Woodstone Creek Distilling Company

Cincinnati,

Ohio

|

American

Spirits:

March 13, 2011 -- Ohio's Bourbon |

|

|

|

|

Cincinnati, the one-time Queen of American Whiskey

When most of us buy a carton of milk, we don't expect -- or even want -- it to

come to us just as it left the cow.

Yes, there are those who do prefer it that

way, and they should certainly be able to enjoy their preference unhindered.

They can enjoy long discussions among themselves on dairy-aficionado-oriented

websites, debating the quality and flavor nuances of Tom Taylor's raw milk

(which is only available at four locations in his county) versus that of

Billy-Bob McGuinn's (obtained directly from his farm).

One thing they'll

probably all agree on, though, is that both are vastly superior to the

homogenized, pasteurized, adulterated stuff that common folk like us buy in our

supermarkets. And maybe they're right; who knows?

One thing they'll

probably all agree on, though, is that both are vastly superior to the

homogenized, pasteurized, adulterated stuff that common folk like us buy in our

supermarkets. And maybe they're right; who knows?

The same can be said about whiskey, too, of course – and it often is.

Much of modern American whiskey's image, its sense of

"class" and "quality", like that of the single-malt scotch its marketers have so

tried to emulate, is based upon a word highly treasured, if not always among the

marketers themselves, then at least among those they fancy as their customer

base. That word is "heritage". Its use summons images of "Grandpa’s fine

old hand-craftsmanship", "classic standards", "the old homestead", and even "The

Founding Fathers". The truth, however, is that, despite the indisputable

integrity of our beloved grandfather (and yours, of course), not everyone involved in the

intoxicating beverage industry has always been of what we might call the highest

moral character.

In the history of commercial distilling, it seems that for

every whiskey-maker who put his heart and his honor into his product there was

at least one other who'd gladly sell you anything that would fool you into

parting with your money. Probably more than one. Shamefully, they were often

quite successful.

In the history of commercial distilling, it seems that for

every whiskey-maker who put his heart and his honor into his product there was

at least one other who'd gladly sell you anything that would fool you into

parting with your money. Probably more than one. Shamefully, they were often

quite successful.

And perhaps nowhere was that more evident than in the lovely riverfront city of Cincinnati, Ohio.

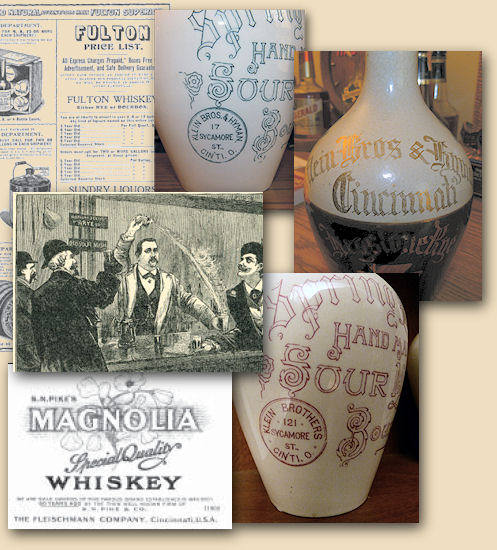

It’s hard to believe, considering the near-total absence of remaining examples, but before Prohibition -- well really over a decade earlier, before the Federal Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 -- the city of Cincinnati was the unquestioned capital of the whiskey industry in all of North America.

But that was exactly what it was. According to the 1894 edition of “The History of Cincinnati and Hamilton County” there were, at the time, no less than nine full distilleries and some 58 rectifying plants, representing well over $28 million (1890s) annual dollars worth of commerce, in Cincinnati and its Ohio suburbs (Northern Kentucky suburbs just across the river, which were just as prolific, were not included in the study.

The history described the whiskey trade in Cincinnati as “…immense; in fact she is the only great market for standard brands on the continent.”

Among those brands, of course, were included virtually all of the straight bourbons originating in Kentucky and a large number of Pennsylvania and Maryland rye whiskies. But a significant part (about a third) were what might graciously be called “mercantile whiskey”. And with the Pure Food & Drug Act’s requirement for truth in labeling, many of those merchants simply vanished or moved on to less regulated businesses. By the time the 18th Amendment shut down both the distillers and the blenders, most of the existing Cincinnati brands had been sold by their original owners to brokers and trusts. After Repeal, Cincinnati never regained its position (or really even tried to), and Illinois became the center of the blended whiskey trade.

