American

Whiskey

Woodford Reserve

Distillery

As I mentioned earlier, the Bourbon being distilled here won't be ready to

drink for another three or more years. The whiskey now being sold as Woodford

Reserve was distilled at Brown-Forman's Early Times distillery, in

Louisville.

Trish then led us to the bottling area and showed us how the barrels are

un-filled, over a dumping trough lined with charcoal chips. Here we could

smell the aged whiskey still evident in the empty barrel. We also saw the

tiny bottling line, where the entire production is smaller than the hand-bottled

specialty brands of some other distilleries. Trish showed us sample bottles

of President's Reserve, which comes in a beautiful bottle with a race horse

scene on the back that is seen through the whiskey from the front of the

bottle. Unfortunately, that bottling is available only in Duty-Free stores,

so I'll have to wait until next time I come back from a foreign flight to

be able to buy some.

After boarding the bus we were driven back up the hill to the visitors' center

where we were given peach-flavored ice tea and wonderful Bourbon chocolates.

The tour, the setting, and the product make Labrot & Graham a "must"

tour for anyone interested in how this magnificent liquor is produced.

February

23,

2001:

A

Very

Special

Evening

On July 29, 2000 Labrot & Graham hosted the inaugural dinner and reception

of the newly-formed Kentucky chapter of the American Institute of Wine and

Food at the distillery. The speaker and guest of honor was Julia Child. Building

upon the success of that evening, the distillery began sending invitations

and brochures to select customers and patrons, announcing a whole series

of special events, called the Bourbon & Bluegrass

Series, to be held later that year and into spring of 2001.

There would be a Christmas celebration, a bourbon and chocolate tasting,

cooking classes, and a series of Master Distiller’s Table events, the

first of which would be presented on Friday, February 23rd. Unlike the daily

distillery tours, these events are not free and, although open to the public,

are by reservation only. To learn more, call them at

1-859-879-1812 or write to

Labrot & Graham Distillery

THIS AFTERNOON WE LEAVE from our Lexington motel in what

we expect will be plenty of time to get to the Labrot & Graham distillery for

the special event beginning at 5:30 this evening. We thought we might take a

ride past Stone Castle, the Old Taylor distillery which is not far from Labrot &

Graham, to see if the antique shop there might still be open. The owner, Cecil

Withrow, passed away last December and we thought we might offer our condolences

to his wife. We drive to Versailles, but we just can’t find Elm Street, the road

that becomes McCracken Pike as it heads toward Glenn’s Creek. After driving out

the other side of Versailles and turning around, we drive back to the

intersection at the center of town and take another road. As that one starts

heading off into unfamiliar territory, we turn around and do it all over again.

Back and forth. Around and around. We stop and ask directions (Linda’s idea) (of

course), then follow the directions; then end up right back where we started

from. None of the roads seem to lead past the Catholic school that has always

been our landmark for locating Elm. After a frustrating hour and half of driving

around and around Versailles (never mind Old Taylor; we’re now nearly half an

hour late for the event), Linda finally spots Elm Street. Looking over, John

sees that they’ve remodeled the Catholic school, adding a fence and other

features that has caused us to drive right by several times without noticing it.

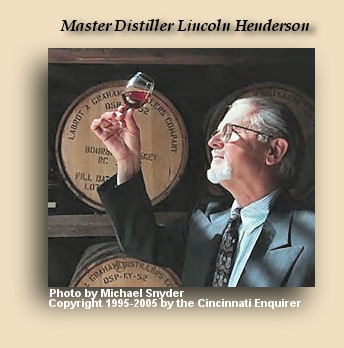

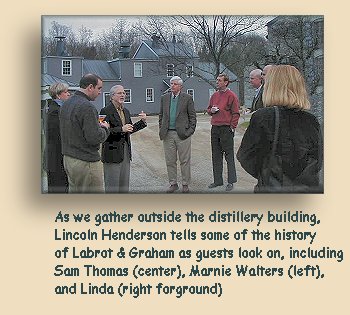

As we enter the Visitor’s Center, we are offered hors d’oeuvres

and bourbon before joining about fifteen other people milling around and

talking with Bill Creason (Labrot & Graham’s general manager and

our host this evening), Dave Scheurich (the plant manager and on-site distiller),

