American Whiskey

April 15, 2014 |

|

A "New Riff" on an Old Tradition

![]()

THREE SECONDS WORTH of Keith Richards' guitar and

you know the Rolling Stones are breaking into Jumpin' Jack Flash.

Likewise, just how many notes does Jimmy Paige have to strum on his acoustic

12-string for you to know you're about to visit the lady who's sure all that

glitters is gold?

These instrumental signatures are called "riffs" in jazz, rock,

and pop music, and no serious musician in any of those genres

should expect to find employment if they can't duplicate them for each song

their potential band intends to play. It's not that a guitar player (or sax

player, or piano player) wants to spend his whole career covering songs made

popular by other musicians, but that's the way you learn your craft.

As for the riff itself, well that simply defines the song, now, doesn't it?

After all, how many bands have you heard play Jumpin' Jack Flash? I mean bands

with their own style and sound, not just local cover bands. Guns 'n Roses played it (with

acoustic guitar, no less); Rick Derringer played it (with and without Johnny

Winter); Aretha Franklin sang it; Motörhead, Thelma Houston, the Beach Boys, Leon

Russell,... even David Cook performed it on American Idol.

None of these sound like

the Rolling Stones, nor want to.

But if you're going to play Jumpin' Jack Flash you'd better be

able to lay that riff down with some authority.

'Cause they pretty much all sound the same, don't they? Yup, sure 'nuff!

Well, did you know that Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart recorded Jumpin' Jack Flash, too, in 1969?

(Yes,

that Boyce & Hart of The Monkees and other '60s pop stardom).

And their version didn't use that opening riff.

Neither did the version recorded by Alex Chilton, of the Box Tops (The Letter)

in 1970.

And for people who appreciate good Rolling Stones music, that makes them all the

more interesting and collectable.

People who appreciate American whiskey often feel the same way.

For one thing, the "catalog" is very slim: the TTB (who regulates what

we can call spirits) makes it very clear that there are only a handful of

beverages distilled from fermented grain that can even be labeled as anything

but the generic term, "spirits". The definitions of "whiskey", "bourbon", "rye" and other familiar

types really are etched in stone, the "stone" being the

Code of Federal

Regulations, Title 27, Volume 1,CHAPTER I, PART 5, Subpart C -- Standards of

Identity for Distilled Spirits.

And anyone who wishes to play that song had better know the opening riff...

Or do they? Well, no, you can't play Jumpin' Jack Flash with any sense of

conviction if you don't know how to play that riff.

But that doesn't mean you have to actually play it. You could

come

up with your own riff.

A new riff.

And that's exactly what the new distillery located at the far northern border of

Kentucky is doing.

We began this journey through America's distilleries by visiting the handful of

existing bourbon makers, then began looking into the many distilleries that have

passed into history. Along the way, we looked at a few intrepid folks dedicated

enough -- or crazy enough -- to attempt to build new distilleries and market new

spirits made from grain. There weren't many. And those who tried found

themselves spending most of their time (and their funds) petitioning, cajoling,

and schmoozing with politicians to get through the thick barrier of federal,

state, and local laws, all of which were designed to prevent exactly that sort

of entrepreneurship. Check out our White Whiskey

pages for some (now long outdated) stories about a few of those pioneers.

Then around the turn of the century -- that's this

century, mind you, the year 2003 to be exact -- Bill Owens and Penn Jensen started up the

American Distilling Institute in Northern California and people who once had

only dreamed of operating a whiskey still could meet with one another and

exchange ideas. The explosion of micro-, craft-, artisan-, or whatever

distilleries has been incredible. As of 2012 there were over 250 small producers

of American spirit, at one time mostly producing unaged vodka and gin but now

more are making whiskey. And that's not counting the blenders and bottlers who

select choice barrels from established distillers and mix them up to produce

their own distinctive products. We have tried to cover some of them, but with

distilleries in nearly every state and more starting up each week, there's no

way to keep up.

Most of these craft distilleries are very small shops, often built by a distiller whose goal is to produce the one single whiskey which will be considered the finest ever crafted. In the pursuit of that dream, which requires years of daily production before the first dollar of return is realized, s/he will make vodka, gin, absinthe, unaged rum and whiskey... whatever can be sold quickly. Or s/he may simply buy aged whiskey from another supplier (in bulk, that is; not by carefully selecting barrels) and bottle that to establish a brand until their own product is ready for market... if it ever is.

