Maker's

Mark Distilling Company

Loretto,

Kentucky

![]()

![]()

| American

Spirits:

April 2011 -- Kentucky's Shiny Jewel |

|

|

|

|

We

first visited the Maker's Mark distillery back in 1998 (OMG, was that really

thirteen years ago?). It was the first

distillery we'd ever seen, and we really couldn't have chosen a better

introduction. We had actually intended only to visit Mammoth Cave, and

just happened to notice a sign advertising tours of Maker's Mark along the

freeway. We decided to visit on our way home.

Next day we drove north, along

scenic U.S. 31E instead of the I-65 freeway. Following the signs, we turned onto KY-52 at New Haven and

along a twisty hill-and-dale road through the beautiful rural Kentucky

countryside toward the distillery near Loretto. It was easy to let our

imaginations take us back to the days of hotrod moonshiners racing to

escape the law and deliver their contraband to a thirsty market. We could

picture Bonnie & Clyde (who did manage to drive through Kentucky on

occasion, but even if they didn't, that would be all

right... we were just fantasizing anyway) and "hear" the banjos playing

Foggy Mountain Breakdown in the background.

Next day we drove north, along

scenic U.S. 31E instead of the I-65 freeway. Following the signs, we turned onto KY-52 at New Haven and

along a twisty hill-and-dale road through the beautiful rural Kentucky

countryside toward the distillery near Loretto. It was easy to let our

imaginations take us back to the days of hotrod moonshiners racing to

escape the law and deliver their contraband to a thirsty market. We could

picture Bonnie & Clyde (who did manage to drive through Kentucky on

occasion, but even if they didn't, that would be all

right... we were just fantasizing anyway) and "hear" the banjos playing

Foggy Mountain Breakdown in the background.

Arriving at Maker's Mark

distillery did nothing to change that feeling of visual perfection. The

grounds were absolutely beautiful - every building freshly painted in the

company's dark- brown (almost black), red, and cream colors, landscaping

meticulously groomed. Our immediate impression was that if this company

puts that much care into its working environment, they must certainly put

a lot into their product.

Arriving at Maker's Mark

distillery did nothing to change that feeling of visual perfection. The

grounds were absolutely beautiful - every building freshly painted in the

company's dark- brown (almost black), red, and cream colors, landscaping

meticulously groomed. Our immediate impression was that if this company

puts that much care into its working environment, they must certainly put

a lot into their product.

Well, they do. And they always have, from day one.

Which was in 1954, about a year after T. William (call me Bill) Samuels bought a farm near the tiny hamlet of Loretto, along with what was left of the old Burk's Spring distillery located there.

Not unlike the fiefs and baronies of medieval Europe, the world of old Kentucky bourbon distillers was largely built around a handful (a rather large handful) of important families, who were involved in numerous enterprises, including each others'. To an extent, that's the way it still is, although mostly they are no longer the actual owners of the distilleries they are associated with. Certainly, the Beams come quickly to mind; members of that fine old family have been involved in just about every Kentucky bourbon distillery in existence. In many cases they played an intimate role, and that includes Maker's Mark, where Elmo Beam helped put the place together and was the first master distiller until he died.

The Samuels family is right up there with the other big guys, too. In fact, on North Third Street in Bardstown (known locally as Distiller's Row) you can see the homes, side by side, where Jim Beam's master distiller, Fred Noe, lives and where his father, the legendary Booker Noe, lived, as did his uncle, the real Jim Beam. Across the street is the home of his uncle Jack Beam (founder of the original Early Times distillery, whose bourbon became the foundation for Old Forester and, indirectly, Woodford Reserve).

Also across the street lived the Samuels family. In 1844, Taylor William Samuels, who owned a farm near Bardstown, built a commercial distillery which he called T. W. Samuels & Son (his son was W. I. Samuels). It was passed down through grandson Les until it was closed by Prohibition in 1920. The original distillery was torn down, but in 1933, anticipating Repeal, the company re-formed. The president of the new company was Robert Block, of Cincinnati, who was the chief investor, with T. W. Samuels as vice-president and Les as distillery manager (i.e., master distiller). They built a new distillery near Deatsville. Grandson Bill (also "T. William" -- dynastic families tend to pass their given names down the line along with the family names) became the manager after Les died in 1936, although his formal training was as an engineer.

