American Whiskey

August

25, 2012 |

|

Johnny Appleseed... and

Cornseed, Ryeseed, Maltseed, etc.

A famous Pennsylvania still moves to Kentucky and then Ohio.

![]()

IN ANOTHER ARTICLE on this website we noted "It wasn't always 'bourbon', y'know".

That was the introduction to the story of American rye whiskey. But even before

rye whiskey, as well as during it's hey-day in the 18th and early 19th centuries, America's OTHER

spirit of choice was apple brandy, also known as "applejack". We're all pretty

familiar with that name; from children's breakfast cereal to apple wine, to

cocktails made with apple juice and Tennessee whiskey, lots of things have been

called applejack.

And of course, we have the (mostly Disney-fied) legend of

Johnny Appleseed, planting the American frontier with apple trees. Johnny

Appleseed was not just a made-up legend, however, although he wasn't the Tom

Sawyeresque boy in leather overalls pictured in most of our minds.

And of course, we have the (mostly Disney-fied) legend of

Johnny Appleseed, planting the American frontier with apple trees. Johnny

Appleseed was not just a made-up legend, however, although he wasn't the Tom

Sawyeresque boy in leather overalls pictured in most of our minds.

There really was a

man known as Johnny Appleseed, who was more properly named John Chapman. He

lived from 1774 to 1845 and was a legend even in his own time. A religious man

and a wandering missionary, Chapman is credited with planting apple trees all over

what was the north and west at that time -- New England, New York, Pennsylvania,

Indiana, and Ohio especially. He didn't plant orchards; he planted nurseries and

then sold the seedlings to settlers who wanted to establish orchards (one way of

obtaining land permits). There are no records of how many apple trees Chapman

planted, but he left over 1,200 acres of apple tree nurseries to his sister at

his death.

There really was a

man known as Johnny Appleseed, who was more properly named John Chapman. He

lived from 1774 to 1845 and was a legend even in his own time. A religious man

and a wandering missionary, Chapman is credited with planting apple trees all over

what was the north and west at that time -- New England, New York, Pennsylvania,

Indiana, and Ohio especially. He didn't plant orchards; he planted nurseries and

then sold the seedlings to settlers who wanted to establish orchards (one way of

obtaining land permits). There are no records of how many apple trees Chapman

planted, but he left over 1,200 acres of apple tree nurseries to his sister at

his death.

The apple trees that grew from Chapman's seedlings did not bear edible fruit. That

popular image of

mop-haired Johnny Appleseed biting into a nice, juicy apple is totally

fictitious. According to author/activist Michael Pollan, Johnny Appleseed was

morally against grafting and he used only wild apples for his seedlings. The

resultant apples were inedible and could be used only for cider: "Really,"

wrote Pollan, "what

Johnny Appleseed was doing and the reason he was welcome in every cabin in Ohio

and Indiana was he was bringing the gift of alcohol to the frontier. He was our

American Dionysus."...

The tradition of distilling applejack is very much a part of Ohio, and one major

proponent of that tradition is Tom Herbruck. Tom, who makes his home on a farm near Chagrin

Falls, in the northeast part of the state, began producing applejack in the old,

traditional way back around the end of the 1990s, using a 50-gallon pot still he'd bought several years

earlier. Those were the days when any legal production of liquor was the result

of months and years of petitioning and succeeding in getting laws changed to a

more rational interpretation of the 21st Amendment (the repeal of National

Prohibition). Many of those late '90s

pioneers made corn whiskey (see our pages on White Whiskey), but the distillery

that would become known as "Tom's Foolery" produced true applejack, and that's

all.

At least that WAS all until this century, when Herbruck found himself with an

opportunity of a lifetime for a young distiller. He was able to purchase a

small, one-barrel-a-day capacity pot still from David Beam (of THOSE Beams). This

still has a unique place in the history of American whiskey. It was originally

built by the Vendome copper company in 1976 and installed in what was then

America's oldest operating distillery, in the little town of Schaefferstown,

Pennsylvania. The actual name of the distillery was Pennco, and the main still

there in the 1970s was a four-story column still, similar to those used by

nearly everyone in the industry. But most people think of a different name for

the place. That's because there was a retail store on the property,

which was

(at least officially) not owned by Pennco. It was called Michters Jug House, and

sold souvenir "jugs" of whiskey to tourists. The brand later grew large enough

to warrant normal glass bottles, as well as ceramic decanters, and national (or

at least regional) distribution. Tourism was still an important feature of

Michters' operations, though, and as part of the Bicentennial fever of 1976, they installed

this tiny pot still at the Jug House to show tourists how whiskey was made.

David Beam set up the still back then, and Dick Stoll, the master distiller for Pennco,

operated the little pot still for only a few years before Pennco (and Michters)

closed its doors. The still, along with all the supporting equipment, was

purchased by David Beam , dismantled,

and taken to Bardstown, Kentucky, where it remained in storage for many years.