Typically, artisan-distillers value the smallness of their operation, and like to maintain somewhat of a rebel image. They are offering a boutique alternative to those Big Guys in Kentucky. With a few exceptions, they are not interested in being associated with established bourbon tourism organizations. The rich history of the Beams, the Browns, and the Van Winkles is old news to them (and probably most of their potential customers as well). The very real heritage of Kentucky whiskey is, if anything, an obstacle to most of their marketing ideas.

Enter a new riff. In fact, enter the New Riff Distilling Company in Newport, Kentucky. New Riff is a craft distillery with origins very different from most (if not all) of the others. And a distillery which is extremely conscious, and proud, of its Kentucky heritage.

First of all, it's located in Newport, which is not in the bluegrass part of the

state, like most of the others, but sits up at the very northern edge, across

the Ohio River from Cincinnati.

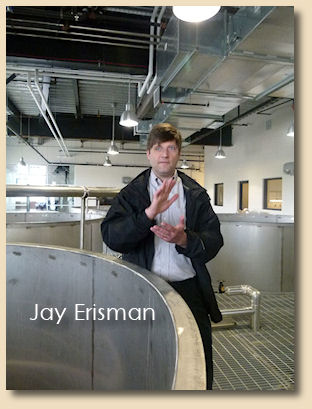

As production manager for distilling Jay Erisman

points out, this area was once very rich in American whiskey history. Before

(and arguably during) Prohibition, Cincinnati was the largest distribution

center for beverage alcohol in the United States. Some of that whiskey was

distilled in and around Cincinnati in Ohio and Indiana, but most was produced by

distilleries in Kentucky. And among those were several in the Newport area.

There is a well-known Country & Western nightclub in Wilder, an area adjacent to

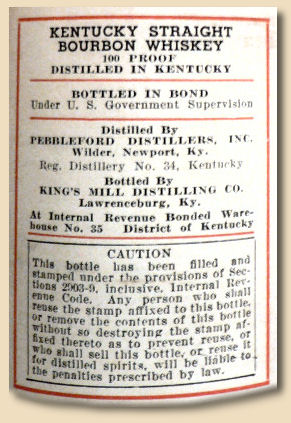

Newport which is housed in a building that was once such a distillery, Pebbleford (RD 34 KY). We have in our collection a bottle of fine bourbon

produced there in 1946. Even earlier, it is believed, much of the whiskey that

would one day be known as Bourbon arrived downriver at Louisville from ports

such Maysville and Newport. Erisman is proud of Kentucky's role in American

whiskey, especially Northern Kentucky. And his vision is to see New Riff join,

rather than avoid, other established Kentucky distillers in promoting tourism

and appreciation of Kentucky whiskey.

As production manager for distilling Jay Erisman

points out, this area was once very rich in American whiskey history. Before

(and arguably during) Prohibition, Cincinnati was the largest distribution

center for beverage alcohol in the United States. Some of that whiskey was

distilled in and around Cincinnati in Ohio and Indiana, but most was produced by

distilleries in Kentucky. And among those were several in the Newport area.

There is a well-known Country & Western nightclub in Wilder, an area adjacent to

Newport which is housed in a building that was once such a distillery, Pebbleford (RD 34 KY). We have in our collection a bottle of fine bourbon

produced there in 1946. Even earlier, it is believed, much of the whiskey that

would one day be known as Bourbon arrived downriver at Louisville from ports

such Maysville and Newport. Erisman is proud of Kentucky's role in American

whiskey, especially Northern Kentucky. And his vision is to see New Riff join,

rather than avoid, other established Kentucky distillers in promoting tourism

and appreciation of Kentucky whiskey.

There's another factor that sets New Riff apart from other new distilleries, and that's its business origins. To understand that, you need to consider just how groundbreaking an event its groundbreaking ceremony on July 19, 2012 was. You see, there's a thing called the "three-tier system". This method of alcohol distribution control was established, and set in stone, by the federal government as part of implementing the 21st Amendment, which marked the end of The Great Experiment of Prohibition. The three-tier system consists of producers, distributors, and retailers. It is set up such that alcohol producers can sell their products only to wholesale distributors. The distributors are allowed to sell only to retailers (who must purchase only from the distributors), and then the retailers, and only retailers, may sell to consumers.

This system has been one of the hardest for small artisan distillers to overcome, because they have little access to the handful of large distributors and they depend on being able to sell directly. The early independent small distilleries were often established in "control" states, where there was state-operated distribution, because all the effort to overcome the hurdles to make and sell their product at all included getting the state distribution as part of the process. A chief factor in the proliferation of small distilleries is the recent loosening of those restrictions.

