American Whiskey

September 4, 2015 |

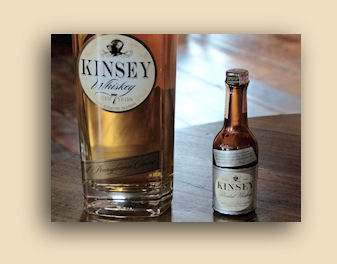

This is the NEW Kinsey whiskey, distilled by the New Liberty distillery.

For a look at the original Kinsey whiskey, as produced by the

Continental Distilling branch of the Publicker company,

you might also want to check here and here

![]()

Not just by obtaining a brand label and bottling bulk whiskey under it, no sir.

Not even by trying to reproduce the kind of spirit the original used to be.

No,

the distillers at the New Liberty Distilling Company have made it their

objective to produce an upgraded and better version of what was once a

very popular (gulp! dare we suggest?) blended American whiskey.

No,

the distillers at the New Liberty Distilling Company have made it their

objective to produce an upgraded and better version of what was once a

very popular (gulp! dare we suggest?) blended American whiskey.

Okay, now that we've tweaked your curiosity, and the bourbonistas have left screaming from the page, running back to their monthly ratings charts, let's get to the bottom of how one creates a silk purse from a sow's ear. Or in this case, how to create a brand of real whiskey that emphasizes the good qualities that once defined its blended namesake. How... and why.

The story begins with a spirit craftsman who was no stranger to the art of distilling. Robert Cassel was one of the founders of Philadelphia Distilling back in 2006, the year when Linda and John were visiting the Linfield and Publicker distillery sites. He had been brewer at Harpoon Brewing in New England and at Victory Brewing in Philadelphia, and Philadelphia Distilling went on to produce award-winning Bluecoat Gin and Vieux Carré Absinthe while he was there.

They still do, but more recently Rob formed a partnership, the Millstone Spirits Group, with such industry luminaries as major brand developer Charlie Andrews and Thomas Jensen, former sales manager at Allied Domecq and president/CEO of Remy Cointreau. Their mission was to develop a brand of Philadelphia whiskey that would compete well in a marketplace of new craft/artisan whiskies. Rob Cassel's mission has been to create that whiskey.

One problem with that mission is that

the brand they obtained rights to, and which represents a big part of

Philadelphia's post-Prohibition spirits tradition, was Kinsey. Now the Kinsey

brand extends way back. It was originally distilled in the early 1900s at a

distillery in Linfield, about an hour or so up the Schuylkill river from

Philadelphia (at today's expressway speeds). Or at least it was made from such

whiskey, perhaps along with spirits from other sources.

The brand was owned and

marketed by the A. & H. Myers Distilling Company, Inc., Angelo J. Myers,

President, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The original Kinsey whiskey was straight

bourbon and rye. Even after Prohibition and up to around 1950 the Linfield

distillery was shipping bottled-in-bond straight bourbon whiskey under the brand

name of Haller's County Fair and others. The distillery was owned and operated

by the Publicker Distilling Company's Continental Distilling division, which was

responsible for their beverage spirits. Publicker itself was perhaps America's

largest industrial alcohol products distiller. Both were located in

Philadelphia. Continental had purchased the Linfield distillery shortly after

Prohibition and used it as a source for both straight whiskies and flavoring

whiskey to be used in making their blended products.

The brand was owned and

marketed by the A. & H. Myers Distilling Company, Inc., Angelo J. Myers,

President, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The original Kinsey whiskey was straight

bourbon and rye. Even after Prohibition and up to around 1950 the Linfield

distillery was shipping bottled-in-bond straight bourbon whiskey under the brand

name of Haller's County Fair and others. The distillery was owned and operated

by the Publicker Distilling Company's Continental Distilling division, which was

responsible for their beverage spirits. Publicker itself was perhaps America's

largest industrial alcohol products distiller. Both were located in

Philadelphia. Continental had purchased the Linfield distillery shortly after

Prohibition and used it as a source for both straight whiskies and flavoring

whiskey to be used in making their blended products.

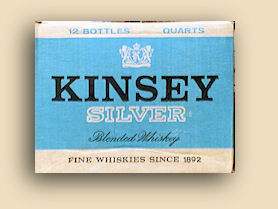

And the Kinsey brand was a blended whiskey.

Blended whiskies were quite popular

in America at the time. The fine, richly-flavored bourbons and ryes we enjoy

today only became universally popular in America in the late 1980s, at about the

same time that super-premium expressions were coming into high demand in Japan.

Most Americans who drank whiskey -- and that was a minority of drinkers --

preferred either blended American whiskey or Canadian, which is very similar.