The somewhat derogatory term, “Cincinnati whiskey” still remained, however.

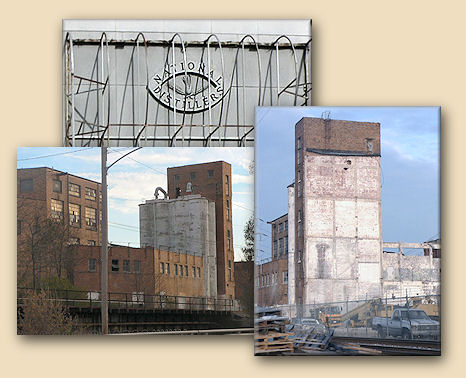

Also remaining is a single major distillery, albeit no

longer a whiskey distillery.

Among the many properties acquired by National

Distillers Products Corporation during the 1930s was the Carthage Distillery in

Elmwood, a Cincinnati suburb. They rebuilt part of it as an industrial (neutral

spirits) alcohol distillery in the ‘40s, providing material for the war effort,

and continued afterward to use it to make DeKuyper cordials. They also kept the

bottling and shipping facilities. For some time Old Overholt rye whiskey, which

they also owned, was bottled there, although we haven’t found any evidence that

it was ever actually made there. Both products were still being produced or

bottled at Elmwood when National Distillers was itself purchased by Jim Beam’s

company in 1987. Beam Global still operates the DeKuyper plant, but (we believe)

Old Overholt has moved to their Frankfort, KY plant. Thus there is no whiskey

coming from the Elmwood distillery anymore, even whiskey only bottled there.

Among the many properties acquired by National

Distillers Products Corporation during the 1930s was the Carthage Distillery in

Elmwood, a Cincinnati suburb. They rebuilt part of it as an industrial (neutral

spirits) alcohol distillery in the ‘40s, providing material for the war effort,

and continued afterward to use it to make DeKuyper cordials. They also kept the

bottling and shipping facilities. For some time Old Overholt rye whiskey, which

they also owned, was bottled there, although we haven’t found any evidence that

it was ever actually made there. Both products were still being produced or

bottled at Elmwood when National Distillers was itself purchased by Jim Beam’s

company in 1987. Beam Global still operates the DeKuyper plant, but (we believe)

Old Overholt has moved to their Frankfort, KY plant. Thus there is no whiskey

coming from the Elmwood distillery anymore, even whiskey only bottled there.

So, how does any of this relate to Cincinnati today?

Simple: just two words...

Woodstone Creek

For as long as they've been distilling spirits in

Cincinnati, and it’s been a lot longer than you might think, Don and Linda

Outterson have been trying to produce exactly the opposite of what "Cincinnati

Whiskey" was once so well-known for. That is, they are producing innovative,

non-standard, unexpected, unique, and highly artisan distilled spirit products,

at an extremely small scale, intended for those few people who really care about

such craftsmanship and are not afraid to pay for the opportunity to possess and

enjoy some. It has to be just a few people, because they only produce a handful

of barrels a year.

Just what kind of operation is Woodstone Creek? And how did it happen to get a name like that, considering that it's located in a 1500 square foot partition of a small brick and concrete block former stamping factory building in an “urban redevelopment” area, practically across the street from Cincinnati’s Xavier University?

Well, it actually started a bit more rurally about fifty miles north (where there actually were some stones, and woods, and even a creek). Even then it was hardly a gran cru class estate winery -- the kind you see in pictures, with a huge white plantation home surrounded by rolling first-growth vineyards. Just a small family winery that was successful enough to have outgrown its space after just two years. The winery, that is; the vineyards and hives there are still the source for much of their grapes and honey.

The idea to move to the city came from a visit to several

California wineries that were set in gentrified urban locations. Fascinated by

the possibilities, they decided to make such a move themselves. The area has yet

to become “urban chic”, but they’re hoping it will – and doing their part to

provide an interesting destination. The Woodstone Creek tasting room was once

the factory president's wood-paneled office. The tasting itself is done on a

beautiful hand-crafted 1930’s curved bar, built of mahogany and maple and

polished to a gleam. It is a lovely place to enjoy samples of their wines

(they’re not allowed to offer tastings of their distilled products there --

yet).

