American

Whiskey

Similarities and

Differences

SIMILARITIES and DIFFERENCES is the method of understanding and

appreciating something by learning to recognize it's unique qualities. To

do that, you must first understand what it IS, by seeing how it fits into

a group with other similar things. And then you must learn to distinguish

what it ISN'T by noting how it differs from the others in that group.

Even though we're probably not aware of it, that's the basis for how we learn

to really understand everything in the world around us. We ask ourselves...

Of course, most of us aren't looking for an in-depth understanding of

everything in world around us. We're very selective about what to

pay that much attention to. Take mayonnaise, for example. Most of us enjoy

the condiment, and we might even have a favorite brand. But it's not likely

that we would travel long distances to spend a day at the Hellman's/BestFoods

plant or Kraft or any of the smaller plants that produce Kroger, Winn-Dixie,

Food Lion or whatever mayonnaise. Nor are most of us particularly interested

in the history of mayonnaise in America. Okay, now before we start receiving

lots of angry email from hitherto-unknown-to-us mayonnaise aficionados,

the same can be said of anything... including our beloved bourbon whiskey.

For all we know, there may be a mayonnaise Academy going on at Heinz this

very moment and if so, please accept our apology for choosing that product

as our example.

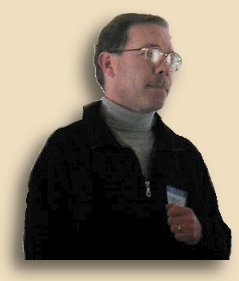

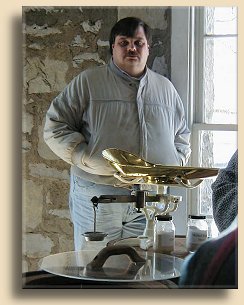

Chris Morris, recent successor to Lincoln Henderson as the Master Distiller

for Brown-Forman distilleries, understands the process of making bourbon

very well. And he understands the process of conveying that information to

the rest of us even better. At 45, Chris has an extraordinary background

in bourbon, and alcohol beverages in general (before taking over as bourbon

guru, he was Marketing Director and Brand Manager for Don Eduardo and Pepe

Lopez tequilas). Both of his parents worked at Brown-Forman and, starting

while still in high school ("..my dad came home and announced that I was

an intern"), Chris has been employed in the liquor industry for over 26 years.

During this time, he has been associated with more distilleries in Kentucky

and Tennessee (ten of them) than anyone else in the industry. Before being

selected as Lincoln’s protégé, Chris served as marketing

director and company historian. If you take the

online virtual tour

of the distillery offered at the Early

Times web site, it will be Chris who guides you through many of the same

steps we will go through today.

He is joined today by our old friend (well, he’s not so old, but he

is our friend) Michael Veach. Mike is an historian with a Masters

degree in History from the University of Louisville and an avid interest

in the Kentucky bourbon (both historical and gastronomical). Mike has

served as historical consultant for the Buffalo Trace and Heaven Hill

distilleries, and also for Brown-Forman, where he and Chris became friends

and colleagues in the study of American whiskey history. For the past several

years he has been employed by the prestigious Filson Historical Society in

Louisville, and he's also working on his own history of distilling in the

United States. From 1991 to 1996, Mike was the North American Archivist for

United Distillers International. We first met Mike shortly after that, in

his role of historian and archivist for the Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey

History in Bardstown, and we’ve spent many a happy (if sometimes blurry)

hour tossing historical ideas and theories back and forth while pouring fine

bourbon into each other’s faces. It was Mike who called us ( on about

three days notice) and invited us to attend this event as his guest.

Chris is an expert at explaining bourbon-making, a complicated mix of science

and art, and he uses this Similarities and Differences method to make our

full day of learning about bourbon whiskey very effective (he uses the same

techniques when he’s training industry professionals) and to hold the

interest of a small but intense group of bourbon enthusiasts for over seven

hours, in a way that would draw the envy of any preacher.. or college professor.

Oh, all right, it’s true that there are alcohol libations involved,

and secret wonders to behold, such as are rarely opened to mere mortals like

us. But in the hands of a lesser enlightener (a certain freshman U.S. Civics

& Government instructor comes to mind) even these wonderful props would

only make it easier to fall asleep.

Well, no one sleeps today.

And by the end of the day, not a single member of the group has not

asked a question or made a comment.

Whiskey

101

The event is being held at the beautiful

Labrot & Graham distillery,

just out of Versailles on McCracken Pike. We have visited the distillery

several times before, including a

similar

(but much shorter) event a couple years ago, hosted by Lincoln Henderson

and Wild Turkey’s Jimmy Russell. This one begins at 10:00 in the morning,

and we leave home in plenty of time to get there (Linda lied and told John

it would start at 9:30. "John time", she calls it). The weather has been

somewhat threatening, with talk of snow and ice to follow the storms we’ve

been having all week. But, other than a snow squall or two, it isn’t

bad at all, and we actually have sunshine and blue sky for much of the day.

Except for the distillery tour itself, we will be spending the entire day

in the conference center, a separate building, with a full kitchen, located

among the distillery buildings and designed for presentations, dinners, and

other social functions. This is where we ate dinner when we were here for

the Bourbon & Bluegrass event. It also contains Elijah Pepper, the most

social and human-friendly of the many distillery cats. Elijah makes it his

business to greet each of the guests before retiring to sleep in a sunbeam

coming through the window.

Chris begins with what he calls "Whiskey 101", a rather comprehensive look

at the basics of American whiskey. We will begin with where whiskey came

from and how it got to be the product we know today, and then we'll look

at the five elements that define and shape a particular style of whiskey.

What they all have in common, and what makes one unique from another.

Similarities,

The Origins of American

Whiskey

Chris explains that fermented beverages have existed in nearly every human

culture, as far back as our history goes. Mike reinforces that by pointing

out evidence that the making and trading of beers (fermented grain) and wines

(fermented fruit) can be found in the most ancient of ruins. Likewise, the

art of distilling has been known for thousands of years. But its introduction

into whiskey’s European culture came from the Islamic Moors who ruled

what would later become Spain. These Arabian descendants used the distillation

process in many fields, including industry and science, extracting the spirit

from fermented fruits (and perhaps grains as well) which they called "Al-Kuhl"

and which we call "alcohol".

Manufacture and trade of distilled beverages is not generally associated

with the Islamic Arabs and Berbers of Andalusia (Spain). Their interest in

alcohol is said to be mostly for its solvent value; alcohol was the primary

solvent for perfumes, cosmetics, and medicines. Of course, they could hardly

have failed to notice its important anesthetic qualities. However it wasn’t

until after Charlemagne’s conquest that we begin to see fermented beverages

undergoing distillation by French monks to obtain the ardent spirit for brandy

and liqueurs. Interestingly, the French called this spirit, "Eau de Vie",

literally "Water of Life". And that’s the simple mistake. The French

term is a direct translation of the Latin "Aqua Vitae", which also means

"Water of Life", but it appears that’s not what the distilled spirit

was originally called. The French monks’ use of the Latin term came

from the common Spanish name for alcohol, "Acqua de Vitae" which means, not

"Water of Life", but "Water of the Vine" (or "Grape Liquor"). A little more

mundane than the esoteric alchemists’ word for the fundamental elixir

of life, perhaps, but it does indicate that distilled brandy from the vineyards

of Jerez may have been enjoyed in Islamic Spain before reaching the Roman

Catholic valleys of Cognac.

Charlemagne and the French monks were familiar with the monks from Ireland

who worked closely with them to establish Christian order as the Moors were

driven out of Spain. It is very likely that the art of distilling fermented

products was brought to the barley beer makers of Ireland at that time. And

that’s how the (mistranslated) "Water of Life" phrase came to be applied

to grain distillate in the islands of the Erse, where it became "Uisgae-Beatha"

, and later in the lands of the Celts, Welks, and Angles, where it was known

as "Uisquebaugh".

And it’s from these terms that we get the modern word "Whiskey".

