American

Whiskey:

April

28,

2011

--

Kentucky's New

Distillers

M. B. Roland Distillery

Saint Elmo, Pembroke, Kentucky

-

Mistakes, errors, and last-minute scrambles to recover from them.

-

Blind faith, and blind chance… along with survival of the fit (or the lucky).

-

Tradition, passed down by rote, from one barely-cognizant generation to an obedient, but otherwise clueless generation.

Those sure don’t seem to be elements of a formula for success, or quality. And they aren’t. But that’s the romanticized image that the distilled spirits industry loves to promote. Why? Probably because that image hits a chord with what they think of as their core customer base.

Okay, we recognize the concept; heck, it hits a chord with us, too. But we’re not completely sure we buy into all that, although it might have been how American whiskey originally developed. What we do know is that today’s small distiller is far, far away from such ideas. Thanks to the legacy of laws and local traditions that followed National Prohibition – and which remain to this day – anyone who harbors a fantasy about becoming a distiller of American whiskey (or any other spirit) had better have a pretty good understanding of just what she (or he) is getting into… and what can be expected (or at least hoped for).

One very good example of today’s distiller is Paul Tomaszewski, an ex-Army infantry officer and West Point graduate from Louisiana, who, around 2005, decided that he’d prefer to be a farmer/distiller instead.

Not just any ol’ farmer/distiller, you understand… a Kentucky farmer/distiller. A whiskey distiller, and a bourbon distiller, for sure, but not necessarily limited to what we’ve come to think of as that kind of whiskey.

Paul is really into

whiskey – American whiskey, the way real Americans really used to make and

drink it. Sure, it’s true that the product that was the most commercially

successful way back then (meaning at the beginning of the 19th century) was whiskey (corn or rye) that had been aged in

wooden barrels and made to resemble New England rum (which was suddenly no longer

available) or

French Cognac (also

suddenly scarce),

but few (if any) of a distiller’s local customers ever tasted anything like

that.

In fact, if a local tavern owner tapped a new barrel of whiskey

and found it to be brown, he’d probably have sent it back, along with a

demand for a refund. Most producers of Kentucky (or Pennsylvania) whiskey had

no idea that their product would change so dramatically by the time anyone

in Boston, Baltimore, or New Orleans ever partook of it. Local customers

expected their whiskey to be clean and clear, not brown. And, despite

popular “hillbilly” mythology, local customers were not ignorant; they had a

pretty good idea of who was making a high-quality product, and who wasn’t.

In fact, if a local tavern owner tapped a new barrel of whiskey

and found it to be brown, he’d probably have sent it back, along with a

demand for a refund. Most producers of Kentucky (or Pennsylvania) whiskey had

no idea that their product would change so dramatically by the time anyone

in Boston, Baltimore, or New Orleans ever partook of it. Local customers

expected their whiskey to be clean and clear, not brown. And, despite

popular “hillbilly” mythology, local customers were not ignorant; they had a

pretty good idea of who was making a high-quality product, and who wasn’t.

Paul Tomaszewski makes high-quality Kentucky whiskey. Except for some early experiments with rum (also an American spirit, though that fact is often overlooked), the spirits he makes are entirely whiskey, or spirits made from or with whiskey. He’s aging some of it, so there will eventually be high-quality aged M. B. Roland whiskey (he's already released an aged bourbon and a malt whiskey, but they've sold out of both. There will be more when it's ready. Paul is patient; we'll just have to be, too). But one of many things that sets him apart is that aged whiskey is not his total focus. Paul makes, and markets, a variety of unaged whiskies, along with other spirits and liqueurs made from unaged whiskey. And every one of them is the result of a great deal of thought and understanding about the historic place of whiskey in a land where whiskey is part of it’s own definition.

