Messin' 'Round The Old Mawn-Nonga-Heelah

Oh, 'tis "Whiskey!, Rye Whiskey!, Rye Whiskey!!" I cry

![]()

Of

course, the example benefits enormously from Abraham's great, great, great

granddaughter Karen Critchfield's exhaustive (and continuing)

research into

that branch of her family.

Of

course, the example benefits enormously from Abraham's great, great, great

granddaughter Karen Critchfield's exhaustive (and continuing)

research into

that branch of her family.

But, like we said, there were others. Many others. Our expedition through the world of Old Monongahela now brings us to the point in time where American Rye Whiskey has become a world-class business. It is beginning to influence other whiskey makers' notions of what American whiskey should taste like. Rye whiskey produced in the east, where it doesn't take months to be marketed, is beginning to be aged in oak barrels anyway. And for years, not months. Because the demand is now for that flavor and that red-brown color. Thanks to, first the steamboat, then the railroad, transportation even from the western counties can now be measured in days instead of months. But the customers want two- to four-year-old, barrel aged whiskey, so the distillers are now aging their rye in warehouses intentionally. And that means, under measurements and controls. And that means better whiskey. By the 1840s people all over the world know what Old Monongahela is. It's different from "ordinary whiskey". It's reddish brown and has flavors in it that the local kind doesn't have. Flavors such as vanilla and tannin and leather and tobacco, all of which comes from the barrel the whiskey is aged in. The same situation is happening down-river in Kentucky. By the 1850s, Kentucky distillers are beginning to apply the same techniques to their particular style of maize, rye, and barley whiskey. And, like "Old Monongahela" became a descriptor claimed by distillers making that kind of whiskey, no matter where they were located, Old Bourbon would come to have a similar meaning in Kentucky.

The 19th century really belonged to Monongahela, though. The product grew up all through the century, completely dominating the whiskey industry. Kentucky bourbon, which started its marketing growth about a decade later than in Pennsylvania, would probably have overtaken it except that the Kentucky distillers were devastated by the Civil War's annihilation of nearly all the transportation. Railroads were destroyed. River shipping was stopped. Even overland roads were wrecked. All as part of the war. None of that happened in Pittsburgh, or Philadelphia, or Baltimore. So the Monongahela Monarchy remained throughout that period. And while distillers in Kentucky and Tennessee were trying to recover, the distillers in the north were growing huge.

Of course, the Kentucky and Tennessee distillers did catch up. And then came the real whammy... On the twentieth day of January, 1920, everything came to a screeching halt. The 18th Amendment brought National Prohibition and prohibition brought the Volstead Act. It was illegal to manufacture, transport, sell, and, at least in a defacto sense, even possess any product containing more than one half of one percent alcohol. To get a better idea of what effect this had, consider this... we look back, either in memory or in history, on a fourteen year period of terrible dysfunction. Looking forward in 1920 (and '21, '22, '23, etc) there was no reason to suspect it would end at all. The proudly declared goal of the temperance movement, which, as far as anyone knew, had been accomplished, was the banning of all alcohol in the United States FOREVER.

And when it all was over, the Kentucky bourbon distillers began climbing out of the wreckage and began to heal. The distillers in Tennessee had been crushed even before Prohibition went national, and with the exception of two companies that been purchased by Kentucky distillers, not a single one ever came back. Pennsylvanians and Marylanders emerged from the debris, and some held on and grew. But only a few, and the combination of WWII and the anti-alcohol generation of the sixties did even those in.

So the twentieth century is Bourbon's. But the nineteenth is Monongahela's,

and there are more relics to uncover.

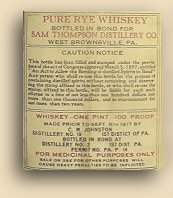

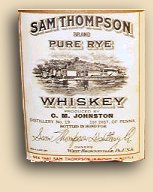

Sam Thompson Pure Rye

We visit in 2003

We've already visited the remains of the distillery Jonathan

Large and his son Henry ran near

West Mifflin, and now we're headed up the river a few miles to the Sam Thompson Distillery,

in West Brownsville.

Or is it in Brownsville?

Or is it in South Brownsville?

Or is there even a South Brownsville?

Oh, I see... I think.

Or maybe not.

It seems that Sam Thompson's distillery was in West Brownsville, on the west

side of the Monongahela river. Except that when we get to that side of the

river there doesn't appear to be a trace of the buildings we've seen in photos.

So we check out the other side of the river, ignoring "No Outlet" signs and

trying NOT to ignore stoplights, while also trying to stay close enough to

see across the river.

Sure enough, we do see an old

building that looks like a whiskey warehouse.

Sure enough, we do see an old

building that looks like a whiskey warehouse.

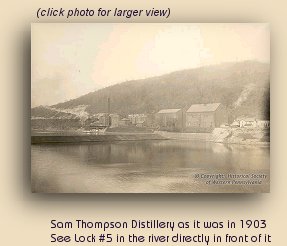

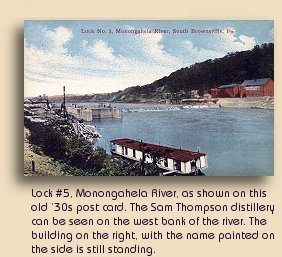

And we can just barely make out where the words "SAM THOMPSON DISTILLERY" may have once, long ago, been painted on the side facing the river. But all the photographs we've seen show the distillery next to "the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Lock No. 5" on the river. Well, there is no lock here. So this can't be the place. That must be a warehouse separate from the distillery site, like many of the Kentucky distilleries we're familiar with. Back and forth we go again, and again we find a local resident and ask about Lock #5. This guy's younger than the fellow we met in Freeport.

"Oh, sure," he says to us. "Yun's're on the wrong side of town. Ya gotta go uptuda light and then go owdda town that way. You'll see it". When John was a rotten teenager, he lived in a seaside tourist area. And like most of the other rotten teenagers he hung out with, when people would come by in their out-of-state cars and ask for directions... well, you get the idea.