Or is it Whisky? Chris points out that the Irish distillers always spell

it with an "e". The Scots always spell it without the "e". Canadians spell

it "whisky", and Americans spell it "whiskey". That is, except when we

don’t. Which is often. Chris’ company, Brown-Forman spells it "whiskey"

on the Woodford Reserve bottle, but "whisky" on both Old Forester and Early

Times. Their Tennessee product, Jack Daniel’s is Whiskey, but the only

other existing Tennessee whiskey, George Dickel is Whisky. So is Maker’s

Mark. According to Chris there is no official "correct" spelling, despite

the heated discussions that are sometimes held on this subject in taverns

and pubs on both sides of the pond. And in Japan. And in Sweden. And Australia.

And everywhere.

While working up this web page, John has discovered that Chris isn’t

100% right about that, and the whole truth turns out to be even funnier than

you’d imagine… According to

Charles Shields the officially

defined spelling of whisky in Scotland included the "e" until the early twentieth

century. And upon looking up Title 27 Chap.1 Part

5 of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, which is the legal

definition of all distilled beverages made or sold in the United States,

we find that it spells the word "whiskey"…. But only once, on page 55.

It uses "whisky" (without the "e") exactly one hundred and eighty seven times.

Well, I guess that should put an end to that question once and for all, huh?

Chris also touches on the history of whiskey in America, bringing up the

Whiskey Rebellion and George Washington, which Mike Veach will show us in

more detail during his presentation.

The Five Sources of Whiskey

Flavor

In the second part of our Whiskey 101 session, Chris introduces us to the

five factors that determine the nature of a particular whiskey.

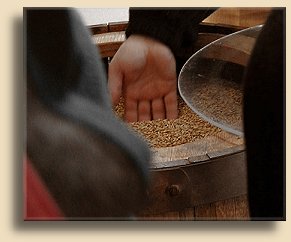

The GRAIN

In Ireland, the grain used is barley. Just barley, except that neutral spirits

are added to make blended Irish whiskey. And most Irish whiskey is blended.

The neutral spirits are distilled from wheat or maize (what we call corn

in America), but there is no distinctive flavor (that’s why they’re

called neutral spirits), so the only flavor element is the barley.

In Scotland, barley is also the only grain that contributes flavor. But the

flavor is different. Partly that’s because the Scots tend to malt all

the barley, while the Irish malt only a portion and let the enzymes convert

the rest of the starch. Malting is the process of dampening the grain and

allowing it to begin to sprout. Like when you set seeds out on a damp paper

towel to sprout before planting them in a seed tray. Except that with the

malted barley, the process is halted as soon as it starts. We’re not

trying to grow new barley; we’re just trying to get nice juicy,

enzyme-enriched material to ferment. So, in Scotland, they tend to malt all

the barley, and once it starts it has to be stopped very fast. That’s

done by building a fire under the grain and letting the low heat and smoke

kill the process. It also changes the flavor of the grain, and that’s

where one of Scotch’s most distinctive characteristics comes from.

Especially in the western islands, where the material they burn is peat,

a kind of half-seaweed that grows in bogs along the coast. In the United

States, most straight whiskey is made from a mixture of three grains. The

requirement is for one – usually either corn or rye – to make up

over half of the grain in the mix with the others adding flavor. Neither

of those grains malts well, so the third grain to be added is nearly always

malted barley. By law, bourbon must consist of at least 51% corn, but in

reality the percentages are always much higher; 70% - 78% is pretty common.

And altering the proportions of these grains even a little can have a profound

effect on the finished whiskey, as we will soon see. In addition to the type

and proportion of grain, other factors include how dry or moist the grain

is (dry is good; stale is not), where it is grown (corn is often local or

neighboring states; distillers must often search as far as Minnesota or Canada

for acceptable malted barley), and how it is ground (fists have flown over

the relative merits of hammer mills versus roller mills, for example).

Does the distilled spirit "care" about all this? Certainly it does, although

perhaps not as much as you might think. But the fermentation does,

and that’s a good example of how each of these five factors is dependent

upon one another. Read on...

The WATER

The FERMENTATION

And they multiply. Boy, do they ever multiply! A few gallons of hungry yeasts

introduced into a 12,000 gallon vat of mash can turn it into a rolling,

bubbling cauldron in just hours. Yeasts aren't warm-blooded -- the single-celled

creatures don't even have blood -- but the activity alone is enough to raise

the temperature of a fermenting vat enough to warrant cooling coils in some

cases. It looks even more active than it is, because the fermenting vat is

rolling with big bubbles as if it were boiling. It isn't. The bubbles are

carbon dioxide gas, one of the byproducts of this yeasty bacchanal. The other

byproduct is alcohol, which is why the distiller is doing all this in the

first place. In three to five days most of the sugars and nutrients the yeast

eat will be gone, and the level of alcohol will have reached about 8%, which

is too high for the yeast to live in. So they stop reproducing and die. You

can learn more in a distillery than just stuff about whiskey... here's a

very graphic demonstration of environmental pollution issues that reach far

beyond the mash tubs of Kentucky.

Eating and reproducing; that's about all there is to life as a yeast. That,

and fighting off other yeast colonies. There are thousands of yeast varieties

(strains) lurking about any given location, ready to descend upon a nice

rich environment. Most of them don't eat the exact same nutrients, which

means they leave a differently polluted environment, and that means the whiskey

distilled from that vat will have very different characteristics. More often

than not, whiskey made from such a mash will be unacceptable. The distiller's

goal is to have every mash produce the same, consistent finished product,

and that means carefully controlling the activities that go on in the fermenters.

One way the distiller maintains this control is by not letting nature decide

which of the thousands of yeast strains will become the dominant one. Every

distillery maintains it's own, carefully tended strain of yeast. Keeping

the company yeast healthy and fresh and ready to rock'n'roll is one of the

most important tasks the distiller does. Right from the start, a fairly large

dose of this yeast is introduced into the mash and allowed to gain a good,

solid foothold. By the time a wild strain discovers the new mash and begins

to move in (with their leather jackets and chopped motorcycles, no doubt)

the homeboys will have already had a chance to gain strength and fortitude,

and thus drive the intruders away. Or at least keep their numbers down. Some

of the most talented distillers encourage multiple yeast colonies for the

additional flavors they produce. Jack Daniel's uses four house yeasts for

just that purpose.

Yeast, and more importantly for the distiller, the type of environment they

leave behind, are strongly affected by the environment they start off in.

And that's at the micro level. Which is the main reason that small variances

in the nutrients in the grain, the proportion of one grain to another, the

chemicals in the water, and so forth can have such a profound effect. Consistency

is the most important goal of the distiller. If everything is consistent

from one batch to another, and something is wrong with one particular mash,

it's not difficult to discover what it is and how to correct it. But there

are a lot of variables, and altering one will affect some or all of the others.

The distiller has to juggle all these, and he only has a few days (sometimes

just a few hours) to do it.

Other important factors that make up the fermentation environment include

the temperature at which each ingredient is added and how long it’s

maintained at that temperature, the size and even the shape of the fermenting

tank, and whether it’s made out of steel, copper, redwood, or cypress,

the temperature at which the yeast is added, what yeast is used and how is

it propagated and maintained, how big a slug of it is added to the fermentation

tanks, and whether that’s all at once or in stages, is there only one

yeast or several, and dozens of other variables. Including the composition

of the water. And the real trick for the master distiller is to keep each

"Tank of a Thousand Variables" as close to identical with all the others

(past and present) as possible. That guy you remember seeing on Ed Sullivan

spinning the plates on the poles had it easy by comparison.

