artwork selected on its own merits, and each a sort of

postcard or snapshot of the important thing, which is the story behind why

it's there. We have acquired a fairly comprehensive collection of

now-only-partially-full American whiskey bottles, and that's exactly the

philosophy behind the items we have on display.

John

says that a jazz musician once told him the trick to playing "cool" jazz

correctly is work yourself up to a fever pitch, to where you just want to

scream... and then whisper instead. Similarly, Jay Adams’ personality seems

to “leak out through the cracks” despite his ability to be polite, and

dignified, and low-key, and, well, cool. He loves the look of

the '20s, and is quick to point that out. He won't mention the paintings

directly, but you quickly notice that each seems to be a unique example of a

particular style. Hanging next to an art-nouveau treatment might be an

impressionist landscape, or a cubist work, or maybe even something

Florentine. Each artwork selected on its own merits, and each a sort of

postcard or snapshot of the important thing, which is the story behind why

it's there. We have acquired a fairly comprehensive collection of

now-only-partially-full American whiskey bottles, and that's exactly the

philosophy behind the items we have on display. Of course, we're pretty familiar

with distillery tours. So are our friends. We've all been on tours of other

distilleries. Some of those tours have been given by tour guides employed for

that purpose; others have been given by master distillers, or corporate officers,

or plant managers. In another page we describe our visit with

Of course, we're pretty familiar

with distillery tours. So are our friends. We've all been on tours of other

distilleries. Some of those tours have been given by tour guides employed for

that purpose; others have been given by master distillers, or corporate officers,

or plant managers. In another page we describe our visit with

reinforced concrete floors of the second story, and they needed to be

removed very carefully in order to preserve the structural integrity.

reinforced concrete floors of the second story, and they needed to be

removed very carefully in order to preserve the structural integrity.

But it would take over 500 miles of pipe to get

it to Fredericksburg from Frankfort. So they ship it in

tanks instead. The important thing is what they don't do. They

don't put it into new, charred oak

barrels.

But it would take over 500 miles of pipe to get

it to Fredericksburg from Frankfort. So they ship it in

tanks instead. The important thing is what they don't do. They

don't put it into new, charred oak

barrels.  It's the barreling and storage that makes Virginia Gentleman a true bourbon

whiskey. And it's that final distillation, here in Fredericksburg, that

makes it Virginia Bourbon Whiskey.

It's the barreling and storage that makes Virginia Gentleman a true bourbon

whiskey. And it's that final distillation, here in Fredericksburg, that

makes it Virginia Bourbon Whiskey. It's

a sort of "junk-art" gateway, made from the old two column stills from the

Sunset Hills site. They have been erected on either side of a driveway, and

then connected to one another with copper pipe to form a gateway. A

four-story tall gateway, which allowed us to see, for the first time, what a

bourbon column still really looks like. You see, there are usually floors

built around the column for access, so you never see the whole thing at

once. It is certainly an awesome sight.

It's

a sort of "junk-art" gateway, made from the old two column stills from the

Sunset Hills site. They have been erected on either side of a driveway, and

then connected to one another with copper pipe to form a gateway. A

four-story tall gateway, which allowed us to see, for the first time, what a

bourbon column still really looks like. You see, there are usually floors

built around the column for access, so you never see the whole thing at

once. It is certainly an awesome sight. and

into the cost estimates of that future, and that the scrap value of those

all-copper columns and piping was not a trivial matter, only a born leader

and corporate fighter would have the courage to tear those two useless pieces

of old machinery from the grasp of the salvager and the accountant.

and

into the cost estimates of that future, and that the scrap value of those

all-copper columns and piping was not a trivial matter, only a born leader

and corporate fighter would have the courage to tear those two useless pieces

of old machinery from the grasp of the salvager and the accountant. You can haul away the plumbing and the wiring and the lumber and the

bricks. But these here are the stills my whiskey poured from every day, and

you'll not be taking these columns for your precious scrap pile".

You can haul away the plumbing and the wiring and the lumber and the

bricks. But these here are the stills my whiskey poured from every day, and

you'll not be taking these columns for your precious scrap pile".