Both are distinguished by very light taste with little depth, although the

better premium Canadian whiskies can have surprisingly, if subtle, fine flavor

variations. Basic American blended whiskey, such as Seagram's 7, Beam's

Eight-Star, Kessler, and -- until distiller Jim Rutledge's successful petition

to bring back straight whiskey -- Four Roses, ruled the market from the repeal

of Prohibition all up through the '60s and '70s. Among those was Kinsey. But

that isn't the case today. Today the blended American whiskey brands occupy the

very bottom shelf of the liquor store, not at all like blended Scotch, some of

which are very desirable and sought-after (and priced accordingly).

Most Americans who drank whiskey -- and that was a minority of drinkers --

preferred either blended American whiskey or Canadian, which is very similar.

Both are distinguished by very light taste with little depth, although the

better premium Canadian whiskies can have surprisingly, if subtle, fine flavor

variations. Basic American blended whiskey, such as Seagram's 7, Beam's

Eight-Star, Kessler, and -- until distiller Jim Rutledge's successful petition

to bring back straight whiskey -- Four Roses, ruled the market from the repeal

of Prohibition all up through the '60s and '70s. Among those was Kinsey. But

that isn't the case today. Today the blended American whiskey brands occupy the

very bottom shelf of the liquor store, not at all like blended Scotch, some of

which are very desirable and sought-after (and priced accordingly).

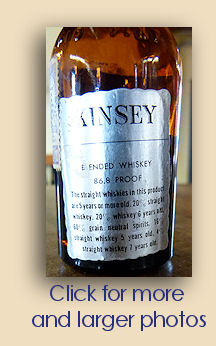

Why is this? Mainly because, unlike Scotch or even Canadian whiskies, American blends are made from only a small amount of properly-aged whiskey, ranging from about 20% to 35%, dissolved in 190° proof industrial ethanol, and bottled on the spot. Essentially whiskey-flavored vodka. Kinsey was, as a matter of fact, at the lower end of that range.

And why

would an artisan distiller, a craftsman of mashing, fermenting, distilling, and

aging fine spirits, and a marketer and brand-developer of some of the most

highly-respected spirits in the world want to reproduce such a product?

Because they knew they could do it better.

They knew

they could produce a whiskey that captured the spirit (in a literal sense) of

the old Kinsey whiskey whose brand they now owned, and produce it in a way that

had the flavor that a blended whiskey COULD have. They could do this by

obtaining 100% corn light whiskey. Unlike regular whiskey, which cannot

be distilled at a higher proof than 160° (and which, therefore, retains more of

the flavor of the grains it is made from), and which is typically distilled at

far lower than that (mostly around 140° and sometimes as low as 115°), light

whiskey is distilled at 180° proof, making it only a little more flavorful than

vodka (190°). But the difference is significant. And then this light whiskey is

aged for 7 years or more in used barrels, which is typical of the kind of grain

spirits used in the finest of Canadian and Scotch whiskies. The Kinsey 7 brand

is 100% this type of whiskey; there is no grain neutral spirit used. The

resulting product tastes less like an American blend than it does good Canadian

whisky.

Which it may be. They don't say where their whiskey is distilled, other than that there are multiple sources. Aged 100% corn whiskey isn't commonly found on retail shelves, but it is an important flavoring element in other blends. MGP Industries in Indiana and a number of Canadian distillers produce such whiskey.

The other

two expressions of the Kinsey brand are Rye and Bourbon, and each is equally

unique. Kinsey Rye whiskey is blended from multiple-sourced rye whiskies (but no

neutral spirits) and is offered at 86° proof.

In doing so, they seem to have achieved a flavor profile that is eerily similar

to other old Pennsylvania ryes, such as Continental's own Rittenhouse. Kinsey's

bourbon whiskey is even more unusual. Also a blending of sourced whiskey, the

bourbon is made from 51% corn, as required for bourbon, and 49% malted barley!

It is aged for two to three years.

In doing so, they seem to have achieved a flavor profile that is eerily similar

to other old Pennsylvania ryes, such as Continental's own Rittenhouse. Kinsey's

bourbon whiskey is even more unusual. Also a blending of sourced whiskey, the

bourbon is made from 51% corn, as required for bourbon, and 49% malted barley!

It is aged for two to three years.

New

Liberty, in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, is located in what was

once the Crane Building, a stable for delivery vehicles and draft horses.

