American

Whiskey:

April

29,

2011

--

Tennessee

Whiskey

Country

The George A.

Dickel Distilling Company

We spent last night at the Best Western Celebration Inn in Shelbyville, about a half hour from the George Dickel Distillery at Cascade Hollow. And we awake this morning nearly an hour later than we’d planned, upset that the motel has missed a requested wakeup call. Fortunately, before John gets a chance to embarrass himself by calling the front desk, Linda remembers that we are now in the Central Time Zone – an hour earlier than our watches! Ten minutes later -- and right on schedule, of course -- the phone rings.

Today we are going to explore the entire (legal) Tennessee whiskey industry,

which consists of only three distillers located less than twenty miles from

one another (well, yes there is a fourth and fifth, Corsair and Collier &

McKeel, in Nashville, but we

visited those already on our way here). Our first stop is at the

George

A. Dickel distillery just outside the unincorporated village of

Normandy, near Tullahoma. Only a couple days ago this area was being

deluged with some of the heaviest rains they've ever had. Thunderstorms

and winds (the same storm system that devastated parts of nearby states)

took down trees and electric poles. But this morning is brilliantly sunny

and dry. Getting to the distillery site involves traveling along several

miles of lovely country back roads, set in the lush spring-green hills and

valleys. As we approach the distillery, we are again struck by its

setting, easily the most beautiful of any distillery we've ever visited.

The road winds through a tiny valley, and set against the hillsides on

both sides, the visitor center, the charcoal-making area, and, across the

road, the distillery itself are clean and attractive.

The origins of commercial whiskey distilling in Tennessee

go way back, and they are impressive, indeed. According to

Henry C. Crowgey, in his book

Kentucky Bourbon: The Early Years

of Whiskey-Making, Evan Shelby operated the East Tennessee Distillery

near what is now Bristol in Sullivan County as early as 1771. Kay

Baker Gaston, in an article she published in the Journal of the

Kentucky-Tennessee American Studies, quotes

Herbert Asbury (The

Great Illusion: An Informal History of Prohibition) as stating that

the fourth National Census, taken in 1820, places Tennessee as having "...

more capital invested" and employing "... more men in the

production of spirits than any other states in the Union", other than New

York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.

Well, along with this healthy, successful distilling industry came an equally healthy and successful temperance and anti-saloon sentiment. In 1877 the state enacted laws prohibiting the sale of intoxicating beverages within four miles of a schoolhouse, in certain specific cases. Over the next couple decades those cases became progressively less restrictive until, by 1899 there was effectively no place in the state where whiskey could legally be sold. In 1910, long before the 18th Amendment brought National Prohibition, Tennessee had already amended its own constitution to prohibit the production, distribution, and even use of alcohol. Of course, just as would be the case nationwide a decade later, there was always plenty of alcohol available. Still, that pretty much destroyed the legitimate distilleries in Tennessee. And for the most part, they never recovered.

One that did, of course, was Jack Daniel's

distillery in Lynchburg. In the 1950s, the Motlow family, which owned Jack Daniel's, began entertaining offers to buy them out. They had several suitors, but the two main ones were the family-owned Brown-Forman company in Louisville, and the Schenley company. Brown-Forman won, and they purchased Jack Daniel's in 1955.

The great Schenley company was dumbfounded. How could

this be? It didn't happen, of course, but what they did accomplish was to build a very capable alternative, and one which many people find to be even superior in quality.

At this point, it's probably a good

idea to bring up a little bit about this particular distillery's history.

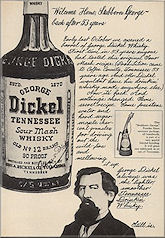

First of all, it never was the George A. Dickel Distillery until very

recently. And, despite the lovely, but largely fictional, story that

its current owners, the Diageo conglomerate, offers (and in all fairness,

so did its previous owners, and the ones before them, and so on), George

(and his wife Augusta) Dickel

never made a drop of whiskey in his life.