The DISTILLATION

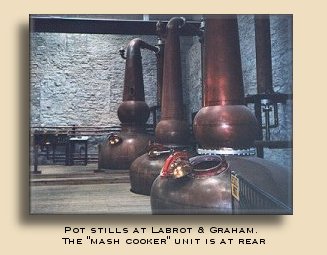

At Labrot & Graham, Brown-Forman wanted to revive the old methods of

using copper pot stills, but they needed a way to include cooking the mash

in the copper still as part of the process. They could have simply strained

off the liquid and distilled that (there are no legal requirements to include

the solids), but that would have altered the flavor and made the resulting

whiskey something that wasn’t "bourbon". On the other hand, pouring

bourbon mash into a pot still would ruin the whiskey, and probably the still,

too. What they did to resolve that dilemma was to have a third pot built,

larger and slightly different than the other two. This really isn’t

a still, in the normal sense of the word, since the proof is about the same

leaving it as it is going in. Chris characterizes this apparatus as a sort

of centrifugal cooker. The mash, with solids, is blown into the pot and against

the hot inner wall, where it circulates, cooking the grain solids and allowing

the liquid to drain out. The liquid is directed to the second pot, which

is the first actual still, along with the steam rising from the cooking mash.

So what goes into that still is really liquid wash, the same as it would

be in a Scotch or Irish distillery, along with the condensed steam laden

with flavors obtained from the cooked mash which are unique to bourbon.

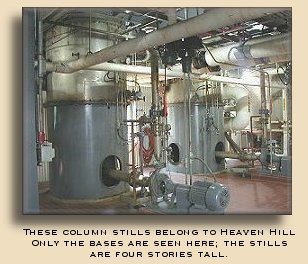

Everything in the process at Labrot & Graham is copper. Some of

the four-story tall column stills used at the other distilleries are all-copper,

too. Others are stainless steel, but even those contain copper elements. We’ve

heard stories that distillers put copper tubing, plumbing parts, and even scrap

copper into the steel stills to provide copper surfaces for the whiskey vapor to

contact, as a means of adjusting the flavor.

In an Malt Advocate Magazine article about copper stills, Lew

Bryson interviewed Chris, and also Lincoln Henderson. They pointed out that the

copper's function is mainly in reducing the effects of sulfur. Sulfur is a

natural component of the grain itself, and can also come from bacterial

infection during fermentation.

When the mash is distilled, these sulfur compounds wind up in the

spirit. The copper in the still causes the sulfur to combine with the copper and

form copper sulfate. Aside from the copper sulfate there are other oils and fats

from the grains and these combine with the copper sulfate as well to form a

black compound. Lincoln Henderson noted that this black compound is quite heavy

and greasy, especially at Woodford Reserve, because of the corn used for making

bourbon. Corn (maize, actually) is abundant in corn oil. Chris Morris calls this

corn oil-copper compound Grunge and it is responsible for the distinct heavy

copper smell and taste in the product. It is also difficult to remove from your

skin. According to Chris Morris the grunge starts at the top of the gooseneck,

the lyne arm and all the way through the condensation structure. Apparently this

effect works the other way in copper mining, in this case fats and oils are

introduced into a solution heavy in copper to extract the copper from the base

solution.

Chris explains that the Grunge is actually a polymer called ethyl

carbonate and the copper essentially cleans this out of the spirit. Most

food-grade equipment is made from stainless steel, and when the distillery

business was starting over from scratch after the repeal of national prohibition

a lot of distilleries started to utilize stainless steel stills. When this

occurred they noticed immediately the difference between copper and stainless

steel stills. In his article, Bryson points out that Seagrams did extensive

research to figure out what was going on. Chris notes that at Jack Daniels 100%

copper column stills are used, while at Old Forrester a hybrid stainless and

copper still is used. In the hybrid still all the internal infrastructure of the

still is copper. Lincoln interjects that they also throw a lot of copper pieces

into the top of the still, basically just a bunch of short sections of copper

tubing, which lasts until it disintegrates. The scrap tubing that they put into

the still at Brown and Foreman last about 3 years and when it is eventually

removed it is very brittle, about the thickness of paper and will crumble in

your hands.

So is what part of the distillate you elect to keep. Although most of what

vaporizes from the mash is ethyl alcohol (ethanol), there are dozens of other

alcohols that will evaporate below the boiling point of water. These include

all the elements that give new whiskey its flavor (since ethanol has no flavor).

They also include such lovely ingredients as propanol, methanol, and benzine.

Some of these unwanted distillates vaporize at lower temperatures than ethyl

alcohol and others at higher temperatures.

By law, whiskey must be distilled at no higher than 160 proof (80% ABV).

This is a quality assurance measure. Remember that ethyl alcohol has no flavor.

The flavor in distilled spirit comes from other chemicals that vaporize with

the alcohol. These are call congeners. Alcohol distilled at lower proof has

more impurities (in the form of these congeners) than high proof alcohol,

and most fine bourbon is distilled considerably below this proof. 160 proof

is generally thought to be the highest you can go and still maintain an

acceptable level of whiskey flavor. There is no lower limit, but economics

suggests that the level be kept fairly high. Besides, at lower proof levels

it becomes tricky (i.e., expensive) to stay within the limits that prevent

really bad flavors from being included.

One thing to consider is that, all other things being kept equal, whiskey

distilled at a lower proof will carry more of the grain and fermentation

elements into the barrel, and the lower alcohol level will tend to extract

less of the flavors available in the oak barrel itself. So the flavor of

the grain will make up a larger portion of that whiskey’s total flavor

than will flavors from the wood.

Of course, that’s if all other things really are equal. Such as…

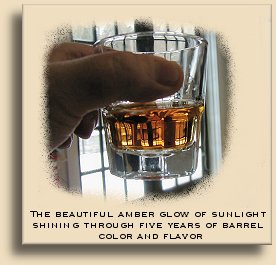

The MATURATION

And American White Oak is tough. Remember that most of these barrels can

only be used once and must then be sold to someone else. Barrels that don’t

hold up won’t bring a good price. And, unlike wine barrels, whiskey

barrels tend to be moved and rolled around a lot. Wine likes to sleep in

its casks, with as little movement and variation in temperature as possible.

Whiskey’s maturation process is active. It wants to expand into the

wood during the hot summer days and be sucked back out as it contracts during

the cold winters. In some distilleries, it wants to be stored in the

135º/summer, 20º/winter upper floors of the warehouse a couple

years, then be brought down to the constant 55º lower middle floors

for the next year or two. Some distillers (Brown-Forman is one) use heating

and cooling systems to create climate variations in the warehouse as needed,

without regard to the calendar year. And just how many years, or how many

cycles, makes a big difference in the character of the finished product.

As does the type of warehouse it’s maturing in. A low one or two-story

warehouse made of brick or stone?

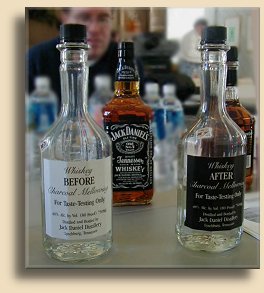

In the case of Tennessee whiskey, such as Jack Daniel’s, there is

another step to the

maturation process that isn’t present in any other type. Nearly

all whiskey is run through a charcoal filter before bottling, but Tennessee

whiskey goes through a long process of charcoal "mellowing" as soon as it

leaves the still and before being placed into the barrel. The whiskey is

dripped slowly through a ten-foot vat of sugar maple charcoal pieces, which

remove some of the harsh-tasting elements and cause the whiskey to be smoother

in mouth-feel. It is this mellowed whiskey that is then aged in the new charred

oak barrels. The process takes over a week to complete and Chris points out

that it is not filtration, the way a charcoal filter would be. While the

activated charcoal in a filter is measured in microns, the chunks of charcoal

in the mellowing vat are about the size of a fingernail. They don’t

really remove anything, but they do react with the elements in the whiskey

in a beneficial way. The resulting flavor is altered, however, and that’s

the chief distinction between Tennessee Whiskey and Bourbon.

Chris says that all the other factors – Grain, Water, Fermentation,

and Distillation – account for only about 40% of the final character

of the whiskey.