Today, we are

visiting him at his M.B. Roland distillery. Located on his farm in the

village of Saint Elmo, just outside of Pembroke, Kentucky, it is named for

his wife, Merry Beth.  The dawn of the 21st century has brought

forth a renewed interest in the distilling of spirits in America, as dozens

of would-be Glenfiddichs or Buffalo Traces or Jack Daniels’ try to establish

themselves. We certainly wish each of them the best of luck. But, as folks whose

interest in American spirits runs so very close to our interest in America’s

social

heritage, we have a special place in our hearts for people such as Paul and

Merry Beth. Because, while other new distillers often release unaged whiskey

or spirit as an interim product, while they await the aging (sometimes

forced) of what they consider their “real” stuff, the Tomaszewskis are

producing – and successfully marketing – several expressions, based on

unaged spirit (including, but not limited to, whiskey), just as the

farmer-distillers of the 18th and early 19th century

must have. At least the more knowledgeable ones.

The dawn of the 21st century has brought

forth a renewed interest in the distilling of spirits in America, as dozens

of would-be Glenfiddichs or Buffalo Traces or Jack Daniels’ try to establish

themselves. We certainly wish each of them the best of luck. But, as folks whose

interest in American spirits runs so very close to our interest in America’s

social

heritage, we have a special place in our hearts for people such as Paul and

Merry Beth. Because, while other new distillers often release unaged whiskey

or spirit as an interim product, while they await the aging (sometimes

forced) of what they consider their “real” stuff, the Tomaszewskis are

producing – and successfully marketing – several expressions, based on

unaged spirit (including, but not limited to, whiskey), just as the

farmer-distillers of the 18th and early 19th century

must have. At least the more knowledgeable ones.

As we drive up the

graded gravel road to the distillery, we encounter a sign that alerts us to

be careful not to run over any cats. Paul and Merry Beth are assisted by

over a dozen “distillery cats” who roam the area. Distilleries are also

grain storage centers, and that means they are popular with grain eaters,

such as mice. Cats enjoy mice. They make fun playmates, and when you are

finished playing, they become lunch. The cats at M. B. Roland appear to be

enjoying an abundant diet of filet d’ mouse. Life as a distillery cat

is very good indeed. By the way, all of the cats also enjoy first-rate

veterinarian services, which has included processes that discourage other

cat-like activities – such as producing more cats.

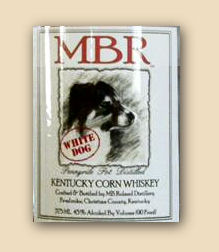

The Tomaszewski’s also have at least one pet dog, a border collie named Cassius, who is their brand’s mascot and symbol. Cassius is a border collie (John’s favorite breed, by the way) who they rescued from a local shelter and who serves as “spokesdog” for the brand. It is his photo that graces the label of their White Dog and Black Dog products. We would have enjoyed meeting him, but today is apparently his day off.

In his place, we

have been “assigned” to “Bourbon”, our assistant tour-guide today. Bourbon

is a lovely black-furred lady of the feline persuasion who is quite vocal,

and enjoys (demands, actually) frequent physical contact with humans.

When we first enter the visitor center, we are met by a lovely (human) lady with the most beautiful Luz’anna accent. She is vacuuming the floors as we arrive. As it turns out, she is Paul’s mother, who is visiting from Louisiana. Like ours and everyone else’s mother we know, she has decided that her son’s place needs just a little straightening up and she is busy doing that.

Paul is outside talking to a vendor, but he shows up shortly. In the meantime, another couple have arrived to see the distillery. Their son, who is returning from Afghanistan this evening, shares with Paul a commission with the Army and graduation from West Point, albeit a few years later.

We originally met Paul, and Merry Beth, at a tasting demonstration that they conducted earlier this year at our favorite liquor store and entertainment emporium, The Party Source in Bellevue, Kentucky. The world of American craft/artisan distilling is exploding right now, and we neither can, nor want to, examine each and every one of the new distillers. After all, most have their own web pages and facebook accounts. But there are a few that we feel really NEED to be included in a website dedicated to the history of American spirits, and we believe M. B. Roland is one. Why? Because Paul Tomaszewski is focusing his efforts on the kinds of products that might have been successfully marketed by American grain farmers of the 19th century, had they taken that direction instead of producing aged spirits.

