Button up your Overholt, when the wind blows free...

Summer of 2003

IF YOU BEGIN reading about

the origins of bourbon whiskey, you

will soon encounter the story of how the Whiskey Rebellion drove Pennsylvania

distillers down the Ohio river and into Kentucky. This is often cited as

the beginnings of what would become the great Kentucky Bourbon industry.

It's a nice story, but probably not true. For one thing, as our historian

friend Michael Veach points out, not a single one of Kentucky's grand old

bourbon whiskey families came there by that route. For another, the Whiskey

Rebellion took place in the early 1790's, by which time Kentucky farmers

had been making whiskey out of corn for nearly fifty years. The migration

of displaced Pennsylvanians certainly can't be credited with the introduction

of distilling to the area.

The newly

arrived were nearly all individual farmers who distilled for their own

consumption, not commercial distillers.

The newly

arrived were nearly all individual farmers who distilled for their own

consumption, not commercial distillers.

Besides, the Whiskey Rebellion didn't really have as disastrous an effect on Monongahela as is often portrayed. It could be argued, in fact, that it was the best thing to happen to American whiskey since the Revolutionary War popularized the substitution of American products for such "loyalist" items as tea and rum. The imposition of the excise tax may have made distilling prohibitive to some individual farmers, but for the commercial distiller the result was the elimination of an entire class of competition, and at a cost that could be simply added as an expense to the final price. What's more the expense was borne equally among them, so for all the public howling and wailing, in the end the commercial blow of the tax was virtually non-existent.

In fact, almost immediately after the hostilities had ended, the distilling industry in Pennsylvania began a boom that brought it to world-class proportions and kept it there throughout the century. As an example, the cost of the Whiskey Rebellion to the United States federal government was $669,992, a very formidable amount at that time. In 1885 the Gibson Distilling Company alone paid $675,000 in federal taxes. We've already visited an example of the first level of commercial distilling at Israel Shreve's mill in Perryopolis. Such distilleries were similar to what a prosperous farmer might have for his own use, but would be operated in conjunction with a grist mill as a service for its customers. As the distillery became more successful it might eventually reach the point where it would be practical to reduce or eliminate contract work and begin distilling full-time in support of its own product.

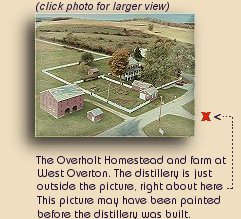

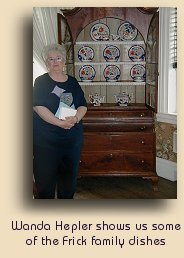

Around 1810, Abraham Overholt and his brother Christian began to do just that at their family's farm in Westmoreland county. And we're on our way this morning through the beautiful rolling Pennsylvania countryside to meet with Wanda Hepler of the West Overton Museum staff who has graciously taken a big chunk out her busy pre-season preparation schedule to introduce us personally to the homestead.

In 1800, Henry Overholtzer (1739-1813), his family, and many of his friends migrated west from Bucks county, on the eastern edge of the state, and settled in Westmoreland county, near the western edge. Henry's branch of the Oberholtzer family were called Oberhold, and they were neighbors of ours... a little over two hundred years ago. There are Oberholtzers, Oberholds, and Overholts spread all over the part of Bucks county where we lived until the mid-1990s. And they were just as prominent in the mid 1790s. They lived (and many of their descendants still do) in Bedminster, Plumsteadville, Deep Run, Blooming Glen, Perkasie, Dublin, and all around our old Hilltown neighborhood. Several had mills and distilleries, so we're not sure just where Henry lived, but we think it might have been very close. Jacob Beidler, who lived with his wife Annie (Lederach) in Hilltown and who died in 1781 named Henry Oberholtzer and Henry Rickert executors of his estate. Our home on the pike between Hilltown and Line Lexington was built in the late 1750s, and would have been well-known to them. Rickert Road, about a mile from Linda's family home near Dublin, probably led to Henry Rickert's farm. The Lederachs lived only a few miles west, in Montgomery county.

Of course none of our relatives lived there at that time, but that minor detail doesn't affect our sense of kinship as we drive through the clean morning air toward Scottdale.

We awoke this morning in Greensburg. Which isn't surprising, considering that we went to sleep there. But then that was only a few hours earlier this morning, after arriving at our motel very late at night in the rain. This morning is bright and clear (even if we're not yet) and the Overholt homestead is just a short ride away.

Henry O and his group probably also stayed in Greensburg the day before they arrived at their new home. We know that they came across Pennsylvania along the road that is now Route 30 (the Lincoln Highway), because that's the only road there was then. Greensburg was a major settlement and crossroads on that highway, and they would have taken the road from there toward Uniontown. About twenty miles south of Greensburg, or a day's journey by wagon, sets us right at the homestead, as it probably did them. For us it was a lot quicker and easier, and included stopping for breakfast at the New Stanton Cracker Barrel.

We are visiting the birthplace of a brand of rye whiskey whose life spans

nearly the whole range of Monongahela history and is still commonly available

today. In fact, for many Americans Old Overholt is the only real rye whiskey

they've ever seen.

The whiskey has changed

considerably, though the label has remained remarkably consistent over the

years. But we'll cover Old Overholt in more detail later, because that whiskey

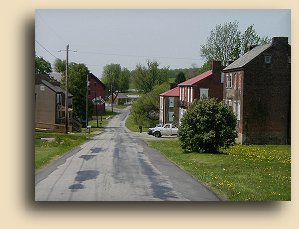

came a generation later. Near Scottdale we drive down a narrow road leading

past a small group of old empty houses, the ghost village of West Overton.

The whiskey has changed

considerably, though the label has remained remarkably consistent over the

years. But we'll cover Old Overholt in more detail later, because that whiskey

came a generation later. Near Scottdale we drive down a narrow road leading

past a small group of old empty houses, the ghost village of West Overton.

