American Whiskey

Rye Distilleries of Eastern

Pennsylvania & Maryland

February

19, 2006

Mount Vernon Rye

1872 - ~1906:

|

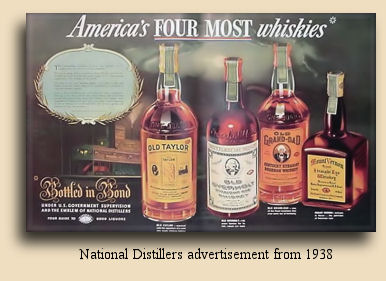

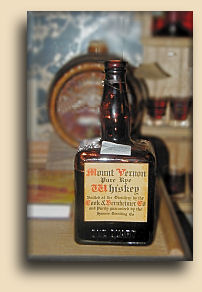

MOUNT VERNON IS PROBABLY the most widely-known brand of Maryland Rye.

It's distinctive square bottle is easily recognized, and it was one of National

Distillers' Big Four brands well into the late 1950's. Even in its

pre-Prohibition incarnation, Mount Vernon took first-place awards at no less

than four World's Fair competitions (Philadelphia in 1876, New Orleans in 1885,

Australia in 1887, and Chicago in 1893) making it one of the Baltimore liquor

and distilling industry's premier products. Unlike most of the Baltimore brands,  Mount

Vernon remained active throughout Prohibition as medicinal whiskey, released

through American Medicinal Spirits.

Mount

Vernon remained active throughout Prohibition as medicinal whiskey, released

through American Medicinal Spirits.

It's likely those factors were taken into account when AMS reorganized itself after repeal and needed to select which brands would be promoted and developed by the new National Distillers company. They chose Mount Vernon for their brand of Maryland Rye (Old Overholt was selected as their Pennsylvania Rye ).

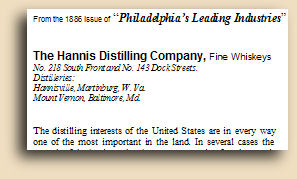

Given all that, one can hardly help being amused by the fact that

the Hannis Distillery's general offices were located in Philadelphia, not

Baltimore, that Mount Vernon was somewhat of a specialty brand they made at

their Baltimore distillery, but most likely was not their main product line.

Perhaps a little like imagining Woodford Reserve Kentucky Bourbon as being

Brown-Forman's main brand... while ignoring their massive distillery in

Tennessee where they produce Jack Daniel's, the largest-selling American whiskey

in the world.

The original Mount Vernon distillery #1, at the corner of Russell and West Ostend streets

in the southwest part of Baltimore,

was built in 1863 by Henry S. Hannis & Company, of Philadelphia. Actually,

it was re-built by Hannis, who bought an existing distillery which

had been operated there for over a decade by Edwin Clabaugh and George Graff and

had it enlarged and modernized. Just how "modernized" you ask? Well, when

the United States held the biggest "look what we've accomplished!"

show it its history, the 1876 Centennial Exposition, a key exhibit at the

Agriculture Building was a model whiskey distillery, displaying the state of the

art in world-class terms (it's certainly hard to imagine such a public

acknowledgement of the beverage alcohol industry today).

And

selected for that honor was the new Hannis distillery in Baltimore, whose design

was reproduced for the display.

And

selected for that honor was the new Hannis distillery in Baltimore, whose design

was reproduced for the display.

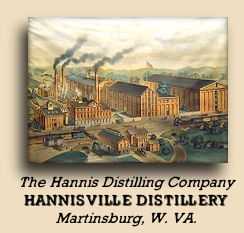

Hannis' use of high-tech processes didn't stop with the Centennial Exhibition, nor with Mount Vernon Rye. That brand was only one of several lines of fine whiskeys, as well as medicinal alcohol, produced by the Philadelphia-based company. And in 1871 they built a huge new facility in Martinsburg, West Virginia to produce most of them. At that time they also changed the company name to The Hannis Distilling Company. Mount Vernon Rye, by virtue of its having been recovered from the void after national prohibition, is only the most familiar brand, not necessarily their most important one. Other of their brands included Hannis Copper Distilled Pure Rye, Acme X, Tidal Wave, and Victor. Mount Vernon Rye appears to have been made only at the Baltimore distillery, but as is common with so many of these old brands, all may not be exactly as it seems.