It is our belief that the actual producers of distilled grain spirits, mostly in western Pennsylvania and Kentucky, never realized that the clear white spirits they sold to merchants in places such as Louisville, Crab Orchard, Greenville, and other frontier merchant centers would become the ersatz rum and brandy that was retailed in New Orleans, Baltimore, Philadelphia, or Boston. Their local customers expected fresh, un-brown, grain-flavored whiskey, or variations of that, perhaps with pumpkin, or mint, or apples infused. Had M. B. Roland been around in those days, they would have got that. Who knows, perhaps there WERE producers of spirits such as those. At any rate, there is today, and we are here to celebrate it.

Paul is a very sharp guy. He knows exactly how to produce the spirits he does, and he knows how to produce spirits he doesn’t do – at least at the moment. Unlike many new “distillers” (and an embarrassing number of famous “old” distillers), he really is the master distiller here. In fact, he is the only distiller here. Is he a biochemist? Hardly. In fact, he jokes that his chemistry instructor would have never guessed he’d ever successfully made use of anything taught to him in that field of endeavor. But you can’t distill well if you don’t know what you’re doing, so he learned about it. A lot about it. And, while he is certainly more “hands on” than “book-learned”, Paul is probably more knowledgeable than most distillers we know, young or old.

Okay, so making good spirits is one thing; marketing good spirit products is another. And this is where talent shows itself. Paul’s marketing is, perhaps, the most interesting thing about M. B. Roland. He is slow and methodical. But at the same time his concentration is always on the leading edge of what he’s already doing, so public familiarity with the products and the brand is always, always expanding. He does demonstrations and tastings (that’s how we met him); he uses the Internet and social networking; he enters his products in competitions (our first experience with MBR was at an American Distillers Institute conference, where they won a medal). He will go anywhere and do anything to promote his products.

And the products are diverse. Paul not only differentiates between “moonshine” and “white dog”, but actually markets both types of unaged spirit. He also produces another, unique form of unaged corn liquor made with corn that has been smoked in a tobacco barn to produce a type of whiskey that can only be described as reminiscent of what unaged Islay Scotch might taste like, to those lucky few locals who can obtain any. Paul markets it to the public; it’s called, not surprisingly, “Black Dog” (hello, Jimmy Page). Anyone interested in whiskey history – American or European – should seek this out and buy a bottle (or two).

MBR’s corn liquors

(that is, their white and black “dogs” and their bourbons) are made using

only sweet white corn, sourced from farms all within five miles of the distillery, not the #2 yellow

feed corn that is standard for the industry.

According to bourbon historian Michael Veach, white corn was the original

grain of choice for the best bourbon whiskies, and at least one major

whiskey distiller, Buffalo Trace, is now aging barrels of white corn bourbon

according to Edmund Taylor’s original recipe. MBR is also aging some of

their product, and it, too, is a white corn bourbon (that is, it contains

some rye and barley malt along with mostly white corn). All of Paul's whiskies are distilled to an

honest 100 proof (50% ABV), and bottled at either that or cut

only to 90 proof

Paul has another unaged corn product, but it isn't whiskey. He calls it "True Kentucky Shine", and what it is... is legal moonshine.

"But wait!" you say. "I thought 'white dog' was 'moonshine'. Aren't they the same thing?"