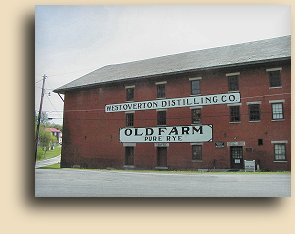

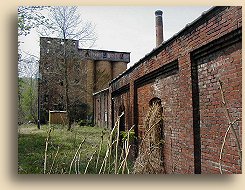

That story comes later, too. For as we come to the bottom of the hill we see before us the huge red brick building that once held the Overholt family distillery and warehouse.

And painted on the side in big black letters on a white background is the name of the whiskey made here, not "Old Overholt" but "WEST OVERTON DISTILLING CO. - OLD FARM - PURE RYE".

There's nothing left of the distillery equipment anymore; the building now

houses the West Overton Museum. But the museum is filled with fascinating

exhibits. The story of this homestead goes well beyond Abraham Overholt's

distillery and the museum covers the transformation of western Pennsylvania

from an agrarian to an industrial (especially coal, coke, and steel) economy.

In addition to several cases of whiskey- and distillery-related items there

is farm equipment, pottery, exhibits about the coke and coal industry, and

of course much Henry Clay Frick memorabilia.

The

museum, funded by a grant from Henry Clay Frick's daughter Helen, is mainly

oriented toward preserving and displaying artifacts about the homestead because

this was his birthplace and his home for the first third of his life, although

one would never grasp that from any biography ever written about him. H.

Clay Frick was one of the founding figures of the Great Industrial Age, along

with Andrew Carnegie and Andrew Mellon. He was a union-buster who once held

the title of "America's most hated man". He was a world-renowned art collector

and patron, and a philanthropist who donated millions of dollars to charity.

He was one of Pittsburgh's most famous citizens.

The

museum, funded by a grant from Henry Clay Frick's daughter Helen, is mainly

oriented toward preserving and displaying artifacts about the homestead because

this was his birthplace and his home for the first third of his life, although

one would never grasp that from any biography ever written about him. H.

Clay Frick was one of the founding figures of the Great Industrial Age, along

with Andrew Carnegie and Andrew Mellon. He was a union-buster who once held

the title of "America's most hated man". He was a world-renowned art collector

and patron, and a philanthropist who donated millions of dollars to charity.

He was one of Pittsburgh's most famous citizens.

His father, John W. Frick was

a farm worker described as "impecunious", "unambitious", "unimpressive".

His mother was Abraham and Maria Overholt's daughter Elizabeth, and the family

was living in the spring house here at her parents' farm when Clay was born.

He grew up on this farm, and his formative years were spent here. He obtained

the business skills that would make him a millionaire at thirty by working

with, or upon recommendation of, various family members (quite a lot of them,

as matter of fact; Clay apparently couldn't hold a job very long; what he

seemed best at was long periods of being doted on by his mother and grandmother

while back at the homestead recuperating from illness). At sixteen he went

to work for his uncle, as a clerk. He remained in that job for three years

and when he was abruptly fired his cousin Abraham Overholt Tinstman, a partner

in the Broad Ford distillery at the time, hired him as an office boy for

$25 a month. Although Clay Frick is credited in the biographies as having

the business sense to make a fortune on coke and coal, it was really Cousin

Abe Tinstman's ventures into those areas, especially the Morgan Mining Company,

that brought Frick into it. He worked closely with his cousin in several

ventures over the next ten years, including the Mt. Pleasant & Broad

Ford Railroad.

His father, John W. Frick was

a farm worker described as "impecunious", "unambitious", "unimpressive".

His mother was Abraham and Maria Overholt's daughter Elizabeth, and the family

was living in the spring house here at her parents' farm when Clay was born.

He grew up on this farm, and his formative years were spent here. He obtained

the business skills that would make him a millionaire at thirty by working

with, or upon recommendation of, various family members (quite a lot of them,

as matter of fact; Clay apparently couldn't hold a job very long; what he

seemed best at was long periods of being doted on by his mother and grandmother

while back at the homestead recuperating from illness). At sixteen he went

to work for his uncle, as a clerk. He remained in that job for three years

and when he was abruptly fired his cousin Abraham Overholt Tinstman, a partner

in the Broad Ford distillery at the time, hired him as an office boy for

$25 a month. Although Clay Frick is credited in the biographies as having

the business sense to make a fortune on coke and coal, it was really Cousin

Abe Tinstman's ventures into those areas, especially the Morgan Mining Company,

that brought Frick into it. He worked closely with his cousin in several

ventures over the next ten years, including the Mt. Pleasant & Broad

Ford Railroad.

You'll find little about this in any of the

biographies, either. Nor about how, when his cousin's investments were completely

wiped out in the Panic of 1873 and he was trying to fight his way back from

near-bankruptcy, Henry Clay "helped" by secretly purchasing options from

the railroad shareowners and selling A.O.'s railroad out from under him.

You'll find little about this in any of the

biographies, either. Nor about how, when his cousin's investments were completely

wiped out in the Panic of 1873 and he was trying to fight his way back from

near-bankruptcy, Henry Clay "helped" by secretly purchasing options from

the railroad shareowners and selling A.O.'s railroad out from under him.

The

railroad sold for $200,000 to the Baltimore & Ohio, which covered the

costs, with no profit. Henry, however earned $50,000 in personal commissions.

Three years later, holding a note for $60,000 against his cousin's Morgan

Mines, Frick foreclosed and took ownership. Two years after that he reached

his goal of becoming worth one million dollars.

The

railroad sold for $200,000 to the Baltimore & Ohio, which covered the

costs, with no profit. Henry, however earned $50,000 in personal commissions.

Three years later, holding a note for $60,000 against his cousin's Morgan

Mines, Frick foreclosed and took ownership. Two years after that he reached

his goal of becoming worth one million dollars.

