American

Whiskey:

White Whiskey: Legal

Moonshine

FOR SOME PEOPLE, fine whiskey means Kentucky Bourbon. Once upon a time it might have been Pennsylvania or Maryland Rye. Of course, what they mean by "fine whiskey" is barrel-aged bourbon or rye which has acquired the caramel and vanilla flavors that result from years of storage in never-used-before, charred oak barrels. Whiskey without those flavors is sometimes characterized as raw, crude, and evil-tasting; a product suitable only for unsophisticated tastes, or perhaps as a novelty.

Now, to some of us who enjoy fresh-made whiskey, that

characterization seems a little bit like suggesting that fresh peaches lack the delicate balance

and flavor nuances of the more sophisticated canned peaches.

In the dim past, this was the whiskey that farmers made from their crops

and sold to riverfront whiskey merchants. In Pennsylvania and Maryland,

the farmers were mainly German-Swiss (Pennsylvania Dutch) rye growers; in

Virginia (which included Kentucky then) they were mostly Scots-Irish corn

(maize) growers.

But the rye farmers didn't make the Monongahela sipped in Baltimore and

Philadelphia taverns.

And the corn farmers didn't make Bourbon.

No matter who wrote that book you read, or what that 275-pound bartender with the nasty look on his face

tells you.

Even if it meets all other criteria, whiskey cannot be called "bourbon"

until it's been stored in a new, charred, oak barrel. Even if the old

frontier farmers had a new, charred, oak barrel, it's not likely that

they'd store whiskey in it. Barrel-aged whiskey was the realm of the

whiskey merchant, not the farmer-distiller.

And then there's White Lightnin'.

Many people believe that fresh whiskey and moonshine are the same thing.

This has an interesting effect on the public perception of this spirit,

because the sense of "naughtiness" that view imparts adds both a tingle of

excitement to the experience of drinking it, and a tendency for people to

distance themselves from association with it.

There is such a thing as moonshine, of course. In fact, there might

be nearly as much real 'shine being made, sold, and drunk than there is legal fresh

whiskey, at least in the states where it's most prevalent. In the movies, magazines, and novels, moonshine is nearly always

portrayed as either a horrible hillbilly atrocity (made crudely, of

course, because "everybody knows" mountain people aren't supposed to be intelligent or

sophisticated enough to make a refined product), or as prohibition bathtub

gin made by evil criminals with nothing better to do than blinding and

killing unsuspecting flapper-girlies and collegians. Although there are plenty of

examples to support either of these characterizations, most fresh-made

whiskey falls into two somewhat more benign categories.

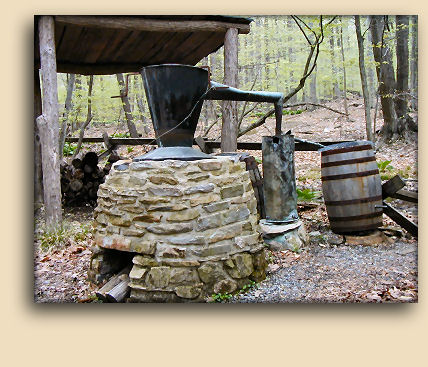

First we have the moonshine commonly known as white lightnin', or popskull,

or mule-kick, or something along those lines. It's not really "whiskey" at

all, being distilled from a "mash" of fermented sugar-water with perhaps a

handful or two of cornmeal tossed in for flavor (and so that everyone can

pretend there is some relationship to corn in the product). It is

typically stored in 1 gallon plastic milk jugs.

It is also NOT typically consumed by the distiller or anyone he knows.

This is the 'shine you might obtain at a keg-party, in illegal

"shot-houses" set up in people's homes, or from a "blind-tiger", which is

a setup by which the money for the purchase is left in an unattended

location and the 'shine is later picked up at that (or another) location,

all without the buyer ever seeing the seller. And once you get out of

Elliot Ness' Chicago and up into the hills, people are much less likely to

confuse their local moonshiner with the likes of Al Capone. According to an interview with Johnston County (North Carolina)

District Attorney Tom Lock (who defended several moonshiners before he was

elected to run the office that prosecutes them), "In the scheme of things,

it's not treated all that seriously. It's only a misdemeanor. We certainly

can't condone it and we can't ignore it, but I don't think the prosecution

of non-tax-paid liquor in and of itself is a high priority in the minds of

most citizens." In North Carolina, most charges regarding the manufacture

and sale of liquor on which tax is not paid are misdemeanors, punishable

by fines ranging from $50 to $500. A raid which actually succeeds in

capturing the distiller, his still, his stock, and his customer list (a

rare occurrence) would result in four charges: possession of non-tax-paid

liquor; possession with the intent to sell such liquor; possession of

equipment to manufacture it; and manufacturing it. Of those, the most

serious charge is manufacturing. Under state law, a second offense can be

prosecuted as a felony, although it is the lowest-grade felony possible

and generally would bring probation or a very short jail term. Almost

always, the defendant will plead guilty to one or two of the charges, pay

a fine and get the others dismissed.

punishable

by fines ranging from $50 to $500. A raid which actually succeeds in

capturing the distiller, his still, his stock, and his customer list (a

rare occurrence) would result in four charges: possession of non-tax-paid

liquor; possession with the intent to sell such liquor; possession of

equipment to manufacture it; and manufacturing it. Of those, the most

serious charge is manufacturing. Under state law, a second offense can be

prosecuted as a felony, although it is the lowest-grade felony possible

and generally would bring probation or a very short jail term. Almost

always, the defendant will plead guilty to one or two of the charges, pay

a fine and get the others dismissed.

Other moonshiners, and often the same ones who make 'lightnin', make a

different kind of 'shine in their stills. This is real honest-to-Pete corn

whiskey (or rye whiskey) This form of fresh whiskey, called "corn whiskey"

or "rye whiskey", "white whiskey", or "white dog", uses little if any

Dixie Crystal Pure Cane Sugar, and obtains its sugars from the enzymes

found in malted corn or barley. This is the whiskey the distillers drink

themselves and serve to friends. Unless you're family or a neighbor, the

only way you're going to taste this whiskey is to get yourself invited to

the daughter's wedding. That's because, unlike bread, or candles, or apple

pies, or furniture, it's illegal to make whiskey at home non-commercially

in the United States. The law sees no difference between a distiller of

whiskey for gifts or personal consumption and an unlicensed commercial

distiller. Still meeting its original mandate to eliminate a competing

monetary basis, the law forbids any distilling (or even possession) of

beverage alcohol whatever, except for large, licensed, regulated

commercial distilleries.

But we're not concerned here with whiskey you can't legally buy or

distillers you can't visit without "gittin' yore haid blowed off". What

separates the distillers of fresh whiskey we'll be visiting here from

their moonshinin', bootleggin' cousins is that they're legally licensed to

produce, bottle, sell, and pay taxes on whiskey marketed through regular

retail channels. What separates their operations from the other whiskey

distilleries we've been visiting is that these distillers make fresh,

white whiskey.

And within the past few years, some brave souls have gone to the

considerable expense and trouble to obtain official sanction to produce

and sell it legally.

In

2005, Linda and John visited the sites of three such distillers. One is

Payton Fireman, a young lawyer and entrepreneur in Morgantown, West

Virginia, whose West Virginia Distillery Company produces Mountain

Moonshine, a perfectly legal unaged white spirit whiskey made from a

bourbon-recipe base. Another is Rodney Facemire, another West Virginian,

who was the owner and winemaker at Kirkwood Winery in beautiful

Summersville, West Virginia for many years (and still is), before deciding

to concentrate on his Isaiah Morgan Distillery operation. Rodney not only

makes corn liquor, but he is one of only two legal bottlers of unaged rye

whiskey in the world (actually the only one, since Old Potrero, the brand

Fritz Maytag produces in San Francisco, California is no longer offered

completely unaged). Just outside of Culpeper, Virginia, we meet Chuck and

Jeanette Miller whose Belmont Farms of Virginia produces Virginia

Lightning and Copper Fox from corn grown on their own farm and distilled

in their big old 1930's moonshine still. And they sell it, quite legally,

through the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control stores.

In

2005, Linda and John visited the sites of three such distillers. One is

Payton Fireman, a young lawyer and entrepreneur in Morgantown, West

Virginia, whose West Virginia Distillery Company produces Mountain

Moonshine, a perfectly legal unaged white spirit whiskey made from a

bourbon-recipe base. Another is Rodney Facemire, another West Virginian,

who was the owner and winemaker at Kirkwood Winery in beautiful

Summersville, West Virginia for many years (and still is), before deciding

to concentrate on his Isaiah Morgan Distillery operation. Rodney not only

makes corn liquor, but he is one of only two legal bottlers of unaged rye

whiskey in the world (actually the only one, since Old Potrero, the brand

Fritz Maytag produces in San Francisco, California is no longer offered

completely unaged). Just outside of Culpeper, Virginia, we meet Chuck and

Jeanette Miller whose Belmont Farms of Virginia produces Virginia

Lightning and Copper Fox from corn grown on their own farm and distilled

in their big old 1930's moonshine still. And they sell it, quite legally,

through the Virginia Alcoholic Beverage Control stores.

In 2011, they visited another handful of (legal) white whiskey distillers. As the laws of the individual states begin catching up to the federal 21st Amendment, there will be more and more small, craft/artisan distillers, and because you can't make old spirits or new spirits without starting with white spirits, we will almost certainly be seeing more and more of them. It's impossible to keep up, and we don't intend to try, but each of these distillers offers an important experience in both the way spirits are made and they way America was made. You should visit them, too, if you get a chance. They'd love to see you.

Corn whiskey (and unaged rye whiskey as well) is a very different spirit from aged bourbon or rye, and not everyone likes the taste of their whiskey raw. But for those who do enjoy it, and for those who want to understand the relationship between the product of the corn or rye farmer and the spirit we know as bourbon or rye whiskey, the following explorations are vital to understand.

White Whiskey: Yes, Virginia (and West Virginia, Tennessee, and even

Kentucky),

there is legal, hand-crafted hooch

| Belmont Farms of Virginia | Culpeper, Virginia | Chuck and Jeanette Miller have

been making Virginia Lightning and

Copper Fox here since 1989. Now they're

being featured on public television and The History Channel and gearing up

for visiting tourists. |

|

| Corsair Artisan Distillery | Nashville, Tennessee and Bowling Green, Kentucky |

Darek Bell and Andrew Webber

produce very sophisticated spirits, the type sought by the top bartenders

and mixologists in the country. They make them from white spirits they

distill in Nashville, one of which is a white dog rye whiskey they bottle by

itself as Wry Moon. |

|

| Isaiah Morgan Distillery | Summersville, West Virginia | Rodney Facemire's distillery is (a very

small) part of his Kirkwood Winery. He makes white brandy (grappa),

Southern Moon

white corn liquor, and unaged Isaiah

Morgan Rye Whiskey. |

|

| M. B. Roland Distillery | Pembroke, Kentucky | Paul Tomaszewski and his wife

Merry Beth (nee Roland), for whom the distillery is named distill

White Dog, Black Dog,

and True Kentucky 'Shine from locally-grown

corn, along with several other products made from white whiskey. They make

make aged whiskey, as well. |

|

| Prichard's Distillery | Kelso, Tennessee | Phil Prichard is a craftsman and

an experimenter, and a respecter of no one's limitations on what can be made

with a good still and some Moxie. His interests tend toward rum, but he

enjoys making whiskey. Especially controversial whiskey. His

Lincoln County Lightning calls into question

all the "expert" definitions of Tennessee whiskey. |

|

| West Virginia Distilling Co. | Morgantown, West Virginia | Payton Fireman makes Mountain Moonshine spirit whiskey and Mountain Moonshine Old Oak Recipe in Bo McDaniel's old auto repair garage. |

|

|

Story and original photography

copyright © 2005 by Linda Lipman and John Lipman. |