Lincoln Henderson (Brown-Forman’s master distiller), Jimmy Russell (Wild

Turkey’s master distiller), and Sam Thomas (one of Kentucky’s

best-known bourbon historians), Both Jimmy and Lincoln seem to remember us

from times we’ve met them before. Also among the guests is Marnie Walters,

the young woman John spoke to on the phone for reservations, who shares a

very beautiful and unusual name with John’s daughter.

Not long afterward (it’s too bad we were so late, this party itself

must have lasted nearly an hour), Bill announces that the tour is about to

begin. We are encouraged to freshen our drinks and bring them with us. We

board the tour bus that takes guests from the Visitor Center down into the

hollow where the distillery itself lies. After leaving the bus, we assemble

in front of the main distillery building and the tour

commences.

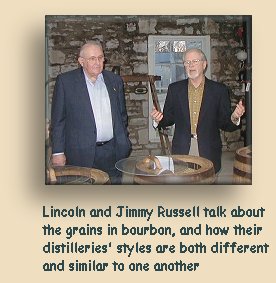

In many ways, of course, the tour is like the normal public tours. After

all, the same things are being covered. But this tour is being presented

with a running commentary by a pair of the most expert tour guides imaginable,

Lincoln Henderson and Jimmy Russell. Having these two gentlemen present the

tour brings out angles and points of view that would never have been touched

without them. In fact, the two of them playing off one another provides insights

that could only have occurred here and now.

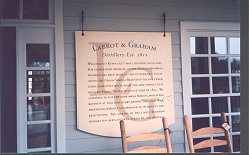

Of course, the tour begins with a discussion of the distillery’s history.

These buildings were originally the Elijah Pepper distillery, the home of

master distiller James Crow. Crow is generally recognized as one of the founding

fathers of the bourbon industry as we know it, and many think of him as the

father of bourbon itself. The distillery passed though several hands before

becoming the Labrot & Graham distillery in 1878, which it remained even

after being sold to Brown-Forman in 1941. In the early 1960’s it was

sold and shut down. It lay abandoned and decaying for years before they bought

it back again and spent nearly ten million dollars restoring it to its current

state. As Lincoln was pointing this out, John mentions Charles K. Cowdery’s

videotape, made in 1991 and aired on Kentucky public television, that shows

scenes of the distillery in its abandonment. Lincoln thanks him for bringing

it up and takes an opportunity to praise Chuck’s

program.

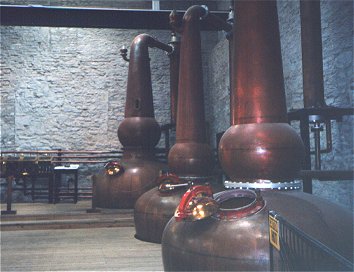

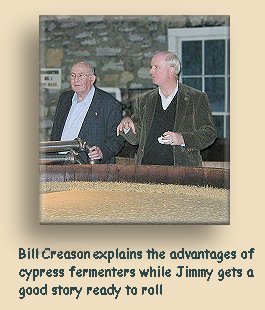

Labrot & Graham is unique among all bourbon distilleries, not only because

of it’s place in bourbon history but also for the three gorgeous copper

pot stills that are it’s heart and soul. Jimmy Russell’s Boulevard

Distillery, better known throughout the world as Wild Turkey, is also steeped

in bourbon history, but his whiskey is distilled in what is known as a

"continuous still". This is the type used by every other bourbon distillery,

and the one at Wild Turkey is a first-class example of that type. There are

many other differences as well, such as who makes their barrels (there are

only two companies; Labrot & Graham uses Bluegrass Cooperage and Wild

Turkey uses Independent Stave Company – and each swears their choice

of barrel is a contributing factor in their success), the exact combination

of corn, rye, and barley malt (they won’t tell, other than to say that

they don’t tell anybody and printed reports they’ve seen are both

fictitious and wrong), and the type of warehouses they use for aging the

bourbon (Labrot & Graham uses unique stone warehouses with controlled

temperature; Wild Turkey uses metal-clad warehouses with natural temperatures).

In fact, nearly everything about their approach to making fine bourbon whiskey

is different between the two, but both agree that the result is still fine

bourbon.

The tour is very much "hands-on". As we observe the mash fermenting in the

cypress tanks, we’re encouraged to breath in the vapors and taste the

mash itself. We can compare and see the difference only a few hours can make

in the fermentation process. We are given samples of the raw white dog whiskey

coming off the stills so we can experience what new bourbon whiskey looks,

smells, and tastes like. As we are introduced to the fine art of barrel

construction, an audience member (who just happens to be Linda) is chosen

to demonstrate the art of whacking the bung into the barrel with a wooden

bung hammer. Feigning concern that she might miss or not hit it hard enough,

Linda suggests that John's head should be placed on the bung as a sort of

guide. She swings the mallet. The imagery must have worked… she splits

that bung right in two!

It is at about this point when John realizes that the batteries in his camera

need to be replaced. No problem; he brought the battery charger and a bag

of freshly charged batteries conveniently located... uh, well, on his dresser

bureau in the bedroom at home. We are less than half an hour into an evening

to remember forever and we have taken our last photograph of this trip. Oh

well. You always have to leave something behind. You can bet it won't

EVER be the batteries again!

In the warehouse we learn about the differences between aging bourbon in

a temperature-controlled stone-walled environment and a naturally-climated

metal-clad one. We are familiar with climate-control as a tool for maturing

bourbon, but until tonight we thought it was a relatively modern invention,

say maybe during or shortly after Prohibition. Not so. We learn that within

only a couple years after its construction in 1838, the need for temperature

control had become quite apparent, because the steady temperatures of the

stone-walled warehouse slowed the aging processes dramatically. A system

of steam pipes was installed which allowed the temperature to be raised as

needed.

After the tour we are taken to another building, where the tasting and dining

area had been set up. Here the pride of both Lincoln (Woodford Reserve

Distiller’s Select) and Jimmy (Russell’s Reserve) will be compared,

not to determine which is "better" but to show how different two expressions

of the distiller’s art can be, as well as how similar two products made

with such different processes can be. The tasting is very informative, and

includes important standards, such as just how much water to use to take

the alcohol edge off (two parts bourbon to one part water). One thing that

seems noteworthy is that neither master distiller appears to be concerned

with naming specific flavors, such as fruits or spices. "Oak"iness, grain

flavors, smoke, tobacco, and leather seem to be about the limit of the

descriptive phrases they both use. And this is certainly not a "see the lecturer"

presentation, either; this is a hands-on tasting for which we are provided

with generous samples of each bourbon and a glass of water.

After the tasting the gourmet dinner is presented. Served elegantly in a

formal style, the meal differs from some we’ve had in that it left us

feeling we’d received the full value of what we paid for. The dinner,

prepared by Labrot & Graham’s own chef-in-residence David Larson,

consists of:

There are only a small number of tables, with one of the celebrities or

distillery executives seated at each to share with the guests. As at Mary

Bobo’s in Lynchburg (where our table’s hostess was Lynn Tolley

herself), we again find ourselves in the enviable position of sharing a table

with only one other guest (a knowledgeable man from Japan; unfortunately each

of us believes the other has written down his name) and Lincoln Henderson.

Needless to say, the conversation is awesome.

As we finish dinner, historian Sam Thomas, with the assistance of the two

master distillers, presents a talk on the History of Bourbon in Kentucky.