Certainly a fascinating person, and it is around Frick's career that the museum is really focused. That it was also the home of the Overholt family and of the important brand of whiskey they made is only a side interest. Oh yes, one other thing... Henry Clay Frick, who died in 1919 -- the year that the 18th Amendment brought national prohibition and the end of the whiskey industry as it had been -- also happened to be the last Overholt family member to own "A. Overholt & Co".

The museum also contains several spinning wheels and weaving looms, and an

extensive collection of quilts and woven goods, some dating back to the time

when a thriving weaving business was being conducted here by a young man

in his early twenties, Abraham Overholt, son of Henry and Anna of Bucks county.

Abraham was sixteen when his family arrived here, and grew to be a master

weaver. In 1810 he and his brother Christian presented a novel suggestion

to the family --

that

the very same whiskey they'd always distilled for personal use and minor

barter could provide an acceptable income if made in sufficient quantities

to sell commercially. This transformation from home-made to commercial status

was just beginning to occur throughout western Pennsylvania, and was

at least partly the result of the dreaded federal excise tax. The idea

was that if you're going to have to pay money for something you might as

well sell it and get back all the money you paid for taxes and enough more

as profit to make the whole enterprise worthwhile.. Especially if your facility

were large enough to produce a substantial amount for sale. As a family farm,

the Overholts were capable of distilling about six to eight gallons a day.

Abraham and Christian rebuilt the distillery and increased the capacity to

nearly 200 gallons a day. They called their whiskey "Old Farm". Abraham later

bought out his brother's share of the business and, in the mid-1800s, went

into partnership with two of his sons, one of whom would later build a new

distillery a few miles away at Broad Ford.

that

the very same whiskey they'd always distilled for personal use and minor

barter could provide an acceptable income if made in sufficient quantities

to sell commercially. This transformation from home-made to commercial status

was just beginning to occur throughout western Pennsylvania, and was

at least partly the result of the dreaded federal excise tax. The idea

was that if you're going to have to pay money for something you might as

well sell it and get back all the money you paid for taxes and enough more

as profit to make the whole enterprise worthwhile.. Especially if your facility

were large enough to produce a substantial amount for sale. As a family farm,

the Overholts were capable of distilling about six to eight gallons a day.

Abraham and Christian rebuilt the distillery and increased the capacity to

nearly 200 gallons a day. They called their whiskey "Old Farm". Abraham later

bought out his brother's share of the business and, in the mid-1800s, went

into partnership with two of his sons, one of whom would later build a new

distillery a few miles away at Broad Ford.

We will visit Broad Ford later today. Right now we're sitting in the kitchen

of the lovely old homestead building, listening as our hostess Wanda tells

fascinating stories of the Overholts and Fricks and Stauffers, and Mellons

and so forth. A few weeks ago, John had called the West Overton Museum in

the hope that we might get a chance to see inside the distillery building,

despite the fact that officially they wouldn't be open for the season yet.

He spoke to Laverne Love, who in turn made arrangements with Wanda Hepler,

who has not only let us in but is spending much of her busy morning visiting

with us.

She

has shown us the home and the exhibits in the museum, and we've learned about

George Washington, and the French-Indian War, and Fort Duquesne, and the

Whiskey Rebellion, and more in a fascinating presentation which consists

of an audio tape, recorded by the president of the historical society, and

keyed to the historic events pictured on an intricate four-wall mural surrounding

us as we sit in the parlor. We are now sitting around a formica-topped table

in the kitchen, which, with running water, a coffeemaker, and a microwave,

is the only non-period room in the house. It's also mission-control central

for the project of readying the place for the tourist season, so it has

time-charts and planning calendars posted, along with bottles of 150-year-old

whiskey. Wanda is telling us about the empty houses in the ghost town we

passed through up the street. We've actually brought along a cherished bottle

containing Old Overholt whiskey made in 1934, but she politely declines to

sample it.

She

has shown us the home and the exhibits in the museum, and we've learned about

George Washington, and the French-Indian War, and Fort Duquesne, and the

Whiskey Rebellion, and more in a fascinating presentation which consists

of an audio tape, recorded by the president of the historical society, and

keyed to the historic events pictured on an intricate four-wall mural surrounding

us as we sit in the parlor. We are now sitting around a formica-topped table

in the kitchen, which, with running water, a coffeemaker, and a microwave,

is the only non-period room in the house. It's also mission-control central

for the project of readying the place for the tourist season, so it has

time-charts and planning calendars posted, along with bottles of 150-year-old

whiskey. Wanda is telling us about the empty houses in the ghost town we

passed through up the street. We've actually brought along a cherished bottle

containing Old Overholt whiskey made in 1934, but she politely declines to

sample it.

Although the property included a mill, it was the fulling mill from Abraham's earlier career in weaving. Grain for the distillery had to be taken to nearby Jacob's Creek to be ground. "Nearby" is a relative word. The town of Scottdale, on Jacob's Creek, is only a few minutes away today. It wasn't even thought of as very far in 1830. But when you're struggling to get a team of stubborn oxen to pull a wagonload of your livelihood's precious raw materials through two feet of mud, or waiting for days until a wheelwright can get out to where you're broken down, "nearby" can quickly come to mean "too far". In 1834 Abraham built a brick flour mill adjacent to the distillery.

The cycle had gone all the way around -- the early days of commercial whiskeymaking saw distilling as a side business and service offered to customers of the grain mills. Col. Shreve's distillery in Perryopolis was a good example of that. And now we have Abraham Overholt building a grain mill for his distillery, and offering a flour-milling service to neighboring farmers as an added feature.

By the mid-1850s Abraham

had brought his sons Jacob and Henry into the business and the company was

also operating a much larger distillery at Broad Ford, which we will visit

later today. The whiskey they made there was not Old Farm, which continued

to be a successful brand, and by 1859 the facilities at the West Overton

site had become inadequate to support the brand's success. That year they

completely demolished both the distillery and the mill, and built an all-new

six-story brick building that housed both the new distillery and the mill.

