American

Whiskey

Rye Distilleries of Eastern

Pennsylvania & Maryland

February 18,

2006 |

|

THE IDEA WAS TO CREATE a spirit that would

have the qualities once thought unique to New England rum. The spirit should be

smooth. Not harsh, as was so often the case with freshly-distilled alcohol. It

should have a richness and complexity that comes from an intimate intermingling

of fermentation congeners and oak barrel wood.

And

above all, it should have a deep rusted amber hue found only in the finest

Cognac… and in New England rum that had returned from many months aboard a

rocking ship, sailing through the tropics and back to Rhode Island.

And

above all, it should have a deep rusted amber hue found only in the finest

Cognac… and in New England rum that had returned from many months aboard a

rocking ship, sailing through the tropics and back to Rhode Island.

Monongahela was close. Certainly close enough,

when New England rum no longer existed and all that people had were their

memories. And for most distillers, that was good enough. For a few, so was outright fraud,

such as adding food coloring and tannic acid to industrial-grade neutral spirits

and

claiming the resulting concoction to be “Aged Rum” or “Pure Rye whiskey”.

and

claiming the resulting concoction to be “Aged Rum” or “Pure Rye whiskey”.

In western Maryland, about halfway between Frederick and the Antietam battlefield, lies the tiny, very picturesque village of Burkittsville. The current population of about 175 people (none of whom, we have been carefully assured, are Blair witches) continues to support no less than three churches, just as they did a century ago. But back then there were also two commercial distilleries in or near here.

One of these was at the Needwood Estate, just

outside of town, where it was founded in the 1840s by Outerbridge Horsey II

(1819-1902), the sort of gentleman whose social circle gave him an opportunity

to sit on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal board of directors and to have been

Maryland's member of the Democratic National Committee for many years. It also

afforded him the ability to produce and market perhaps the most fastidiously

perfect whiskey ever made in America.

One of these was at the Needwood Estate, just

outside of town, where it was founded in the 1840s by Outerbridge Horsey II

(1819-1902), the sort of gentleman whose social circle gave him an opportunity

to sit on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal board of directors and to have been

Maryland's member of the Democratic National Committee for many years. It also

afforded him the ability to produce and market perhaps the most fastidiously

perfect whiskey ever made in America.

The Needwood Distillery produced "Horsey Pure Rye"

and a very special brand called "Golden Gate". Outerbridge Horsey II himself (it's interesting to

speculate on what his friends might have called him, Outie, perhaps? The Big

"O"?) was obsessed with the desire to produce the highest quality spirit ever made,

and to that purpose he traveled to Scotland and possibly Ireland so as to learn

from the masters and to purchase the most modern equipment for the distillery. It was his desire to produce a no-holds-barred, full-tilt-boogie, best-in-class

American whiskey, with no regard as to costs… and priced accordingly, of course.

He piped water down from Catoctin Mountain, and he didn't actually use Maryland

rye, preferring to use either Tennessee or imported Irish rye grain. Even more stunning was his method of

aging his whiskey after distilling. Barrels of "Golden Gate" were routinely loaded aboard ships

and sent around Cape Horn to San Francisco, then returned to Maryland by

railroad train before being bottled. The idea was to capture the months of sloshing about

and the climactic extremes of such a voyage that were the hallmark of the old

New England rums. Horsey wasn’t completely alone in this technique; Sherwood had

a brand of rye that was shipped to Cuba and back (basically the 2nd half of the

triangle itinerary), and King’s Ransom, a scotch produced by a Glasgow

distillery, from whom Horsey learned it, had a special “ ‘Round

the World” edition. In fact, the OTHER distillery in Burkittsville, Ahalt, sent

it’s whiskey to Rio de Janeiro and back as part of its aging process.

It was his desire to produce a no-holds-barred, full-tilt-boogie, best-in-class

American whiskey, with no regard as to costs… and priced accordingly, of course.

