Israel Shreve's Distillery in

Perryopolis, Pennsylvania:

PERRYOPOLIS,

PENNSYLVANIA is a very small town which is just about as unique as

small towns get. Especially in Pennsylvania. For starters, there's that strange

name, Perryopolis. What kind of name is that for a little town? Well, it

isn't any stranger than Annapolis or Indiananapolis, or even Superman's

Metropolis; it simply means "city named after Perry". In this case, Admiral

Oliver Hazard Perry, hero of the Battle of Lake Erie in 1813. The town existed

long prior to that time, however. It was known as New Boston then, and was

laid out in a very precise manner, with wide streets arranged in a one-block

wide octangle in the center, itself centered on a monument circle such as

you might find at the entrance to a theme park. A block out from the octangle

is a concentric square formed by four streets, and another a block out from

that. Bisecting the corners of the squares are large diagonal streets that

end, as streets, at the octangle, but proceed as alleys to connect to the

area circling the monument. The rest of the town's streets are arranged in

a grid within this design. The blocks are not square but consist mostly of

two rows of properties, never more than four houses to a row, separated by

an alley. The whole effect is one of careful planning and is very different

from the more common Pennsylvania practice of having streets wind willy-nilly

with no discernible rhyme or reason. The layout was based on a plan

originally designed by a retired surveyor and Continental Army general named

George Washington, whose idea was that this community would become the capital

of the brand new United States of America. Yes, this is one of those places

where George Washington really did sleep. And he was certainly entitled to

sleep here... he had the title to prove it. Because in fact, he owned it.

The town was built on land that Washington had purchased when tracts of the

wilderness (which he had helped to obtain for Virginia in the 1750's) were

first offered for sale. He obtained 1,644 acres here and

in

1774 he built a grist mill. Or at least he started to build one. It was

delayed a few years while Washington was busy with another task...

founding our nation and managing the Revolutionary War. He never did operate

the mill; instead he leased the property to Col. Israel Shreve, a hero of

the war and a close personal friend. Like many grist mill owners, Shreve

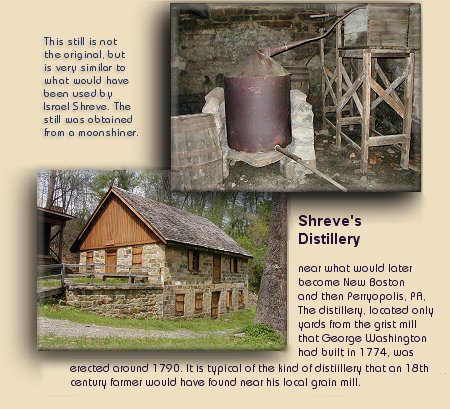

built a distillery next to the mill in 1790 and it's that distillery that

we are visiting today.

Perryopolis on a Thursday morning in May appears like a real, live version

of that little section of Lynchburg, Tennessee (pop. 361®)

where all the Jack Daniel's shops are. The central area seems about the size

of the "Main Street, USA" area of Disneyland/World. It looks a lot like it,

too, only cleaner. Across the wide street where we park, there's a man sitting

in front of the fire station talking to two buddies. He's holding a can for

fundraising donations, but other than us and two women walking toward a drugstore

the street is

empty.

The distillery, located only a few blocks from the center of town, is across

the road from the town park. There is a huge octagonal pavilion in the center

(the shape mirrors the center of the town layout) that was built a couple

years ago, but apparently they've added some new features this year (a performing

stage, we believe) and Perryopolians are very proud of it. The pavilion

was primarily funded with a donation from Dr. Harry Sampey, who grew up here

and wanted to give a part of his success back to the community. There is

a really good presentation showing the construction and dedication ceremonies

at

http://www.perryopolis.com/dedication1.shtml,

which is part of David Illig's great

Perryopolis website. The construction

was performed largely through donated work by local contractors and volunteer

work by local citizens, including John Martinak who, when he isn't installing

landscaping for the pavilion, serves as vice president of the Perryopolis

Area Heritage Society.

This morning, John is also serving as our personal tour guide. Although the

mill and distillery are technically open now, the tourist season really hasn't

started yet and there's still plenty left to do to get ready. The roadway

leading to the buildings needs work and the construction fence still surrounds

the site. Although the gate's not locked, it's only open a few inches and

the trail leading beyond is blocked by a pile of dead branches gathered up

from the winter storms.