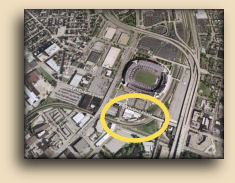

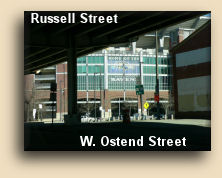

As we head out this morning to see what has become of the area it becomes clear that we will not be finding distillery remains here. We can't even find the corner. That's because technically there isn't one. Oh, Russell Street and Ostend Street still intersect, all right. It's just that they do so in another dimension, about twenty feet overhead. There have been a few changes since Hank Hannis and the boys were boiling the alcohol out their rye mash in this corner of Baltimore. The Camden Yards baseball park, and the Baltimore Ravens' stadium occupy much of the area, with parking lots just off Ostend. Russell Street is now a multi-lane, raised-level highway, which descends to street level right after crossing over Ostend.

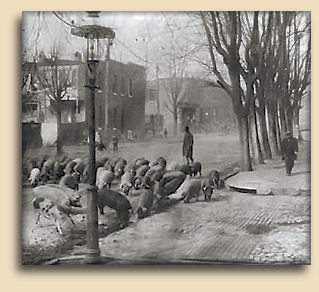

While driving around the area, we notice there is a neighborhood

called "Pigtown". Not insultingly, you understand; the citizens here are proud

of their neighborhood and of its history. In fact, our discovery of it was by

way a large welcoming sign as we entered it. They even have an annual pig

festival. The official history of the neighborhood (also known as Washington

Village) suggests that it got its name because pigs (and cattle, too, but mostly

pigs) arriving at the nearby Pratt St. B&O railroad station were herded through

the town on their way to the Federal Hill and South Baltimore slaughterhouses. This practice continued into the late 1930's, and it makes one wonder how even

non-PETA lovers of bacon and ham could stand the noise, the filth, and

especially the smells.  But apparently the idea of building an annual civic

promotion around it smelled just fine to managers of the Washington

Village/Pigtown branch of Main Street, a public community development

group, and beginning in 2002 they have organized and staged the Annual

Running of the Pigs Festival. The event has been very successful and a

good time is had by all... even the pigs. In order to get the first year's run

going, the festival relied upon the generosity of a dean at the University of

Maryland Agriculture Department, who lent the organization 18 of his personal

pet pigs. And ever since then, the same 18 pigs have been trotted out (so to

speak) for the event.

But apparently the idea of building an annual civic

promotion around it smelled just fine to managers of the Washington

Village/Pigtown branch of Main Street, a public community development

group, and beginning in 2002 they have organized and staged the Annual

Running of the Pigs Festival. The event has been very successful and a

good time is had by all... even the pigs. In order to get the first year's run

going, the festival relied upon the generosity of a dean at the University of

Maryland Agriculture Department, who lent the organization 18 of his personal

pet pigs. And ever since then, the same 18 pigs have been trotted out (so to

speak) for the event.

Okay, right about now you're probably asking yourself, "What on EARTH is John TALKING about? What do PIGS have to do with anything, for cryin' out loud?"

Well, you'd be correct about one thing: yes this is an excursion that John is doing alone; Linda couldn't be here today to search for where the Mount Vernon distillery isn't anymore. And your suspicion that Linda wouldn't have done this to you is also well-founded. Bless her.

But there really IS a reason John brought up the idea of Pigtown. It's because he's been trying to find the location of places that faded away or turned into something else long ago. And that sometimes involves asking folks for information. Unfortunately, asking for information about distilleries often brings only a denial of any knowledge, followed by an assurance that the person has never intentionally partaken of any intoxicating liquor, although they may vaguely remember a relative or associate who tried it once.

However, the same people will gladly tell you where the local pig farms or stockyards are or were.