That was over 140 years ago, and is the building we see today.

By the mid-1850s Abraham

had brought his sons Jacob and Henry into the business and the company was

also operating a much larger distillery at Broad Ford, which we will visit

later today. The whiskey they made there was not Old Farm, which continued

to be a successful brand, and by 1859 the facilities at the West Overton

site had become inadequate to support the brand's success. That year they

completely demolished both the distillery and the mill, and built an all-new

six-story brick building that housed both the new distillery and the mill.

That was over 140 years ago, and is the building we see today.

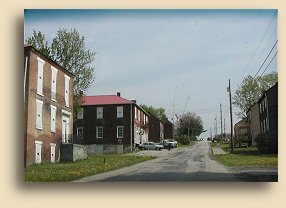

The abandoned houses leading up the road are what's left of the town of West

Overton. The buildings once housed distillery workers and the stores and

services they needed. It was also the Overholt family's (and A. Overholt

& Co.'s) official place of residence for a hundred years. When

Prohibition closed the distillery in 1919 West Overton had no other source

of employment to offer and was abandoned. Of course most of the buildings

are forever gone, but surprisingly several remain. That's because the buildings

Overholt built for its employees, like nearly everything else they built,

were constructed of brick. And also because, in 1922, Henry Clay Frick's

only daughter (and Abraham's great granddaughter) Helen Clay Frick began

to purchase the buildings in West Overton where her father was born. In 1928,

Helen Frick founded the Westmoreland-Fayette Historical Society to operate

and maintain the site, which became known as the West Overton Museums.

Restoration of the home and farm has been the first priority, of course,

and it's an ongoing task, lovingly performed by such members of the Society

as Wanda and Laverne, and executive director Rodney Sturtz.

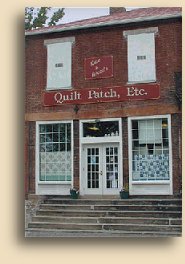

Recently however, more attention

has been turned toward developing the Village part of West Overton Village.

The idea is to eventually restore all the buildings to original, or at least

"quaint shoppe", condition and thus increase the scope of the attraction.

There are already a couple of craft shops operating, including

Kate & Becca's Quilt Patch

Etc., which occupies the home where Abraham's brother Christian operated

the Christian Overholt Emporium, a general store selling dry-goods, groceries,

hardware, clothes, and just about everything else. Since the building is

also identified as the C.S. Overholt House, we believe that Abraham's son,

Christian Stauffer Overholt, lived here. Christian S. lived in West Overton

until he was 45, which is around the same time his uncle died, so either

or both could have lived in the house. It's also possible that neither lived

there, but that the elder Christian may have willed the Emporium store and

the building to his nephew. Helen Clay Frick's father was born in the springhouse

on the Overholt farm, and his first job as a young man was working in Christian's

Emporium.

Recently however, more attention

has been turned toward developing the Village part of West Overton Village.

The idea is to eventually restore all the buildings to original, or at least

"quaint shoppe", condition and thus increase the scope of the attraction.

There are already a couple of craft shops operating, including

Kate & Becca's Quilt Patch

Etc., which occupies the home where Abraham's brother Christian operated

the Christian Overholt Emporium, a general store selling dry-goods, groceries,

hardware, clothes, and just about everything else. Since the building is

also identified as the C.S. Overholt House, we believe that Abraham's son,

Christian Stauffer Overholt, lived here. Christian S. lived in West Overton

until he was 45, which is around the same time his uncle died, so either

or both could have lived in the house. It's also possible that neither lived

there, but that the elder Christian may have willed the Emporium store and

the building to his nephew. Helen Clay Frick's father was born in the springhouse

on the Overholt farm, and his first job as a young man was working in Christian's

Emporium.

As we leave we notice there is quite a bit of construction activity going on at other buildings as well. The reason Rodney and Laverne couldn't be here to host us themselves is that they are leading a busload of guests on a four-day excursion to Colonial Williamsburg. At least one purpose for the trip is to gather ideas and information, because the Historical Society would like to develop West Overton Village along similar lines.

Helen Clay Frick, who lived

until 1984, was an unusual woman who (like her father) had her personal checks

imprinted with a photograph of her older sister who died when Helen was three.

She never married, instead dedicating her life to becoming her father's constant

companion, confidante, and protector.

He

died in 1919, when she just thirty-one, and she spent the rest of a long

life (she lived to be 96) glorifying his legacy through grants, foundations,

and museums. Included in this quest was the purchase of all the old abandoned

buildings of West Overton. The relationships within the Frick family are

worthy of study all by themselves and researching has been difficult and

fascinating. The relationships between the Fricks and the Overholts is even

more intriguing, but that will have to wait for another time. For the moment,

we would like to thank Helen for providing a means to better understand,

not her father or even the American Industrial Age with which he became so

identified, but rather his grandfather and the origins of one of our favorite

subjects. In her honor (and her father's) we raise a (small, because it's

very precious) glass of... Hah! I'll bet you thought we were going

to say, "Old Overholt", but we're not. The Old Overholt we have is indeed

from a bygone era, but it's not bygone enough for this toast. We also have

a bottle containing "Mount Vernon Pure Rye Whiskey". Despite the name, it

wasn't really made by George Washington at Mount Vernon; it was made in

Pennsylvania and bottled by the Cook & Bernheimer Company of Philadelphia...

in 1914. So this whiskey (which is delicious -- not like the horribly overaged

medicinal whiskey from the Prohibition years) was bottled while Henry Clay

Frick was still alive and when Helen was the same age (twenty-six) Abraham

Overholt was when he started the whole business.

