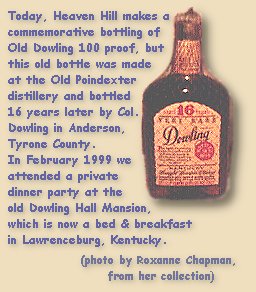

|

American

Whiskey

|

|

In February of 1999, we took another excursion into America's bourbon county. This time we came in through the back yard, where all the old discarded things lay. We were looking for the ghosts of some of Bourbon's true legends, and we found some. Taking the scenic route along the northern banks of the Ohio river, we stopped briefly at New Richmond to see the marker that shows how incredibly high the river has risen during several floods. We also spent a few minutes driving the wrong direction around Ripley and Aberdeen, before crossing the bridge into Kentucky at Maysville. Maysville was the Ohio riverport for the Frankfort/Lawrenceburg/Lexington area of what was then all known as Bourbon County. Along with Louisville (then called Ohio Falls), and Owensboro, Maysville served to define the limits of just where "Bourbon" was. And although it's no longer important as a shipping point, geographically it still does.

Old

Crow

Distillery

Staying on the scenic route, we drove through Thoroughbred horse country

around Lexington and into Georgetown. Known as Lebanon at the time, it was

here that the Reverend Elijah Craig, popularly (although probably erroneously)

credited with being the father of Bourbon Whiskey, made whiskey at his fulling

mill in 1789 and it was also here

that Henry Hudson

Wathen was known to have operated a distillery a year earlier in

1788. There were no Cracker Barrel restaurants here at that time, but we

found one today and had lunch there, before heading on toward Frankfort.

Along the way we saw the Jim Beam facility at the Forks of the Elkhorn River.

Only the warehouses and loading docks are used now, but the empty distillery

buildings once held the heart of National Distillers Corporation. This was

once the home of Old Grand Dad, Bourbon DeLuxe,

Dr. Crow never actually owned a distillery, though. The enormous Old Crow

distillery which sits on Glenn's Creek today was built around 1872, 16 years

after he died. Old Crow whiskey was made here, in essentially the exact same

way, until Prohibition, and then again after Repeal. National Distillers

owned it then, but they had made no changes in the way the bourbon was made.

Then, sometime during the 1960's, the plant was refurbished and formula was

changed. The new version was different, and there was some public outcry,

but National continued to use it until they were purchased by Jim Beam Brands

in

1987.

Two decades after James Crow's death, the second "father" of Bourbon began

his work, also here along Glenn's Creek. Colonel Edmund H. Taylor began his

distillery-owner's career at the O.F.C. distillery in Leestown (which later

became Ancient Age and after that, Buffalo Trace). After turning over ownership to his partner George T.

Stagg, Taylor built a new distillery on Glenn's Creek. It has been called

one of the most remarkable sights in the bourbon industry. The main distillery

building is made entirely of limestone blocks, in the form of a medieval

castle, complete with turrets. A drawing of the castle appears on the label

of Old Taylor Bourbon.

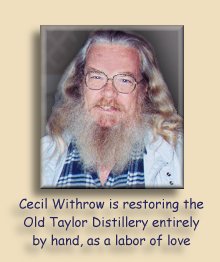

We’d read earlier that the Old Taylor place, which is built in the style

of a stone castle, had been purchased by an ex-employee of Old Crow, who

has opened a museum and has also produced a very small amount of bourbon

which he is scheduled to release this year.

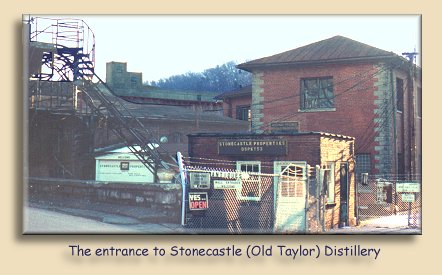

We were surprised to find Old Taylor located literally right next door to the Old Crow place. In fact, they appear to have shared some warehouses and, according to Cecil Withrow, the bearded, white-haired ex-boilermaker who now owns it, they even shared production facilities at one time. Cecil is a collector with a special fascination for Old Crow and Old Taylor. He has lots of Crow decanters, pictures, bottles, and other memorabilia. Oh, yes, and a distillery! He told us he is indeed ready to bottle some product (purchased, not produced) but he doesn’t have it together yet. Meantime, he’s slowly restoring the distillery. He showed us photos of the main building where most of the restoration has been done. It's really beautiful. There is also a restaurant scheduled to open this spring.