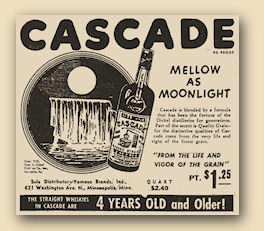

Well, no matter what you call it, after 1911 what you'd call it was... closed. National Prohibition was still ten years to come, but Tennessee had already outlawed the production and sale of alcohol beverages. The distillery was closed, but the company itself moved to Kentucky, where they continued producing whiskey in rented facilities at the Stitzel distillery in Louisville until after the Prohibition Amendment was repealed. In the early 1940's they moved to the George T. Stagg distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky, which was operated by Schenley. Schenley had already purchased the Cascade brand, and was using that as a price leader (i.e., cheap bourbon) brand. And that brings us back to the mid-50s and Brown-Forman's purchase of Jack Daniel's. Schenley already owned the Cascade brand. They had bought that, along with the rest of the company, from the Shwab family in 1937. But they had been using that brand to market low-priced, base-quality bourbon whiskey, mostly made at their Indiana distillery. Very shortly after Brown-Forman got the Jack Daniel's deal, Schenley assigned distiller Ralph Dupps the awesome task of reviving a distillery and brand that no longer existed, other than on paper.

Dupps, who was working at the Bernheim

Distillery in Louisville, making I. W. Harper bourbon, was already very familiar with

Cascade whisky, and he was a major fan. His reaction to that assignment was

basically

"Hoo-hah! Lets' git 'er done", and he proceeded to do exactly that. Did he succeed? Well, for most people who have compared it with the whiskey it was intended to compete against, yes. The whisky (it is called "George Dickel" now, because the Cascade brand is still owned by Schenley's successor, Buffalo Trace) is quite different from it's other Tennessee whiskey competitor, and in fact, has a flavor much more reminiscent of pre-prohibition whiskies than most other current American whiskies.

The legend, and much of the

officially-dispersed history, of this whiskey is almost completely a

product of marketing professionals. At first it was Schenley, certainly no

strangers to creating legends and history from scratch. Schenley then sold

their company to Diageo who, while they treat their brands with a bit more

integrity than Schenley did, little of that has appeared in the

current tales being published about George Dickel. But when you visit this

distillery, please don't embarrass your tour guide by asking about the Shwabs (they never mention the Shwabs), or question their contention that

Georgie and his lovely wife Augusta came here and said, "yes, darling,

this is where we shall build our distillery" (there is no evidence that

George Dickel ever set foot in Normandy, Tullahoma, nor anywhere near

Cascade Hollow) This isn't meant to be an exposé. Readers of these web pages should understand that a big part of American spirits' appeal (as well as that of everyone else's spirits) is the romance and legendary tales that surround the various expressions. It doesn't really matter that some (or all) of those legends are bogus. It's what distinguishes distilled spirits from milk or Coca-Cola (well, Coke® has its own "created" legends; and good for it). What a visitor to the George Dickel Distillery needs to know is that you will be shown through a lovely distillery plant, in probably the most beautiful setting you will ever see, and that the whiskey that is produced here -- and every drop in all the world is, indeed, produced right here, by the very people you will be meeting on your tour -- is among the finest examples, Tennessee or otherwise, that America has to offer.

On the other hand, if you'd enjoy

reading some articles that present, in astounding detail,

In 1987, Schenley sold the Dickel

brand and the distillery to Guiness, who, in that same year, became part

of a merger that produced United Distillers. Then, ten years later,

United Distillers merged with Grand Metropolitan to create a brand new

super-conglomerate, Diageo, which is now the world's largest producer of

distilled spirits.

Not much, really. Ralph Dupps, who

died in 2007, is (or should be) credited with creating the modern George

Dickel Cascade Whisky. His protégé,

Bill Bruno, continued as master distiller through the changes that

President Reagan's de-regulation brought about, and is pretty much uniquely

responsible for the the product

we know today as George Dickel Tennessee Whisky. And

distiller Dave Backus further continued

the tradition until the mid-2000's when he was replaced by the current

master distiller, John Lunn . And of course, as is typical of corporations in

general, and especially those in the alcohol beverage industry, the

existence of neither Bruno nor Backus is acknowledged in any of the

company's publicity, including its official history. So, about the tour itself... We begin at the general store, which leads to the visitor center, a big, rustic wood, lodge-like room with an enormous fireplace and couches, displays of Cascade Distillery's past and present, and even a little kitchenette-looking area that might someday become a tasting bar -- if Tennessee ever grants a license to offer samples. In another part of the room is the obligatory flat-screen TV and DVD player for showing the (well, at least "a") history of George Dickel. There are also several displays of distillery models and Dickel products.

It is from here that the visitor tours start, and this is where we meet

our tour guide, Gina Mathias. Besides ourselves, there is only one other

couple on this tour, so it's almost a private tour.

The first stop is just outside the

visitor center, where the maple boards are

stacked and burned to produce charcoal. The process that separates

Tennessee whiskey from normal bourbon -- in fact, it defines Tennessee

whiskey for most people -- is the "mellowing" that is

accomplished by slowly trickling the newly-distilled whiskey (or "whisky"

in this case; George Dickel insisted on leaving out the "e" because that's

the way the Scots spell it) through several feet of maple charcoal before

putting it into the barrels. That charcoal is produced right here, and

Gina Inside the distillery proper, Gina shows us the mills that grind the corn, rye, and barley malt, and the cookers and fermenters where that cereal is turned into whiskey mash. There are nine fermenters altogether, each of which holds around 20,000 gallons of grain and water. Most bourbon distilleries we have visited use #2 yellow corn, some local, some from other areas. Basically it's cattle-feed, but that's good enough for making whiskey. At Dickel they use locally-grown #1 Tennessee yellow corn, which they compare to sweet corn. Most of the people we know, including ourselves, notice a distinctive taste that is unique to George Dickel whiskey; perhaps it is this choice of their main ingredient? At any rate, they use 74% of that corn, along with 8% each of rye and malted barley, in their recipe. They use dry yeast to ferment the grains, and they dose the mash with the yeast from the top. Distillation is done in a gleaming all-copper column still, then the whisky is re-distilled in a stainless steel pot still, known as a doubler, before being transferred to the "mellowing" phase. Here, it is chilled to about 45 degrees and then allowed to dribble slowly (about a gallon/minute) through a column of the maple charcoal pieces we spoke of above. According to the Cascade literature, it is this chilled filtration that gives Dickel its distinctive flavor.

Gina takes us

to see all the places the tour normally covers, of course, but she is able (and happy)

to spend a lot more time with us at each stop. She points out details that

shows us clearly how each process is done, and also shows how much she is

aware of the way the distillery works –

Photography inside the production

facilities is not allowed (although there are some really good pictures to

be found posted on other websites - check out Flickr). Gina

explains that this exasperating "rule" is due to government regulations

meant to ensure our safety, not because they don't want their competitors

to see. No cell phones are allowed either. That's another "safety"

restriction which appears to have become necessary only now that many cell

phones include cameras. Apparently the fumes in other distilleries are

less explosive, since no one else seems to have such restrictions...

except at Jack Daniel's. Okay, so maybe it's not federal

restrictions; maybe it's the state of Tennessee that forbids photography

in production areas. Except that when we visit with Phil Pritchard

at his distillery in Kelso later today, we will find he has no such

restrictions at all;

Gina then gives us a demonstration of how the barrel plays an

important role in the production of whiskey, and she shows us a mock-up

of their barrel warehouse, although the real warehouses are located back in

the hills, too far to walk to. George Dickel whisky is aged for five to

seven years on-site, at several 6-story warehouses located in the hills

behind the distillery, but after that, the whisky is dumped from the

barrels to a tanker and shipped to their bottling facility in Maryland.

After the tour we return to the general store. The last time we were here, twelve years ago, we bought some souvenirs, including a bottle of 10-year old Special Reserve. At that time, they couldn't sell anything that would have been available at normal retail outlets, only specialty bottlings. Since then, the laws have changed, virtually flip-flopping, and they're no less strange. Now they CAN'T sell you anything that's not available to the general public, only products offered through normal distribution channels. Go figure! Some people who are familiar with things offered on eBay and yard sales might recall the familiar powderhorn-shaped bottles. The Dickel company obtained special legal permission (T.C.A. §57-3-204) to allow them a retail liquor license, restricted to selling only special souvenir bottlings of their product. By the time of our visit, nearly fifty years later, that description has been extended to include the Barrel Select (which is not really a souvenir but usually pretty scarce in normal retail stores) but no other Dickel whiskies. There are, of course, lots of other George Dickel souvenir products available.

|

|

|

|

Story and original photography

©1998-99 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|

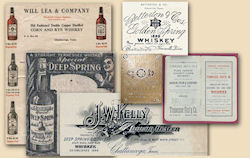

Dickel was a Nashville merchant

who, like many merchants, sold clothing, shoes, housewares, groceries, and

liquor. Merchants who sold their own brand of spirits usually obtained them from whatever vendors they pleased. Dickel was probably no

exception, other than that he eventually narrowed his vendor list down to

just the Cascade Hollow distillery near Normandy. That distillery was

owned by Matthew Sims and McLin Davis, who was the distiller there. The Cascade

Distillery itself was never owned by the George A. Dickel Company, but its whisky was

sold as George A. Dickel's Cascade Whisky. In 1888, Matthew

Sims sold his share to Victor Shwab, who was George Dickel's partner, and

ten years later Sims' heirs sold him the remaining interest, which gave

Victor Shwab complete ownership of the distillery. Shwab was more than

just George Dickel's partner, he was also his brother-in-law. George

Dickel died in 1894, leaving his interest in George A. Dickel & Company to

his widow, Victor's sister-in-law (Augusta, the "A" in "George A. Dickel",

was George's wife as well as it's chief financier; her sister was Emma,

married to Shwab).

