| American Whiskey The Rebellion They Blamed on Whiskey |

Pockets, but no Sixpence...

|

|

IN

1776, REPRESENTATIVES of the thirteen British colonies in America

had agreed to become allies in what was, at the time, one of the boldest

and most awesome political events ever undertaken. For the first time ever,

the common citizens occupying colonies of an imperial world power would undertake

to announce their independence and declare themselves to be sovereign nations. IN

1776, REPRESENTATIVES of the thirteen British colonies in America

had agreed to become allies in what was, at the time, one of the boldest

and most awesome political events ever undertaken. For the first time ever,

the common citizens occupying colonies of an imperial world power would undertake

to announce their independence and declare themselves to be sovereign nations.

The

ensuing warfare lasted for eight years and forever changed the history of

the world. When the bullets stopped flying, there were thirteen fiercely

independent nations loosely allied to one another. The

ensuing warfare lasted for eight years and forever changed the history of

the world. When the bullets stopped flying, there were thirteen fiercely

independent nations loosely allied to one another.

As colonies, they hadn't been encouraged to interact much. The Empire preferred that each colony trade only with Britain and that each would remain dependent upon that arrangement. So now that they had achieved political independence, they often found themselves stumbling over their carefully-conditioned social independence. The new states really didn't trust each other very much and cooperative ventures were often bogged down by the need to establish a hierarchy acceptable to everyone. Many, if not most, of the educated leaders were quite content to have replaced the British Crown with their own organizations and, although quick to acknowledge appreciation for the help of their co-revolutionary colleagues, saw no reason to make any further concessions to them now that independence had been accomplished. And rank-and-file farmers and shopkeepers and craftsmen who made up the bulk of the population returned from the Revolutionary War to their farms and shops, rejoicing that they had thrown off the yoke of political repression forever. The "Great American Dream" of the late 18th century was the abolition of all government, save that of your local church and maybe, on rare occasion, a need for laws made at the county level.

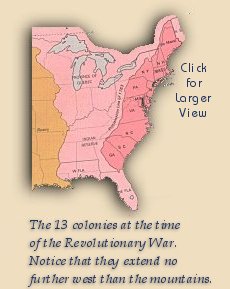

But the thirteen new American states weren't the only kids on the block.

For one thing, there were the people who used to live here. Most of them

had moved west and now inhabited the huge area from the mountains to the

Mississippi river. Which is where the British wanted them. But that was now

our own back yard and there was a lot of pressure to expand into it.

Meanwhile the French were setting up military forts to defend their claims from Indians... and from Virginians, too. And right behind them, on the other side of the Mississippi, were the Spanish. Spain had long ago ceded its Atlantic seaboard possessions to England. Their interest in the New World was their search for gold, and they had no desire to be involved in colonizing the east coast. But that was when Britain owned it. These newly independent countries would be very easy to overcome. And of course, there was still the British Empire. The American colonies had not really been all that high on Britain's priority list at the time of the revolution. As defense of their interests there began to require some effort (that is, money), and certainly once the Spanish and later the French had joined in, they found they had more important issues against which to direct their limited resources. But now that the fight appeared to be over, the continuing sting of the Empire's black eye would almost certainly require a rematch. And the individual American nations could easily be picked off one by one this time. There were Americans who thought differently. Between 1784 and 1789 the men who would become known as the Founding Fathers struggled to convince the provincial state governments (and their own colleagues) that Americans desperately needed a single, combined federal government. That the alliance between the thirteen united states needed to become a single nation, the United States of America. And that the power and authority of the United States must be understood to take precedence over any such claim by any individual state. One nation. With Liberty and Justice for all. Nice words, but not everyone agreed with them. For example, in western Pennsylvania there was very little of what the eastern Americans called "money". There weren't any banks. And there certainly weren't any ATM machines. People exchanged goods and services by barter, and with little agreement on what tradable items were worth. That was because most tradable items were perishable. Whiskey was different. Properly stored, such as in a warehouse, whiskey lasted forever. Or close enough, anyway. A barrel of whiskey had a certain value and that could be banked on. You didn't need to actually carry a jug around with you, dispensing out some to the barber and some to the dry-goods merchant and so forth. If you had two barrels of whiskey stored at Col. Shreve's warehouse, for example, you could write what amounted to a check against a portion of that and use that check the same as we do with cash issued by the United States. The barber or storekeeper didn't need to cash your check in for whiskey, either. He could re-spend it or combine it with the notes of others, at least for local purchases.

