It Wasn't Always Bourbon,

Y'know...

The whiskey of the twenty-first century is whiskey that has

been pretty much cut loose

from the stereotypes of the 1900's. Such ideas as that bourbon

can only be made in Kentucky; that American whiskey can only be made from

corn or rye; that any good whiskey must be aged for at least whatever number of

years the current tax laws allow; that whiskey is only made to be drunk

neat. The beginning of the current century is exploding with innovative

spirits made from "new" grains, made in new ways, and targeted at new

audiences.

The whiskey of the twentieth century was mostly the whiskey of a relatively small part of Kentucky. Known as Bourbon,

some say because of the area with which it was first identified, it was a

whiskey made mostly from corn and is still what people usually think of when

they order American whiskey. Although most people don't realize it,

bourbon can be made anywhere within the United States, but before the

2000s nearly all of

it came from Kentucky.

The whiskey of the nineteenth century

was the whiskey of a similarly small area in western Pennsylvania. Known

as Monongahela, from the river that runs through much of that country, it

was a whiskey made mostly from rye. It didn't taste exactly like the rye

whiskey we know today, and it probably didn't taste anything like the

blended Canadian whisky that Americans tend to call "rye". It became

popular enough that the style was copied in other places, such as eastern

Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, and especially Maryland, where a variant

developed with characteristics of its own. In 1810, when Kentucky produced

2,220,773 gallons of distilled spirits, Pennsylvania barreled up no less

than 6,552,284 gallons, most of which was prime Monongahela rye. There are

only a few rye whiskeys made today, and all are from Kentucky. They're

more closely related to the Maryland variety than to the west

Pennsylvanian. And until this millennium not a single commercial whiskey distillery remained

operating in Pennsylvania or Maryland.

The whiskey of the eighteenth century --

such as there was of it -- was the whiskey made in Virginia, Maryland,

Delaware, New Jersey, the Carolinas, and Georgia. It was mostly distilled

for home consumption but some was produced commercially. It, too, was

mostly rye. Corn, or rather maize, didn't take off in popularity until the

Kentuckians worked their magic on it much later. In fact, long before

Indian maize was used for making whiskey, colonial and early American

distillers understood the eastern European word "korn", meaning "grain",

to refer to rye. That was the kind of whiskey George Washington distilled

and it was very different indeed from the bourbons and ryes we know today.

And by 2002, Old Potrero is not alone. Rodney Facemire in

southern West Virginia began producing legal clear, unaged rye whiskey and bottling it

at a less-threatening 80 proof. He was instrumental in getting laws passed

that allowed small distilleries to exist legally for the first time since

Prohibition, and much of the current environment for artisan distillers

can be directly or indirectly traced to his operation at Kirkland Winery

in Summerville. His Isaiah

Morgan Rye tastes remarkably like young cognac. It's also probably a

lot closer to the sort of rye whiskey that George Washington's customers were drinking than the

125+ proof Fritz Maytag distills it at.

The whiskey makers in the Monongahela River valley made the

same kind of whiskey. And they sent their whiskey to the same east coast

markets for sale. But by the time it had been stored in warehouses and

then traveled the long route from there to civilization it had spent

months in barrels and picked up a flavor and a deep reddish-brown color

that became characteristic of the type.