Dickel was a Nashville merchant

who, like many merchants, sold clothing, shoes, housewares, groceries, and

liquor. Merchants who sold their own brand of spirits usually obtained them from whatever vendors they pleased. Dickel was probably no

exception, other than that he eventually narrowed his vendor list down to

just the Cascade Hollow distillery near Normandy. That distillery was

owned by Matthew Sims and McLin Davis, who was the distiller there. The Cascade

Distillery itself was never owned by the George A. Dickel Company, but its whisky was

sold as George A. Dickel's Cascade Whisky. In 1888, Matthew

Sims sold his share to Victor Shwab, who was George Dickel's partner, and

ten years later Sims' heirs sold him the remaining interest, which gave

Victor Shwab complete ownership of the distillery. Shwab was more than

just George Dickel's partner, he was also his brother-in-law. George

Dickel died in 1894, leaving his interest in George A. Dickel & Company to

his widow, Victor's sister-in-law (Augusta, the "A" in "George A. Dickel",

was George's wife as well as it's chief financier; her sister was Emma,

married to Shwab).

And

when she died in 1916, the entire company, including

the distillery, became the realm of her brother, Victor Shwab. The

George A. Dickel's Cascade Whisky brand was already very well-known,

and Victor did not change the name; otherwise this fine product might have

been known as Shwab's Cascade Whisky.

And

when she died in 1916, the entire company, including

the distillery, became the realm of her brother, Victor Shwab. The

George A. Dickel's Cascade Whisky brand was already very well-known,

and Victor did not change the name; otherwise this fine product might have

been known as Shwab's Cascade Whisky.  First, he

located the site of the original Cascade Hollow Distillery. Unfortunately,

it would not be possible to rebuild what was once there. So he purchased

the adjacent property, which accessed the same water source, Cascade

Spring, and began construction of a modern facility that he felt would be

capable of producing the

finest Tennessee-style whiskey ever made. That was in 1958. He had a few

things going for him. One of those, of course, was the water. That really

does make a difference. Another was the supposedly-original Shwab recipe

(it would really have been McLin's recipe, but that's just the way whisky

folks are) . It's

competitor over in Lynchburg claims continuity back to Jack Daniel's

original recipe, but there's no evidence of that. In fact, some would say

Jack Daniel's is not very far from Old Forester in its flavor, with the

addition of the smoky maple leaching process. It certainly does not taste much

like George Dickel whisky.

First, he

located the site of the original Cascade Hollow Distillery. Unfortunately,

it would not be possible to rebuild what was once there. So he purchased

the adjacent property, which accessed the same water source, Cascade

Spring, and began construction of a modern facility that he felt would be

capable of producing the

finest Tennessee-style whiskey ever made. That was in 1958. He had a few

things going for him. One of those, of course, was the water. That really

does make a difference. Another was the supposedly-original Shwab recipe

(it would really have been McLin's recipe, but that's just the way whisky

folks are) . It's

competitor over in Lynchburg claims continuity back to Jack Daniel's

original recipe, but there's no evidence of that. In fact, some would say

Jack Daniel's is not very far from Old Forester in its flavor, with the

addition of the smoky maple leaching process. It certainly does not taste much

like George Dickel whisky.

Gina

spends as long as necessary at each stop, and she is happy to answer

as many questions as we have to ask. We couldn’t imagine a more personable

and knowledgeable guide.

Gina

spends as long as necessary at each stop, and she is happy to answer

as many questions as we have to ask. We couldn’t imagine a more personable

and knowledgeable guide.

not

just what the tour guides are trained to know (you might want to remember

that when we get to Jack Daniel later on today).

not

just what the tour guides are trained to know (you might want to remember

that when we get to Jack Daniel later on today).  nor

did either of the distillers we met yesterday at Corsair and Tennessee

Distilling (Collier & McKeel) in Nashville.

nor

did either of the distillers we met yesterday at Corsair and Tennessee

Distilling (Collier & McKeel) in Nashville.