He piped water down from Catoctin Mountain, and he didn't actually use Maryland

rye, preferring to use either Tennessee or imported Irish rye grain. Even more stunning was his method of

aging his whiskey after distilling. Barrels of "Golden Gate" were routinely loaded aboard ships

and sent around Cape Horn to San Francisco, then returned to Maryland by

railroad train before being bottled. The idea was to capture the months of sloshing about

and the climactic extremes of such a voyage that were the hallmark of the old

New England rums. Horsey wasn’t completely alone in this technique; Sherwood had

a brand of rye that was shipped to Cuba and back (basically the 2nd half of the

triangle itinerary), and King’s Ransom, a scotch produced by a Glasgow

distillery, from whom Horsey learned it, had a special “ ‘Round

the World” edition. In fact, the OTHER distillery in Burkittsville, Ahalt, sent

it’s whiskey to Rio de Janeiro and back as part of its aging process.

But of course the

real kicker for Horsey was that, once it had landed in San Francisco, his

whiskey then proceeded to travel by rail back across the continent, traveling

through every railroad-served city from San Francisco to Baltimore, with the

brand's name prominently displayed on

the

side of the cases and the train cars. Considering that the railroads in

the 1800s were the elite equivalent of today's jet-set, such identification only

added to the exclusiveness of Horsey Rye Whiskey.

the

side of the cases and the train cars. Considering that the railroads in

the 1800s were the elite equivalent of today's jet-set, such identification only

added to the exclusiveness of Horsey Rye Whiskey.

In his definitive treatise on Maryland rye, newspaperman James Bready notes that Horsey Rye’s clientele extended from Massachusetts to California, but only at the finest hotels and clubs, not at corner saloons.

Needwood Farms still exists – in fact there are multiple examples of estates,

probably pieces of the original,

calling themselves Needwood. None of these appears to be owned by people not in

the National Social Register. The village itself looks like a museum piece, with

each building carefully restored, resulting in what can only be called a scale

model of Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia. We were not able to find even a

trace of either Horsey’s or John Ahalt’s distilleries (although we did find an

Ahalt Road within the village), but the entire village/farm environment made it

clear what sort of operation it must have once been.

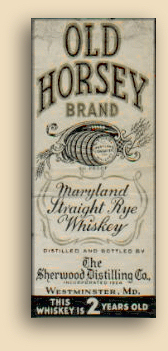

Like so many other wonderful examples of American whiskey, Horsey did not survive national prohibition. Listed in the 1910 Bonfort's industrial register as Maryland Distillery #17, the name reappeared in 1933, but this time as "Old Horsey Very Fine Rye Whiskey", "Old Horsey Maryland Rye Whiskey", and "Old Horsey Rye Whiskey". The word "Old" was added, and also the word "Whiskey", which was a legal requirement after prohibition.

But, of course, it wasn’t the same product. Old

Horsey (the NEW Old Horsey?) was marketed by Sherwood Distillery, itself a

replacement for a once-prominent pre-prohibition whiskey, and was bottled at the

old William Foust distillery in Glen Rock, Pennsylvania. But even before

prohibition, Horsey had fallen victim to the scourge of the Pure Food and Drug

Act of 1906. Superior quality aside, it appears that the new legal

qualifications for labeling a product "pure rye whiskey" caused many a

previously popular brand to suddenly disappear from liquor store shelves. And

after Outterbridge Horsey died in 1902 his heirs shifted half or more of Needwood

Distillery's to corn whiskey and basically vanished from the beverage alcohol

scene.

Distillery, itself a

replacement for a once-prominent pre-prohibition whiskey, and was bottled at the

old William Foust distillery in Glen Rock, Pennsylvania. But even before

prohibition, Horsey had fallen victim to the scourge of the Pure Food and Drug

Act of 1906. Superior quality aside, it appears that the new legal

qualifications for labeling a product "pure rye whiskey" caused many a

previously popular brand to suddenly disappear from liquor store shelves. And

after Outterbridge Horsey died in 1902 his heirs shifted half or more of Needwood

Distillery's to corn whiskey and basically vanished from the beverage alcohol

scene.