But our web site isn't about tasting whiskey. It's about

visiting the places where it is (or at least was) made. And that's what

we're about to do. There's a lot packed into these pages, because there's

a lot more than meets the eye. In fact, there's very little to meet the

eye anymore, and we will find ourselves spending more time trying to find

some of these sites than actually visiting them. Our journey into the

misty, half-secret realm of whiskeys-that-are-no-more will have us

traveling backwards in direction and every which way through time as we

visit the sites where some of Pennsylvania's and Maryland's proudest

distillers of fine American Rye once fired their stills and drove bungs

into their barrels. Along the way, we'll visit areas where unthinkable

ideas of independence and freedom were formed and would later be put to

the test. George Washington really did sleep here. In fact he owned quite

a bit of it. There was whiskey being made here then, by farmers and by

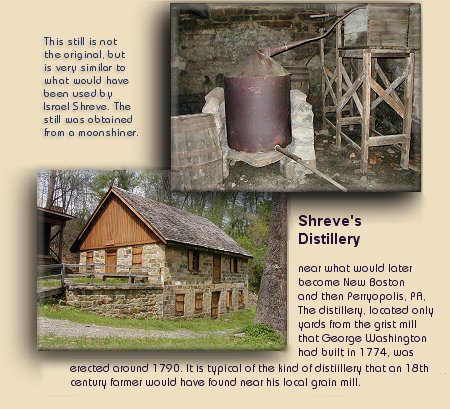

millers, and we'll visit the site where farmer (and Revolutionary War

hero) Israel Shreve operated his small distillery and grist mill in the

1790's. Carefully restored to its original condition, it's one of the

earliest whiskey distilleries in Pennsylvania.

But it wasn't always bourbon, y'know...

Despite the contrivances of abstentionists to connect their

viewpoint with our proud Puritan forebears, the fact is that the colonists

of British North America drank beverage alcohol. They drank a LOT of

beverage alcohol. In fact, by today's standards their average per capita

consumption would be considered quite alarming. In the early 1700's the

average annual per capita consumption of alcohol was over three and a half

gallons (pure alcohol; that would be over seven gallons at 100 proof), or

about double today's rate. About a third was in the form of beer or wine,

the rest was distilled spirits.

And hardly a drop of that was whiskey.

Rum was by far the preferred spirit, with fruit brandy

(especially peach, apple, and pear brandy) making up most of the rest.

As settlement expanded westward toward the mountains

commercial areas and towns began to form, and with them rose a market for

locally-obtainable whiskey. In those days, before the later temperance

movements had created a different sentiment, whiskey was regarded as a

necessary article of food, no different from beef or bread. And about the

same time that butcher shops, bakeries, and candlestick manufacturers

appeared, so did commercial whiskey distilleries.

For one thing, farmers were quickly discovering the

advantages of having a portion (sometimes a large portion) of their crop

converted to whiskey for transport to market. As the frontier spilled over

the Alleghenies into what would later become western Pennsylvania that

advantage became a requirement. Transporting their grain to New Orleans

down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers was not yet feasible, due both to the

distance and the hostility of the Spanish who claimed rights to that area.

The only existing road leading east across the mountains to market was

extremely difficult and dangerous. Their surplus produce must rot unless

it could be manufactured into spirits which could be consumed at home or

carried to a market.

Typically not long after a grist mill was built to serve

area farmers a distillery would be set up, sometimes as a separate

business or often as another service offered by the miller. The farmers

would store a portion of their grain (which might also be a service

offered by the larger area mills) and have enough of the rest ground into

meal or flour as needed to sustain his family for the year. The rest would

be mashed and distilled into whiskey. And in a barter-based society with

an overabundance of agricultural products, whiskey served as an excellent

medium of exchange.

Which, along with several miles of twisty and confusing

back-country roads, brings us to Perryopolis, on the Youghiogheny river.

Click here and

we'll visit the basic farmer's distillery operated by Col. Israel Shreve

in the 1790s..

.

American

Whiskey:

![]()

IN

FACT it didn't even start out being Whiskey at all. But

distilled alcoholic beverages were an integral part of America right from

the very beginning, and the "Spirit" of freedom in the New World was far

more than just a figure of speech. The founding of the American colonies and

their transformation into a free and independent new nation is richly

intertwined with the history of American whiskey. You cannot possibly

increase your understanding of the one without adding to your appreciation

of the other. And so we decided to spend some time exploring a few of the

sites among the hills and valleys where it all began.