In ordinary times, and considering how little attention the western frontier

drew from the powerful coastal states, that was perfectly acceptable to everyone.

George Washington was president of that federalist country, and he chose

to pay the folks living on and around his old property a little visit. Just

to remind them that we're all in this together and that they should work

to help make our country strong instead of entertaining such destructive

thoughts. To help him make his point clear, he brought along a few friends

-- about 13,000 of them, armed to the teeth with the best weapons that

excise-tax-raised money could buy.

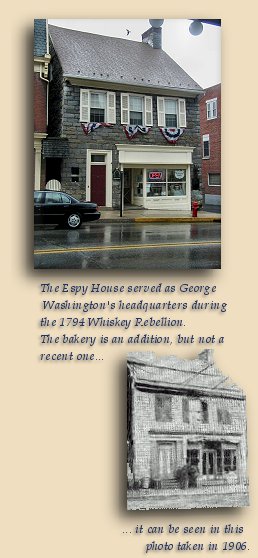

Would you like to own a piece of authentic American history? Would you like to know that George Washington really did stay in your home? Would you like the cashflow from two apartments upstairs (1300 and 1650 square feet) and the bakery downstairs? Would you like to sip fine rye whiskey with other residents of one of America's most historic communities? If you're interested, the Espy House is for sale (at least it is as of our visit here in May 2003). Asking price is surprisingly low -- we have tract homes in our town that sell for a lot more. Check out this site http://www.theespyhouse.com/realestate.htm , it's really not a joke. Normally we can expect rain every time we take a vacation and this one is no exception. Actually, the weather has been beautiful the whole time; this morning is the only exception. But it's certainly a first-rate exception. Not only is it raining steadily on a morning filled with walking from place to place (mostly antique stores), but it's COLD. More like February than spring. It's early May and we're supposed to be enjoying the floral results of April showers, not being wet and uncomfortable. At least the photographs look better on days like this. John stands under a dripping awning and gets this picture of the Espy House. He also gets a stream of runoff rainwater down his back. While searching the internet for information later we'll find another photo taken from the exact same spot. In the sunshine. Ours looks better. John finds a dry shirt in the trunk.

It's still raining when we get to the

Jean Bonnet Tavern. Raining

hard. Which is why you see a stock photo from their brochure here. We had

wanted to stop and have lunch at this lovely old Pennsylvania tavern because

it was a focal point of the Whiskey Rebellion. Actually, we had wanted to

have dinner here last night, but we took the slow and scenic route from Maryland

and by the time we got to Bedford it was too late for dinner anywhere but

Hardee's drive-thru.

The reason we are so fascinated with the Whiskey Rebellion and those times is that we feel that one incident, perhaps even more than the Revolutionary War itself, marked the point where the United States of America became a reality. We live near Dayton, Ohio, home of Wilbur and Orville Wright. The heavier-than-air "airplane" was conceived, designed, invented, and built in Dayton... but mankind first truly accomplished flight at the Wright family's summer home on the beach in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, because that's where they put their airplane to the test and that's where it flew. In 1794 George Washington, while staying at Dave Espy's house in Bedford, was informed that he had succeeded in intimidating the citizens of western Pennsylvania into submission to the sovereignty of the federal government. Equally important was the fact that the soldiers were from several states, a coalition army demonstrating obedience to a national purpose. Without a solid central government to tie the states into a single, formidable nation, foreign interests would take out the individual states one by one, and those foreign interests were watching. Until this confrontation no one really knew if the federal government would prevail. It was the test of all that George Washington had dedicated his life for, and like the Wright brothers' airplane, it flew. There really was a United States of America. The army went on to arrest some of the insurgent leaders and took them to Philadelphia for trial, but all were pardoned. Others fled to Spanish Louisiana and English Ontario. The point had been well taken and that would be the end of the story... for another three score and seven years anyway. |

|

|

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2003 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|

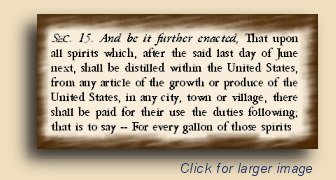

Others believe the excise tax was levied in order to raise money to pay off

the interest on the Revolutionary War debt, and they're much closer

to the truth, because that reason is specified in the text of the law itself.