After a long search among the numerous keys he carries, he finds the one

that will unlock the door to the grist mill. He also lets us into the distillery

and shows us the equipment inside. Shreve's was what we could call a first-level

commercial distillery. That is, it was a business enterprise that provided

a distilling service to people who brought their grain to the mill

to be processed. Except for possibly some local taverns and merchants, it

probably did not make much of its income from sales of the whiskey it produced.

A second-level commercial distillery, such as Abraham Overholt's Old Farm

distillery that we'll be visiting later, might also offer milling service,

but that would be an auxiliary income source. They would consider the grain

farmers to be their vendors rather than their primary customers, who would

be the purchasers of their finished whiskey.

The still that Shreve actually used has long ago vanished, but the one displayed

here is typical of the size and type that would have been here then. One

difference might be the quality and craftsmanship. The commercial still was

probably fashioned by a professional still maker or purchased from a still

company. Typical of the era, it would have been an ornate sculpture in copper

with every seam perfectly fitted. This still belonged to a moonshiner in

its previous assignment, and it's somewhat more crudely put together, most

likely due to its maker not exactly being a trained copper fitter.

The common distilleries of farmer/distillers would have been similar to Shreve's

in just about every way except that the building housing it would likely

have been smaller, unless the still were simply set up in a corner of the

barn. Stone is a very good material to build a distillery out of, by the

way. And having lots of windows is also a good idea. That's because it is

the nature of a distillery to set an open fire in the middle of an room filled

with containers of highly flammable alcohol and to produce even more of that

explosive substance in the form of vapor to fill up the enclosed space. It

would be a dangerous arrangement even if nothing leaked, and in reality

practically everything leaked.

Which is why Shreve's distillery has been restored at least twice. Earlier

descriptions of the restored distillery indicate that it was operational,

but any distilling that may have occurred there (only as a demonstration

for tourists, of course) ceased when the building was completely destroyed

by a fire in the 1970's, leaving only the original foundations. The Heritage

Society has restored the building again, using the original stones and the

building today looks just as it must have when it was a brand new, modern,

state-of-the-art distillery. They are doing the same for the grist mill,

which is also being restored to it's original condition.

Or at least more or less its original condition. John tells us that hasn't

been all that easy to do. As we explore the mill, for example, John shows

us the nifty emergency backup electric system they were required to install,

since this is a public building, in case the mainline electricity fails.

Nice idea; only problem is, the original mill didn't have electricity, of

course.

Well, George Washington never completed (nor even started) his vision for

the United States' capital here at New Boston. Philadelphia and New York

would have to serve that purpose until a new federal city in a new federal

district could be built. A city with streets that run diagonally and converge

much the same as those of Perryopolis do. And it's doubtful that any of

Perryopolis' 1,833 current residents feels even the slightest regret that

there's no Capital Beltway around their lovely town.

American Whiskey:

George Washington Slept

Here in 17??...

We

visit in May 2003

![]()

We half expected to meet Sheriff Taylor and Barnie Fyffe as we walk toward

the community offices to find out where the Shreve Distillery is.

We half expected to meet Sheriff Taylor and Barnie Fyffe as we walk toward

the community offices to find out where the Shreve Distillery is.

To get to the distillery we must

shuffle down the hill by way of a short but steep path. As we begin poking

around the locked building, John drives up in his truck. We didn't ask, but

the nice lady at the community office probably called him when we said we

were going to be looking at the buildings and he interrupted whatever he

was doing to come show us around.

To get to the distillery we must

shuffle down the hill by way of a short but steep path. As we begin poking

around the locked building, John drives up in his truck. We didn't ask, but

the nice lady at the community office probably called him when we said we

were going to be looking at the buildings and he interrupted whatever he

was doing to come show us around.

And

it wasn't the Heritage Society's intent to include electricity in the

restoration, either. In order to comply with modern codes, however, the restorers

had to run an electric service line out to the building in order to support

the required emergency backup system, which cannot pass its certification

tests without an electric circuit to back up. So they installed a service

entry, a circuit panel, and a single circuit supporting one lamp just so

the backup system can protect it and comply with code.

And

it wasn't the Heritage Society's intent to include electricity in the

restoration, either. In order to comply with modern codes, however, the restorers

had to run an electric service line out to the building in order to support

the required emergency backup system, which cannot pass its certification

tests without an electric circuit to back up. So they installed a service

entry, a circuit panel, and a single circuit supporting one lamp just so

the backup system can protect it and comply with code.

Next Stop ----------- The Whiskey

Rebellion