In the thirties, not all bourbon distilleries were

producing product for retail sale.

The

repeal of the 18th Amendment brought about a huge vacuum of aged bourbon

whiskey and brand marketers (existing and new) were desperate to fill that

void as quickly as possible. Bourbon takes a minimum of four years to be

good, which means it was better to have a contract with a dozen little

distilleries, each cranking whiskey out a full volume, than to limit

yourself to what your one or two stills could produce in those same four

years. It was a very good time to open a new distillery in Kentucky; the

existing companies would buy every barrel you could make, as fast as you

could make it.

The

repeal of the 18th Amendment brought about a huge vacuum of aged bourbon

whiskey and brand marketers (existing and new) were desperate to fill that

void as quickly as possible. Bourbon takes a minimum of four years to be

good, which means it was better to have a contract with a dozen little

distilleries, each cranking whiskey out a full volume, than to limit

yourself to what your one or two stills could produce in those same four

years. It was a very good time to open a new distillery in Kentucky; the

existing companies would buy every barrel you could make, as fast as you

could make it.

But by the end

of the thirties, new-make whiskey began catching up with aging stock and

the market began to even out. When Les died in 1936 his son, T. W.

(Bill) Samuels (later to be Maker's Mark's Bill Samuels, Sr) became the

president. In 1938, the Samuels distillery began marketing their own brand

to distributors. It was called T. W. Samuels and it was a 4-year-old

bourbon intended for the mass market. It did very well. In fact, it turned

out to be such a big hit that shortages developed and they, themselves,

ended up buying stock from other distillers.

One of those was Labrot &

Graham in Woodford county, which they did until 1940 when Brown-Forman

(facing a similar situation) purchased it outright, mainly for its existing stock.

That was actually a pretty severe blow, and an even bigger hit came with the

distilling restrictions of World War II. In 1943, Robert Block sold the

company to Foster Trading Corporation of New York, who changed the name to

Country Distillers. According to the

Midacore Database at Pre-Pro.com and historian Sam Cecil (who was also

Maker's Mark's master distiller after Elmo Beam), it was at this time that Bill Samuels

"dissociated himself from the firm".

One of those was Labrot &

Graham in Woodford county, which they did until 1940 when Brown-Forman

(facing a similar situation) purchased it outright, mainly for its existing stock.

That was actually a pretty severe blow, and an even bigger hit came with the

distilling restrictions of World War II. In 1943, Robert Block sold the

company to Foster Trading Corporation of New York, who changed the name to

Country Distillers. According to the

Midacore Database at Pre-Pro.com and historian Sam Cecil (who was also

Maker's Mark's master distiller after Elmo Beam), it was at this time that Bill Samuels

"dissociated himself from the firm".

The official Maker's Mark story about Bill Samuels (Senior) and his motivation to depart from his family's distillery and the type of bourbon it was making doesn't emphasize that part of the history. In fact it ignores it altogether, substituting instead a story about how he disagreed with his father about their product's quality and target market, and left to form his own company, ceremoniously burning a copy of the family's bourbon recipe in the process. The fact is that he had been running the distillery for seven years since his father's death and it's somewhat doubtful that his decision to leave resulted from a disagreement with his father. One could be forgiven for believing that the disagreement was instead with the new owners who, perhaps not coincidentally, brought a lawsuit against him over his attempt to use his own name on his label. That was (or may have been, since the company won't confirm it) the real reason for coming up with a new name. Bill Samuel's son (not surprisingly, also T. William Samuels... junior) has been both the company's president and also its very prolific spokesman, historian, marketer, and -- according to some -- corporate mythmaker since 1975. When one attempts to dig into the real history of Maker's Mark, it's surprising to find how little is known that does not originate with Bill, Jr. and his association with their advertising firm, Foote, Cone and Belding, Inc. Non-local advertising for Maker's Mark began in 1983 (the Wall Street Journal, quoted in Advertising Age Sept. 12, 1983, pp 3, 54), and much of the "Maker's Mark Mystique" has been the result of those advertising campaigns and their success.