He

died in 1919, when she just thirty-one, and she spent the rest of a long

life (she lived to be 96) glorifying his legacy through grants, foundations,

and museums. Included in this quest was the purchase of all the old abandoned

buildings of West Overton. The relationships within the Frick family are

worthy of study all by themselves and researching has been difficult and

fascinating. The relationships between the Fricks and the Overholts is even

more intriguing, but that will have to wait for another time. For the moment,

we would like to thank Helen for providing a means to better understand,

not her father or even the American Industrial Age with which he became so

identified, but rather his grandfather and the origins of one of our favorite

subjects. In her honor (and her father's) we raise a (small, because it's

very precious) glass of... Hah! I'll bet you thought we were going

to say, "Old Overholt", but we're not. The Old Overholt we have is indeed

from a bygone era, but it's not bygone enough for this toast. We also have

a bottle containing "Mount Vernon Pure Rye Whiskey". Despite the name, it

wasn't really made by George Washington at Mount Vernon; it was made in

Pennsylvania and bottled by the Cook & Bernheimer Company of Philadelphia...

in 1914. So this whiskey (which is delicious -- not like the horribly overaged

medicinal whiskey from the Prohibition years) was bottled while Henry Clay

Frick was still alive and when Helen was the same age (twenty-six) Abraham

Overholt was when he started the whole business.

Our toast of Old Overholt (made in 1934 and bottled in 1941) we raise to Karen Rose Overholt Critchfield who, in 1984, began a quest to learn everything she could about her ancestors, the Overholts who lived here. They were a family with at least as many twists and turns and hidden relationships as the Fricks (who, after all, are part of the same family). She's documented all that information at least as thoroughly (and more entertainingly) than many authors who publish books for sale, and she's put it out on the internet for us to have for free. Here's to you, Karen. Besides, if you check out our actual (non-"American Whiskey") home page you'll find we have something in common with you and James. Only in reverse. Who knows? Maybe we all have something in common with Helen and Clay (we learned that he never called himself Henry except on signed documents; his name was Clay in conversation). Oh, and Karen, the presence you felt on the farmhouse stairs in autumn of 1984 wasn't your great, great, great, grandfather, we'll bet. It was Henry Clay Frick. Helen had either just passed or was just about to. Frick had few real friends in life, and even fewer mentors and heroes. He probably wouldn't have placed his grandfather in the first category, but would have put him in the second. And, as we're sure you already know, the truth -- according to Yahoo, AltaVista, Jeeves, Google, et al -- is that, even if West Overton were to be replaced with a shopping mall tomorrow, in the minds of all who care, West Overton is indeed yours. Thank you again for sharing it with us.

Okay, now let's head on down to Connellsville on Jacob's Creek and try to

find Broad Ford. Technically it doesn't exist, at least as a town, but it

still shows up on maps. How to get to the road that leads to it, however,

doesn't show up on maps, at least not very accurately. After driving back

and forth across the river bridge a few times, we finally realize that the

road that says Distillery on the map is actually correct, even though it

stops being Distillery Road almost as soon as you turn on it and then makes

a left turn into a housing development.

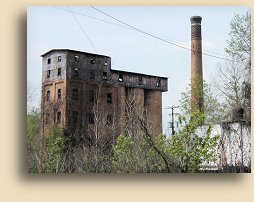

There is a spur road that branches off just

before the turn and disappears under some kind of concrete bridge abutment.

It isn't marked and doesn't even look like a through road, but if taken it

later widens to a single lane and becomes... Distillery Road again. Not that

it actually goes to where the distillery was, of course. That would be asking

too much. But armed with information from a local citizen we asked, we know

to turn off onto the unpaved road near the railroad tracks. Sure enough,

there in front of us is the skeletal remains of one of the most important

distilleries in Pennsylvania whiskey history, the A. Overholt Distilling

Company of Broad Ford.

There is a spur road that branches off just

before the turn and disappears under some kind of concrete bridge abutment.

It isn't marked and doesn't even look like a through road, but if taken it

later widens to a single lane and becomes... Distillery Road again. Not that

it actually goes to where the distillery was, of course. That would be asking

too much. But armed with information from a local citizen we asked, we know

to turn off onto the unpaved road near the railroad tracks. Sure enough,

there in front of us is the skeletal remains of one of the most important

distilleries in Pennsylvania whiskey history, the A. Overholt Distilling

Company of Broad Ford.

Oh, and by the way, in case you're not already

tired of reading this, George Washington slept here, too.

Oh, and by the way, in case you're not already

tired of reading this, George Washington slept here, too.

No, not at the distillery, silly. There wasn't any distillery here then. In fact, except for a German trader named Frazer, there wasn't anyone here of European descent yet. Downstream at Fort Duquesne there were, though. French soldiers enforcing their occupation of land that the Ohio Company of Virginia felt they rightfully owned. That's why George was sent here. The year was 1754 and Washington, a young surveyor working for the land company, was given the assignment to find a route through virgin forests from Virginia to the vicinity of the French fort where Pittsburgh would one day be. The route had to accommodate wagons and swivel guns for the purpose of laying siege to the fort and driving out the French soldiers. On May 20th, he arrived at the "crossing-place" in the Youghiogheny River. The quoted words "crossing-place" indicate a place so named by the warriors of the Delaware tribe. This "crossing-place" became known as Broad Ford. Washington was less successful at routing the French soldiers than he later would be in defeating the British empire; in fact his ultimatum to the French commander brought only arrogant insults and the deaths of fifty-four of his men. However, it was the beginning of what would be known as the French and Indian War, which eventually did push the French out of the western territories. It also taught George Washington some serious tactical lessons that paid off royally twenty-some-odd years later, to our everlasting benefit.

A hundred years after that, in 1854, Abraham Overholt's son Jacob who, with

his brother Henry Stauffer Overholt, was already a partner in the West Overton

distillery, started a new venture with his cousin, Henry O. Overholt (if

you think this is confusing, you ought to try researching this; it seems

like every branch of the family named their children the same.

The only way to tell them apart is by the middle

initials) and built a new distillery at Broad Ford. Here they made and marketed

a brand of whiskey called "Old Monongahela". That might be a little misleading.