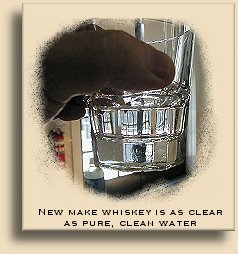

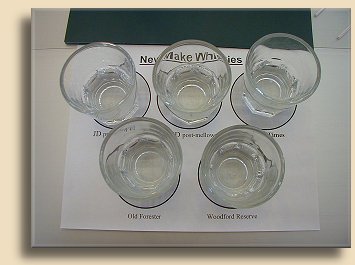

New Make Whiskey -

Similarities,

and Differences

And that completes Whiskey 101, Chris’ introduction and background.

Now it’s time to see just what sort of differences all these variables

(or at least some of them) can make. To do this, Chris has brought along

some examples for us to use. This morning we will be learning to recognize

the similarities and differences among whiskeys that have had no influence

at all from maturation. These are not what you’d buy in the store. Indeed,

outside of training and educational events such as this one you can’t

obtain these whiskeys at all. These are "new make", essentially

raw-from-the-still "white dog" which has been reduced to a tame 80 proof

for the purpose of comparison. Chris points out that in the day-to-day world

of testing and tracking whiskey, the tasters often work with new make at

only 40 proof. Tasters also usually don’t swallow the samples they’re

tasting, but our session will be more enjoyable if less accurate.

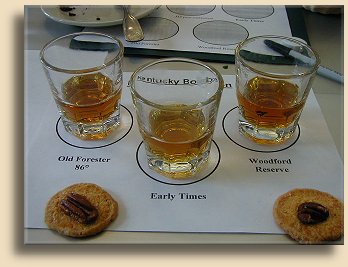

In front of each of us is a paper placemat printed with positions for Early

Times, Old Forester, Jack Daniel’s Pre-Mellowing, Jack Daniel’s

Post-Mellowing, and Woodford Reserve. There is a glass at each position.

Chris passes the bottles among us and we can pour as much as we like into

our glasses. About an ounce or so seems appropriate. Once the glasses are

all poured, Chris begins by introducing us to two whiskeys that are very

closely related, yet quite different from one another…

Early Times and Old

Forester

There is a trend among the distillers of premium whiskeys (especially single

malt scotch) to brag about not being chill-filtered. And some bourbon distillers

(or at least the marketing departments) are beginning to jump on that bandwagon,

too. But if you think about it, that position doesn’t make much sense

when applied to fine bourbon. At the legal minimum (for bourbon) of 80 proof

a lot of flavorful material must be removed to prevent the haze. But as the

percentage of alcohol increases, the tendency toward cloudiness decreases

dramatically. So the amount that must be filtered out becomes less. As the

alcohol level crosses over 100 proof (50%), whiskey reaches a point where

it isn’t prone to develop a haze at all. Most fine single-malt scotch

is bottled at between 80 and 90 proof; only a few reach above 50% alcohol.

But nearly all of the finest bourbon is at least 100 proof, and sometimes

far above that.

Although we didn’t do this today, Linda and I have tried an experiment

that nicely illustrates the subject of chill-filtration. To do this experiment,

you need only obtain a bottle of 80 proof bourbon and another of higher proof

(at least 100; more is better). Now simply pour a glass of each and add as

much clean, pure water to the higher proof drink as is needed to bring it

to about the same level as the 80 proof. Only a few drops should be needed.

You’ll quickly see just how much of the flavor was lost in bottling

the heavily-filtered lower proof version.

But Chris doesn’t include these whiskeys to show us the effects of

chill-haze. That’s just a little added bonus, brought to us by Mother

Nature (in the form of sub-freezing temperatures well below the average in

this part of Kentucky, even for January). What Chris wants to illustrate

for us here are the similarities and differences in bourbon whiskeys when

the maturation factor is not present. To do this, he is presenting two examples,

both produced at Brown-Forman’s Early Times distillery in Shively. One

is whiskey that would have eventually become Old Forester bourbon, the other

would have become Early Times.

Technically, neither of these products could be sold as "bourbon", or even

"whiskey", since neither has ever touched the inside of a new charred oak

barrel (or any other kind), but they make a fine pair of educational devices.

Chris has us start by "nosing" the Early Times. This whiskey is made to be

simple, straightforward, and inexpensive. The finished, aged product is intended

to satisfy drinkers who want a smooth, mild-flavored whiskey to enjoy in

a mixed drink. Chris invites us to share our impressions of the odor and

aroma, and everyone quickly agreed that the smell of corn is very present.

Later, when we actually drink and taste it, the uncomplicated taste of the

corn is especially pronounced. If you’ve ever tasted "Georgia Moon"

(the commercial product that’s sold in Mason jars, not the home-made

variety also often served that way) you’ll have a good idea of the flavor.

That’s an unaged, raw white 80 proof whiskey, too, but it’s pure

corn whiskey. Early Times uses a classic bourbon formula, but there’s

a high proportion of corn in the mix and the flavors of the other grains

are not emphasized.

Then we try our sample of the Old Forester product. Now, in real time we

actually do all the nosing of all the new make whiskeys first, then go back

and do the tasting. And it’s all there at once and we can skip about

and go back and forth as we choose. But it makes more sense to write it this

way, to show what we’re learning about the similarities and differences.

Chris teaches almost as much in an aside or by answering a question about

something we’re not even covering as during the "planned" part of the

seminar, so what you see here is, itself, only a "taste". You really have

to be there to get the full impact.

Old Forester is Brown-Forman’s flagship brand. It is the brand that

George Garvin Brown founded the company on and the brand that CEO Owsley

Brown II offers with pride today. Made in the same distillery as Early Times,

made by the same distillers, using the same corn, rye, and malted barley

(but in different proportions), fermented in the same tanks, it will take

a very different path through the maturing phase and become a very different

whiskey. We’ll see that this afternoon as we explore these whiskeys

in their fully-aged and ready-for-consumption condition. In fact, in the

United States market, only Old Forester will even be bourbon.

But at this point in their young lives, these two brothers are much more

closely related. Still, the differences are anything but subtle. Like the

Early Times (and common to any bourbon) there is corn in the aroma and the

flavor. But in Old Forester the corn isn’t as dominant. The overall

flavor is much spicier and fruitier. And balanced. Where the Early Times

whiskey seems to grab the sides of your tongue, the Old Forester flavors

touch all around your mouth, ending in the middle of the top of your tongue.

Tasting the two side by side really makes that clear. And this demonstration

really illustrates what Chris has told us about the effects of fermenting

and distillation on bourbon. For example, a different strain of yeast is

used for each, and the length of time they ferment is also not the same.

Early Times uses a yeast strain they call 1A and ferments for three days,

while Old Forester uses a strain called 1B and ferments for five days. Chris

said they tried fermenting it for only three days and it tasted terrible.

Later, when we add the premium Woodford Reserve to our repertoire, there

will be a new dimension to be learned, as we become aware of how a completely

different type of distilling process (distilling mash in the Labrot &

Graham copper pot stills) affects what is essentially the same grain formula,

yeast, and fermenting style as Old Forester.

We’ve visited many distilleries, and we’ve sampled many, many different

aged bourbons. We’ve also sampled our share of white dog and similarly

unaged whiskey. But this is the only time we’ve had the opportunity

to compare and learn so much about bourbon in its infancy. And oh, what a

fascinating infant it is!

Jack Daniel's Tennessee

Whiskey

What disqualifies Jack Daniel’s as a bourbon is the extra process of

charcoal mellowing we mentioned earlier. That’s also the whiskey’s

claim to fame and one of the reasons for it’s being the most popular

American whiskey in the world. The reason it's unacceptable is that the mellowing

step (it’s also called "leaching", but not by the company) imparts a

flavor (maple smoke?) to the whiskey, and that's not allowed under the

specifications for bourbon.

Okay, so now we are looking down into two crystal clear glasses of unaged

Jack Daniel’s whiskey. One is just as it comes from the still (except

diluted to 80 proof). The other is the same product after it has been run

through 10 feet of the Lincoln County Process and become Tennessee Whiskey

(and reduced to the same 80 proof). Other than that they’re identical,

so what we have here is a close up examination of just how much a difference

this process can really

make.