For more about that, see the photos on our page about Michters, where we visited

David Beam and saw the still.

which was

(at least officially) not owned by Pennco. It was called Michters Jug House, and

sold souvenir "jugs" of whiskey to tourists. The brand later grew large enough

to warrant normal glass bottles, as well as ceramic decanters, and national (or

at least regional) distribution. Tourism was still an important feature of

Michters' operations, though, and as part of the Bicentennial fever of 1976, they installed

this tiny pot still at the Jug House to show tourists how whiskey was made.

David Beam set up the still back then, and Dick Stoll, the master distiller for Pennco,

operated the little pot still for only a few years before Pennco (and Michters)

closed its doors. The still, along with all the supporting equipment, was

purchased by David Beam , dismantled,

and taken to Bardstown, Kentucky, where it remained in storage for many years.

For more about that, see the photos on our page about Michters, where we visited

David Beam and saw the still.

In 2011, Tom and Lianne Herbruck purchased the still and had it shipped to

Chagrin Falls, Ohio. Along with the still they got both David Beam and Dick

Stoll to set it up and show them how to operate it. The first product from the

still was applejack, but almost immediately Tom began mashing bourbon and rye

whiskey and distilling that at the same one-53-gallon-barrel-a-day rate as

before.

We visited the Herbrucks in August of 2012. The distillery, which is not really

open to the public (although the new facility they're building just up the road

will be open in 2016 and will offer tours), is located in the barn of their

lovely farmhouse. In fact, the upper floor loft was once the playroom for their

little girls and their crayon-colored drawings still adorn the walls.

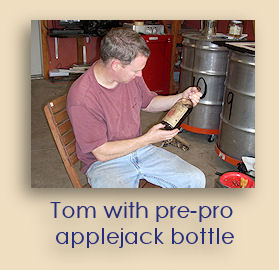

We brought with us an unopened bottle of pre-prohibition applejack dating from right around 1900 and we proceeded to open and taste it with Tom. We were all surprised that it was very little like what we think of as applejack today, tasting thicker and sweeter, more like an oak-y apple liqueur.

We had hoped to obtain a bottle of Tom's applejack for our own collection, but there was none left, except what was still aging. At the time he was concentrating only on producing bourbon and rye, and the oldest of that had aged only a few months. He was distilling various mash bills, and in fact had just completed one such distillation that very morning. Magnanimously, Tom allowed John the "honor" of cleaning out the still, while Linda and Lianne looked on (trying not to giggle too loudly). Later we tasted samples from some of Tom's ornately painted barrels. We enjoyed several samples and anxiously awaited the two or so years it would take before full bottled retail product would become available.

Well, that was then, and this is now.

As we

write this today (May 2015) bottles of Tom's Foolery Straight Bourbon (and rye,

too) can be found on store shelves all over Ohio and other states. For those who cherish the heritage of

American whiskey this would be a must to try. For those who are especially

enamored of anything Michter, consider this -- What is in that bottle of Tom's

Foolery whiskey is a product produced on the original Michter Jug House still,

by the student of both David Beam and Dick Stoll. It is as close to the original

Michters whiskey as you will ever taste. Oh, and for those who just enjoy good

craft-distilled bourbon, well this sure hits that point, too.

As we

write this today (May 2015) bottles of Tom's Foolery Straight Bourbon (and rye,

too) can be found on store shelves all over Ohio and other states. For those who cherish the heritage of

American whiskey this would be a must to try. For those who are especially

enamored of anything Michter, consider this -- What is in that bottle of Tom's

Foolery whiskey is a product produced on the original Michter Jug House still,

by the student of both David Beam and Dick Stoll. It is as close to the original

Michters whiskey as you will ever taste. Oh, and for those who just enjoy good

craft-distilled bourbon, well this sure hits that point, too.

On their website (www.tomsfoolery.com), which Lianne publishes, you can access a complete database of every barrel they've made, including those that have been bottled and those still maturing. The database gives minute detail, including the variety of corn, rye, barley, the mashing process, barreling proof, even who made the barrel and what degree of char. In this age of "craft distillers" re-bottling sourced product as their own, as far as we know, no other craft whiskey distiller -- and certainly no major distillery -- publishes this information. For a connoisseur, this is nerd-heaven. About the only thing they don't give you is the corn farmer's daughter's phone number.

![]()

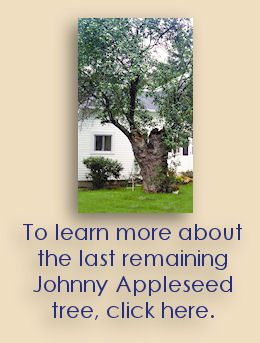

... Now, according to the Smithsonian Institute, the last remaining Chapman-derived apple tree is still living (as of 2014) on a farm in Nova, Ohio, about 70 miles southwest of Chagrin Falls. Some historians dismiss that belief based on the fact that it is a Rambo apple tree and Rambo apples, while an antiquated variety that was known in Chapman's time, were grafted plants and Chapman did not use grafted plants. For those of us who (attempt) to weave our way through American whiskey's history, such comes as no real surprise. Suffice it to say that if you find yourself in Nova, Ohio, standing in front of the "last Johnny Appleseed tree", you might want to allow yourself a moment to contemplate the man to whom it is attributed, without doubt or shame. Most of American whiskey's sacred spots are no more valid, nor any less valid, a memorial.

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2015 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|