|

|

|

| American

Spirits:

May 2011 -- Kentucky's Whiskey History all in one place! |

|

|

|

|

The "1792" is a celebration of the fact that Kentucky, until then a large county in the Commonwealth of Virginia, separated and became the 15th United State (actually also a commonwealth) in that year. The rest of the bourbon's name, Ridgemont Reserve, also has a story, but we won't go into it here. It is a funny story to some, although perhaps not so funny to others.

Regardless of its name though, many who enjoy this bourbon believe it to be a specialty item, the sole product of a distillery dedicated to that particular brand, as is true of Woodford Reserve or Maker's Mark. Others think of it as a fine example of bourbon whiskey produced by a bottler who does not directly distill, but carefully selects the finest examples for his brand from existing distillers. Examples might be brands such as Jefferson Reserve, Noah's Mill, Corner Creek, and, at one time, Wild Turkey and the Van Winkle bourbons.

Both are wrong.

1792 Ridgemont Reserve bourbon is mashed, distilled,

aged, and bottled entirely at this distillery. It is NOT, however, the

only whiskey made here. Far from it. Like many distilleries built in the

years immediately following the repeal of National Prohibition, the Barton

distillery produced and aged whiskey as a commodity for use by other companies, in

addition to whiskey made for their own regionally distributed brand. But

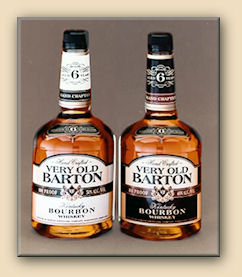

Barton's own regionally distributed brand was -- and remains -- Very Old

Barton. Most often called just “VOB”, it has been one of the most popular

brands of bourbon in Kentucky since the early 1940s. By the way, the “very old” part of VOB means six years – not so

very old by today's standards, but remarkable at a time when nearly all

bourbons were aged no more than four years. The Schenley company at that

time marketed a 6-year-old version of their own bourbon as "Ancient Age",

and they called their 10-year-old "Ancient Ancient Age".

Like many distilleries built in the

years immediately following the repeal of National Prohibition, the Barton

distillery produced and aged whiskey as a commodity for use by other companies, in

addition to whiskey made for their own regionally distributed brand. But

Barton's own regionally distributed brand was -- and remains -- Very Old

Barton. Most often called just “VOB”, it has been one of the most popular

brands of bourbon in Kentucky since the early 1940s. By the way, the “very old” part of VOB means six years – not so

very old by today's standards, but remarkable at a time when nearly all

bourbons were aged no more than four years. The Schenley company at that

time marketed a 6-year-old version of their own bourbon as "Ancient Age",

and they called their 10-year-old "Ancient Ancient Age".

One thing that makes Barton so interesting to folks who want to know more about the way the whiskey industry in America developed and grew, is that you can get a good picture, with Barton, of how the classic bourbon distilleries of Kentucky really operated, before (most of them) became little more than the “bourbon division” of much larger spirits corporations. And in fact, that process itself is a big part of this company’s own history – both from the very beginning, and with its most recent history as well.

Y'see, it all started a long time ago, with John Graves Mattingly,

of Marion county.

In the mid 1800s, he was involved with several very early

distilleries, including J. G. Mattingly & Sons in Louisville in 1845 and the

Marion County Distillery (also in Louisville, by the way, not in Marion County) in 1866.

The "sons" were John G. and Benjamin S. Mattingly. Ben Mattingly’s own son was

Benjamin F. Mattingly, and he had the good sense to marry Catherine Willett. That's important,

because the Willetts are another

fine old Kentucky family, very prominent in the world of bourbon-distilling.

They still are. And

one of the companies they owned was Willett & Frenke, also in Louisville,

of course, which

operated a distillery at Morton’s Spring in Nelson County, just south of

Bardstown. Then Thomas S. Moore, another distiller,

also married into the Willett family, and he went to

work at that distillery in 1874, joining with his brother-in-law, Ben Mattingly.