Of course, such a discussion, given at this particular location, would almost

have to focus on the legend of Doctor James C. Crow, and whether he deserves

the often-given title of "Father of Bourbon Whiskey". According to Sam, like

all such legends, there is some truth, accompanied by what appears to be

more than just a little "knowledge" of questionable merit. Sam carefully

lays out some of the claims about Crow and points out discrepancies in the

documented record. Of particular concern to Sam is the fact that little of

what has been published about James Crow appears to have been written during

his lifetime, or by people who actually knew the man. As this is very much

a two-way discussion, with the guests encouraged to participate, John offers

the idea that the real "Father of Bourbon" (at least of the

federally-acknowledged definition of bourbon) might have been Edmund Taylor,

who documented both ingredients and processes and successfully lobbied them

into the Bottled-In-Bond Act. His ideas of what a "quality bourbon product"

should be would have come directly from his association with James Crow,

and perhaps it was THAT that raised Dr. Crow’s methods to the status

of Authority. Sam entertains that idea for awhile and never really really

indicates disagreement with it. It also emphasizes the direction he is

illustrating.

After the discussion, Bill Creason brings the event to a close with thank

yous and hints of more to come, and we head back to the motel in Lexington.

Our drive back sure is a lot shorter than getting there .

September 17 - 20,

1998 -- The Kentucky

Bourbon

Festival

once known as

Labrot

& Graham

And before that, Oscar Pepper

Versailles,

Kentucky

The really, truly oldest Kentucky

bourbon distillery.

On

Saturday morning, our friends Bruce and Amy learned they had to go back home

earlier than planned, so we weren't able to share the trip out to the Labrot

& Graham distillery with

them.

Linda and I drove out the Bluegrass Parkway toward Lexington and Versailles

(which is pronounced "Vur-Sails", not "Vair-Sigh" like in France) by ourselves

this morning. We drove for miles among breathtakingly beautiful horse farms,

inhabited by some of the most famous equines in the world (and also many

of the less-famous, but far more commonly observed Kentucky Thoroughbred

Racing Cows!). Earlier this year, Linda's father Joe Teterus and I took a

trip to visit Labrot & Graham and we were very impressed. It was my

father-in-law's first trip to a Bourbon distillery and there couldn't have

been a better introduction.

On

Saturday morning, our friends Bruce and Amy learned they had to go back home

earlier than planned, so we weren't able to share the trip out to the Labrot

& Graham distillery with

them.

Linda and I drove out the Bluegrass Parkway toward Lexington and Versailles

(which is pronounced "Vur-Sails", not "Vair-Sigh" like in France) by ourselves

this morning. We drove for miles among breathtakingly beautiful horse farms,

inhabited by some of the most famous equines in the world (and also many

of the less-famous, but far more commonly observed Kentucky Thoroughbred

Racing Cows!). Earlier this year, Linda's father Joe Teterus and I took a

trip to visit Labrot & Graham and we were very impressed. It was my

father-in-law's first trip to a Bourbon distillery and there couldn't have

been a better introduction.

Linda didn't go on that tour, so I was glad that

she could be here this time. Labrot & Graham, in the heart of Woodford

County, has been beautifully restored on the site of what is perhaps the country's

oldest bourbon distillery, built by Elijah Pepper in 1812. It was originally known

as the Oscar Pepper Distillery when Dr. James Crow worked here in the 1820's

and '30s. And it was during this time that the pharmacist from Scotland

developed the methods that would later become the basis for the legal definition

of straight bourbon whiskey. Later the plant became one of the group

of Glenn's Creek distilleries operated by Colonel Edmund H. Taylor (see the

Ghosts of Distilleries Past

page for more details). Leopold Labrot and James Graham purchased it

in 1878 and produced whiskey there (except during Prohibition) until 1941. Wartime

restrictions pretty much did L&G in, and the facilities were sold to

Brown-Forman. They operated it until 1968 and then sold it in 1971.

According to master distiller Lincoln Henderson, in 1994 Brown-Forman, while

searching throughout several states for a location to "start up an old

distillery with a lot of heritage", they re-discovered their old property and

re-purchased it.