To this very day (and in fact, ON this very day, as we visit the distillery) one can "learn" that...

(1) Bill Samuels, Sr. disagreed with his father about whether to continue producing the "normal" low-quality rot-gut whiskey that most people associated with bourbon at that time, or to change to a more sophisticated, higher-quality bourbon that would command fewer sales but higher prices. Since his father had died, leaving Bill Jr. in charge, seven years before that so-called disagreement, the story is doubtful. What is NOT doubtful is that Samuels' assessment of how bourbon whiskey was perceived was dead on, and his decision to produce a new kind of top-shelf bourbon whiskey pre-dated by over thirty years the current status of "boutique bourbons". Maker's Mark's earliest advertising stressed that "It tastes more expensive... and it is". Kinda reminds us of L'Oreal's "...because you're worth it" slogan. Both are justified.

(2) Bill Jr.'s mom, Marjorie, is given credit for coming up with the name "Maker's Mark" and also the red wax image that makes the bottle look a little like the Chianti bottle candles so popular at that time. The story certainly could be true, but the only references we could find end up coming from Bill Jr. himself. On the other hand, Sam Cecil, in his book "The Evolution of the Bourbon Whiskey Industry in Kentucky" notes that both the "Maker's Mark" name and the red-wax packaging was presented to Bill Samuels in 1957 by George Shields, of the French & Shields Advertising Agency, at a meeting attended by Bill Samuels -- and by Sam Cecil himself. Cecil was, at the time, the master distiller for the company, whose product was known then as "Old Samuels".

(3) Bill Sr. spent days (months?) baking different types of bread to see what kind of recipe (mash bill) to use for his new bourbon. It's a great story, and funny, too. And while that is certainly possible, it seems much more likely that what he started with was the recipe Burk's Springs was already using for their industrial grade alcohol from wheat, modified to include at least 51% corn so as to make it legally "bourbon".

(4) Another myth about the recipe -- perhaps because it invokes another bourbon legendary icon -- is that it came (as a gift???) directly from Julian P. (Pappy) Van Winkle, the president of the Stitzel-Weller distillery in Louisville... along with the yeast to produce it. Leaving aside the idea that it's pretty unlikely that there would be any reciprocity whatever between a small, upstart country distillery in Loretto and a Louisville giant -- other than that they both would be competing for the same, relatively small group of elite consumers, we already know that their original distiller was a Beam (Elmo), and it's more likely that he brought his version of the Beam yeast with him. (Will McGill was the distiller at Stitzel-Weller, and it was his yeast they used there; Pappy Van Winkle was a businessman, not the distiller ).

There are many other examples. Bill Samuels, Jr. was, and remains, perhaps the single most genius marketer of bourbon whiskey that ever came down the pike. Whether his father was the visionary that Bill portrays is immaterial. A lot, a whole lot in fact -- maybe more than half -- of our enjoyment of bourbon is based on the mythology we feel when we drink it. Bill didn't invent that fact; it's been around from the beginning. But he has expanded on it, and made it accessible, even funny. Some of the best advertising ever has been Maker's Mark ads, certainly some of the best whiskey ads.

Perhaps even more interesting and important is the

appointment of Victoria MacRae-Samuels to the position of Vice-President

of Operations. This is yet one more example of how the Kentucky bourbon

dynasties continue to inter-relate and influence the whole of the Kentucky

whiskey world.