The area where we keep coming back to is the one from which we can see that old warehouse across the river. Brownsville, Pennsylvania is actually made up of three communities tied together by bridges.

West Brownsville, across the river, is one.

Downtown Brownsville, with its eerie sections of block after block of old abandoned pre-Civil War buildings and storefronts, is another.

And this area, known as Bridgeport, is the third. About fifteen or sixteen

blocks long and three blocks wide, the area is made up of small houses and

little commercial buildings, all arranged around Water Street. But the houses

aren't jammed together the way they often are in small Pennsylvania towns.

There are no mansions here,

but we don't see any row homes, either. We also don't see Lock #5. But do

see the ruins of a brewery. And a coal yard.

There are no mansions here,

but we don't see any row homes, either. We also don't see Lock #5. But do

see the ruins of a brewery. And a coal yard.

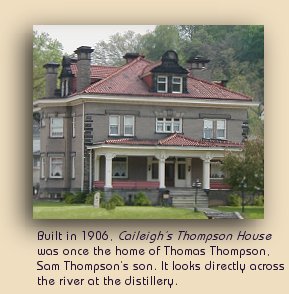

And did we say there weren't any mansions? WRONG!!

There is indeed a mansion, and it's directly across the river from that Sam Thompson warehouse, and it's been converted into a fine restaurant and shops. And on the front the sign says, "Caileigh's Restaurant" and looks inviting. Especially since a larger sign reads, "The Thompson House". We think it's a great time to stop for lunch and to figure out whether those buildings over there are or aren't the Sam Thompson distillery, and how can we miss seeing something as obvious as a dam across the river.

The Thompson House -- which is also called the Wayside Manor -- was built

in 1906 by Thomas H. Thompson, distiller Sam Thompson's son. A Classic Revival

building with a Spanish-style tiled roof built of limestone and brick, it

was known as the most extravagant house in Brownsville, with 11 bathrooms,

a third-floor ballroom, hardwood floors with different inlays in each room

on the first floor, a pair of magnificent 6-foot wide oak staircases, and

something like seven fireplaces, each with its own unique tile facing. The

entire building isn't Caileigh's; there's a bar and the rooms upstairs have

been converted to

The Thompson House -- which is also called the Wayside Manor -- was built

in 1906 by Thomas H. Thompson, distiller Sam Thompson's son. A Classic Revival

building with a Spanish-style tiled roof built of limestone and brick, it

was known as the most extravagant house in Brownsville, with 11 bathrooms,

a third-floor ballroom, hardwood floors with different inlays in each room

on the first floor, a pair of magnificent 6-foot wide oak staircases, and

something like seven fireplaces, each with its own unique tile facing. The

entire building isn't Caileigh's; there's a bar and the rooms upstairs have

been converted to

boutique shops so that, in effect, the mansion is

a little mini-mall. Caileigh's is just the restaurant in the mini-mall. It

occupies the first floor, and we occupy a table by the window. There's nothing

stuffy or oldish about the restaurant; sunlight pours through the large windows,

softened by lace curtains. The atmosphere is similarly cheery. The lunch

menu includes a Monte Cristo sandwich, which pretty much takes care of John's

selection choices. A significant clause in John's personal restaurant code

is that, if a restaurant offers Monte Cristo sandwiches, it needn't bother

wasting ink listing other items on the menu. Of course, John has similar

clauses concerning Kentucky hot brown and soft-shell crabs, too. Fortunately,

we have yet to discover a restaurant that serves more than one of those.

We'd probably have to leave, as the only logical solution, combining two

or more, sounds truly disgusting. John says that if such a situation should

occur, it would probably be the only time he'd feel justified in ordering

a chicken salad sandwich instead. Linda does order a chicken salad, although

it isn't a sandwich and the grilled chicken is succulent and juicy and she

enjoys it almost as much as John does his.

boutique shops so that, in effect, the mansion is

a little mini-mall. Caileigh's is just the restaurant in the mini-mall. It

occupies the first floor, and we occupy a table by the window. There's nothing

stuffy or oldish about the restaurant; sunlight pours through the large windows,

softened by lace curtains. The atmosphere is similarly cheery. The lunch

menu includes a Monte Cristo sandwich, which pretty much takes care of John's

selection choices. A significant clause in John's personal restaurant code

is that, if a restaurant offers Monte Cristo sandwiches, it needn't bother

wasting ink listing other items on the menu. Of course, John has similar

clauses concerning Kentucky hot brown and soft-shell crabs, too. Fortunately,

we have yet to discover a restaurant that serves more than one of those.

We'd probably have to leave, as the only logical solution, combining two

or more, sounds truly disgusting. John says that if such a situation should

occur, it would probably be the only time he'd feel justified in ordering

a chicken salad sandwich instead. Linda does order a chicken salad, although

it isn't a sandwich and the grilled chicken is succulent and juicy and she

enjoys it almost as much as John does his.

Our waitress is a lovely young lady who would probably not be considered

old enough to carry the wine out to our table if we were dining in Ohio.

She knows nothing at all about the Sam Thompson distillery. Or about Lock

#5. Which, it later turns out, shouldn't be too surprising, since her

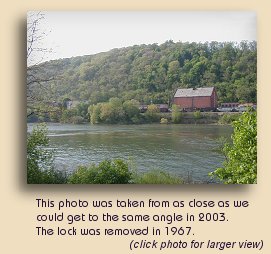

parents were probably toddlers when it was demolished by the Army Corps of

Engineers in the summer of 1967. And where was it? Well, look out the window

-- see that little playground park right in front you? Imagine a line between

that and the Thompson Distillery

warehouse.

According to his grandson, Samuel J. Thompson, Sam (the elder) hadn't started out with the idea of distilling whiskey at all. In 1844 he acquired the first distillery at this site from a man who owed him money. He would have preferred being paid back, but the distillery was his only option. The story goes on that Sam, the new whiskeymaker told a friend that he had a distillery on his hands, and did not know what to do with it. There were many distilleries along the river in those days, and competition was so keen that there was not much money in the business for any of them. The friend old Thompson to make better whiskey than the others. He did make better whiskey, beginning in that year of 1844, and West Brownsville became known as the "Home of Sam Thompson's Old Monongahela Rye."