And if there were ever a distillery in an area where you see the word "pig" applied to a location, you'll almost certainly find evidence there of the old site. Alcohol makes up only about eight percent of fermented whiskey mash (called "distiller's beer"), and if it's sour mash (which Maryland ryes such as Mount Vernon weren't) another 25% or so "setback" to start up the next batch. That's really the only part the distiller is interested in. What do you suppose he does with the other 65-92% of protein-rich, high-fiber grain meal? Distillers -- at least whiskey distillers -- NEED pigs, or cows, or some animal that can turn a "plant" asset (actually a "used plant" liability, as in "spent-grain") into a "meat" asset. Distilleries nearly always work in close cooperation with pig farms, feedlots, or slaughterhouses. Often a successful distillery, one that operated more or less continuously, would have its own pig farm or feedlot.

So... in an article he wrote for the April 15, 2005 edition of the Baltimore Sun, author Michael Anft interviewed Buss Chambers, a 77-year resident of Pigtown, who could recall seeing some of the real "runs", back in 1932 or '33. Actually Anft says his eyewitness told him they might better be described as "pig walks" or waddles. "They didn't move too fast," Chambers told Anft. "One guy who I guess was a pig herder had a long staff to keep them in line... If one or two pigs ended up on the pavement, one of the older men would snatch one through a basement window."

And then Chambers speaks of the route. He said the pigs were driven along Bayard Street, then made a left turn onto Hamburg Street and a right turn on Ostend, before crossing a bridge into the packing house district.

The Hannis Company's primary distillery at Martinsburg had been

shut down and dismantled a dozen years earlier than the run Chambers witnessed,

of course.

But

the Baltimore plant continued to make medicinal whiskey all through prohibition.

This wasn't constant production. Stocks of medicinal were sold by prescription

constantly from bonded warehouses, but distilling to replenish those depleted

stocks was only authorized on an as-needed basis. That meant that distilleries

operated sporadically, and therefore an onsite pig farm was not an option. And

that meant Hannis had to arrange for disposal of the wastes as needed.

But

the Baltimore plant continued to make medicinal whiskey all through prohibition.

This wasn't constant production. Stocks of medicinal were sold by prescription

constantly from bonded warehouses, but distilling to replenish those depleted

stocks was only authorized on an as-needed basis. That meant that distilleries

operated sporadically, and therefore an onsite pig farm was not an option. And

that meant Hannis had to arrange for disposal of the wastes as needed.

Pigs are shipped to the meatpackers every day. But the pig runs through the streets weren't daily occurrences. They were events which happened only once in awhile, and were a big-enough deal that everyone noticed and anticipated. Buss Chambers remembers, over seventy years later, what he saw as a five-year-old child, and even what year it was.

So when the Hannis still was scheduled to produce whiskey, they

would arrange a diversion from the normal livestock delivery routine, so as to gain

a temporary visit from the traveling waste-removal engineers (oink!). John

follows the route on a map.

Sure enough, those hungry pigs waddled their way right down Ostend Street, from

Hamburg to Wicomico, then on past Scott, Paca, Burgundy, Ridgely, Russell, and

then over the bridge to Federal Hill. MMMmmmmm GOOD! And now John knows exactly which side of an intersection

that no longer exists once stood a distillery that's no longer there.

Sure enough, those hungry pigs waddled their way right down Ostend Street, from

Hamburg to Wicomico, then on past Scott, Paca, Burgundy, Ridgely, Russell, and

then over the bridge to Federal Hill. MMMmmmmm GOOD! And now John knows exactly which side of an intersection

that no longer exists once stood a distillery that's no longer there.

Parking the car in a convenient commercial loading dock John

points his camera toward a location where, a long time ago, Henry Hannis and his

company made Maryland Rye Whiskey.

Of

course the end of prohibition meant the return of that popular brand to full

production capacity, which meant that the little distillery would no longer be

sufficient to meet their needs. American Medicinal Spirits became National

Distillers, and they built a nifty new distillery out at Dundalk to handle Mount

Vernon, Baltimore Pure Rye, and any other of their newly-acquired brands they

chose to produce.