Then Thomas S. Moore, another distiller,

also married into the Willett family, and he went to

work at that distillery in 1874, joining with his brother-in-law, Ben Mattingly.

In 1876, their joint father-in-law (John D. Willett) transferred

all his interest in the company to them (well, probably it was to their wives - his daughters

- but legally it was to Tom and Ben), and they began operating the distillery as

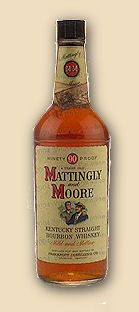

Mattingly & Moore (we're not sure whatever happened to Frenke). They made Mattingly

& Moore bourbon, along with Belle of Nelson (named for John

Willett's winning race horse) and Morton’s Spring

Rye, (named for the spring that provided the water for the distillery).

However, in 1881 – about the time the first barrels of their bourbon

were coming of age – Mattingly sold the company to a group of investors. Tom

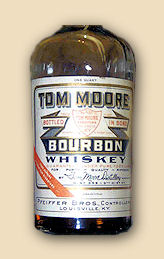

Moore continued to work with the new company until 1899, when he bought 116

acres adjacent to the existing distillery and built his own distillery there, producing

Tom Moore, Dan’l Boone, and Silas Jones whiskey. In 1916 the

company that owned Mattingly & Moore went bankrupt, and the distillery was

acquired by the Louisville company that was their chief distributor. Tom Moore,

himself,

later acquired the property and incorporated it into his own distillery, tearing down the old buildings. The resultant site remains that of

the Tom Moore distillery today.

In 1916 the

company that owned Mattingly & Moore went bankrupt, and the distillery was

acquired by the Louisville company that was their chief distributor. Tom Moore,

himself,

later acquired the property and incorporated it into his own distillery, tearing down the old buildings. The resultant site remains that of

the Tom Moore distillery today.

Except that it is no longer the “Tom Moore Distillery”.

Thomas S. Moore maintained leadership of the company until it was closed by Prohibition, and actually all the way through those years, although they weren’t distilling whiskey anymore. In 1934 his son, Con Moore, re-opened the distillery, but he sold it again, in 1944, to Oscar Getz, a Chicago liquor merchant. Getz changed the name to the Barton Distillery, a name he claimed to have made up and "picked from a hat". They produced two brands of straight Kentucky bourbon, Tom Moore and Kentucky Gentleman. Under Getz's leadership the Barton Distillery company went on to become Barton Brands Limited. When Barton Brands then purchased the Glenmore Distillery in Owensboro, Kentucky (and which was itself made up of several acquired brands from that region), the bottling & shipping facilities were kept, but the distillery itself was shut down. The whiskey for Glenmore's Kentucky Tavern brand is now made here. So is Ten High ,Walker’s Reserve, and Imperial, which were products once made by the Hiram Walker company in Peoria, Illinois. Also, Fleischmann’s Rye as well as several blended whiskies.

And also, if the truth is to be told, the contents of several other brands of fine whiskey have begun life in the fermenting tanks of this distillery.

But nothing really fancy, until they released 1792 Ridgemont Reserve in 2002, which owes much of its current brand image to the aforementioned Hiram Walker company. In the early 1980s Hiram Walker ceased to exist and Barton Brands purchased several of their brands, which they still produce here at their distillery in Bardstown. The concept for the super-premium 1792 brand (and possibly some of the original stock used) came from the Hiram Walker branch of the company. With that brand, and with the success of its marketing campaign, suddenly the rest of the beverage world began to take notice of Barton whiskey.

Not that they were obscure within the spirits industry itself. In 1993, Barton Brands which had been acquiring other brands left and right, was purchased by the Canandaigua wine company, primarily for two reasons. One was their distribution rights for Corona beer; the other was because Canandaigua had recently purchased the Paul Masson and Taylor wine companies -- both of whom were producers of distilled brandy -- and intended for them to be aged and bottled (if not originally distilled) in Bardstown. As we visit today, we can see cases of Paul Masson brandy being bottled and cased. Also Walker's Imperial.