In the pictures can be seen two large warehouses next to one another, and

third large building that was Ward Supply Company, even back then. There

are also other, smaller buildings. The Ward Supply Company still stands,

as does the warehouse on the right. That was Sam Thompson Distillery Bonded

Warehouse No. 4. The warehouse that was between them is gone, replaced by

another commercial building about half as high. It looks like it was

built in the late 1950s or early '60s. That building, too, is closed. There

is another building which is used as the business office for the Ward Supply

Company, but was the office of the government gauger and barreling line when

the distillery was in operation. Before that it was the Owens Tavern, and

pre-dated any of the other buildings.

It may have been built as early as

1794, which is when it's original owners, the Krepps family, began

operating a ferry service at that location. They later opened another,

also with a tavern, about eight miles up the river, which is better known.

It may have been built as early as

1794, which is when it's original owners, the Krepps family, began

operating a ferry service at that location. They later opened another,

also with a tavern, about eight miles up the river, which is better known.

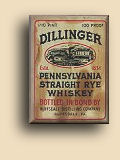

Sam Thompson Monongahela Rye Whiskey emerged from

Prohibition and continued to be made and bottled deep into the second half

of the twentieth century. But not from West Brownsville. Purchased by

Schenley, the label adorned bottles of Allegheny rye made in Aladdin, and

even East Pennsylvania rye from PennCo (Michter's).

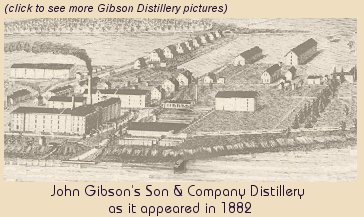

John Gibson's Son & Company

(also

known as Moore & Sinnott)

About halfway between West Brownsville and West Mifflin, we

find Belle Vernon, and what's left of the Gibson Distillery, which was

also known as Moore & Sinnott.

In 1856 John Gibson purchased over forty acres to build a distillery on the

east bank of the Monongahela River, across from where Charleroi is today

and just north of the Belle Vernon Bridge. In addition to using rye,

he also made whiskey from wheat and malt. Interestingly, we've found no reference

to corn (maize) being used at the Gibson distillery.

The

site contained the distillery, eight bonded warehouses, a four-story malt

house, a drying kiln, a grist mill, a saw mill, two carpenter shops, a blacksmith

shop, an ice house, and a cooper shop.

The

site contained the distillery, eight bonded warehouses, a four-story malt

house, a drying kiln, a grist mill, a saw mill, two carpenter shops, a blacksmith

shop, an ice house, and a cooper shop.

The cooper shop was where the barrels to hold the whiskey were made. The

records indicate that the barrels were made of oak and the wood was aged

three years before the barrel was assembled. The fact that they made their

own cooperage means there's a good chance that they were using new barrels

for at least some of their whiskey. We have not, however, found anything

to indicate that charring the inside of the

barrel was part of their process,

although we suspect it may have been. Filled barrels went either into bonded

warehouses, or directly to their wholesale customers. Those customers apparently

included at least one commercial spirits bottler who purchased Moore &

Sinnott whiskey for use in making French brandy (a spirit associated with

a distinctive oak flavor and reddish-brown hue that is distilled from

grape wine, not grain mash, and is not ordinarily considered to be related

to whiskey as it was most commonly known before the 1850s).

barrel was part of their process,

although we suspect it may have been. Filled barrels went either into bonded

warehouses, or directly to their wholesale customers. Those customers apparently

included at least one commercial spirits bottler who purchased Moore &

Sinnott whiskey for use in making French brandy (a spirit associated with

a distinctive oak flavor and reddish-brown hue that is distilled from

grape wine, not grain mash, and is not ordinarily considered to be related

to whiskey as it was most commonly known before the 1850s).

When John Gibson died, his son Henry C. Gibson formed a new company with

Andrew M. Moore and Joseph F. Sinnott.

The distillery was

renamed "John Gibson's Son & Company", and production continued to grow.

The distillery was known as "Moore & Sinnott" after Henry retired (although

the name would eventually change back to Gibson Distilling Company).

During this time, in the early 1880s, Moore & Sinnott was the world's

largest manufacturer of rye whiskey, a position it would maintain throughout

the next three decades until Prohibition. The distillery was producing 150

barrels of whiskey a day. At about $80 per barrel, that would represent $12,000

($223,030 in 2003 dollars) daily. At its peak, they were shipping 5,000

railroad carloads of barrels a year.

The distillery was

renamed "John Gibson's Son & Company", and production continued to grow.

The distillery was known as "Moore & Sinnott" after Henry retired (although

the name would eventually change back to Gibson Distilling Company).

During this time, in the early 1880s, Moore & Sinnott was the world's

largest manufacturer of rye whiskey, a position it would maintain throughout

the next three decades until Prohibition. The distillery was producing 150

barrels of whiskey a day. At about $80 per barrel, that would represent $12,000

($223,030 in 2003 dollars) daily. At its peak, they were shipping 5,000

railroad carloads of barrels a year.

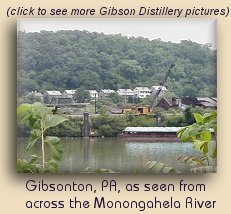

Like West Overton, a thriving company community soon grew around the distillery. Known as Gibsonton, it was recognized with a U.S. post office in July of 1884. By 1893 there were over 150 houses in Gibsonton.

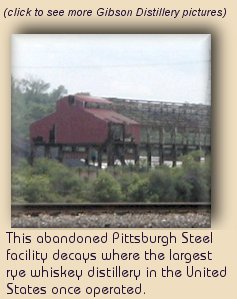

In 1920, the 18th Amendment brought the disgrace of national prohibition,

and the Gibson Distilling Company went bankrupt. On Tuesday, September 8,

1923, a sheriff's sale was held and when it was over nothing remained of

the distillery except the buildings.