Don't feel bad. You're about to learn something that most folks don't know. Many people who enjoy unaged corn whiskey, even drinks writers who ought to know better, tend to call any white whiskey "moonshine", or just 'shine. But that isn't true, and not just because what you're likely to find in a bar or retail store is tax-paid and legal, but also because 'shine is made differently. Really, it's not a type of whiskey at all; it's a kind of spirit with its own characteristics. And like just about everything else, there's cheap, rot-gut 'shine and there's good 'shine. The bad stuff is made completely from cane or beet sugar and is everything you've read about the horrors of moonshine whiskey (except that it isn't whiskey; it's more like really bad rum). That doesn't mean, though, that there isn't good 'shine. The world of distillers whose operations have not been blessed by the licensing and taxing authorities has existed for as long as alcohol has been produced. Many distillers who'd just as soon you not know their names are justifiably proud of the 'shine they make... at least for themselves and their close friends. Good 'shine is made with corn and sugar, and has a quality of both new-make whiskey and new-make rum, and perhaps new-make cognac as well. It doesn't taste like white dog -- at least it shouldn't. Paul makes it from a mash of 50% white corn and 50% sugar, and he intentionally distills it out to a much lower proof than would be expected (110-proof) to bring over the flavor into the spirit. He says he sells more of it than he does the white dog.

He also uses it as the base for many of his specialty beverages. He makes a strawberry 'shine, a blueberry 'shine, a lemonade, and wonderful Apple Pie 'shine. They're all made the way people used to make them (and still do, except now you can buy them legally), by mixing moonshine with fresh fruits, berries, and spices.

When we saw him earlier, Paul

let us taste a sample of a product he is currently working on (well,

'waiting on' is probably a better word), barrel aged True Kentucky Shine.

It's

hard to compare it with his aged bourbon, because it really isn't ready yet,

but we can already tell this will be another example of an American spirit

completely different from bourbon. We also tasted a sample of the Black Dog

that is aging in used bourbon barrels. He's going to call that one Black

Patch.

It's

hard to compare it with his aged bourbon, because it really isn't ready yet,

but we can already tell this will be another example of an American spirit

completely different from bourbon. We also tasted a sample of the Black Dog

that is aging in used bourbon barrels. He's going to call that one Black

Patch.

So, as we begin the the tour itself, the first thing we notice is that we feel more like we're visiting a friend who makes whiskey than touring a whiskey factory. The visitor center is warm and inviting and, thanks to Paul's mom, the floors are even cleaner than they probably usually are. The room includes a tasting bar and several displays of available product, but it’s very low-key and pretty much they way you would put such a thing together in your own spare room. Actually, it's a bit more than that; there are displays of their products, of course, but also displays and examples of artisan work by several other local craftsmen. The distillery itself is contained in a single barn-sized building across the parking lot from the visitor center. It's a one-room affair with work areas and storage, and in one corner stands the still. It is a very small (only 100-gallon capacity), but beautiful, copper pot still standing on a small “stage”, surrounded by bottles and carboys of recently-distilled spirit. The still once had a column attached for alcohol-stripping, but Paul decided it wasn’t necessary for his purposes and had a “gooseneck” built to replace it. This gives him just the amount of condensation, or reflux, that he wants and is much closer to the way real “moonshine” is made. Not coincidentally, it’s also much closer to the way classic Scotch and Irish whiskey is distilled, not to mention classic American bourbon and rye.

When we arrived at MBR, we parked in front of a building with tarp sides that is connected to a barn-like structure. Back when this was a farm, these buildings were used to dry tobacco. Paul continues to use these buildings, but now he is drying, or rather smoking, the white corn used to make his “Black Dog” whiskey. The result is a white whiskey that has a distinctly smoked flavor. It is reminiscent of what might once have been an attempt at re-creating peated Scotch (and that’s how Paul sees his product), but which seems even more intriguing as a type of “Barbequed Bourbon”. We feel this particular spirit would be an ideal addition to any barbeque or tail-gate party. It would also be very appropriate to serve with a fine grilled steak, instead of Bordeaux wine.

After the tour, we spend some time sharing samples of long-gone whiskies we brought with us and some experimental and not-yet-released spirits that Paul is working on. MBR is, as should be expected, expanding the range of states where it is available. But not only will its current products be available in more markets, it is also expanding the number of products they make. Paul Tomaszewski is a man who has a pretty clear idea of how to market his product, and that means you can expect to find several examples of MBR spirits either soon or already.

You need to try them.

|

|

|

Story and original photography

© 2011 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|