At the end of the decade, Canandaigua developed into Constellation

Brands, and it remains a hugely successful multi-national wine and spirits

corporation marketing every imaginable type of beverage alcohol. Many of their

distilled spirits are produced at this distillery. Until recently, though,

Constellation (and even the branch of it that was Barton Brands) did not

consider American bourbon to be important enough even to include Very Old Barton

in their general listings of products. You could find it in their corporate

catalog, but you had to look hard. There was, apparently, no plan to expand its distribution further than the

Kentucky state line. But then came 1792 Ridgemont Reserve and that changed

everything.

There was, apparently, no plan to expand its distribution further than the

Kentucky state line. But then came 1792 Ridgemont Reserve and that changed

everything.

In 2008, the Barton Brands division of Constellation Brands decided to re-claim their heritage and officially returned the distillery to its former name, the Tom Moore Distillery. There may even have been plans to further exploit the heritage of Tom Moore (the brand is still one that the company produces, but only as a blended whiskey).

We’ll never know, however, because in 2009 the Sazerac Company, of New Orleans, who also own the Buffalo Trace distillery in Frankfort, purchased the entire Barton Brands catalog, including their bottling facility in Owensboro and this distillery in Bardstown. And Sazerac has re-re-named it back to The Barton Distillery. Sazerac has a history of developing a brand's heritage in promoting it and, despite restoring the distillery's name, it would not be surprising to see Tom Moore elevated to a straight bourbon again and promoted as a premium product. They have already indicated that Very Old Barton will continue.

As we said earlier, most people who enjoy Kentucky

whiskey are unaware of this distillery's existence, despite the fact that it’s

actually the only operating distillery in Nelson county. The Jim Beam

company has two

distilleries close-by, but both are in adjacent counties; The Heaven Hill

company maintains a huge

presence here, but their actual distilling

facility has been in Louisville since 1996 when their Bardstown distillery was

destroyed by fire. Kentucky Bourbon Distillers (which is the family

distillery being refurbished by the members of the Willett family) will be the second

Bardstown distillery when they come online, but that hasn’t happened yet as of early

2011.

The Heaven Hill

company maintains a huge

presence here, but their actual distilling

facility has been in Louisville since 1996 when their Bardstown distillery was

destroyed by fire. Kentucky Bourbon Distillers (which is the family

distillery being refurbished by the members of the Willett family) will be the second

Bardstown distillery when they come online, but that hasn’t happened yet as of early

2011.

Another reason that Barton isn’t well-known outside of the immediate area is that people haven't had an opportunity to visit it. Well, that’s not completely true… in fact, the Barton Distillery was not only the first distillery to re-open after the repeal of Prohibition, it was also the first Kentucky distillery to offer public tours, and the only one for a long time. Owner Oscar Getz was a man completely fascinated by the history of distilling in Kentucky, and he was an avid collector of memorabilia. He put all of his treasures into the company museum, which was the centerpiece for the tours. From its beginning in 1957 into the early 1980s, people associated the museum with the distillery tour. The tours began and ended at the museum and no public institution ever captured the feeling of history and importance in this industry as well. His book, "Whiskey: An American pictorial history", published in 1978 became the definitive source for much of what we know as American whiskey for the next two decades. Even today, American whiskey distillery tours often center around a museum (sometimes called a Heritage Center) that tells the story, not only of that distillery, but of whiskey-making in general -- often with displays, artifacts, and framed documents.

When Oscar Getz died in 1983 his wife Emma donated the collection to the city of Bardstown and it was moved to its present location. That would be the Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History, located nearby in Bardstown's historic Spalding Hall, which is a “don’t you dare miss this” place for those interested in knowing more about American whiskey.

In those days, the mystique and fascination of touring a

bourbon distillery was considerably less than it is today. One can find public

tours of many industrial places: dairies, cheese factories, even casket-makers;

and interest in what goes on in a distillery was once just about as keen. It

wasn't until the fascination with single-malt-scotch, and the distilleries that

make them, hit the United States in the early 1980s, along with similar desires,

especially among Asian tourists fascinated with all things American and Western

(with which they associated bourbon), who wished to visit their favorite American bourbons' places

of origin. And by that time, the Barton distillery, now a

not-particularly-significant part of a major wine merchant organization, was no longer interested in

accommodating visitors. It remained so unresponsive to cries for allowing

enthusiasts to see "backstage" that nearly everyone forgot they had ever

offered

touring, let alone that they were pioneers in it.