We smell the first sample. Or at least we think we do. There is hardly any

distinctive aroma, not at all like either of the bourbon products. Not even

a corn smell stands out. The post-mellowing sample has acquired a slight

(noticeable but not strong, and really quite pleasant) smoky aroma. When

we taste the samples the differences are much more evident. The un-processed

sample is rather harsh, while the taste of the mellowed whiskey is remarkably

smooth and balanced, considering that this is unaged whiskey. John notes

that, in the days when the customer brought his jug and filled it with clear,

white whiskey directly from the still, a distillery that offered the mellowed

product would be worth traveling all the way to Lynchburg for, and that was

probably the basis for much of Jack Daniel’s early success. Of course,

the smoky, slightly burnt taste (Mike calls it phenol) is very much present,

even more so than it would be in the aged product. But if you’re a fan

of Jack Daniel’s and you appreciate that particular flavor you’d

really love the mellowed but unaged sample we’re trying. By the way,

Chris mentions that they use four different yeasts to ferment the mash for

Jack Daniel’s whiskey.

Oh, and also by the way, Reagor Motlow – proprietor of Jack Daniel’s

in 1943 when the "not a bourbon" decision was handed down – might be

a good candidate for the "Spin Doctor of the 20th Century" award. From the

moment the letter of notification was received, Motlow began a very successful

campaign, carried on by Brown-Forman after they purchased Jack Daniel’s

in the 1960’s, to educate people to appreciate that the U. S. Government

had established the special category of "Tennessee Whiskey", that was distinct

from Bourbon. The fact is, however, that the letter doesn’t say that

at all. It only says that Jack Daniel’s cannot be labeled "Bourbon"

and suggests that it may still be called "whiskey". The Bureau of Alcohol,

Tobacco, and Firearms official definitions of whiskey (and all spirits) makes

no reference at all to Tennessee Whiskey. In other words, the category (like

their position as Distillery No. 1) exists only in the Jack Daniel’s

marketing department.

John says that there is a sixth source of whiskey flavor that Chris didn't

mention. Some (maybe more than some) of the more idealistic enthusiasts will

shudder at the mere mention of this, but John believes that

The

ATTITUDE of the whiskey should be added to

the list. And Jack Daniel's just may have more attitude than all the other

brands together. The way John puts it is this: if you REALLY want PURITY,

then drink vodka. Everything wonderful about whiskey is the result of impurities.

Specifically, the art with which the distiller manipulates those impurities

to produce a delicious and enjoyable product. And to tell the truth, the

"truth" itself might be one of those impurities. We learned that the shape

of the still can affect the final product; but doesn't the shape of the bottle

have just as profound an effect on the drinker? You might disagree, but the

folks who designed Woodford Reserve's beautiful flask surely think so. Is

whiskey that is brilliantly clear and dark more desirable than whiskey that

is thin-looking and cloudy? Does Jack Daniel's taste better, "knowing" that

it's a special kind of whiskey? Or that it's "the first registered distillery"?

Or that the distillery employees like to sit around in the afternoon and

whittle? Or that Frank Sinatra loved Jack Daniel's so much that he ordered

a bottle to be buried in his coffin with him? Well, yes it certainly does.

Millions of Jack Daniel's drinkers (and the Brown-Forman marketing staff)

understand that. That ATTITUDE affects the flavor and quality (the human

kind, not necessarily the measurable kind) just as much as the grain, water,

fermentation, distillation, or maturation does.

We knew all that before we came the Academy today. What we DIDN'T know, because

the comparison isn't available to people except at events such as this, is

whether the highly-touted "charcoal mellowing" was real or just another nice

marketing idea. The answer is, it's real, all right. Very real. That mellowing

step has a profoundly beneficial effect on the whiskey. It would be interesting

(but probably not worth the cost) to barrel and age some Jack Daniel's without

the mellowing step, just to see what it would be like. From the taste of

the new make, it would seem that it wouldn't be very successful. The mellowing

step is a vital part of Jack Daniel's identity. Although we didn't cover

it very thoroughly (distillers never do, for some reason), all of the bourbon

that is distilled in those giant column stills goes through a second distillation

process afterward. The step is called "doubling" and it's a lot like a pot

still. Jack Daniel's doesn't have a doubling step. The mellowing process

takes the place of that step, and the result is quite different from bourbon

(or any other whiskey for that matter). It's funny, we came to a Kentucky

distillery, the pride of a Kentucky distilling company that also happens

to own a Tennessee whiskey distillery. And we learned quite a lot about Kentucky

bourbon, including Woodford Reserve. But one thing that we really

learned to appreciate today was the uniqueness of Jack Daniel's Tennessee

whiskey, and that it extends beyond the image.

Even if we do still like bourbon better

At this point we get the opportunity to enjoy a fine lunch prepared by Labrot

& Graham's excellent chef, David Larson. Two years ago, when we were

here for a dinner event, David presented four courses of gourmet-quality

cuisine, featuring dishes made with bourbon, and suitable for the finest

restaurants. Today he has set out an equally delightful lunch in a much more

down-home, almost picnic style. The main entrees are an oriental chicken

salad and barbecue sandwiches made with Woodford Reserve bourbon. The barbecue

is unusual, especially for this area, because the meat is beef rather than

pork. It's served sandwich-style on buns, in individual portions wrapped

with aluminum foil. The oriental chicken salad is served on a platter from

which we serve ourselves. Along with these are a big bowl of rich cole slaw

and basil potato salad. David has made chocolate cake with Woodford Reserve

bourbon for dessert. It's thick and rich and it goes soooo well with a glass

of bourbon. John and several others decide to hide a piece or two to enjoy

with the second tasting later this afternoon.

Elijah doesn’t join us for lunch, but as Linda walks past the kitchen

she sees that they’re preparing a special plate just for him. Life sure

is rough when you’re a distillery cat.

BEHIND-THE-SCENES TOUR -- Part

1

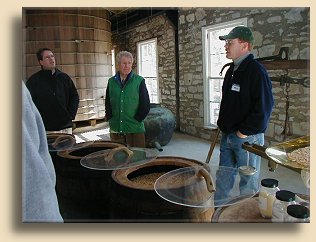

Chris now takes us on a tour of the Labrot & Graham distillery. Besides

being awesomely beautiful and meticulously restored, this site really is

one of the oldest commercial distilleries in Kentucky. Long before 1878 when

Leo Labrot and Jim Graham bought it, the distillery was operated by the Pepper

family (our favorite distillery cat is named after the founder, Elijah Pepper).

It was second-generation owner Oscar Pepper who hired an out-of-work immigrant

Scottish chemist, James Crow, to be his distiller. Crow brought a background

of scientific training to an industry that had survived pretty much on luck

up to that point. More importantly, as Chris pointed out to us this morning,

Crow brought the idea of documenting everything that was done and the discipline

to duplicate successful processes to the smallest detail. While folklorists

like to tell of Reverend Elijah Craig inventing bourbon as we know it, it

is James Crow to whom historians usually bestow the honor of Father of the

Kentucky Bourbon Industry. And it was at this very site where he did all

that. As we look across Glenn Creek, we're looking at the same hillside he

looked at. In fact, that old abandoned ruin of a house on the crest of that

hill used to be Oscar Pepper's. Dr. Crow probably visited there many times

himself.

Although we cover most of the same things shown on the public tour, there

is a closeness and personalized presentation that is unique to this event.

We cover the grains and how they’re processed, the way the grains are

mashed and fermented. See our page about

our

other visits to this wonderful distillery, and you can also take

Labrot & Graham’s distillery

tour at their website. And we strongly recommend you take Chris Morris’

own tour of the Early

Times distillery, as well.

Returning to the Conference Center, our next event is a slide show presentation

given by Mike…

HISTORY of BOURBON

WHISKEY

In the United States, corn is a very common grain from which to make whiskey,

but it wasn’t always so. The original American whiskey industry was

built on rye. Barley doesn’t grow all that well in the part of the U.S.

where the original colonists lived, and most of the original whiskey makers

weren’t barley-growing Scots or Irish anyway, they were German and Swiss

Lutherans and Mennonites who, along with the more conservative Amish, became

known as the Pennsylvania Deutsch. The grain they grew was the grain their

families had always grown in Europe, rye, and it was from that grain that

the American whiskey industry was born.

On the other side of the Appalachian mountains, in the western frontier valleys

of Virginia that would later become the commonwealth of Kentucky, folks were

settling on homesteads provided by the new federal government. If you would

agree to clear an area, build a home, and raise corn, you could get forty

acres of wilderness land for your own. This was very attractive, and many

people made use of Daniel Boone’s wilderness trail to settle in the

new frontier. They cleared the forest; they built their log cabins; they

tilled the newly-cleared soil and planted corn. And they were joined by a

small flood of people coming down the Ohio river from western Pennsylvania

after the Whiskey Rebellion who

would also now be growing corn.

Mike points out that neither the taxation on whiskey, nor the resistance

to paying it, were limited to western Pennsylvania. The exact same laws and

circumstances applied to Kentucky as well. But there were two very important

differences that caused the resistance in this area to be, well, covered

up.

In 1800 Spain sold the Louisiana Territory west of the Mississippi back to

France, and three years later France sold it to the United States. Trade

with New Orleans became profitable, and that included trade in distilled

spirits. John and Mike have long discussed the possibility that it was this

market of newly prosperous people of French descent and with French tastes

to which was directed a type of spirit, made from whiskey and aged (as is

cognac) in charred oak barrels to give it a sweetness and red/brown color.

To make it even more attractive, the spirit may have been given a name that

evoked French Royalty, in much the same way that there is Napoleon brandy.

Perhaps this new spirit was called "Bourbon". It’s a non-standard theory

and one that Mike is researching, and John feels excited that Mike has spoken

about it as part of this presentation.

BEHIND-THE-SCENES TOUR -- Part

2

At the conclusion of Mike’s hour, we get to take another tour. This

time we are shown the warehouse and the bottling plant. If you’ve taken

the Labrot & Graham online tour you’ve already seen this, and you

can also see it on our page about the distillery. So we won’t spend

much time here, except to say that Chris continues to tie everything we see

to the points he taught us about warehousing, barrels, and maturation. And

as we look at the tiny bottling line (L&G is the smallest commercial

bourbon distillery in existence) we get the opportunity to sample some Woodford

Reserve Distillers’ Select at true barrel strength (about 110 proof).

AMERICAN WHISKEY - Similarities and Differences

Back at the conference center, we again find before us a placemat marked

with the names of whiskeys and clean, empty glasses placed upon them. And

again, Chris passes bottles around for us to pour from. This time the whiskeys

are the fully aged commercial product, just as you would find it at your

favorite liquor source. And again, Chris will guide us into comparing one

to another to illustrate the similarities and

differences.

STYLES OF AMERICAN WHISKEY -- Tasting

the Finished Product

Early Times, Old Forester,

and Woodford Reserve

The Early Times we tried this morning was "new make", and could have become

either a Straight Bourbon (if aged in new charred oak barrels) or a Kentucky

Whiskey, which is what we’re sampling now. We smell and taste the simplicity

of the whiskey, and how the

Along with the chocolate cake some of us had squirreled away for this occasion

at lunchtime, we are now also tempted with Chef Larson's top-secret recipe

(meaning Marnie wouldn't tell John when he asked her) Shaker Wafers. Shown

here with glasses of aged bourbon, they are sweet and salty and cheesy and

nutty... and addictive enough to deserve a spot on the controlled substances

list.

We are tasting three different offerings from Jack Daniel’s. The Black

Label Old No. 7 Brand known and loved around the world, a Single Barrel to

compete in the ultra-premium market, and Gentleman Jack, an offering appealing

to more subtle tastes. As we sample the No. 7 Brand, Chris tells us that

what’s in the bottle is a mixture of barrels from various parts of the

warehouses, chosen to maintain a consistent flavor and color profile, and

about five years old. The single barrel is the same whiskey, but is seven

or eight years old and those barrels are all from the area of the warehouse

called the Buzzard’s Roost – that is, way up at the top where the

temperature variation is the greatest. Gentleman Jack is made from a slightly

different (and secret) recipe. It is slightly younger, about 4 ½ years

old, which might seem to make it a little harsher. But it is run through

a second charcoal mellowing process after being dumped from the barrel and

before bottling, and that makes it even mellower and smoother. In fact, it

seems as if the only flavor detectable is the slight smoky taste that’s

characteristic of Jack Daniel’s.

WOODFORD RESERVE BOURBON ACADEMY

Thanks, Chris and Mike. Thanks, Marnie and the staff at Labrot & Graham

Distillery. You really made our year. We’ve learned a lot today (and

even more later as we review and check our notes for making this web page)

and that’s always a lot of fun. And thanks to Brown-Forman. Every single

whiskey we sampled today is a Brown-Forman product. We can't think of any

other single bourbon company with enough range in their product line to be

able to offer such a comprehensive look into this wonderful beverage.

Skåol!

January 18,

2003 -- The Woodford Reserve

Bourbon

Academy

Labrot

& Graham

Distillery --

Versailles,

Kentucky

It's a bourbon-lover's dream. In fact it's TWO bourbon-lovers'

dream...

We spend an entire day learning to appreciate bourbon with Chris

Morris

The fact is, people from around the world

are fascinated with what goes on in the background for only a few things

and the production of alcoholic beverages, from beer and wine to distilled

spirits, rank pretty high on that list (which may, indeed, include mayonnaise

as well).

The fact is, people from around the world

are fascinated with what goes on in the background for only a few things

and the production of alcoholic beverages, from beer and wine to distilled

spirits, rank pretty high on that list (which may, indeed, include mayonnaise

as well).

We are teased.

We are amazed.

We learn things we didn’t even know we didn’t

know.

and Differences....

Chris

moves directly from here to Scotland and Ireland and the Celtic word

"Uisquebaugh", from which we derive the modern word "Whiskey" (or "Whisky";

more on that later). But there is a little more to the story (isn’t

there always?) and it’s kind of amusing how different cultures can see

the progress of history from different directions. Because, you see, although

the Irish word "Uisgae-Beatha", meaning "Water of Life", may date from as

far back as the sixth century (900 years before the earliest records in

Scotland), there is reason to suspect that whiskey’s origins date back

even further, into the grape vineyards of the Iberian peninsula. But it’s

not likely that the Irish monks learned about distilling from the Spanish

Muslims.

Chris

moves directly from here to Scotland and Ireland and the Celtic word

"Uisquebaugh", from which we derive the modern word "Whiskey" (or "Whisky";

more on that later). But there is a little more to the story (isn’t

there always?) and it’s kind of amusing how different cultures can see

the progress of history from different directions. Because, you see, although

the Irish word "Uisgae-Beatha", meaning "Water of Life", may date from as

far back as the sixth century (900 years before the earliest records in

Scotland), there is reason to suspect that whiskey’s origins date back

even further, into the grape vineyards of the Iberian peninsula. But it’s

not likely that the Irish monks learned about distilling from the Spanish

Muslims.

Their

very use of the term "Water of Life" tells us where the origins probably

were, and that’s because of a simple mistake…

Their

very use of the term "Water of Life" tells us where the origins probably

were, and that’s because of a simple mistake…

These

five Sources of Whiskey Flavor are the foundation, floor, framework, siding,

and roof of the whiskey – they determine its very character and soul.

One by one, Chris examines each with us, showing the various choices and

how each affects the final product. What follows here is only a brief outline.

These

five Sources of Whiskey Flavor are the foundation, floor, framework, siding,

and roof of the whiskey – they determine its very character and soul.

One by one, Chris examines each with us, showing the various choices and

how each affects the final product. What follows here is only a brief outline.

All whiskey is made from grain. That’s the similarity that all whiskey

has in common. It’s also what distinguishes whiskey from rum (vegetable

sugar - especially cane syrup), brandy (fruit sugar - grapes, peaches, and

so forth), and tequila (also vegetable sugar - but from the agave plant).

There is no sugar (or at least not much) in grain, only starch.

But

malting the grain (or at least some of it) produces enzymes that convert

the starch into sugar and that’s what is fermented.

But

malting the grain (or at least some of it) produces enzymes that convert

the starch into sugar and that’s what is fermented.

Take water for example. On one of our earliest visits to Bardstown, we stopped

for lunch at a restaurant with the sort of easy-going, relaxed service that

we’ve later come to appreciate, and while waiting for our ice tea we

did something we rarely do… we drank the water. Linda’s reaction

was, "This is the best water I’ve ever tasted. If the water where we

live tasted this good I’d drink it all the time!" The full meaning of

that took a minute to sink in before a light went on in John’s mind

and he responded, "Of course it’s the best water we’ve ever tasted.

Look where we are! That’s why it makes the best whiskey!" So now we

drink bottled water, purified and then with magnesium and calcium added back

in to create a delicious flavor. And, looking back on it, the odds are

that’s what the restaurant was using, too. Bardstown city water, like

all city water in the United States today, is treated for public safety and

probably tastes the same as Butler county Ohio water. And that wonderful

limestone that tastes so good and makes such good bourbon does really awful

things to the plumbing over time. These days, nearly all distilleries process

the water that they use. They do so with intent and with a great deal of

care, because the choices they make will strongly affect the flavor of their

final product. And not just because water is a major ingredient; actually

it’s not that major. Remember, only a little over 20% of the distillate

is water. True, when the whiskey is dumped from the barrel water will be

added to reduce the proof to the desired level, but that’s done with

totally characterless de-ionized water, not the calcium-rich limestone water

the distilleries talk so much about. No, the most important place where the

water affects the whiskey (and it’s very important, indeed) is in the

fermenting tanks…

… because it’s not really grain that ferments after all; it’s

not even grain starch converted to grain sugar. It’s grain soup. The

water is the chief ingredient in the mash that will be offered as a happy

breeding ground for the yeast. And it’s here, perhaps more than at any

other stage in the production of whiskey, that even the smallest of variances

can make big, big changes in the final product. Because the whiskey that

will be distilled is really not made from the grain itself, nor even from

a mixture of grain and water. It's made from distiller's beer, which in turn

is created by yeast colonies. Yeasts are micro-organisms that infest damp

grain (and other damp things) and live there. They feed on sugar and other

nutrients. They excrete carbon dioxide and alcohol.

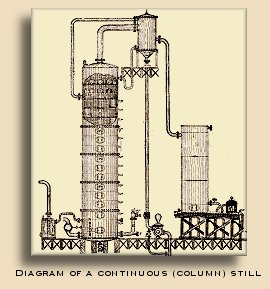

And then the fermented mash is pumped into the still. At least that’s

true of American whiskey. Scotch and Irish whiskies are made in copper pot

stills, as was bourbon at first. And only the liquid "wash" is sent to the

pot stills. One important way that bourbon differs from those whiskeys is

that it derives a significant part of its flavor from cooking the grain solids

in the mash during the distilling process. With the exception of Labrot &

Graham, all bourbon is distilled in the "continuous" or "column" still invented

in the mid 1800’s by Aeneas Coffey.

This apparatus was designed

to produce copious amounts of the pure, tasteless, industrial-quality alcohol

known as grain neutral spirit, and you wouldn’t expect it to be desirable

for making fine bourbon. In much the same way, the electric guitar was invented

to allow that rhythm instrument to be made loud enough to be heard in the

dance band, without regard to the distorted tone quality that resulted. And

in much the same way that B.B. King or Carlos Santana can make the electric

guitar sing exquisite and astounding music impossible to create on the finest

of C.F. Martin acoustic guitars, the master bourbon distillers of Kentucky

work those column stills to produce just the flavor profile they want for

their

product.

This apparatus was designed

to produce copious amounts of the pure, tasteless, industrial-quality alcohol

known as grain neutral spirit, and you wouldn’t expect it to be desirable

for making fine bourbon. In much the same way, the electric guitar was invented

to allow that rhythm instrument to be made loud enough to be heard in the

dance band, without regard to the distorted tone quality that resulted. And

in much the same way that B.B. King or Carlos Santana can make the electric

guitar sing exquisite and astounding music impossible to create on the finest

of C.F. Martin acoustic guitars, the master bourbon distillers of Kentucky

work those column stills to produce just the flavor profile they want for

their

product.

So the construction material is of vital importance to the distilling process.

The shape and size of the still is also an important factor.

Part

of the skill of the whiskeymaker is letting the vapors from the still bleed

off until the right temperature is reached before directing the flow into

the condenser, then diverting the flow again when the temperature has risen

high enough to pick up other foul elements. This is called handling the Heads

& Tails, sometimes known as the Foreshots & Feints.

Part

of the skill of the whiskeymaker is letting the vapors from the still bleed

off until the right temperature is reached before directing the flow into

the condenser, then diverting the flow again when the temperature has risen

high enough to pick up other foul elements. This is called handling the Heads

& Tails, sometimes known as the Foreshots & Feints.

If the otherwise identical whiskey

is distilled at higher proof, however, it will take less grain flavors into

the barrel and be capable of extracting larger amounts of tannin, sugars,

and vanilla, resulting in a finished whiskey very different in character

from the first example.

If the otherwise identical whiskey

is distilled at higher proof, however, it will take less grain flavors into

the barrel and be capable of extracting larger amounts of tannin, sugars,

and vanilla, resulting in a finished whiskey very different in character

from the first example.

… such as, just what kind of barrel are you going to put this whiskey

into, anyway? Well, it’s going to be made of oak. We know that, because

it’s the law, at least for American whiskey. And if you’re making

Bourbon, or Rye, or any other "straight" whiskey, it will be a new, charred

oak barrel. That’s the law; it can be any kind of oak. But in practice,

the only material used to make American whiskey barrels is American White

Oak. Partially that’s because white oak is the perfect wood for whiskey

barrels. It will stay watertight for many years. It will take a char

consistently, and it contains the right balance of tannins and sugars. And

also partially because there are only two barrel companies supplying all

the Kentucky and Tennessee whiskey distilleries, and they both use American

White Oak to make their barrels. Brown-Forman owns

Bluegrass Cooperage (the

other is Independent Stave

Co.), so they have complete control. Chris likes to say that they are

the only company that takes its product from the forest to the bottle.

An

eight-story high rack of barrels with a thin frame around it covered in sheets

of steel. On top of the hill? On the side? In a valley? Painted black? White?

Heaven Hill has warehouses scattered all over the place. Wild Turkey leases

warehouses in several counties, and you can bet that distiller Jimmy Russell

and his son Eddie know just what to expect from each location on each floor

of each one of them.

An

eight-story high rack of barrels with a thin frame around it covered in sheets

of steel. On top of the hill? On the side? In a valley? Painted black? White?

Heaven Hill has warehouses scattered all over the place. Wild Turkey leases

warehouses in several counties, and you can bet that distiller Jimmy Russell

and his son Eddie know just what to expect from each location on each floor

of each one of them.

The Maturation factor alone is 60% of the show.

The bottles containing both of these whiskeys showed the effects of cold

on non-chill-filtered whiskey. These samples have been reduced to 40% alcohol

(80 proof) and spending the night in the cold of Chris’ trunk has left

a noticeable cloudiness. Chris explained that the haze in caused by minute

traces of fat, proteins, and tannins that coalesce at very cold temperatures

to produce a milky look that some people find unattractive. Distillers insist

that the haze doesn’t indicate a quality problem, and will go away again

when the whiskey warms up to room temperature. The way this is normally prevented

is to chill the whiskey before bottling, run it through a fairly powerful

filter that will remove the haze particles, then bring the temperature back

up and bottle it.