Of

course the end of prohibition meant the return of that popular brand to full

production capacity, which meant that the little distillery would no longer be

sufficient to meet their needs. American Medicinal Spirits became National

Distillers, and they built a nifty new distillery out at Dundalk to handle Mount

Vernon, Baltimore Pure Rye, and any other of their newly-acquired brands they

chose to produce.

And that means, of course, that Mount Vernon Pure Rye will be made here on the corner of Russell and Ostend streets...

Snap! John shoots his definitive picture, throws the car in gear, [and fastens his safety belt and checks his rearview mirrors LL] and with all four cylinders screaming out for more pedal, [looks both ways and LL] blasts out from under Russell Street and across two currently unoccupied lanes of opposing one-way streets on his way to our next destination. [Ahem! No Comment! Just wait 'til you get home, buster! LL]

(Yes, darling, even though you couldn't make it this time, I

feel as if you're with me every minute).

Mt. Vernon - Baltimore's Cecil

Distillery: The Pretender

Just you wait, 'enry 'annis, just you

wait!

OUR NEXT ATTRACTION is at the location of a distillery

that has perhaps the shortest history we've ever encountered. Known as the Cecil Distillery,

it

was built in 1873, on the east side of 16th Street between Fleet and Foster. It

produced just one brand of whiskey. And that brand was invented to meet a

specific purpose: to displace and destroy the world's currently

best-selling Maryland rye whiskey, based on nothing more than clever marketing

and the power of consumer product confusion.

it

was built in 1873, on the east side of 16th Street between Fleet and Foster. It

produced just one brand of whiskey. And that brand was invented to meet a

specific purpose: to displace and destroy the world's currently

best-selling Maryland rye whiskey, based on nothing more than clever marketing

and the power of consumer product confusion.

It was operated for a while by the Wineke-Airey Company, but had

been converted to a beer brewery before George W decided to use it to beat a

Philadelphian and a couple N'Yawkahs over their heads. No. Not THAT George W.

-- Hold on; we'll get around to George in minute.

First

we've got to find this place.

First

we've got to find this place.

Well, as you might guess they don't call it 16th street any more.

No one remembers when they did; it's been Haven Street for a long time, now. And

on the east side of that street, between Fleet and Foster, is a building that is

much too new to have been any part of a distillery built that long ago. The

building, which is itself empty and abandoned, bears the sign BRUNING PAINTS.

Since that's a regional brand here (our friend Chris says they pronounce it

"burning paint" here) one can't really tell if this was a manufactory or a

retail store.

Whatever

it was, it certainly wasn't a distillery, although it could certainly have been

the office of a distillery. And the surrounding area, complete

with railroad tracks, presents two outlines, either of which depending on the

size of the plant, would be believable as the original location.

Whatever

it was, it certainly wasn't a distillery, although it could certainly have been

the office of a distillery. And the surrounding area, complete

with railroad tracks, presents two outlines, either of which depending on the

size of the plant, would be believable as the original location.

Okay, back to George (I know; he was always on your mind)...

The fun began when the Hannis Distilling Company made the decision to sell their Mount Vernon Rye

brand (just the brand itself, not their distilleries).

It seems there

were multiple organizations bidding, and the successful buyer was the Cook and

Bernheimer Company, a wholesaler in New York City. One of the unsuccessful bidders was

George W. Torrey, a liquor dealer from Boston who apparently felt personally

slighted, and vowed to get even (a trait common to George W's, perhaps?). He

bought out the Cecil distillery instead and began bottling his own brand, taking

it immediately into national marketing. His brand was "The Only Original and

Genuine Mt. Vernon Rye." If you've noticed the distinction between "Mount" and

"Mt." you are more observant than Mr. Torrey was expecting his potential customers

to be. The resulting advertising war, was highlighted by Cook & Bernheimer

shouting, "Square bottle!"; Torrey countering, "No! ROUND bottle!" Mt. Vernon

bragged that it was bottled-in-bond, a significant feature, as the assurance of

product quality was a very relevant issue in the whiskey industry at that time

(more on that later).

It seems there

were multiple organizations bidding, and the successful buyer was the Cook and

Bernheimer Company, a wholesaler in New York City. One of the unsuccessful bidders was

George W. Torrey, a liquor dealer from Boston who apparently felt personally

slighted, and vowed to get even (a trait common to George W's, perhaps?). He

bought out the Cecil distillery instead and began bottling his own brand, taking

it immediately into national marketing. His brand was "The Only Original and

Genuine Mt. Vernon Rye." If you've noticed the distinction between "Mount" and

"Mt." you are more observant than Mr. Torrey was expecting his potential customers

to be. The resulting advertising war, was highlighted by Cook & Bernheimer

shouting, "Square bottle!"; Torrey countering, "No! ROUND bottle!" Mt. Vernon

bragged that it was bottled-in-bond, a significant feature, as the assurance of

product quality was a very relevant issue in the whiskey industry at that time

(more on that later).

Mount Vernon was not, nor did it feel it needed to be,

boasting all those World's Fair gold medals. And although Torrey directed his

brand from Boston and Cook & Bernheimer theirs from New York City, both brands

were actually being produced in Baltimore, which added local competition to the

mix. East Baltimore had its Mt. Vernon Distillery on Haven Street (it was called

16th Street at the time); west Baltimore had its Mount Vernon Distillery at

Ostend and Russell (now the site of Baltimore's own sports areas). And of course

the campaigns also got as much mileage as it could out of the competitive

allegiance of their New York City and Boston customers, foreshadowing by nearly

a century the recent World Series. But, unlike the Series, New York's Cook &

Bernheimer, with their square bottle, ended up the survivor. The 1909 edition of

Bonfort's Wine and Spirit Circular lists only Hannis' Mount

Vernon.

Mount Vernon was not, nor did it feel it needed to be,

boasting all those World's Fair gold medals. And although Torrey directed his

brand from Boston and Cook & Bernheimer theirs from New York City, both brands

were actually being produced in Baltimore, which added local competition to the

mix. East Baltimore had its Mt. Vernon Distillery on Haven Street (it was called

16th Street at the time); west Baltimore had its Mount Vernon Distillery at

Ostend and Russell (now the site of Baltimore's own sports areas). And of course

the campaigns also got as much mileage as it could out of the competitive

allegiance of their New York City and Boston customers, foreshadowing by nearly

a century the recent World Series. But, unlike the Series, New York's Cook &

Bernheimer, with their square bottle, ended up the survivor. The 1909 edition of

Bonfort's Wine and Spirit Circular lists only Hannis' Mount

Vernon.

Mount Vernon -

National Distillers

The NEW Original Mount Vernon

Rye

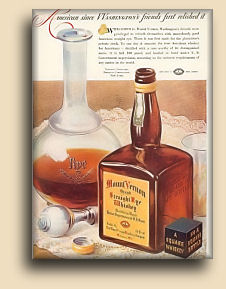

AFTER 1920, of course, neither would have been listed; there would (so it was believed) never again be a need for such a journal as Bonfort's. Not that there was no distilling of alcohol being done, even legal distilling. Pharmacies were allowed to sell whiskey for medicinal purposes (alcohol was considered a legitimate medicine at that time), and there were a handful of distilleries licensed to distill quantities as needed to refresh that supply. Hannis Distillers may have been one of those; if so it would account for the off-and-on distilling that may have prompted an occasional redirection of slaughterhouse-bound livestock past the distillery site. Mount Vernon Rye medicinal sales were handled through American Medicinal Spirits, and in 1928 they purchased the brand. The following year, National Distillers Products Corporation, headed by Seton Porter took over the AMS-controlled brands, and by the end of prohibition Mount Vernon Rye was one of their featured products.

Or at least the right to sell something called Mount Vernon

belonged to National Distillers.

Their

early post-repeal advertising played heavily (some might even say fraudulently)

on the Mount Vernon name, implying a direct connection between the brand and

whiskey reputed to have been made by the first president at his Mount Vernon

estate in Virginia (there was never such a connection, nor had Hannis Distilling

Company ever claimed one). Moreover, although National

Distillers did indeed own the Hannis #1 Mount Vernon distillery on Ostend and

Russell streets, at least until they sold it in 1953, the end of prohibition

found them owning over fifty percent of all existing American whiskey. Much of it ended up in various brands of blended whiskey; National Distillers themselves marketed only straight whiskey and

were proud of the few brands they featured -- including Mount Vernon. But when it came time to bottle (be it Mount Vernon, or Old

Overholt, Old Crow, Old Taylor, Bourbon DeLuxe, etc) they were not reluctant to

draw upon whatever of their wide-spread sources of straight whiskey was most

expedient.

Their

early post-repeal advertising played heavily (some might even say fraudulently)

on the Mount Vernon name, implying a direct connection between the brand and

whiskey reputed to have been made by the first president at his Mount Vernon

estate in Virginia (there was never such a connection, nor had Hannis Distilling

Company ever claimed one). Moreover, although National

Distillers did indeed own the Hannis #1 Mount Vernon distillery on Ostend and

Russell streets, at least until they sold it in 1953, the end of prohibition

found them owning over fifty percent of all existing American whiskey. Much of it ended up in various brands of blended whiskey; National Distillers themselves marketed only straight whiskey and

were proud of the few brands they featured -- including Mount Vernon. But when it came time to bottle (be it Mount Vernon, or Old

Overholt, Old Crow, Old Taylor, Bourbon DeLuxe, etc) they were not reluctant to

draw upon whatever of their wide-spread sources of straight whiskey was most

expedient.

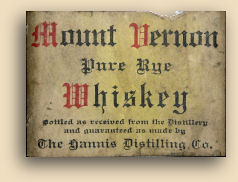

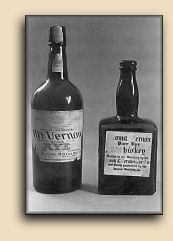

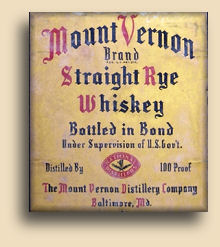

Other than the name, there is practically nothing in common

between the

Mount

Vernon Pure Rye Whiskey produced prior to 1920 by the Hannis distillery on the

left and the Mount Vernon Straight Rye sold by National Distillers from 1933 to

about the mid-'50s -- except the flavor! Even the

bottle is not identical. Notice the neck taper is different, as are the

shoulders. Notice also that neither is labeled as "Maryland Whiskey".

Mount

Vernon Pure Rye Whiskey produced prior to 1920 by the Hannis distillery on the

left and the Mount Vernon Straight Rye sold by National Distillers from 1933 to

about the mid-'50s -- except the flavor! Even the

bottle is not identical. Notice the neck taper is different, as are the

shoulders. Notice also that neither is labeled as "Maryland Whiskey".

That said, we have tasted Mount Vernon Rye whiskey made and bottled before prohibition by the Hannis Company, and Mount Vernon from National Distillers from the late 1930s, and we find them to be virtually identical (and really really delicious).

There is (or was -- only ruins remain today) a distillery on Sollers Point Road in Dundalk that is often referred to as having once belonged to National Distillers, but which is known to most local people as the Seagram's distillery, since they owned it for most of its time. It was originally built as the Baltimore Pure Rye distillery, and the smokestack with that name embedded in the bricks still remains. We know the Baltimore Pure Rye Distilling Company, of Dundalk, Maryland, existed as early as 1934 and lasted at least beyond 1944. But we also know that last July (2005), Louis A. Herstein of Baltimore died at the age of 94, and a Baltimore Sun obituary pointed out that after repeal he'd "worked for National Distillers Products and oversaw the building of the Baltimore Pure Rye distillery in Dundalk." Although that would imply that National Distillers built the Sollers Point distillery, we be more inclined to believe National might have purchased the existing BPR distillery in the mid- to late '40s. If that's the case, then possibly some of the Mount Vernon rye from later years might have been produced here, but we've seen nothing that would confirm that.

You can read more about the Dundalk distillery and our visit to its ruins under Baltimore Pure Rye.