The Pittsburgh Steel

Company acquired the property. In 1926, the limestone buildings were dismantled

and the blocks sold at $1.00 a load.

The Pittsburgh Steel

Company acquired the property. In 1926, the limestone buildings were dismantled

and the blocks sold at $1.00 a load.

A

steel-fabricating plant was constructed on the site, and even that's now

long gone, the skeletons of its own huge buildings, abandoned for

decades, now collapsing in on themselves.

A

steel-fabricating plant was constructed on the site, and even that's now

long gone, the skeletons of its own huge buildings, abandoned for

decades, now collapsing in on themselves.

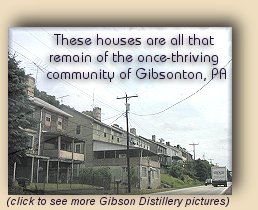

The town of Gibsonton, like West Overton, no longer exists; at least there

isn't a post office there anymore. But unlike the Overholt's workers'

community, it isn't entirely a ghost town. There are about a dozen duplex

houses remaining along a road that is called either "Gibsonton" or just "Gibson",

depending on which sign you believe, and people live there. As an area of

Belle Vernon, Gibsonton shows up on some maps, but not others. And although

many people no longer remember Gibsonton, others do. Driving east on I-70

toward Belle Vernon, we turn off just before the bridge across the Monongahela

River and drive north along the west river bank a couple miles toward Charleroi.

The other side of the river is lined with industrial sites. Some are active

and others are only decaying remnants. We're pretty sure that the old Gibson

Distillery was located in this approximate area, and we pull into a convenience

store to ask if anyone knows where it might be.

The proprietor, a man

about John's age with a scraggly beard, has heard of Gibsonton, but isn't

sure where it is. He calls a friend, and the his friend knows exactly. There

is, of course, no trace of the distillery, but the row of houses that remain

of Gibsonton are directly across the river from us. He even tells us how

to get there. We buy a bottle of pop and thank him; then John crosses the

highway and railroad tracks to take these pictures of Gibsonton and the ruins

of the steel plant that replaced the distillery eighty years ago. Later,

as we drive through the area to get a closer look, we notice a steel bridge

which leads from the housing area toward the plant site. We think it might

have been from the Pittsburgh Steel Company, but it looks picturesque and

we photograph it anyway. If anyone knows whether this bridge led to the

distillery or the steel plant, please let us know.

The proprietor, a man

about John's age with a scraggly beard, has heard of Gibsonton, but isn't

sure where it is. He calls a friend, and the his friend knows exactly. There

is, of course, no trace of the distillery, but the row of houses that remain

of Gibsonton are directly across the river from us. He even tells us how

to get there. We buy a bottle of pop and thank him; then John crosses the

highway and railroad tracks to take these pictures of Gibsonton and the ruins

of the steel plant that replaced the distillery eighty years ago. Later,

as we drive through the area to get a closer look, we notice a steel bridge

which leads from the housing area toward the plant site. We think it might

have been from the Pittsburgh Steel Company, but it looks picturesque and

we photograph it anyway. If anyone knows whether this bridge led to the

distillery or the steel plant, please let us know.

There may be nothing left of Moore and Sinnott, the largest rye distillery ever, but the ruins of the second largest still dominate the tiny town where it continued to make fine rye whiskey as late as the mid 1960s. In fact, some of their rye whiskey may even have made its way into the Schenley-produced bottles of Sam Thompson. The distillery is also named "Sam", and so is the fascinating man who introduced it to us.

Sam Dillinger

(also

known as the Ruffsdale Distillery)

We visit in September 2004

I guess if Tommy Sienkevich hadn't hit the ball so hard,

back when men were walking on the moon, Frank Sinatra was doing it his

way,

Tammy Wynette was standing by her man, and the Beatles were getting

back to where they once belonged, we'd

probably never have seen the one of Pennsylvania's most successful

old whiskey distilleries. The huge abandoned buildings stood all the way

across the railroad tracks, rising out of a sea of weeds and rusted

equipment, behind a chain link fence. And that's where young Sam Komlenic had to

go to recover their baseball. The plant and warehouses, with billboards

of forbidden secrets like Thos. Moore "Old Possum Hollow" and "Old Yock"

Straight Rye Whiskey painted on the walls, had been abandoned as far back

as Sam could remember. And it remained that way as he grew to adulthood

and moved away from the quiet little town of Ruff's Dale (or Ruffsdale,

depending on who you ask). But he never forgot about the vacant

distillery.

Tammy Wynette was standing by her man, and the Beatles were getting

back to where they once belonged, we'd

probably never have seen the one of Pennsylvania's most successful

old whiskey distilleries. The huge abandoned buildings stood all the way

across the railroad tracks, rising out of a sea of weeds and rusted

equipment, behind a chain link fence. And that's where young Sam Komlenic had to

go to recover their baseball. The plant and warehouses, with billboards

of forbidden secrets like Thos. Moore "Old Possum Hollow" and "Old Yock"

Straight Rye Whiskey painted on the walls, had been abandoned as far back

as Sam could remember. And it remained that way as he grew to adulthood

and moved away from the quiet little town of Ruff's Dale (or Ruffsdale,

depending on who you ask). But he never forgot about the vacant

distillery.

How could he, when it served as the backdrop to so many of the

things high school kids did then (and hopefully still do)?

How could he, when it served as the backdrop to so many of the

things high school kids did then (and hopefully still do)?

Then, around 2001 or '02, Sam Komlenic, now forty-something and

fascinated by the romance of Pennsylvania's once-important rye whiskey

history, was searching the internet for information on that long-abandoned

Sam Dillinger Distillery in Ruffsdale. The couple of sentences we'd

written mentioning Sam Dillinger popped up, and Komlenic emailed us asking

if we'd be interested in more about it.

And Sam sure did have more about it. Lot's more. Sam has photos and

postcards from the century before last, letters and correspondence between

the distillery and other companies, promotional items like matchbooks and

swizzle sticks, and scrapbooks of old advertisements. He has a mountain of

knowledge, and a chasm of curiosity. And over the course of many emails

he has shared much of his learnings with us. As his investigations

continue, he often tells us what he's learned lately.

