American Whiskey

August 28, 2012 |

Ned Wight is a distiller working in two traditions,

New England Rum, and Maryland Rye Whiskey.

His products are outstanding examples of both.

![]()

What a fortuitous situation

that was, as we were just at that time planning a trip through New England

and arranging to visit some distilleries along the way. Needless to say

Portland, Maine immediately joined the list.

What a fortuitous situation

that was, as we were just at that time planning a trip through New England

and arranging to visit some distilleries along the way. Needless to say

Portland, Maine immediately joined the list.Ned Wight (his name is really "Edward", but "Ned" seems so cool, considering it's the initials of New England Distilling) is, as we noted before, the direct descendent of John Hyatt Wight, whose Sherwood Distillery in Cockeysville, Maryland owns a proud spot on the short list of most influential rye whiskey distilleries of all time. Perhaps more important, though, is that Ned's grandfather -- at whose knee little Ned learned about his family's past -- was John Hyatt Wight II (there were several other Wights and Hyatts in between). You can read more about them HERE.

The Wight family is to Maryland rye pretty much what the Dant or Beam families are to Kentucky bourbon.

The Wight distilleries survived Prohibition; at least they were able to start up again and continue as an important member of the whiskey community. But the end of America's fascination for rye whiskey was approaching, and the last of the Wight distilleries closed its doors in 1958.

Despite the Wight family's Mid-Atlantic roots, Ned ended up in New England,

graduating from the University of Vermont in 1994 with a degree in Forest

Biology. And, although he spent several years working in related

industries, what really sparked his enthusiasm for working with fermented

grain was his first job out of school: he was one of the first employees of Allagash

Brewing Company, and remained there as head brewer for five years while

they became one of the biggest success

stories in microbrewing. After his brewing success, Ned worked several

years for a well-known

biological laboratory, also in Maine, never forgetting his love for working with yeast

and making good stuff for people to drink. He spent a good deal of that time

studying the art and technology of distilling fermented grain in Michigan,

Kentucky, California, and Massachusetts.

Notice we said, "fermented grain". Family heritage aside, New England Distilling's original product was gin. Specifically, the brand "Ingenium", which, like whiskey, is based on grain distillate. Since it doesn't require years of aging it's a good way to provide a saleable product for cash flow right away. In Ingenium's case, it also won awards... not a bad thing.

But it is what came next that makes New England Distilling important from our perspective. Ned and Tim decided make rum. Not just unaged white rum that bartenders could substitute for vodka, but real aged rum. Aged for 1 year in true 53-gallon ex-bourbon barrels. That might not sound like much for readers familiar with bourbon or rye whiskey, and certainly not in the scotch world, but it's just about right for decent rum. Especially in a heated warehouse. They named their rum "Eight Bells", after the Winslow Homer painting, because the Portland Museum of Art was opening an exhibit of Homer paintings at the time the rum was ready for bottling and there was much publicity. The association between seafarers (Homer's most popular subjects) and rum made the choice of brand name pretty easy.

As to whether Eight Bells is a good example of classic New England rum, it's hard to say. Historically, there were two kinds of "New England rum", each with its own characteristics, and each with it's own reputation. As a product of the "triangle trade", New England rum could be had in its raw, unaged state, which is how it was shipped. This was, by all reports, a really horrible beverage -- crude and harsh; good only for getting drunk and relieving the sick (while punishing them for their sins, of course). Of course it should be noted that the same writers who described it thus also felt that way about whiskey -- meaning raw, unaged whiskey from the local distiller. The other kind of "New England rum" was what resulted from barreling in wood and a year or so cruise down to equatorial Africa, sloshing all the way, and then across the ocean again to the Caribbean islands, and then back up to New England (probably in late fall) to be stored in freezing warehouses until spring. The resultant brown liquor, bearing the same "New England Rum" moniker, was much more well-received, and in fact compared well with the best of the Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad rums. And this became especially so after that little conflagration known as the Revolutionary War, which closed all of those British colonies to us.

At the time of our visit, New England

Distilling's Eight Bells rum is unavailable for us to taste (sold out),

and Ned is making his other aged product, Gunpowder Rye Whiskey. The name

of this brand is also historical, but more generic. For taxation purposes,

all beverage liquor is considered to be in degrees of "proof", with "100

proof" being a mixture containing 50% alcohol. The actual bottling proof

is determined by what the distiller wants the final strength to be, with

80 proof (40%) being the minimum allowed by law. In the days before

precision measuring equipment was available, the amount of actual alcohol

in the alcohol/water mixture was determined empirically by mixing equal

parts of whiskey and gunpowder, then attempting to ignite it. If it failed

to burn, then there was less than 50% alcohol in the mixture. If it did burn,

that meant the whiskey had at least a 50% alcohol content and was said to

be "100% proof".

Thus the pertinence of the name "Gunpowder" (which is bottled at a

respectable 87 proof)

Thus the pertinence of the name "Gunpowder" (which is bottled at a

respectable 87 proof)

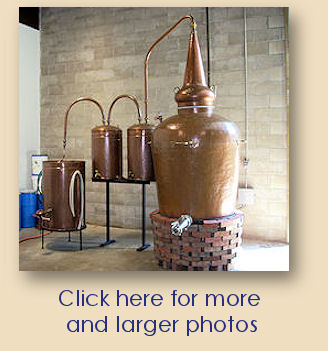

And, actually, Ned isn't making any today. This is more of an inventory management day for him, but he takes the time to reassemble the still so we can see it. Yes, the entire still is broken into sections and cleaned after every run, so Ned is dry-assembling it just for our benefit. It's a little like other pot stills we've seen, but with at least one important difference: It has twin doubler sections in addition to the main body. It is also direct-fired. Ned believes that a certain amount of caramelization is desirable, both in rum and whiskey distilling. The whiskey is aged exclusively in 53-gallon barrels, as was the Maryland rye whiskey made by Ned's family all along. Another thing that ties the New England Distillers' operation to Maryland (although it probably does little to affect the actual flavor of the whiskey) is that, in 2012 -- just weeks before our visit -- Ned learned that (1) he could have access to the one remaining brick warehouse in Cockeysville (the same one shown on our page about Sherwood) and (2) he could take the wooden ricks from there and reassemble them in his warehouse in Portland. The ricks aren't put together yet, but they're all here, numbered and stacked. Just a little bit of history brought forward.

Like true Maryland-style rye, Gunpowder's recipe calls for nearly all rye in the grain mash. 95% rye (much more than most rye whiskey), with the other 15% made up of malted rye and malted barley. The barley is the only grain not locally sourced.

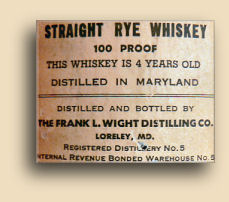

We have, in our collection, a bottle of Congressional Club Maryland Straight Rye, distilled in 1937 and bottled in 1941 in Loreley, Maryland by The Frank L. Wight Distilling Company. We have brought it with us on this journey and are proud to share what remains of it (yes, it's been enjoyed by many since we obtained it) with Ned. Unfortunately Tim Fisher isn't here this week, but he won't miss out since we decanted the remaining portion into another bottle and are leaving it with Ned. He promises to share some with Tim.

June 20, 2014

UPDATE

Today a very nice young man from FedEx brought us a package from Ned Wight containing a full bottle each of New England Distilling's Maryland Rye Whiskey, Gunpowder, and their New England Rum, Eight Bells. What a terrific surprise.

We don't usually do tasting notes. First, because we don't believe in tasting notes, and, second, because we're really, really bad at them.

So these aren't tasting notes. You'll find no mention here of vanilla, or caramel, or rutabagas, or dark, pitted fruit (olives?). All you can learn from us about a spirit you haven't tried before is what little we now know and can communicate.

And if you've already tried a spirit and are still looking for tasting notes to tell you what you ought to be tasting, well, shame on you.

The fact is that we have tasted many Maryland and East-of-the-Alleghenies rye whiskeys. All but a few, of course, are examples from before the 1980s, most from the '30s, some from before Prohibition. We have also tasted some very fine modern examples of what their distillers believe to be this sort of whiskey.

Gunpowder is the only one that tastes the way old Maryland rye probably would have tasted at less than two years of age. If Ned is reserving any barrels of this whiskey until they reach four years old (and we sure hope he is), it's going to taste hauntingly like the four-year-old Congressional Club produced by his great-grandfather.

As for the Eight Bells New England rum... well, no one knows what New England rum really tasted like. Its reign was over long before bottled product was sold. One would have to guess that Eight Bells probably doesn't taste "authentic". What it DOES taste, though, is wonderful. The best of the New England rums, in their heyday, would have competed with rum from Barbados and Trinidad. Probably Guyana, too. Eight Bells, at one year of age, reminds us of Zaya or Zacapo. Those are among John's all-time favorite brands of rum, although both are much older (aged 12 years). Zacapo is made in Guyana; Zaya is from Trinidad, although it used to be made from the same South American molasses as Zaya and has done its best to duplicate that desirable flavor profile in its new location.

Ned buys his molasses exclusively from South America.

When

there are barrels of Eight Bells that have reached 12 years of age, I

believe this rum will be as good or better -- and in all the same ways --

as those two.

When

there are barrels of Eight Bells that have reached 12 years of age, I

believe this rum will be as good or better -- and in all the same ways --

as those two.

It will be fun to visit Portland, Maine again.

Oh, and just in case you go to visit Ned, the lobstah rolls at the Portland Lobster Company are terrific!

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2012 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|