We spent most of our time (we will be back for a more thorough

tour) in the main bottling room, which Cecil has divided up into museum-like

displays and flea-market booths, mostly dedicated to whiskey memorabilia. We

spent a long, fascinating time there and

From Stonecastle/Old Taylor we continued down Glenn’s Creek Road, as it became McCracken Pike and passed Labrot & Graham, then drove on through Versailles toward Lawrenceburg. We passed Wild Turkey Distillery in Tyrone along the way.

|

|

2015

UPDATE: Much has happened to the Old Taylor castle in the years since we visited in 1999. Cecil Withrow passed away in December of the next year and, after sitting abandoned for well over a decade after that, the site was purchased by Will Arvin and Wes Murray of Peristyle, LLC in May of 2014. As of September 2015, plans to restore the distillery in its entirety are beginning to bear fruit, and the NEW Old Taylor Distillery (if they will be able to call it that, since the Sazerac company now owns the Old Taylor brand) is expected to be open to the public in the spring of 2016. We expect to visit the completed distillery then, but in the meantime you can read more about it HERE, and HERE. |

|

The

Old Fire Copper Distilling

Company

The National Distilling Company

(Old Grand

Dad)

The

Old Crow Distilling

Company

The

Labrot &

Graham Distilling Company

The Ripy Brothers' Tyrone Distilling

Company

The J.T.S. Brown Distilling Company

The Old Joe Distilling Company

The Old Prentice Distilling

Company

|

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright ©1999 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|

Sunny Brook, and others. Old Grand Dad and Bourbon

Deluxe still exist, but the whiskey in the bottles is Jim Beam whiskey now.

Sunny Brook, and others. Old Grand Dad and Bourbon

Deluxe still exist, but the whiskey in the bottles is Jim Beam whiskey now.

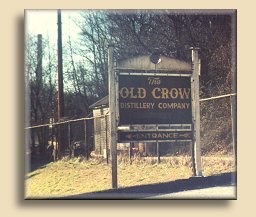

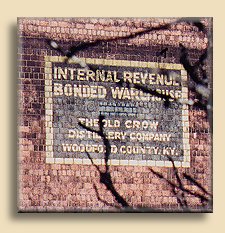

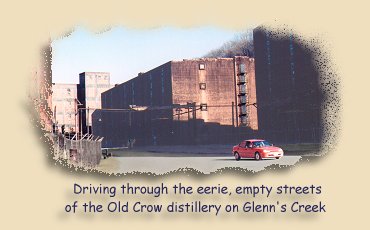

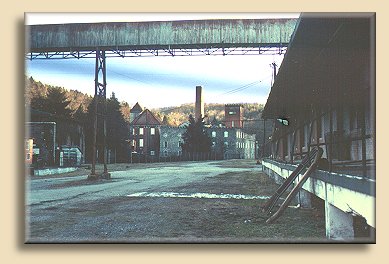

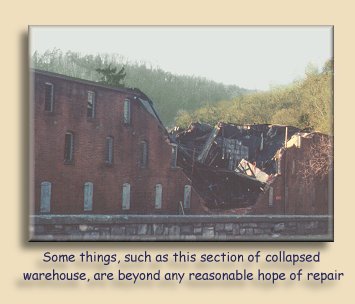

We drove down twisty Glenn’s Creek road, looking for traces

of the ruins of the old place. When we found it we were shocked at how big

the place is. Distilleries tend to look pretty cruddy anyway, with the black

fungus that likes to grow on the warehouses, but when combined with buildings

that have been abandoned for ten or fifteen years it looks even worse. Still,

it wasn’t the hardly-identifiable crumbled ruins we’d anticipated.

We sat outside the gate for only a few minutes, getting the cameras out,

before a security car (marked "Jim Beam") pulled up and, after making sure

we were not a trespassing threat, a nice lady told us about the distillery

and also about the Old Taylor distillery down the road. She suggested some

good places for taking photos.

We drove down twisty Glenn’s Creek road, looking for traces

of the ruins of the old place. When we found it we were shocked at how big

the place is. Distilleries tend to look pretty cruddy anyway, with the black

fungus that likes to grow on the warehouses, but when combined with buildings

that have been abandoned for ten or fifteen years it looks even worse. Still,

it wasn’t the hardly-identifiable crumbled ruins we’d anticipated.

We sat outside the gate for only a few minutes, getting the cameras out,

before a security car (marked "Jim Beam") pulled up and, after making sure

we were not a trespassing threat, a nice lady told us about the distillery

and also about the Old Taylor distillery down the road. She suggested some

good places for taking photos.

In

1823, a gentleman physician, Dr. James Crow, arrived in the area. A man

apparently trying to escape from a less-than-completely-responsible past

(involving bankruptcy and abandonment), Crow was beginning to get his new

life in order when he went to work for Colonel Willis Field, a distiller

on Grier's Creek near Woodford County. Crow brought his scientific and medical

training to what had been a very rough-and-tumble process and the results

were astounding. He was able to achieve a consistency of quality never before

imagined, one which would give a distiller the ability to make production

commitments that could actually be met. Dr. Crow soon moved to the town of

Millville on Glenn's Creek and for the next twenty years he was in charge

of the Oscar Pepper Distillery (later to become Labrot & Graham) on McCracken

Pike. Later he went to work for the Johnson Distillery a couple miles north

on Glenn's Creek Road. That distillery later became Old Taylor. He worked

there until his death in 1856. Because of his development of methods that

would ensure continuity and consistent quality (including the use of measuring

devices and the knowledge of how the sour-mash process actually works) many

consider Dr. James Crow to be the true father of Bourbon.