And by that time, the Barton distillery, now a

not-particularly-significant part of a major wine merchant organization, was no longer interested in

accommodating visitors. It remained so unresponsive to cries for allowing

enthusiasts to see "backstage" that nearly everyone forgot they had ever

offered

touring, let alone that they were pioneers in it.

That is no longer so.

In 2008, along with the decision to reinstate the Tom Moore

name, the distillery became part of the Kentucky Distillers Association's

ambitious public awareness program called the Kentucky Bourbon Trail. The idea

of the Bourbon Trail is to promote Kentucky whiskey brands by attracting

consumers to tour the various distilleries that are associated with the KDA.

Considering the reluctance of some major distilleries (and, quite probably, their

insurance companies) that has not been an easy task. One of the "no-way"

distilleries was Barton/Tom Moore, but they did, indeed, begin to offer tours,

if only on a small, reservation-only basis, and with limited access. Then that

all changed -- big time -- in May of 2011. Under the leadership of Pam Gover,

herself a major influence on Kentucky Bourbon tourism (she was the

executive director of the annual Kentucky Bourbon Festival for many years

running), the tour now begins

and ends in a custom-built visitor center, built on the site of

Getz's original whiskey memorabilia museum, and it includes looks into all phases of producing bourbon

whiskey here.

Then that

all changed -- big time -- in May of 2011. Under the leadership of Pam Gover,

herself a major influence on Kentucky Bourbon tourism (she was the

executive director of the annual Kentucky Bourbon Festival for many years

running), the tour now begins

and ends in a custom-built visitor center, built on the site of

Getz's original whiskey memorabilia museum, and it includes looks into all phases of producing bourbon

whiskey here.

What may be even more interesting, though, is that it turns

out the

touring of the Barton Distillery will not be a part of the Kentucky

Bourbon Trail. Due to disagreements between them, in early 2010 the Sazerac

company dissociated themselves from the KDA, and thus from the Kentucky Bourbon

Trail. Their distilleries, Buffalo Trace and Barton, no longer appear on the

Bourbon Trail's website nor in their literature and maps. In fact the KDA even

filed a lawsuit against Sazerac for using the phrase "Kentucky Bourbon Trail" in announcements and

advertising to explain their absence from the list. We're not sure how the

lawsuit came out, but the fact that there appears to be this much animosity may

make for some interesting distillery-touring. Sazerac offers extensive (and very

well-executed) tours of their Buffalo Trace site, and there is no reason to think

they won't do the same here at Barton. And with Gover in charge, there is every

reason to believe this could turn out to be one of the best tours available --

even if you won't get your Bourbon Trail passport stamped.

In fact the KDA even

filed a lawsuit against Sazerac for using the phrase "Kentucky Bourbon Trail" in announcements and

advertising to explain their absence from the list. We're not sure how the

lawsuit came out, but the fact that there appears to be this much animosity may

make for some interesting distillery-touring. Sazerac offers extensive (and very

well-executed) tours of their Buffalo Trace site, and there is no reason to think

they won't do the same here at Barton. And with Gover in charge, there is every

reason to believe this could turn out to be one of the best tours available --

even if you won't get your Bourbon Trail passport stamped.

Just a month before the tours opened, and again about a week afterward, John and Linda visited the Barton Distillery. In our first tour, conducted privately by Pam Gover, we were not able to see the new visitor center. It was still being constructed at that time. Six weeks later we are here again, this time with other people, among whom are Linda's aunt and uncle, along with her cousin and her husband. The new visitor center opened only a week ago. It is lovely, despite the fact that it is very bare-bones right now. Only time will bring about that comfortable look that comes from historic displays and even more branded merchandise.

|

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright ©2011 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |