May 2, 2003

The farmers who continued distilling ("by the light of the

moon") their own produce for their own use during the late 18th and early

19th centuries were simply dealing with an unworkable situation as best they

could. The authorities, of course, took a dim view of

moonshining. The Frederick County sheriff's department mounted a series of

raids on stills nestled in the mountains between Thurmont and Foxville. One

of those sites, known as Blue Blazes, was set near Harman's Creek, five

miles west of Thurmont. The Frederick Post reported that Blue Blazes Still

was "one of the largest and best equipped in Frederick County" It was a

"steamer"

There is not a trace left of the original moonshine

distillery, of course, but in 1970 the Park Service built a

mountain distillery

exhibit on the site, with a working model of a much smaller still.

That is, it WAS a working model. The Park Service doesn't actually fire it

up anymore, but they used to until around 1989.

The notorious excise tax of 1791 that brought about the

Whiskey Rebellion really only lasted for eleven years.

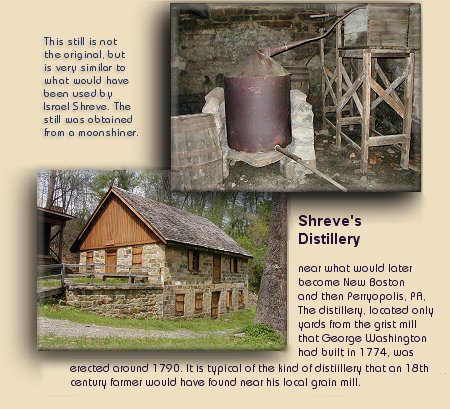

The small distillery operated in Perryopolis by Israel

Shreve was basically the same kind of distillery as this one, only set up

indoors in a stone building. It's likely that the family still that

Abraham Overholt's father operated at their West Overton farm was also

similar in size and style. Shreve's distillery was associated with his

grist mill, and provided distilling services for a fee. Overholt's began

that way, but around 1810 son Abraham transformed the operation into one

that focused on wholesaling the whiskey itself as an end product. The new

trend among commercial distillers was to redefine the grain farmer as a

vendor, rather than as a customer. Instead of paying to have his grain

made into whiskey, the farmer could now take his grain to the distillery

or mill and get cash for it. This was a win-win situation that continued

even after the excise tax no longer existed.

Individual farm distilleries like this one might have

vanished altogether then, except for three factors...

(1) Of course there were always (and still are)

some subsistence farmers whose products serve their immediate family or

can be used for limited trade with bartering partners. However, since

subsistence farmers normally cherish their independence from the general

community, their distilling equipment and methods didn't have a great deal

of effect upon American whiskey distilling as a whole.

(2) Another distilling trend that was gaining favor

involved companies that would purchase farmers' distilled product directly

and then vat them all together, adjusting as needed to compensate for

differences in strength and quality. This is exactly the way such other

agricultural organizations as dairy or fruit cooperatives worked and still

do. In such cases, of course, the individual farmers retained and operated

their small stills, selling only their end product to the distillery.

(3) The tax-free status of whiskeymaking ended with

the onset of the Civil War, and has never returned since then. Once the

excise taxes were returned to the equation, the cost advantages of illicit

production make moonshining profitable. It was really this period between

the Civil War and the beginning of prohibition in the 1920s from which we

get most of our popular images about the hillbilly moonshiners. Once the

production of alcohol was outlawed altogether, the bootleg still of the

'20s and '30s was a much different affair, typically far larger and

operated by far less reputable distillers than had been the case earlier.

Nevertheless, there were stealth advantages in the type of small, easily

set up and taken down operation the old-style farm still provided. Thus,

many of the old pot stills and worms we find in museums, including the

still here at Catoctin and the one displayed at Shreve's, are really old

moonshiners' equipment that might have been still in use in the 1960s.

Click here and

we'll visit the 1790s distillery operated in Pennsylvania by Israel

Shreve...

.

American

Whiskey:

Catoctin

National Park:

Okay, so it's not quite the

Blue Blazes

still...

But it could have been its great-great-grandfather

![]()

FARMERS BEGAN SETTLING the area around

Frederick County, Maryland as early as 1734, and until the

United States Congress passed the 1791 Excise Tax laws, just about every

farm had its own whiskey-distilling apparatus. Even afterwards, it was

perfectly legal to own and operate a still -- provided you registered it

with the Federal government and paid the tax.

It wasn't until passage of the

Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1919 that mere possession of

distilling equipment became a crime. Problem was, in the 18th century, even

if an individual farmer were conscientious about registering his farm's tiny

single still, he had no way to obtain money to pay the tax with. Most of

what a farmer received for selling his surplus crop was in the form of

traded goods and services, and the law required the tax to be paid in United

States currency. The only distillers who could dependably obtain currency

were those producing whiskey on a large enough scale to sell it

commercially.

Of course there were farmers who chose to continue making whiskey

without bothering to register and pay taxes, but over time most found it not

too inconvenient to take their grain to a nearby commercial distillery.

It wasn't until passage of the

Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1919 that mere possession of

distilling equipment became a crime. Problem was, in the 18th century, even

if an individual farmer were conscientious about registering his farm's tiny

single still, he had no way to obtain money to pay the tax with. Most of

what a farmer received for selling his surplus crop was in the form of

traded goods and services, and the law required the tax to be paid in United

States currency. The only distillers who could dependably obtain currency

were those producing whiskey on a large enough scale to sell it

commercially.