So when we found we would be going back to the Monongahela valley again,

we asked Sam if he'd be interested in joining with us there. Sam lives

about half as far from Westmoreland county as we do, in the other

direction, and he hadn't been back to Ruff's Dale in over two decades, but

he immediately and enthusiastically agreed and we joined up for breakfast

on a crisp Saturday morning in 2003 at our old friend, the Cracker Barrel Restaurant in

New Stanton.

The first place we visit, sort of, is the one-time site of a distillery that once operated in Greensburg, just a few minutes up the road from New Stanton.

Until the arrival of Prohibition, Greensburg Distilling made rye whiskey at a building along South Main Street. The first time we passed through this area it was too dark and rainy and late to see anything. This time we're able to visit it in the daytime, but unfortunately there isn't anything to visit. If it hadn't been for Sam Komlenic's research we'd have never guessed a distillery had ever existed here. The site, a much newer set of buildings at the foot of Green Street, now contains the offices of the Westmoreland County Blind Association, with an industrial fuel & solvent company in the back. What had probably been the mill creek now flows across the property in a concrete trough, and there is an old, three-story brick building way in the back that might once have been a whiskey warehouse, but there's no way to tell. Otherwise, there is no longer any trace of this distillery.

The

Sam Dillinger

distillery, which was also known as the

Ruffsdale Distillery,

is quite another story.

There

is still plenty to see here. There's also plenty of reason to, because

this was a very important distillery in its day. And it's "day" was a long

one, starting in the mid-1800s and extending all the way into the 1960s.

There

is still plenty to see here. There's also plenty of reason to, because

this was a very important distillery in its day. And it's "day" was a long

one, starting in the mid-1800s and extending all the way into the 1960s.

Samuel

Dillinger, who was born in Westmoreland county October 28, 1810, was the eldest child of Daniel and Mary (Myers) Dillinger.

His father had emigrated from eastern Pennsylvania, very possibly from the

same Bucks county area as the Overholts, and we have some

evidence that the family may have shared with the Boehms and Overholts their

Swiss-Palatine-Mennonite origins . The name, Dillinger, by the way is

pronounced "Dilling-Grrr", not "Dillon-Jerr"

His father had emigrated from eastern Pennsylvania, very possibly from the

same Bucks county area as the Overholts, and we have some

evidence that the family may have shared with the Boehms and Overholts their

Swiss-Palatine-Mennonite origins . The name, Dillinger, by the way is

pronounced "Dilling-Grrr", not "Dillon-Jerr"

As a young man he worked at Martin

Stauffer's mill and distillery, near Jacob's Creek. He may have learned to

distill rye whiskey there, but more importantly, he learned about the

business of distilling... and of marketing farm products. Around 1831 he and

his new bride, Sarah, bought their own farm near Alverton.

And

again it appears, from his biography in John N. Boucher’s 1906

"History

of Westmoreland County ",

that his focus was on the business of farming, of buying and selling cattle

and horses, of marketing and transportation. For several years he drove a

large Conestoga wagon with a team of six horses across the Allegheny

mountains on the National Pike, transporting merchandise between the cities

of Pittsburgh and Baltimore.

And

again it appears, from his biography in John N. Boucher’s 1906

"History

of Westmoreland County ",

that his focus was on the business of farming, of buying and selling cattle

and horses, of marketing and transportation. For several years he drove a

large Conestoga wagon with a team of six horses across the Allegheny

mountains on the National Pike, transporting merchandise between the cities

of Pittsburgh and Baltimore.

About 1850 he purchased a custom grist

mill in nearby West Bethany, and soon added a distillery, both of which he

operated successfully for about thirty years. In 1881 they were entirely

destroyed by fire, and a new distillery was built just on the other side of

the ridge, at Ruff’s Dale.

His two sons, Daniel L. and Samuel L., joined him

in this endeavor and the distillery, operated as S. Dillinger and Sons,

became one of the largest and best known in the state of Pennsylvania. By

1906 it was producing fifty barrels a day, with 55,000 barrels in storage,

and was second in size only to the Gibson Distillery near Belle Vernon.

His two sons, Daniel L. and Samuel L., joined him

in this endeavor and the distillery, operated as S. Dillinger and Sons,

became one of the largest and best known in the state of Pennsylvania. By

1906 it was producing fifty barrels a day, with 55,000 barrels in storage,

and was second in size only to the Gibson Distillery near Belle Vernon.

In

addition to the distillery in Ruff's Dale they operated or supplied several

bottlers and rectifying companies.

In

addition to the distillery in Ruff's Dale they operated or supplied several

bottlers and rectifying companies.

And liquor dealers. Among their customers was the Rosenbloom family, who operated a well-established liquor dealership in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, now part of Pittsburgh's North Side. Among their house bottlings was Rosenbloom’s Oak Leaf Pure Rye Whiskey, which may have been produced by Dillinger.

They would play an important role in the reincarnation of the distillery.

In 1889 a sudden illness ended Sam

Dillinger's life. And in 1919 the Volstead Act ended the alcohol beverage

industry in America. It was not generally considered to be a temporary

hiatus; An amendment to the United States Constitution had never been

reversed, and the expectation of the 18th was that there would not again be

alcoholic beverages in America. Ever. Of the hundreds of distilleries with

their own brands that had existed up to then, nearly all ended up simply

abandoning their now-worthless distilleries and other assets.

And in 1919 the Volstead Act ended the alcohol beverage

industry in America. It was not generally considered to be a temporary

hiatus; An amendment to the United States Constitution had never been

reversed, and the expectation of the 18th was that there would not again be

alcoholic beverages in America. Ever. Of the hundreds of distilleries with

their own brands that had existed up to then, nearly all ended up simply

abandoning their now-worthless distilleries and other assets.