Rye whiskey from the western counties had been known as Old Monongahela for

a long time before that. Sam Thompson built his distillery at Brownsville

ten years earlier and that whiskey was called Old Monongahela. In 1851, Herman

Melville published "Moby Dick". Which means he wrote it even earlier than

that. In chapter 84 of the book, the character Stubb wishes, "Would now,

it were old Orleans whiskey, or old Ohio, or unspeakable old Monongahela!"

as types of whiskey (interestingly, he makes no mention of "old Bourbon";

was "bourbon" not yet recognized in New England as a type of whiskey?

). In an essay about the grand time he had at a Fourth of July barbecue --

in Kentucky, of all places -- John James Audubon noted, "Old Monongahela

filled many a barrel for the crowd" (he also doesn't mention bourbon at all).

The essay we found isn't dated, but since Audubon died in 1851 it's pretty

safe to say it would have been before the Overholt distillery was operating

at Broad Ford. And just in case that weren't already enough, there's also

the slight detail that Broad Ford isn't even on the Monongahela river;

it's on the Youghiogheny river.

The only way to tell them apart is by the middle

initials) and built a new distillery at Broad Ford. Here they made and marketed

a brand of whiskey called "Old Monongahela". That might be a little misleading.

Rye whiskey from the western counties had been known as Old Monongahela for

a long time before that. Sam Thompson built his distillery at Brownsville

ten years earlier and that whiskey was called Old Monongahela. In 1851, Herman

Melville published "Moby Dick". Which means he wrote it even earlier than

that. In chapter 84 of the book, the character Stubb wishes, "Would now,

it were old Orleans whiskey, or old Ohio, or unspeakable old Monongahela!"

as types of whiskey (interestingly, he makes no mention of "old Bourbon";

was "bourbon" not yet recognized in New England as a type of whiskey?

). In an essay about the grand time he had at a Fourth of July barbecue --

in Kentucky, of all places -- John James Audubon noted, "Old Monongahela

filled many a barrel for the crowd" (he also doesn't mention bourbon at all).

The essay we found isn't dated, but since Audubon died in 1851 it's pretty

safe to say it would have been before the Overholt distillery was operating

at Broad Ford. And just in case that weren't already enough, there's also

the slight detail that Broad Ford isn't even on the Monongahela river;

it's on the Youghiogheny river.

Anyway, it's not likely that they called it Old Monongahela for long because

one characteristic of that kind of whiskey is that it's aged for several

years. And Jacob died in 1859. He would have been in his mid-forties, in

a family known for long lifespans, and we haven't found any record of how

he died. But at that point his father, Abraham, bought out the 2/3 share

Jacob had owned and, with Henry O. Overholt as a new partner in the business,

continued operations at Broad Ford in addition to the West Overton site.

Whatever the brand was before, it would now be known as "A. Overholt &

Co. Whiskey".

This was also the time when Abraham upgraded

the West Overton distillery and mill into the current building, and they

produced A. Overholt & Co. Whiskey there, too, as well as the Old Farm

brand.

This was also the time when Abraham upgraded

the West Overton distillery and mill into the current building, and they

produced A. Overholt & Co. Whiskey there, too, as well as the Old Farm

brand.

One thing that we find ironic is that the brand we all recognize, "Old Overholt" was never made at West Overton, and in fact was never made by Abraham Overholt at all. After Abraham died in 1870 the Broad Ford distillery and the A. Overholt & Co. business changed hands several times, ending up in the possession of Henry Clay Frick. Somewhere in all that, the brand name was changed to Old Overholt -- possibly for legal reasons, but we'd rather think it was in honor of Abraham -- and that's the way Wanda Hepler told it to us.

The Overholt facility at Broad Ford was a modern distillery. It was rebuilt twice as upgrades with new buildings in 1868 and 1899, and it was rebuilt two other times after major fires in 1884 and 1905. Prohibition closed the West Overton distillery in 1920, but the Broad Ford plant was licensed as a distiller of medicinal spirits and operated during Prohibition. The label eventually ended up in the portfolio of the American Medicinal Spirits Company, and from there to their post-Prohibition incarnation, National Distillers. They had also purchased several other Prohibition-closed distilleries in Pennsylvania and Kentucky and stock from those warehouses was bottled as Old Overholt from the thirties until 1987, when National Distillers was absorbed by Fortune Brands (Jim Beam). We have in our collection bottles of Old Overholt from Broad Ford, which were made before Prohibition, and from after Prohibition we have some which was bottled in Cincinnati, Ohio in the late 1960s or early 1970s. The whiskey is identified only as "Distilled in Pennsylvania". But since there was only one distillery operating in Pennsylvania at that time we're pretty sure that the whiskey is from Shaeferstown, which is not even in western Pennsylvania. And indeed that Old Overholt tastes much more like the Maryland and Kentucky-type rye whiskey.

Another that we have is the bottle mentioned before (made 1934, bottled 1941),

which is actually whiskey from the Large Distillery, which is on the Monongahela

a few miles northwest of Broad Ford. The Large distillery was built by Jonathan

Large (1794-1862), who came to the area from New Jersey at the age of two

with his family in 1797, shortly after the Whiskey Rebillion had ended.

Like Abraham Overholt, Jonathan Large's distillery

produced, on a commercial scale, the Monongahela rye whiskey which his father,

John, had established as a regionally popular product. Management of the

distillery was passed on to Jonathan's youngest son Henry, who is credited

with much of the distillery's success. By 1889, Large Monongahela Rye Whiskey

was a well-known national brand.

Like Abraham Overholt, Jonathan Large's distillery

produced, on a commercial scale, the Monongahela rye whiskey which his father,

John, had established as a regionally popular product. Management of the

distillery was passed on to Jonathan's youngest son Henry, who is credited

with much of the distillery's success. By 1889, Large Monongahela Rye Whiskey

was a well-known national brand.