She is taking on the work of not only running the

distillery itself, but developing and promoting both Maker's Mark and their first new

product since their inception in 1953 -- Maker's Mark 46. Unlike Bill

Samuels (any of them) Victoria didn't arrive at her position because of

her familial ties. Although she is, indeed, married to Bill Samuels'

cousin, the relationship is actually distant. The beginnings of her

connection with the world of bourbon whiskey came with her appointment by Booker Noe of Jim Beam

to a position as a research and development chemist there. Working at both

the Beam's Boston and Clermont distilleries, she developed

analytical testing processes that are now industry standards. In 1997 she became their

product processing manager, essentially charged with "inventing" whatever

whiskey types the marketing department deemed necessary. That included

over 30 products, among which were the "Small Batch Collection". In 2005,

Beam Global purchased Allied Domecq, the British company that owned

Maker's Mark at the time, and thus became the owners of this little

distillery in Loretto. Guess who got sent down to Maker's Mark to finish

the production and to introduce the only new brand of whiskey ever released

by that distillery since its inception. Yup, it was Vicky. She and master

distiller Kevin Smith are responsible for the production of all Maker's Mark bourbon -- from

grain selection, fermentation, and distillation to barrel warehousing,

bottling and shipping, taste testing, and quality control.

She is taking on the work of not only running the

distillery itself, but developing and promoting both Maker's Mark and their first new

product since their inception in 1953 -- Maker's Mark 46. Unlike Bill

Samuels (any of them) Victoria didn't arrive at her position because of

her familial ties. Although she is, indeed, married to Bill Samuels'

cousin, the relationship is actually distant. The beginnings of her

connection with the world of bourbon whiskey came with her appointment by Booker Noe of Jim Beam

to a position as a research and development chemist there. Working at both

the Beam's Boston and Clermont distilleries, she developed

analytical testing processes that are now industry standards. In 1997 she became their

product processing manager, essentially charged with "inventing" whatever

whiskey types the marketing department deemed necessary. That included

over 30 products, among which were the "Small Batch Collection". In 2005,

Beam Global purchased Allied Domecq, the British company that owned

Maker's Mark at the time, and thus became the owners of this little

distillery in Loretto. Guess who got sent down to Maker's Mark to finish

the production and to introduce the only new brand of whiskey ever released

by that distillery since its inception. Yup, it was Vicky. She and master

distiller Kevin Smith are responsible for the production of all Maker's Mark bourbon -- from

grain selection, fermentation, and distillation to barrel warehousing,

bottling and shipping, taste testing, and quality control.

In the spring of 2011, after 35 years as president of Maker's Mark, Bill Samuels Jr. retired at the age of 70, handing the reins over to his son, Rob. In announcing his retirement, Bill was quoted as saying "It's pretty obvious to me and anybody else around here that at 36, Rob is a whole lot more qualified than I was at the same age, and I took over at 35,"

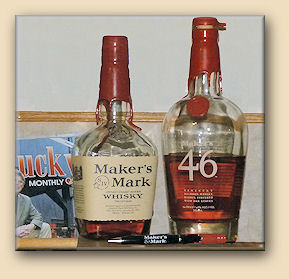

Oh, by the way, did you notice that we made a reference to

"Maker's Mark 46"? This is first new brand introduced by Maker's Mark since it

began in 1954. They call it their "second big idea". Other distilleries introduce new brands all the time, some

of them releasing a new version every year. Not Maker's Mark. Their concept of themselves (at least their public image) has always been

that they carefully created the finest example of bourbon whiskey that

could be made and they make it. No need to change anything; it's already

perfect just the way it is. Nice idea. Unfortunately an ever-increasing customer base

expects something new and different. How are you supposed to provide

something "new and different" when you are already making the best bourbon

whiskey you know how to make? After nearly sixty years, Maker's Mark has

finally come up with an improvement worthy of releasing as another brand.

When Bill

Samuels, Sr. created Maker's Mark in 1953, his object was to challenge the

then-accepted definitions of just what "bourbon whiskey" was supposed to

be. Bourbon (with a few exceptions -- notably Stitzel-Weller's Old

Fitzgerald) was a rough-and-tumble liquor marketed primarily to

working-class (and below) customers, and a few aficionados and elected

officials who either sought the support of such folks or reveled in the

idea of enjoying "forbidden" things. It was Samuels' (not sure just which

Samuels) idea that bourbon whiskey could be make socially

acceptable, and even sophisticated. Samuels positioned his product to

target consumers who wouldn't otherwise have been caught dead drinking bourbon, and he

succeeded. He wasn't afraid to use a non-conventional recipe. He most

certainly wasn't afraid to advertise unconventionally.