IN

FACT it didn't even start out being Whiskey at all. But

distilled alcoholic beverages were an integral part of America right from

the very beginning, and the "Spirit" of freedom in the New World was far

more than just a figure of speech. The founding of the American colonies and

their transformation into a free and independent new nation is richly

intertwined with the history of American whiskey. You cannot possibly

increase your understanding of the one without adding to your appreciation

of the other. And so we decided to spend some time exploring a few of the

sites among the hills and valleys where it all began.

For

one thing, it wasn't reddish brown, because it wasn't aged in barrels. In

fact, it wasn't aged much more than however long it took to get it home

from the distillery. Fritz Maytag, the gentleman who brews Anchor Steam

Beer in San Francisco makes a rye whiskey that he believes comes as close

as possible to duplicating that whiskey. He calls it

Old

Potrero, also for the location -- in this case a hill in San

Francisco. By federal law, he can't even label it "Rye Whiskey", because

the law defines rye whiskey as a completely different product. It's

labeled "Single Malt Whiskey", as if it were a kind of scotch (he does

bottle a product that meets the legal definition, and is labeled "Rye",

but it isn't quite the same). Old Potrero is hard to find and costs a lot

because Fritz doesn't make much, but if you want to understand the roots

of American whiskey you should have a bottle. Prepare to be surprised at

the flavor; it probably won't be your favorite whiskey. But then again, it

might. John (the "Jaye" part of "L and J Dot Com") loves it. But then John

also loves pure, unaged corn whiskey too.

For

one thing, it wasn't reddish brown, because it wasn't aged in barrels. In

fact, it wasn't aged much more than however long it took to get it home

from the distillery. Fritz Maytag, the gentleman who brews Anchor Steam

Beer in San Francisco makes a rye whiskey that he believes comes as close

as possible to duplicating that whiskey. He calls it

Old

Potrero, also for the location -- in this case a hill in San

Francisco. By federal law, he can't even label it "Rye Whiskey", because

the law defines rye whiskey as a completely different product. It's

labeled "Single Malt Whiskey", as if it were a kind of scotch (he does

bottle a product that meets the legal definition, and is labeled "Rye",

but it isn't quite the same). Old Potrero is hard to find and costs a lot

because Fritz doesn't make much, but if you want to understand the roots

of American whiskey you should have a bottle. Prepare to be surprised at

the flavor; it probably won't be your favorite whiskey. But then again, it

might. John (the "Jaye" part of "L and J Dot Com") loves it. But then John

also loves pure, unaged corn whiskey too.

An

example of Monongahela-type rye whiskey can be found pretty easily; just

look for Old Overholt in the bottle with Abraham Overholt himself glaring

sternly at you from the label. It's not really Monongahela rye. It's made

in Kentucky. By Fortune Brands, who also make a rye under their Jim Beam

label. But it doesn't taste like Jim Beam Rye, or any of the other fine

Kentucky rye whiskeys. It's flavor is quite different, and very

reminiscent of the real article, distilled in Pennsylvania at the Broad

Ford of the Youghiogheny river. and if you mix a little of your Old

Potrero with it, you'll have a pretty good idea of what that whiskey might

have really tasted like. There's also a Canadian rye whiskey, Lot No. 40,

that is directly descended from the original Monongahela types, and also

has that very distinctive flavor.

An

example of Monongahela-type rye whiskey can be found pretty easily; just

look for Old Overholt in the bottle with Abraham Overholt himself glaring

sternly at you from the label. It's not really Monongahela rye. It's made

in Kentucky. By Fortune Brands, who also make a rye under their Jim Beam

label. But it doesn't taste like Jim Beam Rye, or any of the other fine

Kentucky rye whiskeys. It's flavor is quite different, and very

reminiscent of the real article, distilled in Pennsylvania at the Broad

Ford of the Youghiogheny river. and if you mix a little of your Old

Potrero with it, you'll have a pretty good idea of what that whiskey might

have really tasted like. There's also a Canadian rye whiskey, Lot No. 40,

that is directly descended from the original Monongahela types, and also

has that very distinctive flavor.