But that applies to distilleries wanting to sell their own product onsite. The

case of New Riff is very different. The idea for establishing the distillery

came to the two gentlemen most closely responsible for New Riff a few years

back. Ken Lewis is the founder of The Party Source, a very large liquor,

wine, beer, and party-supply retailer in Bellevue, Kentucky. Ken is proud of his

store, one of the best-known in the United States, not just locally, and one of

his most prized assets has been, for more years than you might imagine to look

at him, his spirits manager, Jay Erisman.

Jay began working at The Party Source

as a young man with a mission. His mission was to obtain a catalog of single

malt scotch such as Kentucky (and certainly Cincinnati) had never before seen. A

serious student of all sorts of spirits (and wines, and beers), Jay is the sort

of fellow who learns about Bruichladdich single malt by traveling to Islay,

Scotland and spending a day or two talking with the folks who make it.

Jay began working at The Party Source

as a young man with a mission. His mission was to obtain a catalog of single

malt scotch such as Kentucky (and certainly Cincinnati) had never before seen. A

serious student of all sorts of spirits (and wines, and beers), Jay is the sort

of fellow who learns about Bruichladdich single malt by traveling to Islay,

Scotland and spending a day or two talking with the folks who make it.

And he feels the same way about American whiskey, as well. He was among the first retailers to purchase individual barrels of bourbon for sale in his store. Not the barrels themselves, of course; you can't do that. Three-tier system requires that the producer deliver the whiskey already bottled. So you get the whiskey that was in that barrel (or those barrels), with your store's name nicely pasted on a sticker or perhaps printed on the label. Not that having a store brand, or a "specially bottled for..." label is anything new; retailers, and even hotels and restaurants, have been doing that since the 1800s. What made Erisman's riff on that something different was that he actually went out to the distillery and worked with the warehouse manager to make his selections. Sampling from several barrels, he selected only the finest as he tasted it. In that respect he became his own bottler, not unlike Van Winkle or Smooth Ambler. It's one thing for a retail store or restaurant to purchase production whiskey and have their name printed on the label; it's really pushing the envelope a bit to create your own unique product... as a retailer. But that's just the way he does it.

Or did it. In December of last year (2013), some of us received an email from Jay that, effective January 1, 2014 he would no longer be associated, directly at least, to The Party Source. This was his announcement that he has taken on the position of Production Manager at New Riff Distilling.

He's not the only one leaving The Party Source, either. Ken Lewis, the owner and founder of the store, has also left to assume his responsibilities as owner of New Riff Distilling. It's that old three-tier system again. "Ya say ya wanna run a distillery, boy? Well ya gotta give up the retail store".

Lewis didn't just "give up" the store though; he sold it to his employees.

Really!

All 51 full-time and 18 part-time employees. Coincident with his transfer to president of New Riff Distilling, Lewis announced the creation of the employee stock ownership plan. In a press release, he said "It’s been my dream all along to turn this company over to my employees who helped make the Party Source not just the largest beverage and alcohol store in the U.S., but one of the most successful and cutting edge operations as well".

So you can just stick that in your three-tier system, Uncle Sam!

Not that Lewis will be very far away from the store. Neither will Erisman. The New Riff Distillery (and the Ei8ht Ball Brewing Company in the same building) is located literally in the parking lot of The Party Source. That's not as strange as it may seem. For one thing, the parking lot is huge. And for another, the distillery isn't really in the parking lot; it's built on land that didn't exist before.

What's that, you say? Just where is this distillery, anyway? Well, like most other things about this enterprise, it's very location is a new riff.

The Party Source is in the town of Bellevue, Kentucky, a

quaint little river town just east of Newport.

It lies right on the edge of town, alongside the flood levee.

Well, at least the part of The Party Source that existed

before the 30,000 square foot expansion that is part of the distillery-building

project is there. But, while the property line that distinguishes Bellevue from

Newport remains where it has always been, the levee bank does not. Part of the

overall construction plan involved replacing the earthen levee with a more

modern concrete flood wall. The project provides an additional two and half

acres of land, some of which has been used for the store expansion and the

rest for the distillery and additional parking. The kicker is that, while all of

the distillery is located in Newport (and its tax district), The (expanded)

Party Source is now located in both communities. Not sure just how

that works out.