And

with the new product, nothing about that has changed.

And

with the new product, nothing about that has changed.

You say you'd like to try something that is like Maker's Mark, but better? Okay, here's what we'll do... we'll take Maker's Mark -- the exact same Maker's Mark you already love -- and make THAT better.

Of course, there are always "me-too"s, but the core of any new expression of an existing product is its ability to provide something genuinely new, or (even better) a step up from the existing level of excellence. What Maker's Mark 46 does is just that, and in its purest form. The "existing product" that it uses for its base is pure Maker's Mark, barrel-aged to perfection and just as it would be ready to bottle... and then brings that barrel to a higher level. They accomplish this by using a technique so radical that no other distillery has done that... at least not since Prohibition. Well, at least no MAJOR distillery; several tiny, independent, "craft" distilleries have experimented with similar ideas, but no multi-billion dollar corporations have tried it yet.

Except Maker's Mark. What they do is to take barrels of regular 6 to 8 year old Maker's Mark, dump them into a cistern, and then take the barrels (yes, the same barrels the whiskey came out of) and add to each one an intricate array of toasted, but not charred, French oak slats, ten of them, mounted on plastic rails. With the barrels now converted, they then refill them with the same bourbon that came from them and allow them to sit and age for another three to five months. The result has all the characteristics of Maker's Mark and a noticeable second dimension not present in the original product -- nor in anyone else's. It is easily identifiable as Maker's Mark, while also different enough to justify itself as a separate brand. It took many attempts to get just the right combination of technique and process; forty five of them, to be exact. The final selection is this one, number 46, and hence the brand name.

Click here for more and larger photos

So, is it any good? Well, that's for you to decide. Maker's

Mark is a sophisticated bourbon that appeals to people who prefer its

subtleties over the distinctive (and sometimes overpowering) taste of both

lesser-quality and also richer-quality bourbons. As a transition, it fits

perfectly. And for those who feel Maker's Mark is, perhaps, a bit too tame

for their changing tastes, but for whom something like Booker's or Old

Weller is just too much, Maker's 46 might be just what the doctor ordered.

Maker's Mark also produces special bottlings of it's normal bourbon. Known for their trademark red-wax sealings, they regularly offer bottlings dipped in various college colors, which are (of course) very popular. They released a series of bottlings dedicated to horseracing triple-crown winners and also a lovely red-white-and-blue patriotic bottling, done one time only, in recognition of the heroes and victims of the 9/11 tragedy. Like some other distilleries, Maker's Mark offers special bottlings that one can purchase and put custom labels on them for gifts or display, but these are not just labels; the bottles themselves are lovely, cut-glass-type back-bar bottles, worthy of any collection.

So here we are, visiting Maker's Mark distillery again. Our first impression is that it looks just the same, although there are a few differences. For one thing, the building that was once the tollgate house is now a restaurant. That's a great idea; we wish we hadn't had lunch earlier, because it looks like a great place to grab a sandwich after the tour.

Another is that the gift shop has been separated from where

the original distillery office used to be and moved to another

building. The original office is now the start of the tour, as it was

before, but there are now some other features that are entertaining.

Where

the gift shop used to be is now a reproduction of a typical 1950s kitchen,

the idea being to help guests image how

Where

the gift shop used to be is now a reproduction of a typical 1950s kitchen,

the idea being to help guests image how

Bill

Samuels pictured his dad inventing a bourbon recipe while his mom came up

with the red-wax bottling technique and trademark. The nostalgia is

perfect for John (although it predates Linda somewhat -- she didn't exist

before the mid-'60s).

Bill

Samuels pictured his dad inventing a bourbon recipe while his mom came up

with the red-wax bottling technique and trademark. The nostalgia is

perfect for John (although it predates Linda somewhat -- she didn't exist

before the mid-'60s).