Next

time it’s chilled (such as when pouring a glass over ice), there will

be no particles to produce a haze. The down side of doing this is that some

drinkers feel that a significant part of the whiskey’s flavor resides

in those elements that get filtered out.

Next

time it’s chilled (such as when pouring a glass over ice), there will

be no particles to produce a haze. The down side of doing this is that some

drinkers feel that a significant part of the whiskey’s flavor resides

in those elements that get filtered out.

As

part of it’s flavor profile, some of Early Times’ U.S. product

will be aged in used charred and new uncharred barrels, and will thus be

labeled "Kentucky Style Whiskey", not "Straight Bourbon Whiskey". Chris explains

that Old Forester is not exported overseas, so the role of Brown-Foreman’s

bourbon outside the country is filled by Early Times Straight Bourbon Whiskey

(aged only in new charred oak barrels).

As

part of it’s flavor profile, some of Early Times’ U.S. product

will be aged in used charred and new uncharred barrels, and will thus be

labeled "Kentucky Style Whiskey", not "Straight Bourbon Whiskey". Chris explains

that Old Forester is not exported overseas, so the role of Brown-Foreman’s

bourbon outside the country is filled by Early Times Straight Bourbon Whiskey

(aged only in new charred oak barrels).

Jack Daniel’s isn’t bourbon.

Jack Daniel’s isn’t bourbon.

Jack Daniel’s isn’t

bourbon.

![]()

Lunch

Lunch

Michael Veach – Filson Historical Society of Louisville

Chris

had introduced us to some of the history of American whiskey in Whiskey 101,

but Mike’s presentation is far more detailed. And besides, he has pictures!

In addition to telling us about whiskey history, Mike has brought along slides

with photographs from the Filson archives.

Chris

had introduced us to some of the history of American whiskey in Whiskey 101,

but Mike’s presentation is far more detailed. And besides, he has pictures!

In addition to telling us about whiskey history, Mike has brought along slides

with photographs from the Filson archives.

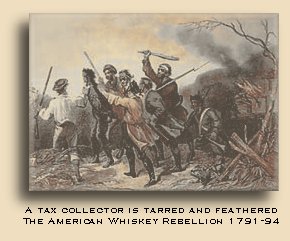

Ah

yes, the Whiskey Rebellion. Maybe Abraham Lincoln was wrong. Maybe it

didn’t take fourscore and seven years to test whether the new nation

could long endure. Maybe it didn’t even take seven years. Maybe it only

took a determination to show that the new federal government could bring

overwhelming force to bear in any dispute that questioned its authority.

And that’s what newly elected president George Washington did when the

whiskeymakers in western Pennsylvania declared that they would not pay the

taxes levied against them to support the Revolutionary War. Especially since

payment was not acceptable in the currency of their realm, whiskey, and had

to be paid using dollars borrowed from Alexander Hamilton’s bank. Some

would say, of course, that the tax was levied more for the purpose of destroying

a competing local monetary system than for liquor control purposes, but whatever

the motivation, the result was that President Washington sent an army equal

in size to what was used for the entire Revolutionary War to put down a rebellion

that consisted of a single burned home, some tarring and featherings, the

disruption of mail service, and a lot of angry threats. The rebellion broke

up as soon as the troops began marching and ended with a couple of arrests,

who were later pardoned despite never actually being charge with a crime.

However, the whole affair demonstrated the superiority of the federal government,

a lesson that lasted another fourscore years.

Ah

yes, the Whiskey Rebellion. Maybe Abraham Lincoln was wrong. Maybe it

didn’t take fourscore and seven years to test whether the new nation

could long endure. Maybe it didn’t even take seven years. Maybe it only

took a determination to show that the new federal government could bring

overwhelming force to bear in any dispute that questioned its authority.

And that’s what newly elected president George Washington did when the

whiskeymakers in western Pennsylvania declared that they would not pay the

taxes levied against them to support the Revolutionary War. Especially since

payment was not acceptable in the currency of their realm, whiskey, and had

to be paid using dollars borrowed from Alexander Hamilton’s bank. Some

would say, of course, that the tax was levied more for the purpose of destroying

a competing local monetary system than for liquor control purposes, but whatever

the motivation, the result was that President Washington sent an army equal

in size to what was used for the entire Revolutionary War to put down a rebellion

that consisted of a single burned home, some tarring and featherings, the

disruption of mail service, and a lot of angry threats. The rebellion broke

up as soon as the troops began marching and ended with a couple of arrests,

who were later pardoned despite never actually being charge with a crime.

However, the whole affair demonstrated the superiority of the federal government,

a lesson that lasted another fourscore years.

choice

of used or uncharred barrels keeps that simplicity from being overwhelmed

by barrel flavors. We compare it Old Forester, which almost seems to have

met it’s other half during the maturation process. The flavors added

by the tannins and sugars in the barrel have married with the complexity

that was in the new make whiskey to produce a classic bourbon. The Woodford

Reserve that we are sampling this afternoon is not the product of the copper

pot stills. It’s the current commercial product that was made at the

Early Times distillery but matured in the Labrot & Graham warehouses.

The differences in flavor between it and Old Forester are almost entirely

attributable to the differences in maturation, so this also makes a great

example of that factor’s contribution.

choice

of used or uncharred barrels keeps that simplicity from being overwhelmed

by barrel flavors. We compare it Old Forester, which almost seems to have

met it’s other half during the maturation process. The flavors added

by the tannins and sugars in the barrel have married with the complexity

that was in the new make whiskey to produce a classic bourbon. The Woodford

Reserve that we are sampling this afternoon is not the product of the copper

pot stills. It’s the current commercial product that was made at the

Early Times distillery but matured in the Labrot & Graham warehouses.

The differences in flavor between it and Old Forester are almost entirely

attributable to the differences in maturation, so this also makes a great

example of that factor’s contribution.

Jack Daniel's -- a Jack for All

Trades

Jack Daniel's -- a Jack for All

Trades

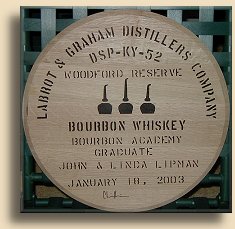

COMMENCEMENT CEREMONIES

Well,

it is now nearly 5:00 and we’ve spent almost seven hours intensely studying

the intricacies of this wonderful beverage. John is wondering, "Do people

who enjoy Jelly-Bellys or Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream do this sort of

thing?" Chris is wrapping everything up and getting ready for the award

presentations. Did we mention award presentations? Oh yes, as we arrived

and signed in this morning, Labrot & Graham’s lovely social director

Marnie Walters asked us to include how we’d like the course completion

award to be titled. We were expecting a diploma. We were wrong. Delightfully

wrong. As the day ends, Chris and Marnie bring out the awards and distribute

them. Each is an actual Labrot & Graham solid oak barrel head, custom

inscribed with our names and today’s date. Before knowing about this,

we’d asked Chris if there were any way to obtain a barrel head for our

bourbon collection, and he just mumbled something about seeing what he could

do. Chris must have struggled to keep from laughing (no one knew that we

were getting these except Chris and Marnie). Naturally we’re thrilled.

Well,

it is now nearly 5:00 and we’ve spent almost seven hours intensely studying

the intricacies of this wonderful beverage. John is wondering, "Do people

who enjoy Jelly-Bellys or Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream do this sort of

thing?" Chris is wrapping everything up and getting ready for the award

presentations. Did we mention award presentations? Oh yes, as we arrived

and signed in this morning, Labrot & Graham’s lovely social director

Marnie Walters asked us to include how we’d like the course completion

award to be titled. We were expecting a diploma. We were wrong. Delightfully

wrong. As the day ends, Chris and Marnie bring out the awards and distribute

them. Each is an actual Labrot & Graham solid oak barrel head, custom

inscribed with our names and today’s date. Before knowing about this,

we’d asked Chris if there were any way to obtain a barrel head for our

bourbon collection, and he just mumbled something about seeing what he could

do. Chris must have struggled to keep from laughing (no one knew that we

were getting these except Chris and Marnie). Naturally we’re thrilled.