Typical of the Outtersons, though, the expressions they’re most proud of

are ones you’ve probably rarely (or never) encountered, including a wide

selection of mead (ten varieties), pyment, aged metheglin, and proprietary

styles.

Typical of the Outtersons, though, the expressions they’re most proud of

are ones you’ve probably rarely (or never) encountered, including a wide

selection of mead (ten varieties), pyment, aged metheglin, and proprietary

styles.

Also typical is their philosophy of multiuse of space; the

room is also their bottling area, product case storage, and general office.

When

you are bottling less than 200 cases a year -- total -- you don’t need a full

bottling and labeling department – Linda Outterson does it all by hand.

When

you are bottling less than 200 cases a year -- total -- you don’t need a full

bottling and labeling department – Linda Outterson does it all by hand.

And those lovely paintings on the wall are also Linda’s work.

While their wine-making skills are top-notch, Don Outterson himself may be more familiar to those who remember the birth of home brewing in the mid 1970s, when the prohibition against it was finally lifted. Don’s books about making beer, along with those of Charlie Papazian and Bill Owens, made up much of the knowledge upon which those who would become the movers and shakers of today’s microbreweries based their education.

There does happen to be a home-brewing store in the same building, adjacent to Woodstone Creek’s portion, but the Outtersons aren't related to it in any way except as friendly neighbors.

And the Woodstone Creek still itself? Well as you approach

the building, you won’t see the four-story section you might normally expect to house

the column still; because there is no column still. And if you were to be

invited into the actual distillery part of the Outtersons’ domain (there are no

public tours offered at this time – heck,

Don and Linda just managed to get the

state of Ohio’s permission to even sell their product onsite, much less take

folks around -- give ‘em time, though), you won’t find the sort of jewel-like

European polished copper, steel, and brass objet d'art you might expect

(especially considering what Don manages to get out it). No, Woodstone Creek

spirit is produced from a 238-gallon, unpolished stainless steel direct-fired

pot still which Don engineered himself. Great care has gone into its design and

construction, along with everything Don Outterson knows, taking into account

just how distilled spirit actually vaporizes, condenses, and should be

contained, and he credits his attention to those details as a major difference

between his spirit and that of other distillers. He pays every bit as much

attention to such factors as the grain recipe (for bourbon, that's five grains: white and yellow

corn, rye, and two varieties of barley) and yeast (don’t bother to ask; he won’t

tell you).

Don and Linda just managed to get the

state of Ohio’s permission to even sell their product onsite, much less take

folks around -- give ‘em time, though), you won’t find the sort of jewel-like

European polished copper, steel, and brass objet d'art you might expect

(especially considering what Don manages to get out it). No, Woodstone Creek

spirit is produced from a 238-gallon, unpolished stainless steel direct-fired

pot still which Don engineered himself. Great care has gone into its design and

construction, along with everything Don Outterson knows, taking into account

just how distilled spirit actually vaporizes, condenses, and should be

contained, and he credits his attention to those details as a major difference

between his spirit and that of other distillers. He pays every bit as much

attention to such factors as the grain recipe (for bourbon, that's five grains: white and yellow

corn, rye, and two varieties of barley) and yeast (don’t bother to ask; he won’t

tell you).

Click here for more and larger photos of the distillery

We are accustomed to visiting distilleries whose capacities

are in the 400 barrel-a-day range (for Buffalo Trace) down to a minuscule 15

barrels/day for Woodford Reserve. The Jack Daniel’s distillery puts out 2,200

barrels daily, and they’re not working at their full capacity. Don is not a

full-time distiller; he has a day job (he’s a CPA and customer service

representative for – can you believe it? – the Treasury Department). He distills

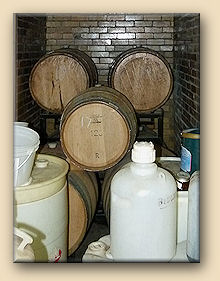

as time permits, about ten to fifteen gallons... a WEEK!

It takes him nearly a

month to fill just one barrel, and even that’s deceptive, because he’s usually

working on more than one spirit product at any given time. No fancy,

climate-controlled warehouses here, either; barrels are stuffed into every nook and

cranny in the place. The temperature of which is kept relatively even, except

that it raises when the still is in use, or when mash is being cooked – since

all that happens in the same part of the building, too.