An amusing side note that we've since learned concerns Jonathan's descendents. Families in those days often produced several children, but Henry Large had only a single daughter, Fannie Laura, who, according to Pittsburgh City Paper writer Chris Potter, staged a whiskey rebellion all her own. Potter quotes Margaret Pearson Bothwell, writing in a 1964 edition of Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, that Fannie "evidently did not share [her father's] pride in the distillery for she was, at one time, President of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union."

Eventually, the Large Distillery was sold to The National Distillery Company, who retired the Large label but bottled the whiskey produced there as Old Overholt. The property was later sold to the Noble Dick Company who leased it in 1958 to Westinghouse, who established a nuclear research facility there, which is now also closed.

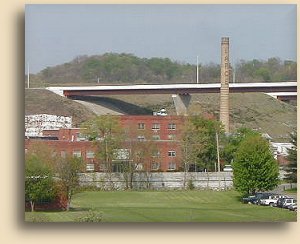

And like West Overton, the employees of the distillery (and later the

Westinghouse facility) lived in the company village of Large. The area along

Route 51 where the distillery once stood is still named

Large. Like the Overholt distillery,

parts of it remain standing even today, such as the ornate brick smokestack.

Unlike Overholt, though, the large distillery's ruins don't rise from a huge

pile of rubble and collapsed brick overgrown with weeds. Located in the sweeping

curve of a major freeway interchange, there are active buildings all

around it, and it looks as if some of the original buildings might be in

use. After circling around a few times we realize that the only way we can

get a good photo will be from a hillside overlooking it, so we head up the

hill and discover... The Old Large Hotel. Of course, in Pennsylvania a "hotel"

doesn't mean a hotel. It means a tavern. Which may or may not have rooms

to rent upstairs, but usually doesn't.

Like the Overholt distillery,

parts of it remain standing even today, such as the ornate brick smokestack.

Unlike Overholt, though, the large distillery's ruins don't rise from a huge

pile of rubble and collapsed brick overgrown with weeds. Located in the sweeping

curve of a major freeway interchange, there are active buildings all

around it, and it looks as if some of the original buildings might be in

use. After circling around a few times we realize that the only way we can

get a good photo will be from a hillside overlooking it, so we head up the

hill and discover... The Old Large Hotel. Of course, in Pennsylvania a "hotel"

doesn't mean a hotel. It means a tavern. Which may or may not have rooms

to rent upstairs, but usually doesn't.

There

really is a town named Large, which consists pretty much of this tavern and

a post office, and many people who have no idea what rye whiskey is have

heard of Large because it's in the Guiness Book of Records and because the

idea of the smallest town in Pennsylvania being named "Large" is cute. The

sign outside the Old Large Hotel is cute, too. Their slogan, illustrated

with a copper pot still, is "Where Good Friends STILL Get Together".

There

really is a town named Large, which consists pretty much of this tavern and

a post office, and many people who have no idea what rye whiskey is have

heard of Large because it's in the Guiness Book of Records and because the

idea of the smallest town in Pennsylvania being named "Large" is cute. The

sign outside the Old Large Hotel is cute, too. Their slogan, illustrated

with a copper pot still, is "Where Good Friends STILL Get Together".

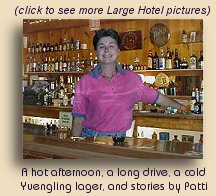

We've been driving all morning.

It's hot. We're dry. An ice cold Iron City beer would be very good right

now. And indeed it is. The tavern is owned by Dale Saller, who has a nice

collection of sealed pre-Prohibition Large Pure Monongahela Rye. Unfortunately,

Dale isn't here to drag out everything he's got in the back (and maybe work

out a trade on something), but our bartender Patti brings out some that are

on display and we can look at them close up. We spend a lot longer enjoying

the beer, the chance to see these old bottles, and Patti's company than we

should. It means we'll later get the extreme pleasure of creeping along highway

51 during afternoon rush-hour traffic, made even more exciting by the fact

that this is also the first day that the tunnel by which most people cross

the river is closed for repairs, and nobody seems to have any idea of where

they're supposed to detour.

We've been driving all morning.

It's hot. We're dry. An ice cold Iron City beer would be very good right

now. And indeed it is. The tavern is owned by Dale Saller, who has a nice

collection of sealed pre-Prohibition Large Pure Monongahela Rye. Unfortunately,

Dale isn't here to drag out everything he's got in the back (and maybe work

out a trade on something), but our bartender Patti brings out some that are

on display and we can look at them close up. We spend a lot longer enjoying

the beer, the chance to see these old bottles, and Patti's company than we

should. It means we'll later get the extreme pleasure of creeping along highway

51 during afternoon rush-hour traffic, made even more exciting by the fact

that this is also the first day that the tunnel by which most people cross

the river is closed for repairs, and nobody seems to have any idea of where

they're supposed to detour.

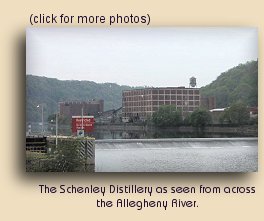

We're creeping along on our way to another town that

doesn't really exist anymore, located on the Allegheny river where it meets

the Kiskiminetas north of Pittsburgh. The town is, or was, Schenley. And

it's the home of... well, the Schenley

Distillery. At least, that's what it was originally called by Frank Sinclaire who started

it on land he acquired from Mary Schenley. That was right at the end of the

century, when Pennsylvania rye's popularity was at an all-time high. The

distillery continued to be very successful until the sledgehammer of Prohibition

put an end to everything.

At least, that's what it was originally called by Frank Sinclaire who started

it on land he acquired from Mary Schenley. That was right at the end of the

century, when Pennsylvania rye's popularity was at an all-time high. The

distillery continued to be very successful until the sledgehammer of Prohibition

put an end to everything.

Well, maybe not quite everything. It did put an end to nearly all of the

hundreds of large distilleries (including the Large distillery, see above),

but it certainly didn't end all the business wheeling and dealing, nor the

investment arrangements that helped to continually rearrange the ownership

of all those thousands of barrels of whiskey.