In

1823, a gentleman physician, Dr. James Crow, arrived in the area. A man

apparently trying to escape from a less-than-completely-responsible past

(involving bankruptcy and abandonment), Crow was beginning to get his new

life in order when he went to work for Colonel Willis Field, a distiller

on Grier's Creek near Woodford County. Crow brought his scientific and medical

training to what had been a very rough-and-tumble process and the results

were astounding. He was able to achieve a consistency of quality never before

imagined, one which would give a distiller the ability to make production

commitments that could actually be met. Dr. Crow soon moved to the town of

Millville on Glenn's Creek and for the next twenty years he was in charge

of the Oscar Pepper Distillery (later to become Labrot & Graham) on McCracken

Pike. Later he went to work for the Johnson Distillery a couple miles north

on Glenn's Creek Road. That distillery later became Old Taylor. He worked

there until his death in 1856. Because of his development of methods that

would ensure continuity and consistent quality (including the use of measuring

devices and the knowledge of how the sour-mash process actually works) many

consider Dr. James Crow to be the true father of Bourbon.

The man who became the new master distiller, William

Mitchell, had worked directly with Crow and knew all his methods. His

continuation of Old Crow whiskey was identical to the original. He in turn

taught this to his own successor, Van Johnson.

The man who became the new master distiller, William

Mitchell, had worked directly with Crow and knew all his methods. His

continuation of Old Crow whiskey was identical to the original. He in turn

taught this to his own successor, Van Johnson.

The

castle wasn't just a facade, either; inside were gardens and ornate rooms

where Colonel Taylor used to entertain important government officials and

politicians. Taylor's contribution was the guarantee of quality in an industry

that had lost nearly all credibility. Very few distillers were selling quality

product, and virtually none of what good bourbon was being made ever got

to the public without being diluted, polluted, and rectified. Edmund Taylor

crusaded tirelessly to have laws passed that would ensure quality product,

and he was successful. He was the originator of what became known as the

Bottled-in-Bond act of 1897. This was essentially a federal subsidy by tax

deferral for product made to strict government standards and stored under

government supervision. In the process, he was responsible for documenting

what those standards would be. And therefore, Edmund H. Taylor, Jr. was given

the task of defining Straight Bourbon Whiskey. As a result of the success

of this act, other federally enforced standards for food products were enacted,

and we can say we owe much of our current standards in many consumable products

to this gentleman with a distillery on Glenn's Creek.

The

castle wasn't just a facade, either; inside were gardens and ornate rooms

where Colonel Taylor used to entertain important government officials and

politicians. Taylor's contribution was the guarantee of quality in an industry

that had lost nearly all credibility. Very few distillers were selling quality

product, and virtually none of what good bourbon was being made ever got

to the public without being diluted, polluted, and rectified. Edmund Taylor

crusaded tirelessly to have laws passed that would ensure quality product,

and he was successful. He was the originator of what became known as the

Bottled-in-Bond act of 1897. This was essentially a federal subsidy by tax

deferral for product made to strict government standards and stored under

government supervision. In the process, he was responsible for documenting

what those standards would be. And therefore, Edmund H. Taylor, Jr. was given

the task of defining Straight Bourbon Whiskey. As a result of the success

of this act, other federally enforced standards for food products were enacted,

and we can say we owe much of our current standards in many consumable products

to this gentleman with a distillery on Glenn's Creek.

Well,

maybe a couple of distilleries. Actually, Colonel Taylor owned or had an interest

in several plants, including the Pepper distillery and Frankfort distillery,

and even the Stagg distillery in Leestown was actually known as the E.H. Taylor

Jr. Company. Edmund Taylor remained a very powerful figure in the bourbon

industry well into the twentieth century. He died, at the age of 90, in 1922.

Well,

maybe a couple of distilleries. Actually, Colonel Taylor owned or had an interest

in several plants, including the Pepper distillery and Frankfort distillery,

and even the Stagg distillery in Leestown was actually known as the E.H. Taylor

Jr. Company. Edmund Taylor remained a very powerful figure in the bourbon

industry well into the twentieth century. He died, at the age of 90, in 1922.

We had expected the place, now called Stone Castle Distillery

to be a couple miles or so down the road, so we were very surprised to find

that the large expanse of sheds and whiskey warehouses through which

Glenn’s Creek Road winds included both distilleries.

We had expected the place, now called Stone Castle Distillery

to be a couple miles or so down the road, so we were very surprised to find

that the large expanse of sheds and whiskey warehouses through which

Glenn’s Creek Road winds included both distilleries.

bought

a couple nice items. We got a Kentucky Tavern decanter with the name written in

gold on the glass and we got a Jack Danielís Barrelhouse No. 1 bottle, complete

with tag and wooden case. That was priced at $18.00 but Cecil let us have it for

even less. We later saw those bottles in nearly identical condition selling for

nearly one hundred dollars.

bought

a couple nice items. We got a Kentucky Tavern decanter with the name written in

gold on the glass and we got a Jack Danielís Barrelhouse No. 1 bottle, complete

with tag and wooden case. That was priced at $18.00 but Cecil let us have it for

even less. We later saw those bottles in nearly identical condition selling for

nearly one hundred dollars.