American Whiskey

October 11, 2015

|

|

Chesapeake Bay pirates were known as Picaroons

![]()

Although "distilleries" that are really only bottling plants for existing whiskies, rums, vodkas, gins, tequilas, and so forth have continued to operate in Maryland, until quite recently no spirit has been actually distilled here (at least legally). Not since the early 1970s.

In

fact, it wasn't until 2005, when the

Fiore Winery people in Pylesville

were successful in lobbying the Maryland General Assembly to pass

legislation permitting distillery operations at wineries that any kind of

commercial spirit (grappa and brandy in their case) was distilled in the

state.

In

fact, it wasn't until 2005, when the

Fiore Winery people in Pylesville

were successful in lobbying the Maryland General Assembly to pass

legislation permitting distillery operations at wineries that any kind of

commercial spirit (grappa and brandy in their case) was distilled in the

state.Less than three years later, brothers Chris and Jon Cook established the Blackwater Distillery in Stevensville, a community on Kent Island in the middle of Chesapeake Bay. Like many startup distilleries looking to produce a saleable product they could be proud to offer as quickly as possible, Blackwater's first product was a high-end vodka, Sloop Betty. Like many brands of vodka, Sloop Betty is not distilled in-house, but unlike most of the others it is a carefully-selected blend of existing spirits, mainly a red winter wheat spirit that they source from a distiller in Italy and organic sugar cane distillate from Brazil. The result is a vodka that has won numerous awards and remains their flagship spirit.

The same sort of attention to detail and commitment to provide a unique expression of a spirit went into their next offering, and the one that concerns us most. In 2015, Blackwater released Picaroon Maryland Rum. Picaroon (which means "rogue" or "pirate") shares with Sloop Betty an authenticity that comes from a passionate attention to detail and historic accuracy. However, Picaroon rum differs from Sloop Betty vodka dramatically in that it is distilled entirely at the Blackwater distillery here in Maryland. It also differs in its attention to historic accuracy, in that it is not simply an American rum as might have been distilled in New England in the 1700s (although there is evidence that a handful of rum distilleries existed in Maryland, most rum found in Baltimore taverns was imported), but rather an American version of the type of rum that would have been available at that time. There were not one, but two, types of rum that arrived on the docks of Baltimore in the 18th and 19th centuries.

One

type, the more common one, originated in the British- and Spanish-speaking

islands of the Caribbean, as well as New England as a result of the

triangle slave trade. This was rum made from molasses, a by-product of

sugar production. The other type was rum that came from the French

Caribbean colonies, such as French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Haiti, and

Martinique. That rum was produced, not from molasses, but from raw sugar

cane juice, and it tasted quite differently from Jamaican, Cuban, or

Barbados rums.

One

type, the more common one, originated in the British- and Spanish-speaking

islands of the Caribbean, as well as New England as a result of the

triangle slave trade. This was rum made from molasses, a by-product of

sugar production. The other type was rum that came from the French

Caribbean colonies, such as French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Haiti, and

Martinique. That rum was produced, not from molasses, but from raw sugar

cane juice, and it tasted quite differently from Jamaican, Cuban, or

Barbados rums.

Nearly

all of the rum being produced by today's craft/artisan distillers is the

latter style; the only one we are aware of that is made exclusively in the

French tradition is Blackwater's Picaroon. They also ferment that sugar

juice with a strain of yeast from the island of Martinique and in a room

that is temperature-controlled to emulate Caribbean temperatures. And

that's the reason why we wanted to visit this innovative distillery.

Nearly

all of the rum being produced by today's craft/artisan distillers is the

latter style; the only one we are aware of that is made exclusively in the

French tradition is Blackwater's Picaroon. They also ferment that sugar

juice with a strain of yeast from the island of Martinique and in a room

that is temperature-controlled to emulate Caribbean temperatures. And

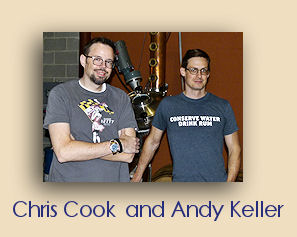

that's the reason why we wanted to visit this innovative distillery.And so we arrive at the non-descript modern industrial park location of Blackwater Distilling, in Stevensville, Maryland. We are greeted by Chris Cook who, along with his brother Jon, owns and operates the distillery, and Andy Keller, who is the distiller of Picaroon rum. Although surprised to see us, they are totally gracious hosts who drop whatever tasks they had intended to be doing and spend at least half an hour talking with us until their next scheduled tour (for which other people arrive while we are waiting). Chris is the CEO and, with his brother Jon, is the founder of the company. Andy is the distiller responsible for Picaroon and also for the blending of the spirits that constitute Sloop Betty vodka.