Linda didn't go on that tour, so I was glad that

she could be here this time. Labrot & Graham, in the heart of Woodford

County, has been beautifully restored on the site of what is perhaps the country's

oldest bourbon distillery, built by Elijah Pepper in 1812. It was originally known

as the Oscar Pepper Distillery when Dr. James Crow worked here in the 1820's

and '30s. And it was during this time that the pharmacist from Scotland

developed the methods that would later become the basis for the legal definition

of straight bourbon whiskey. Later the plant became one of the group

of Glenn's Creek distilleries operated by Colonel Edmund H. Taylor (see the

Ghosts of Distilleries Past

page for more details). Leopold Labrot and James Graham purchased it

in 1878 and produced whiskey there (except during Prohibition) until 1941. Wartime

restrictions pretty much did L&G in, and the facilities were sold to

Brown-Forman. They operated it until 1968 and then sold it in 1971.

According to master distiller Lincoln Henderson, in 1994 Brown-Forman, while

searching throughout several states for a location to "start up an old

distillery with a lot of heritage", they re-discovered their old property and

re-purchased it.

They

also spent over seven million dollars to refurbish and restore the old landmark,

ending up with one of the most beautiful settings in the industry.

They

also spent over seven million dollars to refurbish and restore the old landmark,

ending up with one of the most beautiful settings in the industry.

We

met our tour guide, Trish, at the bus outside the visitor's center. She drove

us down to where the production area is, past the man-made lake which serves

as an attractive sight, a pleasant lunchtime diversion (it's stocked with

fish), and (not incidentally) a source of emergency water to ensure that

the fate of Heaven Hill is not repeated at L&G. The Labrot & Graham

tour is the most complete of any we've been on recently, covering everything

in the process. What is most remarkable, however, is just how small everything

is in comparison with other operations. As Trish took us through the fermenting

room, hardly larger than Linda's father's barn, we looked at the brand new

cypress fermenting tanks and the single stainless steel cooking tank and

marveled at how small everything is.

We

met our tour guide, Trish, at the bus outside the visitor's center. She drove

us down to where the production area is, past the man-made lake which serves

as an attractive sight, a pleasant lunchtime diversion (it's stocked with

fish), and (not incidentally) a source of emergency water to ensure that

the fate of Heaven Hill is not repeated at L&G. The Labrot & Graham

tour is the most complete of any we've been on recently, covering everything

in the process. What is most remarkable, however, is just how small everything

is in comparison with other operations. As Trish took us through the fermenting

room, hardly larger than Linda's father's barn, we looked at the brand new

cypress fermenting tanks and the single stainless steel cooking tank and

marveled at how small everything is.

The starring

feature of Labrot & Graham, however is something you simply cannot find

anywhere else in America. In the next room from the fermenting tanks, standing

in a corner of the lovely stone building, are three beautiful all-copper

pot stills of the type used in making Scotch and Irish whiskies, but not

for Bourbon in decades. The whiskey being distilled from these pot stills

is still aging and won't be available to drink until 2001 or later. But as

she led us through the area where the barrel exhibit is displayed, Trish

showed us a glass of pure, clear "white dog" right off the still. In fact,

she passed it around for everyone to get a real close-up look and smell (at

140 proof, no one had the nerve to taste it, though). Trish also showed us

cutaway views of actual whiskey barrels in various states of char and age,

and also how they are made and filled. Then she took us into the warehouse

where this wonderful liquor is stored for four to eight years. We saw a barrel

signed by Owsley Brown II (Brown-Forman president) and another signed by

the governor of Kentucky. Trish pointed out that we could purchase our own

full barrel (53 gallons) for as little as $6,000 -- she also mentioned that

she has a birthday coming up later this month, in case anyone might be interested

in a gift.