Of course there were farmers who chose to continue making whiskey

without bothering to register and pay taxes, but over time most found it not

too inconvenient to take their grain to a nearby commercial distillery. They were also upholding a long colonial tradition of ignoring laws that

didn't suit them. The onset of National Prohibition in 1919, though, brought

an entirely new and different type of distiller into such hard-to-find

places as the Catoctin Mountains around Thurmont, Maryland. These

whiskeymakers were not distilling for subsistence; they were producing

spirits illegally on a large scale, for profit. The going price for "white

lightening" quickly went from around two dollars a gallon to twenty-two.

According to a National Park Service publication, distilling alcohol became

big business in the Catoctin mountains. The mountain provided a secluded

protected area with ready sources of water. Meanwhile, using nearby roads,

moonshiners could ship their product to Baltimore or Washington within a

couple of hours.

They were also upholding a long colonial tradition of ignoring laws that

didn't suit them. The onset of National Prohibition in 1919, though, brought

an entirely new and different type of distiller into such hard-to-find

places as the Catoctin Mountains around Thurmont, Maryland. These

whiskeymakers were not distilling for subsistence; they were producing

spirits illegally on a large scale, for profit. The going price for "white

lightening" quickly went from around two dollars a gallon to twenty-two.

According to a National Park Service publication, distilling alcohol became

big business in the Catoctin mountains. The mountain provided a secluded

protected area with ready sources of water. Meanwhile, using nearby roads,

moonshiners could ship their product to Baltimore or Washington within a

couple of hours.

Very

quickly, local moonshine gained a national reputation, and one might by

surprised at how well-known was the high quality of Catoctin moonshine, even

as far away as New York City.

Very

quickly, local moonshine gained a national reputation, and one might by

surprised at how well-known was the high quality of Catoctin moonshine, even

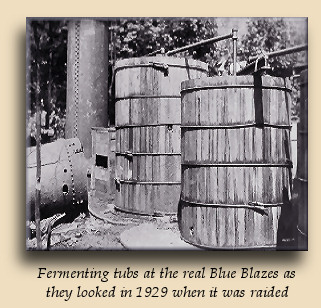

as far away as New York City. type

of still, with a boiler from a steam locomotive, two condensing coils, a

cooling box, and no less than thirteen 2,000-gallon fermenting vats. The

operation was large enough to meet the illegal whiskey needs of Baltimore,

Washington DC, and Philadelphia. It earned both it's eternal notoriety and

its demise during a tragic raid in July of 1929 that resulted in the murder

of a deputy sheriff. The

National Park Service has a well-detailed story at this location.

type

of still, with a boiler from a steam locomotive, two condensing coils, a

cooling box, and no less than thirteen 2,000-gallon fermenting vats. The

operation was large enough to meet the illegal whiskey needs of Baltimore,

Washington DC, and Philadelphia. It earned both it's eternal notoriety and

its demise during a tragic raid in July of 1929 that resulted in the murder

of a deputy sheriff. The

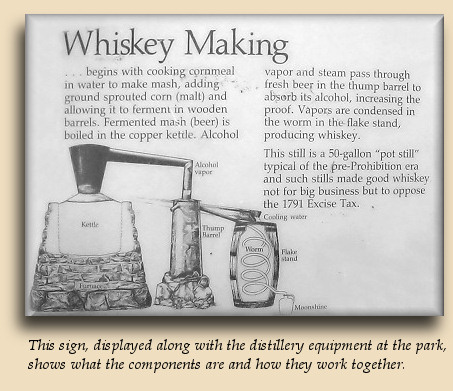

National Park Service has a well-detailed story at this location. Today, they only tell

stories, and even then, only occasionally. But at least they recognize the

existence of both whiskeymaking and moonshining and their importance to the

history of American people. The display, located outdoors in a natural

setting, has been put together quite nicely. The still itself is very

small, about a 50-gallon-capacity unit. It looks the way most people would

imagine a hillbilly moonshine still to look; what you might see in Li'l

Abner or on The Beverly Hillbillies. That's a far cry from the original Blue

Blazes, which looked like a train wreck and produced batches of 2,000

gallons at a time. The exhibit is really a better example of the sort of

personal still a 19th century farmer might have used as general farm

equipment, and that, rather than glorifying the actual Blue Blazes criminal

site, was probably their intent. As such, it's a very good display. We only

wish it were still huffing and puffing.

Today, they only tell

stories, and even then, only occasionally. But at least they recognize the

existence of both whiskeymaking and moonshining and their importance to the

history of American people. The display, located outdoors in a natural

setting, has been put together quite nicely. The still itself is very

small, about a 50-gallon-capacity unit. It looks the way most people would

imagine a hillbilly moonshine still to look; what you might see in Li'l

Abner or on The Beverly Hillbillies. That's a far cry from the original Blue

Blazes, which looked like a train wreck and produced batches of 2,000

gallons at a time. The exhibit is really a better example of the sort of

personal still a 19th century farmer might have used as general farm

equipment, and that, rather than glorifying the actual Blue Blazes criminal

site, was probably their intent. As such, it's a very good display. We only

wish it were still huffing and puffing. During that time, individual farm stills such as the one we see here at

Catoctin may have been operated illegally in the sense of being

unlicensed, but more and more distilling, even by small farmers, was being

done by larger (and licensed) distillers or as a service offered by the

grain mills. Thus, by 1802, when newly-elected president Thomas Jefferson

repealed the excise tax, most farmers were already enjoying the advantages

of patronizing commercial distillers and continued to favor using them.

During that time, individual farm stills such as the one we see here at

Catoctin may have been operated illegally in the sense of being

unlicensed, but more and more distilling, even by small farmers, was being

done by larger (and licensed) distillers or as a service offered by the

grain mills. Thus, by 1802, when newly-elected president Thomas Jefferson

repealed the excise tax, most farmers were already enjoying the advantages

of patronizing commercial distillers and continued to favor using them.