Click here for more and larger photos

Our tour guide is Mike. And like most tour guides, he has

been well-trained and scripted. But he is comfortable with the script and

he's lively and entertaining (that isn't always the case with tour

guides), and even better, he can answer questions without becoming

confused (also not always the case). Mike takes us first to the distillery

building itself. Inside is "the" still, a relatively small, 16-plate

all-copper column still which is not in service at this time. That's a

shame, because that means the lovely brass 'n' glass "safe boxes", where

the "white dog" new whiskey pour out, ready to be tested -- and tasted --

are also not functional. Maker's Mark's visitor display is lovely and

probably the very best introduction possible for people who enjoy bourbon

and want a pleasant (if somewhat superficial) tour of just how it's made.

Perhaps there is a more comprehensive tour for purists and dedicated

(read, obsessed) fans like us who would like to see behind the curtain,

but that's not we're seeing today. That's okay; this is not that sort of a

tour. We'd just like to have one available that is.

And it's a very pretty "curtain", indeed. The folks at Maker's Mark aren't trying to "fool" anyone; The distillery tour here is designed to be an "introduction" for folks who are just beginning to become interested in how bourbon is made. And as such, we believe -- as we always have -- that it is likely to be the best introduction tour of any.

For example, our guide Mike notes that the lovely old

cypress fermenting tanks (there are eight of them, each holding 9,600

gallons of bourbon mash) are basically for display, and that the other

fermenting tanks are in another part of the distillery. They are made of

stainless steel, also holding 9,600 gallons apiece; and there are 29 of

them.

There are rumors that there are other column stills, as well, which should not be surprising, as we have seen at least a dozen brand-new Maker's Mark warehouses in other parts of Marion and adjacent counties.

We're not certain whether the whiskey in those other

warehouses is treated the same way, but here in Loretto the barrels are all rotated regularly, by hand. That's a process that was once common but,

as far as we know, is now performed only

at Maker's Mark. The idea is that whiskey barrels, which are profoundly

affected by weather and temperature, age quite differently depending on

whether they are on the lower tiers of the warehouse, the middle, or the

upper part. By continually moving barrels from one area to another, even

from one warehouse to another, the

aging process of each individual barrel can be precisely controlled, in

addition to the fact that the rolling of the barrel itself lends to the

aging process. It's a labor-intensive (and expensive) process, but that's

what they do here. All of that is accomplished by hand; there are no

forklifts at Maker's Mark. After fully aging, the bourbon is ready for

bottling -- or, if it's going to become "46", re-barreling into the

"staved" barrels for another 3 to 5 months.

Click here for more and larger photos

Mike also takes us to the bottling house. This is probably

the biggest surprise for us. When we were here nearly a decade and a half

ago, the bottling line was a tiny setup, with a few women filling,

bottling, labeling, and wax-dipping bottles. There was machinery-green

equipment and lots of boxes that we had to weave among as we walked about.

Today we find ourselves in a world of glass and stainless steel, where

everything is cleaner, brighter, and much more modern. Unfortunately, like

the distillery itself, the bottling line is also not in service at this

time. So

all we can see are empty stations.

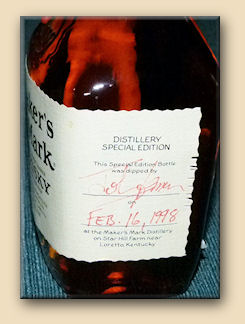

When we visited here before, we decided to purchase one of the small (375ml) bottles available for sale at the gift shop. These bottles have a special label that identifies them as being from the distillery store, and they also have a place for the purchaser to sign and date the label. The bottles come without the trademark bright red sealing wax, and the customer can then hand-dip their own bottle. We remember that John chose to do this. He donned the required apron, safety goggles, and gloves. Of course, the women who dip the production bottles, 24 per minute, on the bottling line wear none of those. John's bottle came out just fine, with the wax running perfectly down the side of the neck. We still treasure it as an important part of our collection.

|

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright ©1998 & 2011 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |