American Whiskey

Distilleries of Eastern

Pennsylvania

June 16, 2006

|

|

"OH, PUBLICKER? Y'mean dah one down in Sowt Philly?

Yeh, I remember it.

'At was the whiskey distillery that made the Superfund Hazardous

Materials list"

"Yo! I sure whun'tah wanted ta drink any o' THAT whiskey!!"

Heh-heh! Yuck-yuck!

Wrong, CheeseSteak-breath.

Y'see, you're just used to the idea that someone operating a distillery is only

doing that in order to make beverage alcohol. But that's not always so.

Publicker's main business was as an industrial chemical plant.

A very large industrial chemical plant.

And even though they made a LOT of whiskey, that was only a small part of their operation. The whiskey-making part, Continental Distilling, folded up in the early '80s along with the rest of the company, but that didn't have anything to do with the hazardous conditions at the South Philadelphia alcohol refinery. Actually, Continental is still around, but it's an industrial distillery and food processing equipment dealer now. Publicker is still around, too, although they changed their name to PubliCARD in 1998 and went into the smartcard business. Apparently they're not doing so hot with that, either. According to their own investor relations page they don't expect to be around past the third quarter of 2006. And, at 3.5 cents a share, they don't expect there to be any funds remaining to distribute to shareholders. either. Which is pretty much what they tried to do to Philadelphia twenty years ago...

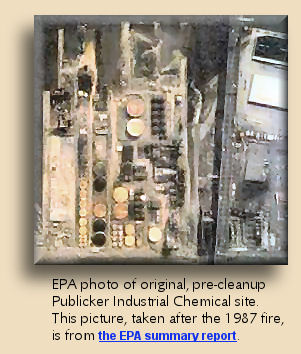

In June of 1987 a five-alarm fire broke out at a former Philadelphia chemical

plant. It wasn't the first time. It wasn't even the worst fire that site had

experienced.

But it was bad enough to have presented a threat of hazardous

wastes and dangerous materials that brought it to the attention of the Federal

Environment Protection Agency. And over the next ten years the former home of

the Publicker Industrial Chemical Company, now identified as CERCLA (superfund)

site #0303196, became known as one of the worst cleanups in the history of the

EPA (and PADER, the Pennsylvania Department of Environment Resources).

But it was bad enough to have presented a threat of hazardous

wastes and dangerous materials that brought it to the attention of the Federal

Environment Protection Agency. And over the next ten years the former home of

the Publicker Industrial Chemical Company, now identified as CERCLA (superfund)

site #0303196, became known as one of the worst cleanups in the history of the

EPA (and PADER, the Pennsylvania Department of Environment Resources).

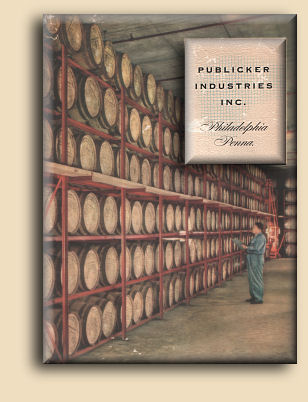

Publicker Industries, Inc., whose offices were (and still are) in West

Greenwich, Connecticut, began with Mr. Harry Publicker, who started off steaming

old whiskey barrels and extracting from them the gallon or two of whiskey that

had soaked into the charred wood. This he sold, and when the government tried to

prosecute him for not paying the revenue tax on the whiskey, he became highly

indignant. Obviously the tax had already been paid — it was paid by the man who

let the whiskey soak into the barrel. Anyway, that is how Harry Publicker passed

from the barrel business to the alcohol business. In 1912 he built and operated

a distillery on the Philadelphia riverfront between Bigler Street and Packer

Avenue. His company produced whiskey and industrial alcohol products there until

1985.

During prohibition Publicker concentrated on producing non-beverage alcohol and

industrial chemicals, and became very successful. How successful, you ask? Well,

in the early '20s Publicker was fermenting and distilling potatoes, molasses,

corn, and various grains into some six million gallons of industrial alcohol a

year. The company increased its capacity to sixty million gallons a year before

federal regulations tightened the industry allocation to a total of 70.5 million

gallons at the end of prohibition, of which Publicker produced a whopping 17 per

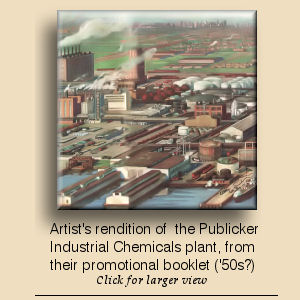

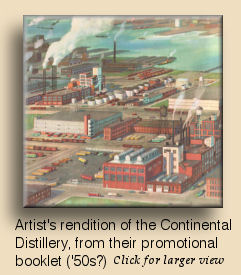

cent. By the mid-1950s the 40-acre plant at Packer and Delaware Avenue (which is now

called Christopher Columbus Blvd) had developed into one of the largest distilleries in the

world, specializing in products such as solvents, cleansers, antifreeze,

denatured alcohols, butyl acetate, ethyl acetate, acetone, dry ice and liquid

carbon dioxide, proprietary solvents, and refined fusel oil, among others. Not

to mention tons of high-quality livestock feed produced from the nutrient-rich

waste materials. The physical complex was comprised of twenty separate

buildings, 35 huge storage tanks, over 400 railroad cars and tankers. It was

serviced by the Pennsylvania, Baltimore & Ohio, and Reading railroads. Through

their subsidiary company, PACO, they operated a fleet of ten large ocean-going

tanker ships.

The company increased its capacity to sixty million gallons a year before

federal regulations tightened the industry allocation to a total of 70.5 million

gallons at the end of prohibition, of which Publicker produced a whopping 17 per

cent. By the mid-1950s the 40-acre plant at Packer and Delaware Avenue (which is now

called Christopher Columbus Blvd) had developed into one of the largest distilleries in the

world, specializing in products such as solvents, cleansers, antifreeze,

denatured alcohols, butyl acetate, ethyl acetate, acetone, dry ice and liquid

carbon dioxide, proprietary solvents, and refined fusel oil, among others. Not

to mention tons of high-quality livestock feed produced from the nutrient-rich

waste materials. The physical complex was comprised of twenty separate

buildings, 35 huge storage tanks, over 400 railroad cars and tankers. It was

serviced by the Pennsylvania, Baltimore & Ohio, and Reading railroads. Through

their subsidiary company, PACO, they operated a fleet of ten large ocean-going

tanker ships.

And after prohibition was repealed it was only natural for them to apply that

leverage of scale and their modern technologies to the production of potable

spirits.

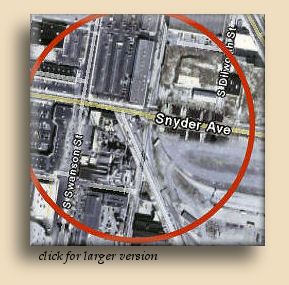

In August of 1933 they formed a subsidiary company, Continental

Distilling Corporation, and spent what would be over $27 million 2006 dollars

today to remodel their smaller distillery a few blocks north at the corner of

Snyder Street and Swanson Avenue. They filed the trademark on November 22, 1933

for their first brand, Charter Oak, which they registered for use with bourbon,

rye, rum, gin, brandy, and cordials. The Continental plant was especially

well-suited for producing blended whiskey and other spirit liquors, although

straight whiskey may have also been made there. They also produced gin and rum.

Some of their "manufactured" brands were Philadelphia, Diplomat, Cobb's Creek,

and Embassy Club whiskeys. Other early Continental brands were Haller's,

Linfield, and Old Hickory bourbons, as well as Rittenhouse and

Keystone State rye whiskeys. These were premium, aged whiskeys which may have been produced at

their more conventional distillery, Kinsey, about 35 miles up the Schuylkill

River in Linfield.

In August of 1933 they formed a subsidiary company, Continental

Distilling Corporation, and spent what would be over $27 million 2006 dollars

today to remodel their smaller distillery a few blocks north at the corner of

Snyder Street and Swanson Avenue. They filed the trademark on November 22, 1933

for their first brand, Charter Oak, which they registered for use with bourbon,

rye, rum, gin, brandy, and cordials. The Continental plant was especially

well-suited for producing blended whiskey and other spirit liquors, although

straight whiskey may have also been made there. They also produced gin and rum.

Some of their "manufactured" brands were Philadelphia, Diplomat, Cobb's Creek,

and Embassy Club whiskeys. Other early Continental brands were Haller's,

Linfield, and Old Hickory bourbons, as well as Rittenhouse and

Keystone State rye whiskeys. These were premium, aged whiskeys which may have been produced at

their more conventional distillery, Kinsey, about 35 miles up the Schuylkill

River in Linfield. However,

Publicker's own promotional description of that

facility -- also known as the Angelo Myers Distillery before prohibition -- focuses

entirely on the modern warehousing available there and proudly offers that its

fine whiskeys are aged there. But it only talks about aging. The promotional material never mentions

a word about distilling whiskey there

at all.

However,

Publicker's own promotional description of that

facility -- also known as the Angelo Myers Distillery before prohibition -- focuses

entirely on the modern warehousing available there and proudly offers that its

fine whiskeys are aged there. But it only talks about aging. The promotional material never mentions

a word about distilling whiskey there

at all.

Their success was probably at least partially due to a production technique that

their chemist, Dr. Carl Haner, developed. The way it was explained to a writer

for Fortune Magazine in 1934 is that, as every gentleman of the Old South knows,

if you put a keg of moonshine in the river it will age faster. Reason:

agitation. And if you put it near the stove it will age faster. Reason: heat.

Dr. Haner claimed to have devised a method of producing seventeen-year-old

whiskey in twenty-four hours. The Fortune writer thought that was a unique and

brilliant idea. Well, it may be brilliant, but it was hardly unique. That's the

same way most Maryland-style (and east Pennsylvania-style) whiskey was made

before prohibition, so it's hardly surprising that someone would revive the

method afterward. Of course, during the first few years after the end of

prohibition, when there was virtually no aged whiskey available, that would have

provided a very strong advantage.

It was probably phased out as existing stocks

aged conventionally. By the forties, Publicker was most likely using those

techniques only with blended whiskey, as is still being done today.

It was probably phased out as existing stocks

aged conventionally. By the forties, Publicker was most likely using those

techniques only with blended whiskey, as is still being done today.

They were also making bulk and made-to-order whiskey for other companies, and

providing bottling services (essentially the same thing) for others. Our friend,

and amateur authority on western Pennsylvania distilling, Sam Komlenic is

convinced that Publicker had close ties with the East Penn Distillery which,

despite its name, was located in the 23rd District of Pennsylvania -- that would

be Pittsburgh and Monongahela. During prohibition, American Medicinal Spirits

used East Penn product to fill bottles they labeled and sold as Spring Garden (Maryland) Rye and I.W. Harper (Kentucky) Bourbon.

Labeling required by the federally bonded

warehouses during that time made it necessary to state the true origins of

liquor on the back label, but as soon as prohibition ended and it was no longer

necessary to conform to bottled-in-bond regulations, many brands were bottled

tax-paid and that information

was no longer made available.

Sam also has documents indicating connections

between Publicker/Continental and other western Pennsylvania distilleries.

Labeling required by the federally bonded

warehouses during that time made it necessary to state the true origins of

liquor on the back label, but as soon as prohibition ended and it was no longer

necessary to conform to bottled-in-bond regulations, many brands were bottled

tax-paid and that information

was no longer made available.

Sam also has documents indicating connections

between Publicker/Continental and other western Pennsylvania distilleries.

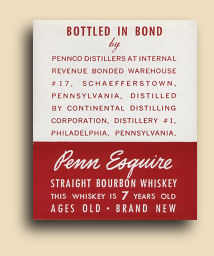

And we have the Penn Esquire label shown here that clearly shows their working relationship with

the Pennco distillery of Schaefferstown (#17), a distillery most people would

better recognize as Michter's.

They were probably also the suppliers of rye whiskey to Merle's Standard Distillers

in Baltimore, for bottling Pikesville "Maryland-Style" Rye after their regular

provider, Majestic Distilling in Lansdown, Maryland, ceased production in the

early seventies. Heaven Hill, the Bardstown, Kentucky company that purchased the

Pikesville brand in the early eighties also bought the Rittenhouse brand at

around the same time -- and they bought it from Publicker/Continental.

Pikesville brand in the early eighties also bought the Rittenhouse brand at

around the same time -- and they bought it from Publicker/Continental.

In June 2006 we visited the area where the Continental Distilling Corporation

once stood, where Weccacoe and Swanson Streets meet Snyder AvenueOf course it's not there anymore.

Or at least most of it. In fact, the buildings that

replaced it are in the process of being torn down themselves. There are remnants

of industrial distillery/refinery equipment that MIGHT have been part of a plant operating

less than thirty years ago. The most likely examples are now part of a plant

operated by Inolex. We took some photos of what's around here now.

We were

standing in the Wal-Mart parking lot; if Inolex isn't the location it's entirely

possible that the Wal-Mart was it.

We were

standing in the Wal-Mart parking lot; if Inolex isn't the location it's entirely

possible that the Wal-Mart was it.

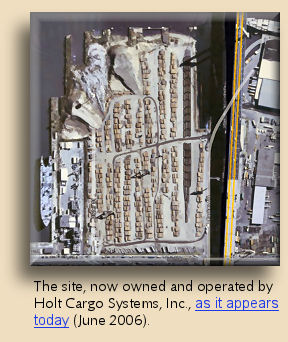

As you might guess, there is absolutely nothing to photograph at the site of the industrial chemical plant. The area itself has been stripped to the ground (and below) and is now being used to store countless stacks of... something. We can't get close enough to determine what.

A lot more interesting (at least to John, who

actually remembers when this ship sailed the ocean) is the SS United States moored to a pier just

north of the site. In the days when

John was making model airplanes and ships

(and reading "A Night To Remember" as required for school) "The Big U"

held the record as

the fastest ocean liner in the world, and America's most luxurious. It was the Concorde

of its day, and Presidents

and Queens and Premiers and Movie Stars and such sailed aboard her. Maybe even

Jackie Kennedy! And here she

is, tied up to Pier 82, faded and rusty but still sharp-looking. The current

owners are hoping to scare up enough money to bring her back to service as a

cruise ship.

John was making model airplanes and ships

(and reading "A Night To Remember" as required for school) "The Big U"

held the record as

the fastest ocean liner in the world, and America's most luxurious. It was the Concorde

of its day, and Presidents

and Queens and Premiers and Movie Stars and such sailed aboard her. Maybe even

Jackie Kennedy! And here she

is, tied up to Pier 82, faded and rusty but still sharp-looking. The current

owners are hoping to scare up enough money to bring her back to service as a

cruise ship.

I sure hope they can.

She was a fine old ship, and I'd hate to see her just fade slowly away, until

some kind of dramatic

emergency causes her to be rendered into salvage.

Perhaps even hazardous salvage.

There used to be a distillery like that around here. Used to be right over there...

BUT ALL THAT LIQUOR wasn't really the main focus of Publicker Industries.

It was only a contributing factor. The company's real success was the industrial

chemical plant down by the Walt Whitman bridge. Production there peaked during

World War II and when they became a publicly-traded corporation in 1946 they

were employing over 5,000 people worldwide. And then in the early 1950s

something went terribly wrong. Publicker began a remarkable decline that spanned

four decades. In 1986, the company, now consisting of less than 300 employees,

ceased operations and sold the property to the Overland Corporation, a wrecking

company, for about the price of a small motel.

In the late '70s Publicker began making some of its huge tanks, which were

standing empty and idle, available to other companies for storing fuel oils. They added other processing that they performed under contract for various

chemical and fuel companies. One gets the impression that they might not always

have obtained licensing for these deals; it's possible they were less careful

about environmental impact studies than they might have been.

They added other processing that they performed under contract for various

chemical and fuel companies. One gets the impression that they might not always

have obtained licensing for these deals; it's possible they were less careful

about environmental impact studies than they might have been.

And then...

In June 1981 Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Resources (PADER) conducted a hazardous waste inspection and began issuing Notices of Violation.

Publicker Industries was requested to develop a Preparedness, Prevention and Contingency (PPL) Plan.In January 1983, another hazardous waste inspection was done by PADER, and issued notices of violation for lack of records for quantity, description, and disposition of solid wastes, and improper disposal of laboratory wastes. PADER also classifies the facility as a small quantity generator.

In October 1985 PADER conducted another hazardous waste inspection and issued notice of violation for storage of more than 100 30 and 55 gallon drums with unknown contents, and a leaking 20,000 gallon tank, contents also unknown. Off-specification alcohol incineration was also stopped and notification of waste transport and disposal was required.

PADER also conducted a water quality management inspection which resulted in notices of violation for various spills, including heavy oil and antifreeze or dye.In March 1986 Dames & Moore, an environmental consulting firm, began a preliminary environmental evaluation of the Site for the Cuyahoga Wrecking Corporation, the parent of Overland Corporation.

In June 1986 the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) filed a complaint against Publicker Industries for operating a hazardous waste facility at the Site without a permit; storing ignitable waste on-site from June 9, 1983 to October 31, 1985; and shipping hazardous waste to Allied Petroleum in Norfolk, Virginia In October 1985.

In July 1986 PADER conducted yet another hazardous waste inspection and issued a further notice of violation for on-site storage of drums, many of which were corroded and leaking, and PCB oils in building transformers.

Publicker contended that they contracted Cuyahoga to remove the drums in question.In October 1986, PADER obtained a judgment requiring Overland Corporation and Cuyahoga Wrecking Corporation to submit a proposal for removal and disposal of wastes.

In November 1986, two Cuyahoga Wrecking Corporation demolition workers were killed during an explosion while cutting a pipeline containing residual ignitable material.

Shortly thereafter, Overland Corporation and Cuyahoga Wrecking Corporation

declared bankruptcy and abandoned the site.

Shortly thereafter, Overland Corporation and Cuyahoga Wrecking Corporation

declared bankruptcy and abandoned the site.

In June 1987 PADER conducted a preliminary assessment of the site, discovering large amounts of asbestos from pipe insulation, and large amounts of solids, sludges, and liquids of unknown types in rail tank cars, tank trucks, and storage vessels.

And then there was the fire mentioned earlier. Destroying the carbon dioxide utilization area and one of the piers, it burned for two hours, during which muffled explosions and fire flares were observed. Federal EPA officials don't like fire flares. They particularly don't like muffled explosions.In July 1987 the Federal EPA conducted their own inspection, finding numerous spill areas, improper drum storage,

a leaking process line, an

oily sheen emanating from the site into the Delaware River, and shock sensitive

and explosive materials throughout.

a leaking process line, an

oily sheen emanating from the site into the Delaware River, and shock sensitive

and explosive materials throughout.

The NPL Site Narrative Report cites over 400 tanks, rail cars, and tank cars holding approximately two million gallons of hazardous materials; approximately 1,200 drums; four chemical laboratories with an estimated 7,000 containers of known content (including acids, explosive compounds, and flammable compounds) and 5,000 containers of unknown content; 180 cylinders holding toxic, flammable, and reactive gases; 150 pieces of electrical equipment, some containing PCBs; several hundred miles of aboveground and underground transfer lines, some covered with asbestos; reaction vessels; production buildings; and two power houses. In addition, they that most of the vessels and transfer lines apparently held hazardous materials and were either actively leaking or in disrepair due to neglect or vandalism.

Other than that, though, the place appeared to be just fine...In September 1987 EPA filed a consent agreement and order under Section 106 CERCLA against Publicker Industries, Inc.. Under the order, Publicker Industries agreed to hire an outside firm to perform a Site assessment.

In December 1987 EPA conducted another site inspection and declared the site a threat to human health and the environment.

Cleanup was

begun immediately, using CERCLA emergency funds, and continued for a full year.

Cleanup was

begun immediately, using CERCLA emergency funds, and continued for a full year.

However, a detailed Site Inspection by PADER taken during the summer of 1988 showed that the soil and groundwater were also hopelessly contaminated.In May 1989 the site scored a 59.99 on the EPA's Hazard Ranking scale, which earned it the honor of a place on the Hazardous Site National Priority List (NPL).

The cleanup and inspections and further cleanup, etc. continued until the site was finally pronounced completed and removed from the Superfund National Priorities List of most hazardous toxic waste sites. That was in November 2000, fourteen years and around twenty million dollars after Publicker Industries, Inc. had already washed their hands of the alcohol-distilling business and left Philadelphia to wallow in its wake.

And for more -- MUCH more -- about the

Publicker/Continental distillery...

Dave Ziegler, a fine gentleman who worked for many years at Publicker's Kinsey

facility in Linfield, has become an amateur historian and one-man museum of lore

and memorabilia from these distilleries. As a frequent contributor to

www.bourbonenthusiast.com and

other sites, Dave provides an overwhelming wealth of detail and reminiscences

that will make you feel as if you'd worked there all your own life, too. We

had the unique and very enjoyable pleasure of spending part of an afternoon with

Dave in the summer of 2009.

And now (as of 2015) one of

Publicker/Continental's key brands of whiskey

is once again available and being made in Philadelphia

See our page on the Millstone Spirits Group and the

New Liberty distillery!