Well, at least the part of The Party Source that existed

before the 30,000 square foot expansion that is part of the distillery-building

project is there. But, while the property line that distinguishes Bellevue from

Newport remains where it has always been, the levee bank does not. Part of the

overall construction plan involved replacing the earthen levee with a more

modern concrete flood wall. The project provides an additional two and half

acres of land, some of which has been used for the store expansion and the

rest for the distillery and additional parking. The kicker is that, while all of

the distillery is located in Newport (and its tax district), The (expanded)

Party Source is now located in both communities. Not sure just how

that works out.

Okay, so much for how different this new riff on distilling is, how is it like its contemporaries?

Well, of course there's no product yet. As of this writing (spring of 2014) everything is in place and ready to mash up some grain, fire up the ol' (new?) still, and let 'er rip. Uh, make that "let 'er riff". That is scheduled to happen at the end of April. The first whiskey made will be a bourbon, and Erisman expects it to age for four years... at least. And that's in standard-capacity 53 gallon barrels, too, about 12 barrels a day.

That opinion is echoed by master distiller Larry Ebersold, another jewel in New Riff's treasure chest. Highly respected throughout the industry, Ebersold was master distiller at Lawrenceburg, Indiana for twenty years, beginning when that distillery was owned by Seagrams. He is credited with producing some of the finest bourbon and rye whiskey ever distilled, much of which has provided the backbone for well-known independent bottlers (not to mention a lot of "distillers" whose products contain only LDI/MGP whiskey). Larry Ebersold understands how to use the equipment to produce whatever custom flavor profile you want to achieve.

And what sort of equipment, you ask? New Riff has a column still,

built by Vendome in Louisville. It is 24 inches in diameter. Most of the "big

boys'" stills are twice that or more. And some are made of stainless steel; New

Riff's is all-copper. So's the doubler, a kind of pot still that is used for the

second distillation. And so's the REAL pot still, a wonderful contraption of the

sort that many small distillers employ because they're small, simple, and

relatively inexpensive. This one isn't.

It has more valves, adjustments, and

reflux redirectors than a baritone saxophone, and Larry Ebersold is teaching

distiller Brian Sprance just how

to play it:

It has more valves, adjustments, and

reflux redirectors than a baritone saxophone, and Larry Ebersold is teaching

distiller Brian Sprance just how

to play it:

You want Stan Getz? Okay.

Clarence Clemons? Yup.

Charlie Parker? The bird can fly.

Lisa Simpson? Uh, well, sure; all right, if that's what you want, we can do it

that way, too.

Most of the Big Boys like to play down their use of column stills. The image their marketing departments like to project has long been that of a single, wise-if-not-particularly-well-educated distiller operating a small copper pot still.

While whittling a toy boat for his kid, if possible.

The giant, industrial-grade column stills are not spotlighted; some are kept out of public view altogether.

New Riff's gleaming copper 45-foot tall still is spotlighted in a glass tower built right up front and made especially to show it off to the world. You don't even have to enter the distillery to see it. We know of only one other such distillery: McKenzie's Finger Lakes Distillery in New York is also designed that way.

There is one aspect of New Riff that bears watching closely, and that will be the reaction (and that's exactly the term I mean) from the pundits and the spirits press. Especially those who remain emotionally tied to the old stereotypes about American whiskey. The ones who equate all whiskey with Bourbon, all Bourbon with Kentucky, and all of Kentucky with back-country agriculture. The people of New Riff call it that because they see their product as a "new riff" on an old tradition. Ken Lewis says, "we like to call it Kentucky URBAN Whiskey. A new taste on the long standing tradition of bourbon."

Today we are among a few folks invited to a pre-opening tour of the facility (which also includes extensive spaces for cooking classes, demonstrations, tastings, meetings, and banquets - including an outdoor riverview terrace). This is a dress-rehearsal for chief tour guide David Miller, and he brings the sort of knowledge and self-assurance one would expect (but often fail) to find in seasoned guides with years under their belt. Erisman points out that a contributing factor might be that Miller has been a star sales representative for The Party Source for several years and really does know his stuff. If David is an example of the level of training expected of the tour guides, this is going to be a very good place for folks to learn about whiskey-making in Kentucky.

During the tour, Miller also introduces us to Brian Sprance, New Riff's hands-on distiller who is the man who actually turns the knobs and works the valves. Brian is finishing up the details for the "launch" later this month, and he really is like a rocket technician, checking each valve and connection. I'll bet this place will be like the Houston Space Center when it's time to fire up the stills.

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2014 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|