Arriving at the site, one would never know from the construction turmoil going

on outside just what a beautiful restoration the Millstone folks have

accomplished inside. Part antique tradition, part urban-chic, the distillery

occupies three stories and uses all of them to full capacity. As you enter at

street level, you are immediately confronted with the heart of the operation,

Rob's still. As we visit today, Rob isn't here, but his assistant Dave Pié

(pee-uh) is quite capable of taking us through and answering all of our

questions. Now, the more astute of our readers may already be wondering, "just

what does a 'distillery' that produces only sourced whiskey need with an actual

still"? And the answer is, plenty.

The Kinsey line of products is what is being

created now, but spirits are being distilled here on a regular basis. The main

still itself is a beautiful creation of another of Millstone's companies,

Specific Mechanical Systems Ltd. It is a very innovative tool, consisting of a

240-gallon main

copper distilling section with a fitting that allows any of three (or more)

specially-designed top pieces to be easily fastened in place, making the same

still into a traditional pot still, a column still, an alcohol stripper, etc. The top

sections are lined up on a platform and can be exchanged via forklift in just

minutes. Right now the pot still head is in place, with the other two ready to

be installed as needed.

The Kinsey line of products is what is being

created now, but spirits are being distilled here on a regular basis. The main

still itself is a beautiful creation of another of Millstone's companies,

Specific Mechanical Systems Ltd. It is a very innovative tool, consisting of a

240-gallon main

copper distilling section with a fitting that allows any of three (or more)

specially-designed top pieces to be easily fastened in place, making the same

still into a traditional pot still, a column still, an alcohol stripper, etc. The top

sections are lined up on a platform and can be exchanged via forklift in just

minutes. Right now the pot still head is in place, with the other two ready to

be installed as needed.

Mostly what Rob and Dave are running

now is malt whiskey, and that is being aged in 53-gallon barrels.

When it has

matured enough to release it will probably be under the "New Liberty" label.

There is also another rye whiskey in the future, which may also be bottled as

"New Liberty". Or not. Other spirits that they have been experimenting

with are aging in smaller cooperage, some barrels as small as five gallons. And

where are all these barrels stored? That would be the second floor.

Really? Yup! There is an elevator in the back, which was once used to lift

horses to the stalls that were on the second floor of the building. They

refurbished the elevator and it is now used to (carefully) move newly-filled

barrels from the distillery floor, where they are stored in those very same

stalls that once held proud steeds. And to move the cartons of product that is

bottled on that floor down to awaiting transportation -- assuming any

transportation can negotiate the narrow roads under construction all around the

building at the moment.

When it has

matured enough to release it will probably be under the "New Liberty" label.

There is also another rye whiskey in the future, which may also be bottled as

"New Liberty". Or not. Other spirits that they have been experimenting

with are aging in smaller cooperage, some barrels as small as five gallons. And

where are all these barrels stored? That would be the second floor.

Really? Yup! There is an elevator in the back, which was once used to lift

horses to the stalls that were on the second floor of the building. They

refurbished the elevator and it is now used to (carefully) move newly-filled

barrels from the distillery floor, where they are stored in those very same

stalls that once held proud steeds. And to move the cartons of product that is

bottled on that floor down to awaiting transportation -- assuming any

transportation can negotiate the narrow roads under construction all around the

building at the moment.

The third floor is the office space... and the tasting room. And it is a beautiful tasting room, if somewhat minimalist. Before arriving there, we pass a landing that contains the restrooms. Nothing particularly remarkable about that, except that the men's room contains a photograph of President Bill Clinton, who visited the Crane building back in 2003 and (presumably) used the facility. Also left over from the building's past is a bizarre chandelier on the second floor that they felt ought to remain here. No one has any idea of why it was made.

Here we also meet Stephanie, who

keeps all the records and paperwork. Stephanie was our original contact when we

called to see if we could come and visit. We first learned of New Liberty from

our friend Dave Ziegler in Pottstown, Pennsylvania. Dave is the ultimate expert

and archivist for anything Kinsey. It is unlikely that anyone living either

knows more nor has more examples and objects from the Kinsey distillery in

Linfield than does Dave. His writings appear in several places on the internet;

One that we highly recommend is his

"My Days at Kinsey Distillery" topic

at

http://bourbonenthusiast.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=17&t=4923

Here we also meet Stephanie, who

keeps all the records and paperwork. Stephanie was our original contact when we

called to see if we could come and visit. We first learned of New Liberty from

our friend Dave Ziegler in Pottstown, Pennsylvania. Dave is the ultimate expert

and archivist for anything Kinsey. It is unlikely that anyone living either

knows more nor has more examples and objects from the Kinsey distillery in

Linfield than does Dave. His writings appear in several places on the internet;

One that we highly recommend is his

"My Days at Kinsey Distillery" topic

at

http://bourbonenthusiast.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=17&t=4923

|

|

|

Story copyright © 2015 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved.

|

|