It takes him nearly a

month to fill just one barrel, and even that’s deceptive, because he’s usually

working on more than one spirit product at any given time. No fancy,

climate-controlled warehouses here, either; barrels are stuffed into every nook and

cranny in the place. The temperature of which is kept relatively even, except

that it raises when the still is in use, or when mash is being cooked – since

all that happens in the same part of the building, too.

Click here for even more photos

It’s a lot like watching someone build a world-class race

car in their basement.

Except that it’s several race cars. And they all win lots of races.

Are the results really as exclusive as all that? They certainly are!

In fact, many of the spirits Don distills and ages can’t even be sold

at this time.

There simply aren’t any government-approved categories for

labeling it.

Yet.

Even spirits one wouldn’t ordinarily think of as “flavorful”

benefit from Woodstone Creek’s touch.

While they patiently waited for their

whiskey to mature (no wood chips or itty-bitty barrels here; full-size charred

53-gallon oak, only, and brand new barrels for the bourbons, of course) they sent some of their

higher-proof spirit out into the world as Woodstone Creek Vodka.

What do you think happened?

It came back with awards and medals.

But it’s really only “vodka” because the government insists on it being labeled that way. Nearly all vodka is 100% neutral spirits distilled at 190 proof or better and diluted to a reasonable strength for bottling. Distilled from corn at only 160 proof, Don’s vodka can’t even be called “neutral spirits”, although it’s still okay to call it vodka, which they do. But it carries flavors that would ordinarily never be found in vodka. More like unaged whiskey -- but with finesse. If there is such a thing as “sipping vodka”, this would be it.

Could Don and Linda’s five-grain bourbon be the best

American whiskey (or distilled spirit) you've ever tasted?

Probably not, if what you're looking for is another example of what you already

know.

Is it the best American whiskey (or distilled spirit) ever

made?

It

just might be. We can't see any reason to doubt that, other than conformity to

current standards. We do know that it's won awards in every competition it’s

entered, and we do know that Jim Murray, in his book “The Whisky Bible” (2009)

called Woodstone Creek's single malt barley whiskey “brilliant” and rated it as 92 on a scale where 12- and 18-year-old Macallan scotches are in the high 80s.

It

just might be. We can't see any reason to doubt that, other than conformity to

current standards. We do know that it's won awards in every competition it’s

entered, and we do know that Jim Murray, in his book “The Whisky Bible” (2009)

called Woodstone Creek's single malt barley whiskey “brilliant” and rated it as 92 on a scale where 12- and 18-year-old Macallan scotches are in the high 80s.

But that isn’t what makes it so special to us (well, okay,

we suppose we can’t deny that, since it’s being produced in our home town, that has

to have at least

some influence for us).

But it’s something very different from that. And something very unexpected…

Recently we had an opportunity to open and taste from a bottle of Old Burnett Straight Whiskey which was made (or at least bottled) by the Sherbrook Distillery Co. in Cincinnati well before Prohibition – in fact, probably before 1910. As is often the case with these old, never-opened bottles, the whiskey inside was brilliantly clear and tasted perfect – just the way it must have back then. But one sip and everyone present was shocked… it tasted nearly identical to the bourbon made today (well, a few years ago anyway; after all this is aged bourbon) by Woodstone Creek. A few minutes later and we were tasting samples side-by-side.

Okay, so they weren't identical; but it was eerie just how similar these two whiskies are to one another – and how completely different they both are from other whiskies available today.

Without any prior direct knowledge of what early Cincinnati whiskey might have tasted like, it seems as though Cincinnatian Outterson has created a straight bourbon whiskey that truly appears to be of the same (somewhat eclectic) style as the Old Burnett from over a hundred years ago. Knowing Outterson’s dedication to his craft, even if he did know the taste of Cincinnati whiskey historically, he probably wouldn’t have tried to emulate it. But the fact is that he very likely makes his whiskey (and all his spirits – just wait until Linda Outterson comes up with a way to label and market some of the others) the same way as whoever made the whiskey in that old bottle.

Should you do whatever is necessary to get hold of some and

try it?

Well, you’re reading this page, aren’t you?

|

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright ©2011 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |