|

American

Spirits

March 31,

2011

Woodford Reserve

Distillery

Versailles,

Kentucky

Once known as

Labrot

& Graham

And before that, Jas. E. Pepper

And before that, Oscar Pepper

And even before that, Elijah Pepper

(Oscar's dad) |

|

|

The really, truly oldest Kentucky

bourbon distillery.

ELIJAH PEPPER came to Kentucky in the late 1790s, from Virginia.

Some say his departure may have been hastened by some troubles there, which may

also have caused him to change his name from the original Culpeper, a

distinguished family from whom he is said to have descended. Others believe that

if someone were really "on the lam", he might have considered choosing

a less obvious name than "Pepper". But that's a lot of how trying to learn about

whiskey origins works -- ya pays yer dime and ya makes yer choice.

Whatever...

Elijah married well, his wife Sarah was from the distinguished

O'Bannon family and her brother John became Elijah's partner. They owned most of

the land now known as Versailles (which is pronounced "Vur-Sails" in Kentucky, not "Vair-Saigh"

like in France), and they distilled whiskey at various locations for about 15 years before ending up at

this spot alongside Glenn's Creek in 1812. The distillery they built here has had its ups

and downs -- by which we mean, built ups and burnt (or collapsed) downs -- over

the years, but there is still a distillery here, and some of the original

buildings are still standing and in use. Except for during Prohibition and

twenty-some years in the '70s and '80s, it has been in continuous use as a

distillery for nearly two hundred years. And it's still putting

out fine bourbon.

Very fine bourbon.

And very unique bourbon at that.

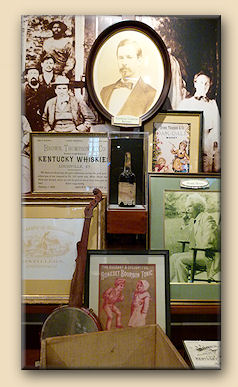

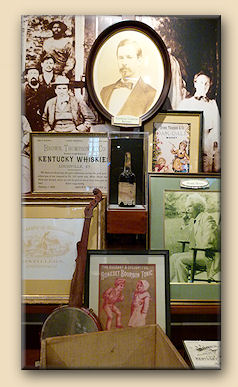

Elijah died in 1831. Most of the "glory" part of this distillery

came at the hands of Elijah's son, Oscar. Oscar Pepper had the good sense (or

good luck) to hire a Scottish chemist and medical doctor, James Crow, as his

distiller. Dr. Crow came to the United States almost immediately after obtaining

his degree (M.D., Edinburgh University 1822) and under somewhat shadowy

circumstances (there are stories involving skipped debts and an abandoned wife

and children). Seeking employment, he went to work for a distillery in or near

Philadelphia. In 1835 he moved to Kentucky and obtained employment as Oscar

Pepper's master distiller. For the next 29 years, Dr. Crow polished and adjusted

the processes he used, and (more importantly) documented everything in a

way that anyone with scientific training could understand and duplicate. Because

he published his methods, Dr. Crow is credited with the idea of using spent mash

-- after distillation -- to adjust the acidity of new mash, and of measuring and

recording distillery processes, using instruments such as the hydrometer, to

ensure continuity in production. At a time long before the concept of

microorganisms existed in the world of food and beverage production, Dr. Crow

was introducing sanitation practices to his distillery.

He produced what soon came to be recognized as the finest whiskey

ever made. Not just in Woodford County, Kentucky, either.

No,

Oscar Pepper's "Old Crow" whiskey was the personal choice of such as Andrew

Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, Henry Clay, William Henry Harrison, and Daniel

Webster.

No,

Oscar Pepper's "Old Crow" whiskey was the personal choice of such as Andrew

Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, Henry Clay, William Henry Harrison, and Daniel

Webster.

Just when Dr. Crow left Oscar Pepper's distillery is unclear, but

at some point he moved to the Johnson distillery just up the creek, which later

became the Old Taylor distillery, operated by Edmund Taylor. He took the "Old Crow" brand with him and

worked there until he died in 1856. Besides being an owner, partner, or investor

in several distilleries in Woodford and Franklin counties (see our

Ghosts of Distilleries Past

page for more details), Edmond Taylor was also involved with politicians, at both

local and higher levels. Among those was his close personal friend, John G.

Carlisle -- who, besides being the United States' Secretary of the Treasury

(that is, the federal governing authority for the distilling industry) was also the

author of the 1897 Federal "Bottled in Bond" Act. That particular piece of legislation

became the defining authority for what would come to be called "Straight Whiskey", and

it has remained so, through the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, the medicinal whiskey laws of

Prohibition, the post-Repeal Code of Federal Regulations, and right on up to

today.

When Carlisle, who rally cared about Kentucky bourbon, was drafting this act, he was well aware that the

requirements and restrictions would become the model upon which the best

whiskies would be defined, and he wanted that whiskey be the best quality

currently available. What he chose as a model was, not surprisingly, the one provided to him by his

respected friend Edmund Taylor. And those

specifications were none other than the formulas carefully documented so long

ago by Dr. James C. Crow.

And thus, and for good reason, did Dr. Crow's formulas and

methods become the basis for our concept of what straight bourbon whiskey is,

and that is also why Dr. Crow can rightfully be called "the father of bourbon

whiskey".

And the production methods of that seminal bourbon whiskey were

first developed and recorded at this very distillery (or at least the distillery

that existed at this location, and one a lot more like the original than any

other in existence today).

Not that Woodford Reserve's bourbon is an attempt to duplicate

Dr. Crow's formula. Far from it.

For one thing, the Brown-Forman company were already making two

very successful whiskies in Kentucky (Old Forester and Early Times) at the time,

not to mention the most successful whiskey in the world in Tennessee (Jack

Daniel's). For another, the "Old Crow" brand itself wasn't part of the package;

that brand had gone to W. A. Gaines (another Edmund Taylor associate), and from

there to National Distillers, and from there to Jim Beam. The whiskey lost a lot

in the translations, and what had once been America's premier bourbon whiskey

had degenerated to a 36-month, decidedly bottom-shelf product that Brown-Forman

would not wish to be associated with even if it were possible.

Their intention with Woodford Reserve has been to create a

unique, and superior, kind of Kentucky Bourbon for sale to a small number of

people who would appreciate it, and to produce that whiskey in a location that

was as beautiful an expression of the Kentucky bourbon heritage as its single

product.

So how did all this come to pass? It starts in 1993, or

thereabouts, when the Brown-Forman company began a very ambitious project, one

that no other distiller in the United States had ever attempted, at least not as

completely. Headed by then-master-distiller Lincoln Henderson and distiller Dave Scheurich, the project

included not only introducing and marketing a completely new brand, but also the

invention and engineering,

to

modern specifications, of a method of distilling bourbon whiskey that had been

forsaken generations ago. It also involved restoring a collapsed and derelict abandoned

farm and distilling site, not just to a condition that would allow production,

but to a pristine, world-class tourist destination in its own right.

to

modern specifications, of a method of distilling bourbon whiskey that had been

forsaken generations ago. It also involved restoring a collapsed and derelict abandoned

farm and distilling site, not just to a condition that would allow production,

but to a pristine, world-class tourist destination in its own right.

The result of the former can be enjoyed in the whiskey pictured

here.

The result of the latter is why we are visiting the Woodford Reserve Distillery

today.

When the Louisville-based company purchased this site, it was not

the first time they had owned it. The distillery, which Oscar Pepper sold in

1878 to Leopold Labrot and James Graham barely survived Prohibition, and even

though it was re-started after Repeal, they sold it to Brown-Forman around 1940.

It wasn't the distillery, however, that was so attractive; the deal also

included some 25,000 barrels of desperately-needed bourbon whiskey aging in

their warehouses.

Brown-Forman continued to operate the distillery (still under the

name Labrot & Graham) through the next two decades. They even produced some Old

Forester and Early Times here.

But it was never really profitable, and when the bourbon market

fell out by the late 1960s, they put it up for sale. In 1972 the distillery was

purchased by Freeman Hockensmith, who converted it to produce industrial

alcohol, specifically the "gasohol" that became popular as a result of the OPEC

fuel crisis. But Hockensmith had hardly got the new water facilities built

before the crisis was resolved, leaving little market for his limited

production. He closed the distillery and it lay abandoned for over twenty years.

And then, in the late 1980s, the bourbon market took off again.

Specifically, the market for very high quality bourbon, produced in limited

amounts. Distillers began marketing "single-barrel" and "small batch" products.

Buffalo Trace (Ancient Age, then) had several brands. Jim Beam had its Small

Batch collection, as did Kentucky Bourbon Distillers. United Distillers, and

Heaven Hill were offering boutique bottlings. Seagram's, whose Four Roses brand

was only a blended whiskey in the United States, was marketing half a dozen

premium straight bourbon brands (at premium prices) in Asia and Europe. Even

Wild Turkey, who only produces one kind of bourbon, came up with premium

versions and barrel-strength mixtures. Brown-Forman needed an entry in this

market. As with everything Brown-Forman does, they wanted that entry to be

something superior, and they weren't afraid to put lots of money and lots of

technical ingenuity into accomplishing that

.

They decided to start from the ground up. They would obtain

a historic property, preferably an old distillery site, and restore it to the

condition it was in when it was brand new in the 19th century. They would

install copper pot stills of the type used in Scotland and Ireland... and

nowhere in the United States anymore. Invent an entirely new method of producing

bourbon whiskey on those stills (bourbon is distilled differently from Scotch or

Irish whiskey). And release the most unique and premium straight bourbon whiskey

ever made since the dawn of the 20th century.

They searched throughout several states for a suitable location.

Despite the persistent myth about bourbon only being able to be made in

Kentucky, the truth is it can be made anywhere in the United States, and there

are many historic distillery sites that might have been appropriate. Among those

that they looked at was their old property in Woodford county, and that's the

one they chose to re-purchase. The restoration, begun in late 1994, was first-rate; Brown-Forman

spent nearly two years and over seven million dollars to refurbish and restore the old landmark, and

ended up with one of the most beautiful settings in the industry.

And that is where we are visiting

this morning. We drive from Frankfort toward Versailles along the McCracken Pike among breathtakingly beautiful horse farms,

inhabited by some of the most famous equines in the world (and also many

of the less-famous, but far more commonly observed Kentucky Thoroughbred

Racing Cows!).

This is not the first time we've visited Woodford Reserve. Our

first visit was in 1998, just a couple years after it opened. It was called the

Labrot & Graham Distillery then, although it was always better known as Woodford

Reserve due to that being the name of its only whiskey. In 2003 the name

was officially changed to Woodford Reserve Distillery. And in 2011, eight years

later, you can still see plenty of pre-2003 barrels marked Labrot & Graham aging

quietly and waiting to be bottled as Woodford Reserve. We've been here a couple

other times as well, including Chris Morris' and

Michael Veach's intensive full-day Bourbon Academy session, which they

continue to hold at various times.

Woodford Reserve's visitor tour has always been one of the most

comprehensive of any of the distilleries. Some time ago they began charging an

admission charge, which some find irritating. They have also added two even more

intensive tours (also for a fee, but for these tours the fee is appropriate).

One is called the National Landmark tour; the other is appropriately named "Corn

to Cork". They are offered only three days a week, and only once each day.

Fortunately, they are consecutive, and we are taking both tours today.

WARNING: If your interest in how bourbon is made and/or the

history of bourbon in the Glenn Creek region is only superficial, you might want

to limit yourself to the standard tour. Both of these tours are definitely

oriented toward folks who already have a little knowledge of both... and,

especially for the Landmark tour, are up to a lot of walking around.

The Corn-to-Cork tour starts at 9:30 in the morning. It's a long

tour, lasting a little over two hours, and we will be moving back and forth

throughout the distillery areas in an intricate dance so as to avoid the regular

tours, which spend much less time at each station. Our tour guide is Steve.

Apparently there are two Steves, Steve B. (think Barrel) and Steve M. (think

Mash). Steve Barrel is funny, smart, very knowledgeable, and entertaining...

just what a guide should be (and too often aren't).

A chemistry teacher before

assuming his present identity, Steve was able to keep everyone's attention even

while showing us (successfully!!) what difference the position of a single

hydrogen atom in a molecular chain makes to the resultant alcohol. Yes,

the tour does go that deeply into it.

A chemistry teacher before

assuming his present identity, Steve was able to keep everyone's attention even

while showing us (successfully!!) what difference the position of a single

hydrogen atom in a molecular chain makes to the resultant alcohol. Yes,

the tour does go that deeply into it.

The bus takes us down the hill to the distillery building, where

we are greeted by Elijah, the distillery cat. Not at all shy around strangers,

she will charm her way into getting petted by each of us before the morning is

over, sometimes taking time out to monitor the other tours going on.

As we enter the building, we gather around the display of corn,

rye, and malted barley as Steve goes over the basics of how bourbon whiskey is

made and how it differs from other types.

It's

pretty much the same demonstration given for the normal tour, and indeed for

just about any bourbon distillery's tour. He spends a little more time on it,

and answers some tough individual questions that indicate he isn't operating

just from a script. He talks about the fermenting tanks, of which there are only

four. They are made of cypress wood and were built new for the distillery. Steve

says they're likely to last over a hundred years. They are very small by normal

distillery standards, each holding "only" 7,500 gallons of mash. The distillery

produces less than 50 barrels of bourbon a day, compared to other distilleries

whose output is over twenty times that.

It's

pretty much the same demonstration given for the normal tour, and indeed for

just about any bourbon distillery's tour. He spends a little more time on it,

and answers some tough individual questions that indicate he isn't operating

just from a script. He talks about the fermenting tanks, of which there are only

four. They are made of cypress wood and were built new for the distillery. Steve

says they're likely to last over a hundred years. They are very small by normal

distillery standards, each holding "only" 7,500 gallons of mash. The distillery

produces less than 50 barrels of bourbon a day, compared to other distilleries

whose output is over twenty times that.

Sometimes much less than 50 barrels a day.

The fermenting tanks are filled with a slurry of cooked corn, rye, and malted

barley known as the mash. Yeast (Woodford Reserve uses a proprietary yeast that

must be built out from a tiny ampule to about 940 gallons) is then added to the

mash and the fermentation begins. It lasts between five and seven days, and then

the mash is considered to be ready for distillation.

And

all during this time, samples are being tested in the lab.

And

all during this time, samples are being tested in the lab.

On the regular tour, the guests are taken past

the lab room where they can see the test tubes and beakers. On this tour, Steve

takes us INTO the lab room, where we get to use mash that we obtained ourselves

from the fermenting vats and distill it in the same tiny glass still where each

batch in the "real world" is carefully tested. Here also are the sample bottles

from every batch ever made (or at least going back a long time), each neatly

labeled.

And, as our chemistry-set still begins to bubble and steam, Steve

sets up a slide on the microscope and gives each of us a chance to see yeast

cells close-up. He also shows us how a hydrometer works and what acid/alkali

testing reagents do.

These are not displays set up just for tourists; they

are the same equipment being used daily to produce this whiskey.

These are not displays set up just for tourists; they

are the same equipment being used daily to produce this whiskey.

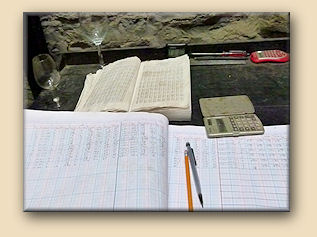

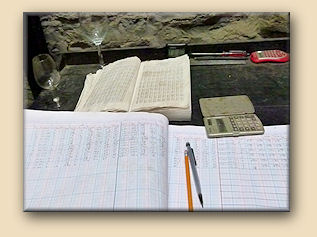

What Steve doesn't show us are the computer consoles, and

there is a good reason for that: There aren't any.

Oh, it isn't as if there might not be an Excel spreadsheet or an iPad around somewhere, but

the production of Woodford Reserve is regulated by hand. Sitting alongside the set of

whiskey safes (those are the ornate glass 'n' brass boxes where whiskey coming off each of

the stills can be accessed and tested) is a thick logbook full of handwritten

readings and notations, a reference book, and a couple of hand calculators.

The lab is the same way.

The lab is the same way.

Pencil sharpeners are important

tools around here.

Certainly one of the most distinctive and unique features of the

Woodford Reserve distillery -- actually three of them -- are the beautiful

copper pot stills, built by the Forsyth company in Rothes, Scotland. Stills of

this type are normal for producing Scotch and Irish whiskies, and once upon a

time, long ago but not so far away, that kind of still was commonly used to make

bourbon and rye whiskey in America. Not anymore. The continuous, or column,

still was perfected and adapted for use in whiskey distilleries by Aeneas Coffey

in the early 1830s, and became a big hit with American whiskeymakers. While that

kind of still is certainly well-suited for large-scale alcohol production, its

use for higher-quality (i.e., lower proof and more flavor) whiskey was (and

remains) rarely exploited, except by American distillers --  who

have perfected their techniques with it to the point that bourbon (and American

rye) can be said to draw some of its very character from the column stills.

who

have perfected their techniques with it to the point that bourbon (and American

rye) can be said to draw some of its very character from the column stills.

Well, most bourbon anyway. Not Woodford Reserve. Or at least not

the part of it that is distilled at this distillery.

And we'll get to more of

that later...

The fermented mash from the cypress tanks, once it has been

deemed fit to distill, is first pumped from the fermenter tank into Still #1,

which is known as the "beer still". Most whiskies are made using what is called

"wash"; that is, the liquid left after the solids are strained off. For some

reason, that does not work for bourbon. The nature of the whiskey demands the

use of the full mash, solids and all. The beer still makes use of the full mash,

and uses steam to vaporize the alcohol. The vapors rise up the gooseneck and

then cools as they pass through a condenser. The beer still is not designed to

be efficient; it's designed to separate the solids (which drain out the bottom)

from distillable liquid. Here they call this "low wine", and it's about 40 proof

(20% alcohol), although that term in most other bourbon distilleries represents

a product that is much higher proof than that.

It is this 40-proof low wine that is then pumped into the 'high

wine' still, where it is heated again, and again the alcohol is vaporized. This

time when it has gone through the condenser, it comes out as a 100 - 110 proof

liquid called high wine.

The high wine then goes into the third still (called the "spirit still") and is

distilled yet a third and final time, resulting in a spirit at about 158 proof.

Surprisingly, that is considerably higher that the proof bourbon is normally

distilled to, using the so-called high-proof method of the column still.

It is then diluted with water to 110 proof to be put into the

barrels. This, too, is unusual, as the normally column-still-produced bourbon,

while originally distilled to about 140 proof, is nearly always diluted only to

125 proof (the legal limit) in order to be more efficient (at the expense of

some flavor).

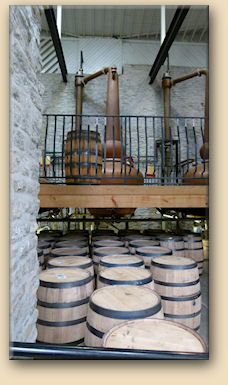

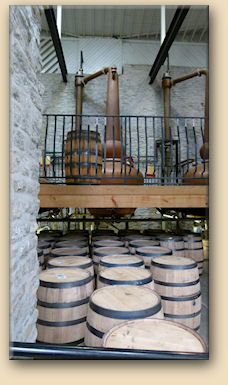

The three pot stills are lined up along the right side of the

building, and made more accessible by a lovely wooden deck built around them.

Under

the deck, in an area now being used for empty barrel storage, are foundations

for another three stills.

Under

the deck, in an area now being used for empty barrel storage, are foundations

for another three stills.

Here you see one of the foundations

being demonstrated by Elijah, the distillery cat.

The stills have a life expectancy of many years, but they will

eventually need to be overhauled. When that happens, says Steve, the three brand

new stills will be installed first so that there will be no down time at all in

production. After which, the restored stills will come back online, doubling

capacity. Steve didn't mention this (nor did we ask), but that would likely be

the time for them to introduce their long-awaited all-pot-still brand. You see,

the bourbon in a bottle of Woodford Reserve Distiller's Select is not all

whiskey that was distilled here, and the story behind that is, while perhaps a

bit embarrassing, a tribute to the quality of Brown-Forman whiskey. Remember

back when we said that the restoration was begun in 1994 and took nearly two

years? Well, the first bottles of Woodford Reserve straight bourbon whiskey were

offered for sale in 1996 which, if you think about it, is impossible. Or at

least against the law. What was actually in those bottles was bourbon that

Lincoln Henderson, Brown-Forman's master distiller, carefully selected from

existing Old Forester stock, distilled the conventional way in their column

still at the Louisville suburb of Shively. The whiskey used for that brand is

ordinarily about four years old, or maybe a little older, but the barrels

Henderson selected were 7 to 8 years old, and they were of extraordinary

quality. Distillers call these "honey barrels" and it was these specially

selected barrels that provided the whiskey in the original "Distillers Select".

The idea was to have a product that could be enjoyed while waiting for the

whiskey being made here to mature. At the time, their intention was to introduce

Distillers Select to a small region only, and it may have been to release the

fully pot-distilled product as a separate brand. Certainly, they were not

expecting what happened next, which was that Woodford Reserve Distillers Select

took off like lighting, winning all kinds of awards and medals. And press

attention. And demands for more of the product. In fact, it became a huge hit.

Problem? Well, one might not think so; but one would be wrong. There were (at

least) two big problems. The first was that the public enjoyed the flavor

profile of the existing bourbon, and when they attempted to create a mixture

containing a significant portion of the pot-distilled product they found its

distinctive flavor a bit overwhelming. In test after test they found that the

more they added, the less people accustomed to the old flavor accepted it. In

order to meet their own commitment to product integrity, the brand would have to

continue as partially (some believe mostly) the "best of" the bourbon originally

made to be Old Forester. The second problem is that, with Distillers Select

having achieved such a level of popularity, and the output of these pot stills

so small, it takes all they can produce to provide the pot-distilled portion of

the existing formula. The three copper stills and the four small fermenters at

Woodford Reserve would never be able to produce enough bourbon at this

distillery to continue Distillers Select and also provide for an all-pot-still

regular brand (although they do create special bottlings from time to time, and

those are made from only bourbon distilled here).

On the other hand, when the new stills (and presumably the

new fermenting tanks, for which there is also expansion room) are installed,

they will have that capacity. Bourbon distillers are very patient people; they

have to be. We, who enjoy the fruit of their labors, will simply have to abide.

[sigh]

They are not filling barrels this morning, but Steve shows us how

each is filled and bunged, and then rolled out to the warehouse. In the

warehouse we learn about the advantages of aging bourbon in a

temperature-controlled stone-walled environment. One tends to imagine that such

ideas as climate-control are pretty modern. Not so. We learn that within only a

couple years after their construction in 1838, the need for temperature control

had become quite apparent, because the steady temperatures of the stone-walled

warehouse slowed the aging processes dramatically. A system of steam pipes was

installed which allowed the temperature to be raised as needed.

This

allowed more than one hot-cold cycle per year and thus allowed very accurate

control of the aging process.

This

allowed more than one hot-cold cycle per year and thus allowed very accurate

control of the aging process.

By the way, those three very impressive glazed terracotta tile

warehouses that dominate the view as we enter the distillery grounds are empty

and unused. They were built in the '30s when Labrot & Graham was cranking out

whiskey as fast as it could to keep up with the booming demand for new whiskey.

It was for the 25,000 barrels of bourbon stored here that Brown-Forman bought

the distillery in the first place -- they had actually managed to sell more Old

Forester than they had product to fill and desperately needed the aged bourbon.

The warehouses continued to be used until they sold the distillery in 1972.

Since industrial alcohol isn't barrel-aged, it's doubtful that Hockensmith used

them, and the restored distillery doesn't produce enough barrels to even fill the

stone warehouses, let alone the more modern ones. We say "more modern" with a

little bit of a grin, since even those are nearly seventy years old! The

warehouse closest to the two stone buildings is used for shipping/receiving; the

other two simply lay empty.

The warehouses continued to be used until they sold the distillery in 1972.

Since industrial alcohol isn't barrel-aged, it's doubtful that Hockensmith used

them, and the restored distillery doesn't produce enough barrels to even fill the

stone warehouses, let alone the more modern ones. We say "more modern" with a

little bit of a grin, since even those are nearly seventy years old! The

warehouse closest to the two stone buildings is used for shipping/receiving; the

other two simply lay empty.

The story about the terracotta warehouses, as well as the origins

of Elijah Pepper and his family, is one we learn on the second tour, the

National Landmark Tour, given by Bill Conrad. Bill is an historian of Kentucky

whiskey history, and one of the very few people we know who can lead visitors

through the tangled web of distillery and brand ownership without losing us. We

were expecting the National Landmark Tour to be mainly concerned with the

details of how the site was restored, but Bill's presentation -- while certainly

covering that -- was centered on the history of how bourbon has always related

to life in and around Woodford county.

Among the most interesting items is the "House on the Hill", in

which Elijah Pepper's family lived. Built of logs, it was later covered

with clapboard and looked much more "modern" from the outside. Inside, it is still

logs.

Elijah

and Sarah raised eight children there, including Oscar, in a home just over 600

square feet in size. Imagine! The house is accessible, but only via an arduous

(not to mention dangerous) ascent up the hillside; Bill does not take us there,

for which we are thankful.

Elijah

and Sarah raised eight children there, including Oscar, in a home just over 600

square feet in size. Imagine! The house is accessible, but only via an arduous

(not to mention dangerous) ascent up the hillside; Bill does not take us there,

for which we are thankful.

Bill also points out the lake. The normal tour also features the

lake, the waters of which are not used for making whiskey, or even for cooling

water, but Bill's Landmark tour goes into a little more depth. He explains how

the original distillery had no lake and drew its water from the springs that can

be seen on the hill above the creek. When Freeman Hockensmith was refitting the

place to make gasohol, he built the dam and spillway that created the lake

because the high-proof process of making industrial alcohol requires a lot more

water than does making bourbon. His plans also included piping water over the

hills from the Kentucky River, but that was never completed. There was no need

for a lake full of water when the distillery was restored for bourbon

production, other than as a lovely addition to the grounds.

The

lake is open to Brown-Forman employees for fishing (there are some BIG bass in

there) and Woodford Reserve sponsors a fly-fishing school from time to time. And

of course it serves as a source of water for emergency sprinklers in case of a

fire.

The

lake is open to Brown-Forman employees for fishing (there are some BIG bass in

there) and Woodford Reserve sponsors a fly-fishing school from time to time. And

of course it serves as a source of water for emergency sprinklers in case of a

fire.

The current source of water for Woodford Reserve bourbon is their

own deep well, which for

some

reason has been left in its practical, modern, and not-at-all-romantic-looking

condition. This feature is understandably not highlighted on the normal tour,

but Bill points it out for us.

some

reason has been left in its practical, modern, and not-at-all-romantic-looking

condition. This feature is understandably not highlighted on the normal tour,

but Bill points it out for us.

By the time the bus comes to pick us up (Bill calls; there is no

scheduled "ending time" for this tour) everyone is about pooped out.

We have

walked from the foundations of original buildings that weren't restored at one

end of the site, to the roadway that crosses the dam spillway on the other.

We've looked at (but not visited) the

on-site home that Brown-Forman custom-built for distillery manager Dave Scheurich

when he began the project nearly twenty years ago, and where he and his family

have lived until he retired in December, 2010. We've seen metal herons and other sculptures by Jeff Reinhardt that seem to appear randomly

along the creek bank, and the impressive life-size distressed-steel-and-whiskey-barrel horse

sculpture by James N. Burnes just inside the main entrance gate. Woodford

Reserve, through its subsidiary

The Woodford Reserve Thoroughbred Societyô,

has creatively expanded upon the relationship between bluegrass whiskeymakers

and bluegrass race horse breeders. The program allows one to become a "virtual

owner" of a genuine Kentucky thoroughbred race horse, basically by joining its

"fan club" and following its progress through the Society's website. It began in

2006 with a lovely filly cleverly named "Distill My Heart". From a marketing and

esthetic point of view, the idea is wonderful (they now have several horses).

And had she been a big winner (she wasn't, but her daughter, "My Heartís Reserved"

has done better), the connection would have certainly been more proudly touted.

As it is, the guides at Woodford like to say, with a grin of course, that Burnes' statue is "the only horse she ever beat".

We have

walked from the foundations of original buildings that weren't restored at one

end of the site, to the roadway that crosses the dam spillway on the other.

We've looked at (but not visited) the

on-site home that Brown-Forman custom-built for distillery manager Dave Scheurich

when he began the project nearly twenty years ago, and where he and his family

have lived until he retired in December, 2010. We've seen metal herons and other sculptures by Jeff Reinhardt that seem to appear randomly

along the creek bank, and the impressive life-size distressed-steel-and-whiskey-barrel horse

sculpture by James N. Burnes just inside the main entrance gate. Woodford

Reserve, through its subsidiary

The Woodford Reserve Thoroughbred Societyô,

has creatively expanded upon the relationship between bluegrass whiskeymakers

and bluegrass race horse breeders. The program allows one to become a "virtual

owner" of a genuine Kentucky thoroughbred race horse, basically by joining its

"fan club" and following its progress through the Society's website. It began in

2006 with a lovely filly cleverly named "Distill My Heart". From a marketing and

esthetic point of view, the idea is wonderful (they now have several horses).

And had she been a big winner (she wasn't, but her daughter, "My Heartís Reserved"

has done better), the connection would have certainly been more proudly touted.

As it is, the guides at Woodford like to say, with a grin of course, that Burnes' statue is "the only horse she ever beat".

This has been a MOST comprehensive tour. In fact, if it were any more so we swear our feet would

fall off!

And Bill has been a very entertaining and enjoyable host, and

very skillful at making "old, dry, history" come alive for us on this tour.

|

Story and original photography

copyright © 2011 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

No,

Oscar Pepper's "Old Crow" whiskey was the personal choice of such as Andrew

Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, Henry Clay, William Henry Harrison, and Daniel

Webster.

No,

Oscar Pepper's "Old Crow" whiskey was the personal choice of such as Andrew

Jackson, Ulysses S. Grant, Henry Clay, William Henry Harrison, and Daniel

Webster.

to

modern specifications, of a method of distilling bourbon whiskey that had been

forsaken generations ago. It also involved restoring a collapsed and derelict abandoned

farm and distilling site, not just to a condition that would allow production,

but to a pristine, world-class tourist destination in its own right.

to

modern specifications, of a method of distilling bourbon whiskey that had been

forsaken generations ago. It also involved restoring a collapsed and derelict abandoned

farm and distilling site, not just to a condition that would allow production,

but to a pristine, world-class tourist destination in its own right.

A chemistry teacher before

assuming his present identity, Steve was able to keep everyone's attention even

while showing us (successfully!!) what difference the position of a single

hydrogen atom in a molecular chain makes to the resultant alcohol. Yes,

the tour does go that deeply into it.

A chemistry teacher before

assuming his present identity, Steve was able to keep everyone's attention even

while showing us (successfully!!) what difference the position of a single

hydrogen atom in a molecular chain makes to the resultant alcohol. Yes,

the tour does go that deeply into it.  It's

pretty much the same demonstration given for the normal tour, and indeed for

just about any bourbon distillery's tour. He spends a little more time on it,

and answers some tough individual questions that indicate he isn't operating

just from a script. He talks about the fermenting tanks, of which there are only

four. They are made of cypress wood and were built new for the distillery. Steve

says they're likely to last over a hundred years. They are very small by normal

distillery standards, each holding "only" 7,500 gallons of mash. The distillery

produces less than 50 barrels of bourbon a day, compared to other distilleries

whose output is over twenty times that.

It's

pretty much the same demonstration given for the normal tour, and indeed for

just about any bourbon distillery's tour. He spends a little more time on it,

and answers some tough individual questions that indicate he isn't operating

just from a script. He talks about the fermenting tanks, of which there are only

four. They are made of cypress wood and were built new for the distillery. Steve

says they're likely to last over a hundred years. They are very small by normal

distillery standards, each holding "only" 7,500 gallons of mash. The distillery

produces less than 50 barrels of bourbon a day, compared to other distilleries

whose output is over twenty times that.

These are not displays set up just for tourists; they

are the same equipment being used daily to produce this whiskey.

These are not displays set up just for tourists; they

are the same equipment being used daily to produce this whiskey.

The lab is the same way.

The lab is the same way.

who

have perfected their techniques with it to the point that bourbon (and American

rye) can be said to draw some of its very character from the column stills.

who

have perfected their techniques with it to the point that bourbon (and American

rye) can be said to draw some of its very character from the column stills.

Under

the deck, in an area now being used for empty barrel storage, are foundations

for another three stills.

Under

the deck, in an area now being used for empty barrel storage, are foundations

for another three stills.  This

allowed more than one hot-cold cycle per year and thus allowed very accurate

control of the aging process.

This

allowed more than one hot-cold cycle per year and thus allowed very accurate

control of the aging process.  The warehouses continued to be used until they sold the distillery in 1972.

Since industrial alcohol isn't barrel-aged, it's doubtful that Hockensmith used

them, and the restored distillery doesn't produce enough barrels to even fill the

stone warehouses, let alone the more modern ones. We say "more modern" with a

little bit of a grin, since even those are nearly seventy years old! The

warehouse closest to the two stone buildings is used for shipping/receiving; the

other two simply lay empty.

The warehouses continued to be used until they sold the distillery in 1972.

Since industrial alcohol isn't barrel-aged, it's doubtful that Hockensmith used

them, and the restored distillery doesn't produce enough barrels to even fill the

stone warehouses, let alone the more modern ones. We say "more modern" with a

little bit of a grin, since even those are nearly seventy years old! The

warehouse closest to the two stone buildings is used for shipping/receiving; the

other two simply lay empty. Elijah

and Sarah raised eight children there, including Oscar, in a home just over 600

square feet in size. Imagine! The house is accessible, but only via an arduous

(not to mention dangerous) ascent up the hillside; Bill does not take us there,

for which we are thankful.

Elijah

and Sarah raised eight children there, including Oscar, in a home just over 600

square feet in size. Imagine! The house is accessible, but only via an arduous

(not to mention dangerous) ascent up the hillside; Bill does not take us there,

for which we are thankful. The

lake is open to Brown-Forman employees for fishing (there are some BIG bass in

there) and Woodford Reserve sponsors a fly-fishing school from time to time. And

of course it serves as a source of water for emergency sprinklers in case of a

fire.

The

lake is open to Brown-Forman employees for fishing (there are some BIG bass in

there) and Woodford Reserve sponsors a fly-fishing school from time to time. And

of course it serves as a source of water for emergency sprinklers in case of a

fire.  some

reason has been left in its practical, modern, and not-at-all-romantic-looking

condition. This feature is understandably not highlighted on the normal tour,

but Bill points it out for us.

some

reason has been left in its practical, modern, and not-at-all-romantic-looking

condition. This feature is understandably not highlighted on the normal tour,

but Bill points it out for us. We have

walked from the foundations of original buildings that weren't restored at one

end of the site, to the roadway that crosses the dam spillway on the other.

We've looked at (but not visited) the

on-site home that Brown-Forman custom-built for distillery manager Dave Scheurich

when he began the project nearly twenty years ago, and where he and his family

have lived until he retired in December, 2010. We've seen metal herons and other sculptures by Jeff Reinhardt that seem to appear randomly

along the creek bank, and the impressive life-size distressed-steel-and-whiskey-barrel horse

sculpture by James N. Burnes just inside the main entrance gate. Woodford

Reserve, through its subsidiary

We have

walked from the foundations of original buildings that weren't restored at one

end of the site, to the roadway that crosses the dam spillway on the other.

We've looked at (but not visited) the

on-site home that Brown-Forman custom-built for distillery manager Dave Scheurich

when he began the project nearly twenty years ago, and where he and his family

have lived until he retired in December, 2010. We've seen metal herons and other sculptures by Jeff Reinhardt that seem to appear randomly

along the creek bank, and the impressive life-size distressed-steel-and-whiskey-barrel horse

sculpture by James N. Burnes just inside the main entrance gate. Woodford

Reserve, through its subsidiary