There were,

however, a few visionaries who had faith in either the temporary nature of

"The Great Experiment" or in the investment potential of the bootlegging

industry it would inevitably spawn and nurture. And these individuals were

quite willing to purchase the existing stock, the names, and labels

of the others. Sam Bronfman (Seagram's) was one; Lew Rosenstiel

(Schenley), Buddy Thompson (Glenmore), the Fleischmann company, and the

American Medicinal Spirits Company (later to become National Distillers)

were others. In addition to these national giants, though, were smaller,

more regional investors, such as the liquor dealer in Allegheny. And thus,

when Prohibition was repealed in 1934, the Dillinger Distilling Company had

already been renamed the Ruffsdale (one word) Distilling Company, and was

owned by the Rosenbloom family.

There were,

however, a few visionaries who had faith in either the temporary nature of

"The Great Experiment" or in the investment potential of the bootlegging

industry it would inevitably spawn and nurture. And these individuals were

quite willing to purchase the existing stock, the names, and labels

of the others. Sam Bronfman (Seagram's) was one; Lew Rosenstiel

(Schenley), Buddy Thompson (Glenmore), the Fleischmann company, and the

American Medicinal Spirits Company (later to become National Distillers)

were others. In addition to these national giants, though, were smaller,

more regional investors, such as the liquor dealer in Allegheny. And thus,

when Prohibition was repealed in 1934, the Dillinger Distilling Company had

already been renamed the Ruffsdale (one word) Distilling Company, and was

owned by the Rosenbloom family.

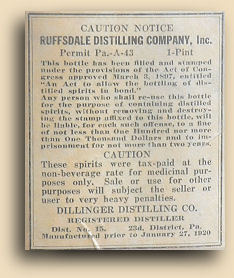

It

would later revert to Dillinger Distilling Co. probably around 1940 when it

was sold again. Dillinger was registered distillery No. 15 in the 23rd

district of PA.

It

would later revert to Dillinger Distilling Co. probably around 1940 when it

was sold again. Dillinger was registered distillery No. 15 in the 23rd

district of PA.

In his 1937 edition

of "The Liquor Industry: A Survey of its History, Manufacture, Problems

of Control and Importance", published by Ruffsdale Distilling Co., Morris

Victor Rosenbloom thanks numerous influences on his project, including “my

father, Alfred A. Rosenbloom, Treasurer of the Ruffsdale Distilling Company,

and my uncle, Israel Rosenbloom, President.” Young Morris,

however, didn't follow his father and uncle into the beverage alcohol

business.

Earning

a listing in "Who's Who in America", Morris V. Rosenbloom became more widely

known as a holder of several government positions and Bernard Baruch's

biographer. He also authored a companion volume,

"Bottling for Profit: A Treatise on Liquor and Related Industries"

as a post-graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh. They are

considered textbooks for the trade.

Earning

a listing in "Who's Who in America", Morris V. Rosenbloom became more widely

known as a holder of several government positions and Bernard Baruch's

biographer. He also authored a companion volume,

"Bottling for Profit: A Treatise on Liquor and Related Industries"

as a post-graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh. They are

considered textbooks for the trade.

Sam Komlenic has a letter from sometime just after repeal

which is signed by Allan M. Rosenbloom, Vice-President. Sam also

speculates that the company may have become Dillinger Distilleries,

Inc. when ownership was obtained by interests in Meadville, Pennsylvania.

It is known that they were operating as such by 1941. Ruffsdale Distilling

had offices and a blending plant in Braddock and later, offices in

Pittsburgh.

The

blending plant, also referred to as the “rectifying plant”, was located at

708-14 Pine Way, Braddock.

The

blending plant, also referred to as the “rectifying plant”, was located at

708-14 Pine Way, Braddock.

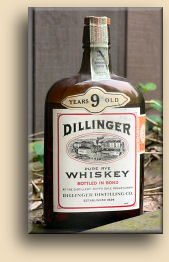

Another well-known brand that became part of the Ruffsdale

portfolio was Thos. Moore, produced before Prohibition in McKeesport, a town

at the confluence of the Youghiogheny and Monongahela rivers.

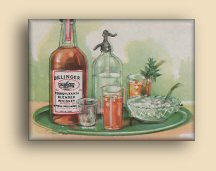

In fact, it

was Thos. Moore Old Possum Hollow, not Sam Dillinger, that was their flagship

brand. Thos. Moore, (“It’s old enough to speak for itself

”; $2.25 per quart, $1.15 per pint) was 100-proof, bottled-in-bond

straight rye whiskey. Their other rye was Old Man (90 proof; “A

Revelation in Mellowness ”; $1.34 per quart, $.70 per pint), which was

neither. Their blended whiskies (both at 90 proof) were Dillinger ($2.09 per

quart, $1.05 per pint), Hiram Green (“A favorite before prohibition and

since the first days of repeal "; $1.59 per quart, $.85 per pint),

and Tom Keene (90 proof; $1.34 per quart, $.70 per pint).

In fact, it

was Thos. Moore Old Possum Hollow, not Sam Dillinger, that was their flagship

brand. Thos. Moore, (“It’s old enough to speak for itself

”; $2.25 per quart, $1.15 per pint) was 100-proof, bottled-in-bond

straight rye whiskey. Their other rye was Old Man (90 proof; “A

Revelation in Mellowness ”; $1.34 per quart, $.70 per pint), which was

neither. Their blended whiskies (both at 90 proof) were Dillinger ($2.09 per

quart, $1.05 per pint), Hiram Green (“A favorite before prohibition and

since the first days of repeal "; $1.59 per quart, $.85 per pint),

and Tom Keene (90 proof; $1.34 per quart, $.70 per pint).

Blended whiskey at

that time apparently didn't carry the stigma that it later acquired; notice

that bottom-shelf Tom Keene was the only whiskey not more expensive than the

second-level pure rye. The product line also included Old Yock pure rye ($1.59 per quart, $.85 per

pint), and various combinations of these brands were marketed as “America’s

Big Four Whiskies” or “America’s Big Six Whiskies”. Old Yock was named for

the Youghiogheny (pronounced "yock-o-henny") River's local nickname, and

perhaps a way to distinguish it from Old Mon-type brands.