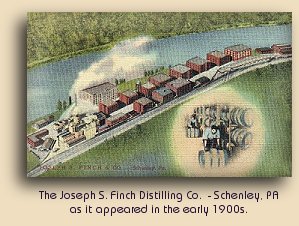

In

1924, New York entrepreneur Lewis S. Rosenstiel began acquiring distilleries.

He started with Sinclaire's Schenley distillery, and also bought another in

the same vicinity, the Joseph S. Finch distillery. Like the Overholts, Joseph

Finch began distilling commercially in the mid-1850s and had a reputation

for excellence. Rosenstiel named his corporation Schenley after the

location, and began modernizing and expanding the Joseph S. Finch Co.

They produced a wide range of Schenley-label beverages, and the new corporation

went on to become the leading U.S. distiller until 1937 and then again from

1944 to 1947.

In

1924, New York entrepreneur Lewis S. Rosenstiel began acquiring distilleries.

He started with Sinclaire's Schenley distillery, and also bought another in

the same vicinity, the Joseph S. Finch distillery. Like the Overholts, Joseph

Finch began distilling commercially in the mid-1850s and had a reputation

for excellence. Rosenstiel named his corporation Schenley after the

location, and began modernizing and expanding the Joseph S. Finch Co.

They produced a wide range of Schenley-label beverages, and the new corporation

went on to become the leading U.S. distiller until 1937 and then again from

1944 to 1947.

Schenley eventually acquired (and closed down) many, many distilleries, including

several small-to-medium sized Kentucky bourbon distilleries. They maintained

one very large one, Buffalo Trace (known then as Ancient Age) which they

operated until 1983. They also owned (and preserved, and rebuilt) Cascade,

one of the only two surviving Tennessee distilleries.

Since they were using the Cascade

brand name on a successful line of Bourbon whiskey, they couldn't use it

on the Tennessee product, so they called that one by the name of its original

distributor, George Dickel.

Since they were using the Cascade

brand name on a successful line of Bourbon whiskey, they couldn't use it

on the Tennessee product, so they called that one by the name of its original

distributor, George Dickel.

In the process of all this capitalism it also ended up with 25 percent

of all the whiskey stored in U.S. warehouses. Schenley has been a name associated

with Canadian whisky for a long time, but it was an enormous presence in

the United States throughout most of the twentieth century.

They

even owned Old Overholt for awhile, according to the Mennonite Historical

Society of Canada. In Canada, Schenley was right up there with Seagram and

Hiram Walker. There is a lot we'd like to learn about Schenley, but that

will have to wait until we're ready to bring in the whole world of Canadian

whisky and the Prohibition years, and the connections between the American

distiller barons and the Canadian ones. We need to change our theme then

to "North American Whiskey". We'll also need to buy a bigger house.

They

even owned Old Overholt for awhile, according to the Mennonite Historical

Society of Canada. In Canada, Schenley was right up there with Seagram and

Hiram Walker. There is a lot we'd like to learn about Schenley, but that

will have to wait until we're ready to bring in the whole world of Canadian

whisky and the Prohibition years, and the connections between the American

distiller barons and the Canadian ones. We need to change our theme then

to "North American Whiskey". We'll also need to buy a bigger house.

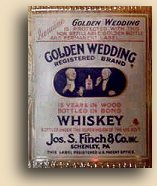

One interesting thing we learned. All the Canadian Schenley brands, including the ones that used to be American bourbon and rye brands, like OFC (once George T. Stagg's brand), Golden Wedding (Finch and maybe Guckenheimer), Gibson's, and others, are now distributed (and probably made) by Barton in Bardstown Kentucky.

So, in the meantime, we have managed to crawl through the traffic until we've

outrun it, and are arriving at... uh... nothing. There is no Schenley anymore.

Well, there is, but it pretty much consists of a train station and some steel

rail track. It's owned by the Kiski

Junction Railroad, a railroad enthusiast's dream with one of the best

websites we've seen. If you're planning to visit the ruins of the Schenley

distillery, you'd better not even try getting there by way of a Pennsylvania

road map. Go to

http://www.kiskijunction.com/roadsigns.html

and check out the outstanding (and entertaining) directions written by " The

Mary Brakeman from the KJR: Mother of 4, Grandmother of 9, (veteran of many

road trips) & Wife to Charlie "I know where we are"..(yea sure- pull

over)! hahahah.:)."

The

Mary Brakeman from the KJR: Mother of 4, Grandmother of 9, (veteran of many

road trips) & Wife to Charlie "I know where we are"..(yea sure- pull

over)! hahahah.:)."

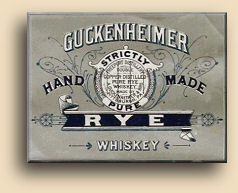

And then there's Freeport. Where we'll spend hours driving around a town

the size of two football fields looking for the remains of the Pennsylvania

Distilling Company, one-time makers of Guckenheimer Rye. They might also

have been part of the Schenley group, since they made a whiskey called

Golden Wedding, which Schenley also made and which is now part of the Canadian

portfolio.

By

the early 1900s, Guckenheimer was one of the largest rye whiskey facilities

in the world, using 2,100 bushels of grain every day. And today? No

one in Freeport even knows where it once was. We finally find an elderly

gentleman who remembers there being a distillery. He directs us up, down,

around, through, and under, after which we arrive at... the Schenley

distillery????

By

the early 1900s, Guckenheimer was one of the largest rye whiskey facilities

in the world, using 2,100 bushels of grain every day. And today? No

one in Freeport even knows where it once was. We finally find an elderly

gentleman who remembers there being a distillery. He directs us up, down,

around, through, and under, after which we arrive at... the Schenley

distillery????

That's all, folks. Where's

the motel?

January 2007:

Thanks to our readers, we have found the

A. Guckenheimer & Bros. Distillery

Click here to visit it NOW!!

![]()