American

Spirits

American Rum

![]()

THE MAIN MENU of this

website begins with "American whiskey, and how it got this way".

The first

article begins, "It wasn't always bourbon, you know...".

Which is

true; but really it wasn't always whiskey, either.

It was RUM

Rumbullion

Kill devil

The connection between England's North American colonies and their Caribbean colonies was vital to the survival of both. The earliest attempts to make a profit from the northern colonies were far less than successful; the first settlers were not particularly skilled and barely were able to survive, let alone provide profitable exports to their sponsors in Europe. The raw materials they had -- lumber, stone, etc. -- were already abundant in England. And attempts at manufactured goods -- glass, textiles -- were not encouraging. Tobacco was a hit, and hemp. Salt fish in the northern colonies.

By the end of the 17th century, the North

American colonies were

much more settled and successful. Even so, they were not

exactly the shining star of the British Empire. Pretty much the main reason for

England to maintain colonies in North America was for defense and imperial

purposes. Their Caribbean island colonies, on the other hand, were quite

profitable. Barbados, Antigua, and Jamaica were far

more valuable to England, primarily because of one product: sugar. Sugar is

made by boiling down the juice from crushed sugar cane and retrieving the

sugar in the form of crystals. The remaining sticky dark goo is called

molasses and is considered a waste product. The molasses itself can be

fermented and distilled into rum, which was done on most of the

islands. But that was not the case on the French islands. Rum was distilled

on Haiti, Martinique, Guadeloupe, and other French colonies, but only from

pure sugar cane juice, not molasses. And Frenchmen in Paris didn't drink it,

at least not legally.

The highly-placed merchants of Cognac and other

brandies successfully pressured the French government to make importation of

rum or molasses into France against the law. That meant that the French

planters, charged with an ever-increasing demand for finished sugar, had no

place to sell the byproducts, rum and molasses. As a way of compensating,

the French government tried to create a foreign market for molasses by

passing a law requiring that New England fish (for which the French islands

were a huge market) could only be paid for with molasses.

The highly-placed merchants of Cognac and other

brandies successfully pressured the French government to make importation of

rum or molasses into France against the law. That meant that the French

planters, charged with an ever-increasing demand for finished sugar, had no

place to sell the byproducts, rum and molasses. As a way of compensating,

the French government tried to create a foreign market for molasses by

passing a law requiring that New England fish (for which the French islands

were a huge market) could only be paid for with molasses.

North American colonists, of course, also had another incentive to trade with the French, rather than the British islands. They were desperately in need of a market for their grains and livestock, because British law forbade them from selling these to England, where they were produced in great abundance already. Much as in the case of France and their colonies' rum and molasses, the English Parliament wanted to eliminate any colonial competition to their own home-grown industries. Therefore French molasses was both cheaper and more abundant, although rum from the British islands was considered to be better. Of course, the British also wanted to restrict colonial purchases of French-made goods, too, but a thriving smuggling business developed, against which the English were never successful. Their attempts eventually became a cornerstone of the American Revolution. George Washington, as a young man long before his role in that revolution, lived for awhile in Barbados, accompanying his brother who was sent there to recuperate from tuberculosis. While there, the future Father of His Country apparently acquired a taste for Bajan rum. He is said to have demanded a barrel of it imported and served at his inaugural.

But long

before that the rum industry was already huge in New England. Massachusetts

and especially Rhode Island were the centers for an amazing number of rum

distilleries, sixty-something in Massachusetts, and over thirty in Rhode

Island by the mid 1760s, 22 of them in Newport alone. The reason for this

was the notorious Triangle Trade.

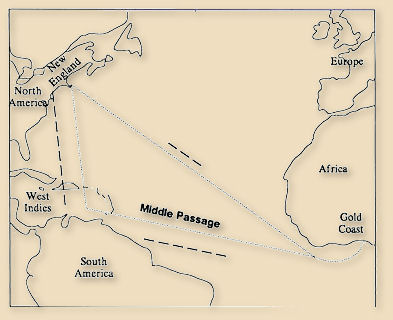

There

have been lots of so-called "triangle trades", basically a system of

shipping a product to a market to trade for a product needed by a second

market, and trading there for the raw materials needed by the original

manufacturers. The one we tend to speak of in Capital Letters is the one

associated with the West African slave trade. It was originally set up

between Europe, West Africa, and the Caribbean islands, and the medium of

exchange for slaves were mostly guns and ammunition. But the ready

availability of cheap molasses as raw material for rum created the more

familiar New England - Africa - West Indies route.

There

have been lots of so-called "triangle trades", basically a system of

shipping a product to a market to trade for a product needed by a second

market, and trading there for the raw materials needed by the original

manufacturers. The one we tend to speak of in Capital Letters is the one

associated with the West African slave trade. It was originally set up

between Europe, West Africa, and the Caribbean islands, and the medium of

exchange for slaves were mostly guns and ammunition. But the ready

availability of cheap molasses as raw material for rum created the more

familiar New England - Africa - West Indies route.

No

one knows, or ever will know, what New England rum tasted like. That is also

true of Monongahela and Bourbon whiskey. The generic roots of all three

extend deep into the misty past before there were bottles and labels and

such. If you are lucky enough to have experienced tasting whiskey made in

the 1930s through the '70s you will understand that whatever similarity they

might happen to share with brands using those names today is either

imaginary or completely accidental. A sampling of whiskies bearing names

such as "J. W. Dant" or "Old Taylor" today will provide not the slightest

clue as to what those brands of whiskeys tasted like forty years ago. The

same is true of "Old Fitzgerald" and "Old Crow". It's certainly true of

brands such as Beam's version of Old Overholt (which at least emulates the

National Distillers product of the late 1980s) or Heaven Hill's Pikesville

Rye, which isn't even close to what Baltimore's Majestic Distillers was

producing in the '60s.

And all of those whiskies were, themselves, only post-Repeal "imitations" of

fine old brands that had earned a reputation for excellence a half-century

earlier, in another era. But even those examples of Monongahela and Bourbon

weren't "The Real Thing". Like the later ones, they were just contemporary

brands using a familiar name to make themselves seem as though they were

revered products from their own past. Their origins date from a time when

there were no bottles or labels.

Spirits

were shipped and sold in barrels only. Absolutely everything about

distilling, about storage, transportation, marketing, and probably even

grain agriculture, has changed dramatically since then. Certainly the laws

affecting honesty in identifying such products have changed.

Spirits

were shipped and sold in barrels only. Absolutely everything about

distilling, about storage, transportation, marketing, and probably even

grain agriculture, has changed dramatically since then. Certainly the laws

affecting honesty in identifying such products have changed.

The last barrel of true New England rum was filled even further back than that. The triangle trade was dealt a mortal blow with the legal collapse of the slave trade in the late 1770s and its practical dissolution by about 1810. New England Rum has been an object of fantasy ever since, although whether that fantasy was about how wonderful it was or how horrible is open to discussion. A LOT of discussion. There are basically two completely opposite ideas of just what New England rum really was like. It all depends on just what one thinks of as New England rum.

The original New England rum was made from molasses imported from British Caribbean colonies, such as Barbados and Jamaica. Rum, as a finished product, was also imported from there. The type of rum produced there, which is still the favored type among Bajans and Jamaicans today, is unaged white overproof, made from molasses, and that's also what they exported. It's probably also the type of rum originally made in New England. Unlike the "blanco" or "silver" types of clear rum you might be familiar with, white overproof rum shares with white dog whiskey, and especially with sugar-based "moonshine", a distinctive flavor and aroma that many find a bit off-putting. Especially anyone expecting what most folks think of as "rum" today. But that's the way rum comes out of the still, and if you're foolish enough to simply drink it that way; that's what you get. New England rum's reputation as cheap, horrible rot-gut, suitable only for those tough enough to enjoy that sort of thing may have legitimately referred to that type of rum.

But if you

pour that rum back into the same barrels the molasses came in, and load those barrels of

sweetened, darkened rum onto a ship in Rhode Island (say, on an icy February

morning) and

send it off on a year-long, constantly rocking journey into the

infernal heat of equatorial West Africa

you end up with a completely different product. Remember that the distillers

themselves

didn't sell those barrels of rum to the African slave traders; they sold

them to the ship captain (or his company). He could then sell them to anyone he

wanted to. Of course they were intended to

be used as barter for purchasing slaves, but the number of slaves to be

purchased was finite, there being only so many that the ship could hold. A

good merchant captain would be able to fill his ship for much less than all

the rum he had brought with him, and whatever wasn’t used would be his to sell

for cash when the ship returned home. In the meantime, that rum would have

spent months sloshing around on a rocking ship, mostly in intense tropical

heat, followed by possibly a chilling few weeks on its way back to New England

and perhaps further storage once it got there. So, when a well-to-do

colonial yuppie ordered a tankard of New England rum in a Boston or

Baltimore tavern, what was expected was a spirit that had a deep

copper-brown color, with the rich flavors acquired from all that barrel

contact. New England rum's reputation as being among the finest examples of

barrel-aged spirit, with subtle nuance not found in even the best Caribbean

rums may very well have referred to THAT type of rum.

In any

case, it all went away. In 1763 Paris began to allow rhum from the French

West Indies to be sold in France, thus removing New England's prime source

of cheap contraband molasses, the British ended the slave trade (at least as

a major business) in 1774, and in 1776 we filed for divorce from the Crown.

At that point, trade (at least dependable, legitimate trade) with the

British Caribbean colonies came to an abrupt halt. And not long afterward

trade with our new allies, the French changed with the French revolution and

subsequent wars with Britain. The Caribbean sources of both molasses and rum

were becoming less and less dependable. In 1803 France sold New Orleans to

the United States and tossed in the rest of the Mississippi river valley as

well. By 1813 all but one of those New England rum distilleries had closed. Those

that appeared decades later would have borne no relationship to the original

style, and it's probably safe to guess (since we'd fallen back in love with

England by then) that the rum they produced was similar to what you'd find

in a bottle of Mount Gay or Appleton today.

Decades later, after the Civil War, rum distilleries again began to appear in New England. One of the best-known areas was Medford, Massachusetts. It was, in fact, so well-known that "Medford Rum" became synonymous with "dark, full-flavored rum from New England", regardless of just which distillery produced it. Sort of like Kleenex, or Q-Tips. Among the producers of Medford rum was the Daniel Lawrence & Sons distillery, which the Medford Historical Society traces in an unbroken line reaching all the way back to 1715. But they note that, by 1830, it was the only distillery in town. By the time the Pure Food & Drug act was passed in 1906 it had closed down as well.

By the end

of the 19th century, the production of sugar in Europe from sugar beets had

overtaken that from West Indies cane, devastating the sugar cane industry.

Beet molasses is not suitable for making rum, so rum production continued to

provide a market for molasses. But now the molasses was valued as the prime

source of revenue from cane, no longer a cheap by-product to be sold to

distillers elsewhere. Caribbean rum companies became more successful making

and marketing rum for export themselves.

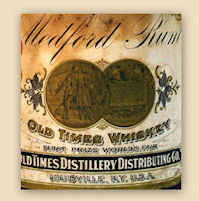

What the end of the triangle trade and changing world demand for sugar didn't finish off, U.S. National Prohibition did. We don't know if there were any operating New England rum distilleries by 1920, but that would have been the final straw for them anyway. Consider that Maine was the first state to declare prohibition, and that was in 1854. We do know that during Prohibition (as medicinal spirits) and for a few years afterward, in the 1930s, there was rum sold under familiar old brand names such as Medford, Felton, Chapin, Pilgrim, and Everett, but these were bottlings of rum made in the early 1900's, not the New England rum of a century before that. There were also American rum marketers who produced brands of rum NOT identified with New England, such as Dillinger, but these were mostly bottlings of rum imported from the West Indies. And, of course, there were some marketers who simply purchased the rights to well-known names and used them, just as they did with bourbon and rye whiskey. In the '30s one could buy rum labeled "Medford Rum", or "New England Rum", both of which were distilled in Kentucky by the Pogue family's Old Times Distillery.

Today there is a renaissance in rum production by a new breed of (mostly) young artisan/craft distillers. We say "mostly" because one of the best examples, and one of the earliest, is Phil Pritchard in Kelso, Tennessee. Phil has been making fine American rum for years, and he isn't particularly interested in duplicating an historical style; he just wants to make the best rum he can. That seems to be true of most other American rum distillers as well, including a couple important newcomers in Maryland. Others can be found all over, but of course the ones in which we are the most interested would be those located in historic rum locations, such as New England.

Lyon

Distilling Maryland was also a

rum-producing state in the 1700s, and it is again!

Blackwater

Distilling Another Maryland rum

distillery, Chris and Jon Cook's Picaroon rum emulates the French-Caribbean

style.

|

|

Story copyright © 2012 by John F. Lipman. Photo of Screech Rum label copyright © by Bill & Wendy Owens. All rights reserved. |

|