We'll

also visit Pennsylvania's last commercial whiskey distillery, which closed

in the late 1980's. We'll sift through the rubble and broken bricks of

what was once Old Overholt's distillery at Broad Ford, and we'll marvel at

the fact that Broad Ford itself, nearly a hundred fifty years before that,

had played an important role in America's settlement west of the Allegheny

Mountains. We'll hike along a twisting, narrow trail through the woods to

visit a small pile of broken stones and twisted copper equipment marking

where King's Maryland Rye was being made nearly a century ago. We'll drive

from the site of a pre-Civil War Monongahela distillery, to that of a

Prohibition-era moonshiner's outdoor mountain still, and on to the empty

shells of a huge facility in Baltimore where Four Roses Whiskey was made

during the twentieth century, and Baltimore Pure Rye in the nineteenth.

We'll

also visit Pennsylvania's last commercial whiskey distillery, which closed

in the late 1980's. We'll sift through the rubble and broken bricks of

what was once Old Overholt's distillery at Broad Ford, and we'll marvel at

the fact that Broad Ford itself, nearly a hundred fifty years before that,

had played an important role in America's settlement west of the Allegheny

Mountains. We'll hike along a twisting, narrow trail through the woods to

visit a small pile of broken stones and twisted copper equipment marking

where King's Maryland Rye was being made nearly a century ago. We'll drive

from the site of a pre-Civil War Monongahela distillery, to that of a

Prohibition-era moonshiner's outdoor mountain still, and on to the empty

shells of a huge facility in Baltimore where Four Roses Whiskey was made

during the twentieth century, and Baltimore Pure Rye in the nineteenth.

And

we'll get there by traveling over the first federally-paved "2-lane

interstate highway" for automobiles in America, the Lincoln Highway, as

well as the first federally-built road across America, period... the

National Pike.

And

we'll get there by traveling over the first federally-paved "2-lane

interstate highway" for automobiles in America, the Lincoln Highway, as

well as the first federally-built road across America, period... the

National Pike.

Whiskey

was a homespun farm product, usually produced and consumed by the same

farmers who made their own clothing and furniture. In Catoctin Park, near the Camp David presidential retreat in Maryland, the

National Park

Service has set up a display on the former site of a notorious (and large)

moonshine operation once known as Blue Blazes. That had been a

25,000-gallon operation that was raided and destroyed in July of 1929, but

the still equipment you can visit on the banks of Distillery Run today is

quite different from that setup. The little 50-gallon Blue Blazes still on

display may not do justice to the operation for which the site is named,

but it is an excellent example

of the type of still an 18th century farmer would have for converting his grain crops to

transportable liquid. Before the 1791 Excise Tax, just about every farm

had its own whiskey still.

Click here and

we'll take a walk through the Maryland woods and visit this one...

Whiskey

was a homespun farm product, usually produced and consumed by the same

farmers who made their own clothing and furniture. In Catoctin Park, near the Camp David presidential retreat in Maryland, the

National Park

Service has set up a display on the former site of a notorious (and large)

moonshine operation once known as Blue Blazes. That had been a

25,000-gallon operation that was raided and destroyed in July of 1929, but

the still equipment you can visit on the banks of Distillery Run today is

quite different from that setup. The little 50-gallon Blue Blazes still on

display may not do justice to the operation for which the site is named,

but it is an excellent example

of the type of still an 18th century farmer would have for converting his grain crops to

transportable liquid. Before the 1791 Excise Tax, just about every farm

had its own whiskey still.

Click here and

we'll take a walk through the Maryland woods and visit this one...

For

the most part, only those products could be taken over the mountains as

had feet of their own. A horse, it was said, could carry only four bushels

of grain across the mountains; but he could take twenty-four bushels when

converted into liquor.

For

the most part, only those products could be taken over the mountains as

had feet of their own. A horse, it was said, could carry only four bushels

of grain across the mountains; but he could take twenty-four bushels when

converted into liquor.