But many people then, and quite a few today, believe there was more to it

than that. The less-educated may have become violently upset to see the new

federal government using the same tactics they put their lives on the line

to overthrow, but the more learned citizens understood that the tax's real

purpose was to destroy the use of whiskey as a locally-created currency and

producer of wealth. It was an open declaration by the federal government

that it was in charge and would tolerate neither political nor economic

independence among the individual states. The reaction in the western counties

of Kentucky, Tennessee, Pennsylvania and Virginia was predictable... they

simply ignored it.

Others believe the excise tax was levied in order to raise money to pay off

the interest on the Revolutionary War debt, and they're much closer

to the truth, because that reason is specified in the text of the law itself.

But many people then, and quite a few today, believe there was more to it

than that. The less-educated may have become violently upset to see the new

federal government using the same tactics they put their lives on the line

to overthrow, but the more learned citizens understood that the tax's real

purpose was to destroy the use of whiskey as a locally-created currency and

producer of wealth. It was an open declaration by the federal government

that it was in charge and would tolerate neither political nor economic

independence among the individual states. The reaction in the western counties

of Kentucky, Tennessee, Pennsylvania and Virginia was predictable... they

simply ignored it.

The

next step was for the federal government to become more demanding, singling

out the most readily-accessible of the disobedient areas, the western

Pennsylvania counties of Fayette, Westmoreland, Allegheny, and Washington.

And when the local courts refused to enforce the federal law, United States

treasurer Alexander Hamilton knew he had a problem that required immediate

attention. By 1794 western Pennsylvania was ready to pull out of the union.

The farmers, who had already gotten physical with some tax collectors and

had taken that anger out on public and private property, were ready to march

on Pittsburgh with pitchforks and squirrel rifles. And legislators and

justices were ready to consider alliances with Britain or Spain as an alternative

to any further association with the hated federalists.

The

next step was for the federal government to become more demanding, singling

out the most readily-accessible of the disobedient areas, the western

Pennsylvania counties of Fayette, Westmoreland, Allegheny, and Washington.

And when the local courts refused to enforce the federal law, United States

treasurer Alexander Hamilton knew he had a problem that required immediate

attention. By 1794 western Pennsylvania was ready to pull out of the union.

The farmers, who had already gotten physical with some tax collectors and

had taken that anger out on public and private property, were ready to march

on Pittsburgh with pitchforks and squirrel rifles. And legislators and

justices were ready to consider alliances with Britain or Spain as an alternative

to any further association with the hated federalists.

With

Washington leading (the only time an acting American president has ever lead

an army into battle), this militia numbering more soldiers than was needed

to fight the Revolutionary War marched west across Pennsylvania. Through

Harrisburg they marched, and through Carlisle, all the while sending out

messengers with deals and threats to try and prevent a bloody confrontation.

They reached Bedford and the Allegheny Mountains and stayed there while

Washington set up command in the home of Colonel David Espy. The Espy House,

as it was known then and now, was built around 1766 and is the oldest building

in Bedford. The town sort of grew up around it. It's a two-story house and

still in use, with living quarters upstairs and most of the ground floor

taken up by the aptly-named Washington Bakery. The bakery has been there

since before 1906.

With

Washington leading (the only time an acting American president has ever lead

an army into battle), this militia numbering more soldiers than was needed

to fight the Revolutionary War marched west across Pennsylvania. Through

Harrisburg they marched, and through Carlisle, all the while sending out

messengers with deals and threats to try and prevent a bloody confrontation.

They reached Bedford and the Allegheny Mountains and stayed there while

Washington set up command in the home of Colonel David Espy. The Espy House,

as it was known then and now, was built around 1766 and is the oldest building

in Bedford. The town sort of grew up around it. It's a two-story house and

still in use, with living quarters upstairs and most of the ground floor

taken up by the aptly-named Washington Bakery. The bakery has been there

since before 1906.