Blended whiskey at

that time apparently didn't carry the stigma that it later acquired; notice

that bottom-shelf Tom Keene was the only whiskey not more expensive than the

second-level pure rye. The product line also included Old Yock pure rye ($1.59 per quart, $.85 per

pint), and various combinations of these brands were marketed as “America’s

Big Four Whiskies” or “America’s Big Six Whiskies”. Old Yock was named for

the Youghiogheny (pronounced "yock-o-henny") River's local nickname, and

perhaps a way to distinguish it from Old Mon-type brands.

By the time the distillery finally closed in 1966, they were making a dizzying array of products and brands. Rye, bourbon, corn, blended, and spirit whiskies were part of the portfolio under names like Old Westmoreland (resurrected from Fry & Mathias), Dillinger 60, Old Jolly, Mellow, Look, Mild, Farmer Sam, Rider’s Club, Paddock Club, Light, and Bedford Club.

In addition, Dillinger appears to have been a major producer of whiskey for wholesale trade, supplying whiskey to larger companies for proprietary labeling or blending. Sam Komlenic's collection includes some papers from 1949-1950, which represent...

| "... a request from Joseph Seagram & Son, 7th Street Road, Louisville, 1, Kentucky for four, eight ounce samples of bonded bourbon whiskey from specific barrels entered into the warehouse in 1947; for organoleptic analysis, to be affixed with Kentucky tax stamps (supplied by Seagram) and sent to Seagram. The samples are requested to be “from each day’s production” during four days in March, 1947. The whiskey in these barrels is owned by Distillers Distributing Corporation, a Seagram subsidiary, and they also request information on “the mash bill, proof of distillation, and proof of entry, if available.” Cooperage is listed as “charred,” and “proof” as 109. This was then followed by a transfer of 7,000 gallons of bourbon whiskey in wooden barrels distilled by Meadville Distilleries, Inc., registered distillery No. 19, from I.R.B.W. No. 29 of Dillinger Distilleries to I.R.B.W. No. 36 of Distillers Warehouse Company on Blockdale Avenue in Cheswick, “to be conveyed by truck or rail.” The samples are requested in an “inter office communication” from Dillinger Distilleries dated January 17, 1950, to be sent to “Dillinger Distilleries Inc., Suite 208, 1600 Forbes St., Pittsburgh 13, Pennsylvania – IMMEDIATELY.” This would appear to be a request from the Pittsburgh office that those samples be sent up from the distillery." | ||||

An interesting note here: Sam mentions papers involving both

a request for samples of not-quite-3-year-old whiskey by Joseph Seagram's &

Sons and a transfer of 7,000 gallons of (presumably) finished bourbon

whiskey (assumed to be over four years old) to an address on Blockdale

Avenue in Cheswick.

We have in our collection a bottle labeled "The Blockdale Pure Rye - Allegheny Co. Pennsylvania Whiskey"; Cheswick is

located in Allegheny county. So is Aladdin and Schenley. The Blockdale label

has a distinctive trademark, consisting of the name printed in gold on a

solid black circle (probably difficult to forge in those days). Our bottle

of Old Schenley has the exact same type of trademark. And if that weren't

enough, the Old Blockdale was actually distilled by East Penn Distillery,

which is, despite its misleading name, distillery No. 10 in the 23rd

district. Another bottle of whiskey made at that distillery is labeled I. W.

Harper -- a Schenley brand. So little old Ruffsdale Distillery was supplying

rye whiskey to at least two of the major national brands in the early 1950s.

We have in our collection a bottle labeled "The Blockdale Pure Rye - Allegheny Co. Pennsylvania Whiskey"; Cheswick is

located in Allegheny county. So is Aladdin and Schenley. The Blockdale label

has a distinctive trademark, consisting of the name printed in gold on a

solid black circle (probably difficult to forge in those days). Our bottle

of Old Schenley has the exact same type of trademark. And if that weren't

enough, the Old Blockdale was actually distilled by East Penn Distillery,

which is, despite its misleading name, distillery No. 10 in the 23rd

district. Another bottle of whiskey made at that distillery is labeled I. W.

Harper -- a Schenley brand. So little old Ruffsdale Distillery was supplying

rye whiskey to at least two of the major national brands in the early 1950s.

As

the number of Pennsylvania rye distilleries continued to decline, by the mid

1960s Dillinger whiskey may have filled the bottles of a surprising number

of its deceased brethren.

As

the number of Pennsylvania rye distilleries continued to decline, by the mid

1960s Dillinger whiskey may have filled the bottles of a surprising number

of its deceased brethren.

But it's 2004 now, and as we drive among the ridges

along Highway 31 we see the tall concrete smokestack miles before we arrive

in Ruff’s Dale. There can be no doubt that there is (or at least was) a

distillery here. Past Schaeffer's store and up Church Street to where

Dillinger Drive meets the railroad tracks, and there it is.

As distillery

ruins go, Dillinger’s is in pretty good shape. Abandoned for nearly forty

years, it’s not much worse off than the Old Taylor distillery in Kentucky;

in some ways, it’s even better. For example, the site looks much brighter.

That’s partially due to the fact that the black mold common to distilleries

has long since died off, replaced by what Sam calls “the largest stand of

old-growth poison ivy” he’s ever seen. And partially it’s due to the fact

that many of the side buildings have simply crumbled away. But a lot has to

do with the fact that the current owners, a local commercial real estate

company, have painstakingly kept the site cleaned up over the years. As we

walk around the perimeter, taking pictures, we can see that the shrubbery is

kept cut back (except for the poison ivy, which we later will learn is left

to discourage intruding kids), and behind the chain link fence the internal

driveways are all clear. There is a gate in the fence, and just as we’re

about to walk around the back corner, we see a pickup truck stop at the

gate.

As distillery

ruins go, Dillinger’s is in pretty good shape. Abandoned for nearly forty

years, it’s not much worse off than the Old Taylor distillery in Kentucky;

in some ways, it’s even better. For example, the site looks much brighter.