Our tour of the distillery is not complicated. Everything from the wash tubs for fermenting to the stills themselves (there are two, a 500- and a 100-gallon capacity; one for stripping, the other for doubling), to the barrel storage

(Blackwater

is also distilling and barreling Maryland rye whiskey for future release)

is contained within the same room. Most of the spirit is stored in large,

square food-grade plastic storage containers until it is either bottled or

transferred to wooden barrel storage. The wheat vodka from Italy and the

Cachaša from Brazil are stored in these containers, as is the

newly-distilled rum, which is, of course, clear and uncolored. The "gold"

type of Picaroon Rum is not aged but is colored (as are all "gold" rums)

with caramel (basically, burnt sugar). However, the caramel used to color

Picaroon Rum is made in-house to highly-controlled standards, not simply

commercial caramel. In fact, the caramel used is of such high quality that

Blackwater is considering production of the caramel itself for sale to

commercial users. The rum is filtered once; the vodka, twice. There will

also be true barrel-aged (a˝ejo) rum, a mixture of Picaroon rum that is

now aging in both new and used barrels.

(Blackwater

is also distilling and barreling Maryland rye whiskey for future release)

is contained within the same room. Most of the spirit is stored in large,

square food-grade plastic storage containers until it is either bottled or

transferred to wooden barrel storage. The wheat vodka from Italy and the

Cachaša from Brazil are stored in these containers, as is the

newly-distilled rum, which is, of course, clear and uncolored. The "gold"

type of Picaroon Rum is not aged but is colored (as are all "gold" rums)

with caramel (basically, burnt sugar). However, the caramel used to color

Picaroon Rum is made in-house to highly-controlled standards, not simply

commercial caramel. In fact, the caramel used is of such high quality that

Blackwater is considering production of the caramel itself for sale to

commercial users. The rum is filtered once; the vodka, twice. There will

also be true barrel-aged (a˝ejo) rum, a mixture of Picaroon rum that is

now aging in both new and used barrels. On this lovely October afternoon Andy guides us and another couple through the different spirits and how they're made. The other couple are not particularly familiar with spirits, their only experience with rum, albeit an excellent one, being Gosling's Black Seal from Bermuda. With Chris sitting in the background, Andy is able to help the other couple learn more about rum. When the time came for tasting, they were amazed at the differences, and we're sure they will go on to apply their curiosity to more expressions. They bought some Picaroon and so did we (of course).

The stills used to make Picaroon and Blackwater's future Maryland rye product were made by RockyPoint, and are quite unique.

Although

the working parts are all copper, they include decorative pieces made of

stainless steel, such as the lightning-bolt legs, and retro-sci-fi-looking

controls that look as if they'd be right at home in Willie Wonka's

chocolate factory or aboard Captain Nemo's Nautilus. Unfortunately for

other would-be distillers who would appreciate RockyPoint's skills,

according to Andy that

company is no longer in business. Also unique for rum stills are the

"plugs" of copper mesh, made by Sulzer, which are placed into the still

head to give even more copper exposure than normal reflux would provide.

The tradition of filling the heads of whiskey stills with copper artifacts

goes way back, but these mesh plugs are of a highly specialized design

specific to use in spirit stills.

Although

the working parts are all copper, they include decorative pieces made of

stainless steel, such as the lightning-bolt legs, and retro-sci-fi-looking

controls that look as if they'd be right at home in Willie Wonka's

chocolate factory or aboard Captain Nemo's Nautilus. Unfortunately for

other would-be distillers who would appreciate RockyPoint's skills,

according to Andy that

company is no longer in business. Also unique for rum stills are the

"plugs" of copper mesh, made by Sulzer, which are placed into the still

head to give even more copper exposure than normal reflux would provide.

The tradition of filling the heads of whiskey stills with copper artifacts

goes way back, but these mesh plugs are of a highly specialized design

specific to use in spirit stills.The new spirit that Blackwater has begun distilling and aging is Maryland rye whiskey, the second of its type in forty-some years (after Lyon Distilling, which began in 2013). Unlike Lyon, however, Blackwater is aging their whiskey in standard-size 53-gallon oak barrels and so it will be several years before it has matured enough for release.

So today, while Blackwater's Maryland rye whiskey and a˝ejo rum sit patiently in their oaken barrels, we must be content with the unique experience of Picaroon white and gold rum, which is certainly a treat in its own right. We can hardly wait until Blackwater's Maryland Rye is available.

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2015 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|