The starring

feature of Labrot & Graham, however is something you simply cannot find

anywhere else in America. In the next room from the fermenting tanks, standing

in a corner of the lovely stone building, are three beautiful all-copper

pot stills of the type used in making Scotch and Irish whiskies, but not

for Bourbon in decades. The whiskey being distilled from these pot stills

is still aging and won't be available to drink until 2001 or later. But as

she led us through the area where the barrel exhibit is displayed, Trish

showed us a glass of pure, clear "white dog" right off the still. In fact,

she passed it around for everyone to get a real close-up look and smell (at

140 proof, no one had the nerve to taste it, though). Trish also showed us

cutaway views of actual whiskey barrels in various states of char and age,

and also how they are made and filled. Then she took us into the warehouse

where this wonderful liquor is stored for four to eight years. We saw a barrel

signed by Owsley Brown II (Brown-Forman president) and another signed by

the governor of Kentucky. Trish pointed out that we could purchase our own

full barrel (53 gallons) for as little as $6,000 -- she also mentioned that

she has a birthday coming up later this month, in case anyone might be interested

in a gift.

Master distiller Lincoln Henderson personally selected the

first 3,000 barrels of prime, seven and a half year old Old Forester stock

for the first Labrot and Graham bottlings, and that is the stock that is

currently being aged and bottled

here.

Master distiller Lincoln Henderson personally selected the

first 3,000 barrels of prime, seven and a half year old Old Forester stock

for the first Labrot and Graham bottlings, and that is the stock that is

currently being aged and bottled

here. When I asked her, Trish said that they are quite proud of the Woodford Reserve

name and the acceptance it has received, and she doesn't imagine that they

will discontinue the brand, even though they will be adding brands made from

what's being distilled and aged here now. That confirmed what Chris Morris

said when I asked him about the Labrot & Graham brands -- that they have

plans for several different Bourbons to be made at the new facility, in addition

to Woodford Reserve.

When I asked her, Trish said that they are quite proud of the Woodford Reserve

name and the acceptance it has received, and she doesn't imagine that they

will discontinue the brand, even though they will be adding brands made from

what's being distilled and aged here now. That confirmed what Chris Morris

said when I asked him about the Labrot & Graham brands -- that they have

plans for several different Bourbons to be made at the new facility, in addition

to Woodford Reserve.

7855 McCracken Pike

Versailles, Kentucky 40383

We

arrive at Labrot & Graham frustrated and embarrassed, only to discover that

they’ve wisely allowed some lead time and we aren’t too late after all. In fact,

there will be others who will arrive after us.

We

arrive at Labrot & Graham frustrated and embarrassed, only to discover that

they’ve wisely allowed some lead time and we aren’t too late after all. In fact,

there will be others who will arrive after us.

So, as we progress through the distillery, we learn

how the whiskey here is made, as well as how that’s different from the

way it’s made at Wild Turkey. The friendly competitors augment each

other’s comments and the result is an unbelievably rich experience for

those of us with a greater-than-average curiosity about such things.

So, as we progress through the distillery, we learn

how the whiskey here is made, as well as how that’s different from the

way it’s made at Wild Turkey. The friendly competitors augment each

other’s comments and the result is an unbelievably rich experience for

those of us with a greater-than-average curiosity about such things.

This allowed more than one hot-cold cycle per year and thus

allowed very accurate control of the aging process. Jimmy Russell pointed

out that the extreme variations obtainable in a metal-clad warehouse also

have their advantages, and that those are made use of in producing Wild Turkey

bourbon. We didn’t mention to anyone, but we know at least some Wild

Turkey bourbon is currently aging away in brick warehouses. It’s not

likely that they’re climate-controlled, though.

This allowed more than one hot-cold cycle per year and thus

allowed very accurate control of the aging process. Jimmy Russell pointed

out that the extreme variations obtainable in a metal-clad warehouse also

have their advantages, and that those are made use of in producing Wild Turkey

bourbon. We didn’t mention to anyone, but we know at least some Wild

Turkey bourbon is currently aging away in brick warehouses. It’s not

likely that they’re climate-controlled, though.

![]()