That’s partially due to the fact that the black mold common to distilleries

has long since died off, replaced by what Sam calls “the largest stand of

old-growth poison ivy” he’s ever seen. And partially it’s due to the fact

that many of the side buildings have simply crumbled away. But a lot has to

do with the fact that the current owners, a local commercial real estate

company, have painstakingly kept the site cleaned up over the years. As we

walk around the perimeter, taking pictures, we can see that the shrubbery is

kept cut back (except for the poison ivy, which we later will learn is left

to discourage intruding kids), and behind the chain link fence the internal

driveways are all clear. There is a gate in the fence, and just as we’re

about to walk around the back corner, we see a pickup truck stop at the

gate.

The driver gets out and unlocks the big padlock, and before he has a

chance to climb back into the truck we call out to him.

The driver gets out and unlocks the big padlock, and before he has a

chance to climb back into the truck we call out to him.

His name is Daryl Shoaf and his uncle owns the real estate company and this site. Daryl is here today for a periodic check and to pick up a couple of tools needed at another site. He’s not accustomed to being stopped by strangers on a sightseeing pilgrimage who beg him to let them in and show them around. And no one would have been prepared for the amount of Sam’s knowledge and familiarity. Let’s face it, your normal group of thieves trying to case a potential burglary target rarely bothers to memorize the company’s annual production figures from 1944. So after several minutes of exposure to Sam’s old-home stories and name-and-place-dropping, and “whatever happen to ol’…?”, and “Y’remember that bar out past where the old gas station used to be?”, Daryl comes to the conclusion that we're all right… well, at least Sam's all right and that's good enough. He lets us come in through the gate, and then proceeds to escort us on a grand tour of Dillinger Distilling (also known as Ruffsdale Distilleries)

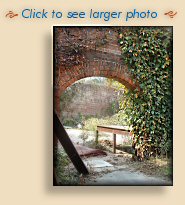

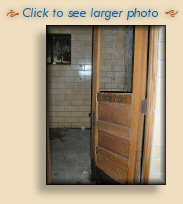

It's not just the grounds outside that

have been cleaned up. As we enter a building, John is at first surprised

that it isn't dark and dingy. Well, not dark anyway.

Quickly after that,

John sees why it's not dark... there isn't any roof. Other parts of the

building, however, are pitch black outside the glow of Daryl's flashlight.

And the corrosion and decomposition lend even more of a cave-like feeling.

Three floors up, Daryl points his lamp at the ceiling (which will be the

floor when we get up there).

Quickly after that,

John sees why it's not dark... there isn't any roof. Other parts of the

building, however, are pitch black outside the glow of Daryl's flashlight.

And the corrosion and decomposition lend even more of a cave-like feeling.

Three floors up, Daryl points his lamp at the ceiling (which will be the

floor when we get up there).

The structural joists are easy to make out, as

the concrete sags clearly between them. "Be sure to walk on the beams when

we're up there," he warns.

The structural joists are easy to make out, as

the concrete sags clearly between them. "Be sure to walk on the beams when

we're up there," he warns.

There is, of course, no equipment here. Not even rusty junk. All of that was removed decades ago. But as we proceed throughout the enormous vacant rooms, with most of the yellow ceramic tile still clinging to the walls, we can see, in Sam's words, the outline of the distilling process: here is a steam line headed for the bottom of the column still openings; over there the boiler placements near the stack; the door to the laboratory; some offices. Here's a washroom, with a urinal that might even be worth something to an antique dealer. The toilet won't be, though. It's been blown to smithereens.

"Kids with M-80's," suggests Daryl. He points at some spray-painted graffiti on the wall as evidence.

"I do what I can, but they'll always

find a way to break in. See here where they got in through this window?

I

just blocked that up awhile ago." Every time Daryl visits the site he makes

sure all the locks are locked and all the accessible windows have

cinderblock walls behind them to prevent entrance. In this case, entrance

had meant the intruders had to scale a two-story wall and approach the

window across the tarred roof.

I

just blocked that up awhile ago." Every time Daryl visits the site he makes

sure all the locks are locked and all the accessible windows have

cinderblock walls behind them to prevent entrance. In this case, entrance

had meant the intruders had to scale a two-story wall and approach the

window across the tarred roof.

"Guess I'll have to put something up to keep 'em off the roof," Daryl notes in his mental to-do book. "That roof isn't safe to walk on and I sure wouldn't want anyone to get hurt." The poison ivy, he says, was left in place purposely because it discourages kids from climbing wherever it exists. The ivy loves it. Huge arms of it reach in through the broken window glass four stories up and extend inside for yards along the ceiling.

Comparing the distillery as it was in

1966 with photos of the original, Sam points out where some of the old

building, located in the rear, seems to have been incorporated into the

upgrades made in the early 1940s and since.

He

says what impresses him the most is the interior of the only standing

warehouse, which is the oldest intact building on the property.

He

says what impresses him the most is the interior of the only standing

warehouse, which is the oldest intact building on the property.

"The framing is absolutely massive: posts and beams on the bottom floor are

about two feet square, and diminish progressively as you ascend through the

building. Each floor is about seven feet high, with approximately 3” X

14” floor framing on 12” centers, covered by a tongue and groove solid

finished floor. The outer construction consists of a stone foundation,

brick walls, and slate roof. Built to last for damn near ever with

minimal maintenance, probably why it’s still there. Add in the three

500 foot deep wells on the ten-acre property, and it can all be yours for

$200,000!"

"The framing is absolutely massive: posts and beams on the bottom floor are

about two feet square, and diminish progressively as you ascend through the

building. Each floor is about seven feet high, with approximately 3” X

14” floor framing on 12” centers, covered by a tongue and groove solid

finished floor. The outer construction consists of a stone foundation,

brick walls, and slate roof. Built to last for damn near ever with

minimal maintenance, probably why it’s still there. Add in the three

500 foot deep wells on the ten-acre property, and it can all be yours for

$200,000!"

Right, Sam. A real "fixer-upper", huh?

We say goodbye to Daryl and head back toward where we're staying tonight in West Mifflin. As we cross the railroad tracks we pass a group of young boys with baseball gloves, just standing around. They seem to be looking for someone to come back with a recovered ball.