American Whiskey Ohio Division

Indian Creek Distillery |

|

Oh great, great, grandfather, if you could only see me now!

![]()

WE DON'T update these pages very often. When we first began writing about

American spirits and how they came to be the way they are "today" (meaning

"day-before-yesterday, when we were writing most of them), things really hadn't

changed all that much, and the few bourbon distilleries left (there were no rye

distilleries) were the same ones that had been operating since the 1930s. The

brands were nearly all brands that existed that far back, or further. And even

old, collectible bottles were of brands whose "grandchildren" could still be

found on liquor store shelves today. Old Grand Dad, J. W. Dant, Hiram Walker,

Wild Turkey, Harper, Fitzgerald, Old Weller.

There were also names that no longer existed even in most folks' memories, let

alone store shelves. A lot of these were rye whiskies, since that was America's

preferred type everywhere but in the southern states. Mostly from Pennsylvania

and Maryland, we began discovering brands such as Mount Vernon, Sam Thompson,

Large, Schenley, Braddock, and of course, Old Overholt (whose name at least can

still be found). Being more fascinated by the history of American whiskey than

by which one tastes better than another one, we sought out and paid a lot of

attention to these no-longer-existing examples.

Then came the explosion of new distillers, beginning in the early part of this

century. For awhile, it seemed as though every brand new shiny-clean distillery

had to strive to make a connection with some sort of historical past. Young

people came out of distilling school with visions of restoring the ol' tyme

glory, like their great-grandfather used 'ter drink. Happily, that concept is

being changed over to a more suitable-for-modern-times feeling of producing fine

spirit made for modern drinkers by modern distillers. A very good example of

that idea is New Riff Distillers in

Newport, Kentucky. We recently wrote an article about their distillery, which is

just now beginning to produce true Kentucky bourbon whiskey as an Urban bourbon,

very mindful of its heritage, but realized through modern methods.

At the opposite end of that spectrum lies the tiny

Indian Creek

Distillery that produces Staley rye whiskey in rural western Ohio. As

historic American whiskey goes, this may be the ultimate expression. As an

example of the connection between American distilled spirits and the heritage of

the American pioneer spirit itself it is, by far, the most comprehensive we've

ever seen. Those who have been lucky enough to visit George Washington's

restored distillery at Mount Vernon have experienced a small taste of American

whiskey's history, and a necessarily institutionalized taste at that. Believe it

or not, the real deal exists. It's in the village of New Carlisle, Ohio. And it

wasn't restored from an archeological dig; it's been here since the beginning of

the 19th century.

The Staley family arrived on the shores of what would become Harper's Point,

Virginia in the mid-1700s. Like so many of our founding stock they came here

from Holland, having fled to there a century or two before to escape political

and religious repression in their native England. Like so many other families

(see more about that HERE), they migrated to neighboring areas. One branch ended

up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. That was Joseph and Julianne Staley. They had

sixteen children. Shortly after the Revolution and the establishment of the

federal United States, three of the sons moved out to the wilderness of

Northwest Territory. Just what their motivation was is speculative, but it could

well have been the same as that of many early pioneer families who were not

particularly in agreement with overthrowing the government of their benefactors

and who were, therefore, at some real risk when the revolution left them on the

wrong side of political favor. Or, it could also have been related to the fact

that this was shortly after the Whiskey Rebellion had made it clear that the

Federal government, not the individual states, was the authority (a lesson that

would be repeated with more drastic results a bit less than fourscore and twenty

years later).

Whatever the motivation, Elias Staley and his brothers David and Henry, all

skilled millwrights, began building mills for settlers in the Indian-controlled

territories north of the Ohio River. One of Elias' clients was John Rench, who

purchased his 160-acre tract along the Indian Creek from the native Miami tribe.

Rench sold the farm to Elias in 1818. Staley married Hannah Retter who was from

Frederick, Maryland in 1826, and before he brought his bride to her new home, he

built her a brick Federal house, a fruit kiln, a sawmill, and (especially

important for our purposes), a distillery and bondhouse.

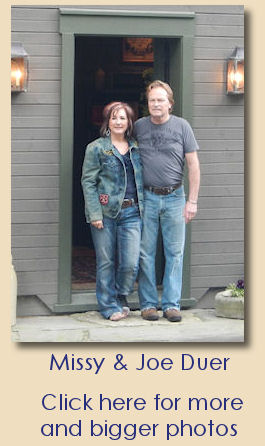

We know this, because it was told to us by Elias Staley's great, great

granddaughter, Missy Staley Duer, who represents the 6th generation to live in

this same brick Federal home. Each generation has been given the mission of

doing something important to further the development and preserve the history of

this farm. And this, friends, is what "heritage" is all about.

Different generations have done their parts in different ways. Missy's mother,

who was involved in several local historical projects, had the place made up for

touring, as the historic site that it is. She concentrated mainly on the house

and the barn, and had hoped her daughter would restore the old grist mill, which

is one of the rarest examples in Ohio, if not the whole country. She wasn't

particularly interested in the distilling equipment that had been hastily

gathered up and stuffed into a loft in the barn when Prohibition went into

effect in 1920. In fact, she probably didn't even know it was there. Missy and

her husband Joe Duer, wouldn't have known, either, except that when they went to

clean up the barn for public tours, they found the distilling equipment --

including the original two copper pot stills -- and cleaned them up to include

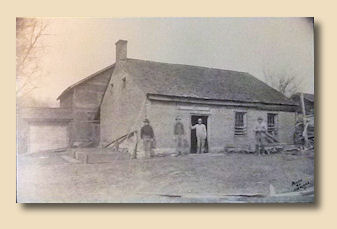

them as a display item. The old distillery building was beyond repair, but they

built a replica, using the original blueprints and placed the distilling

equipment there.

Oh, did I say "original blueprints"? Indeed I did. The Staley family are not

"hoarders" in the sense popularized by modern reality shows, but they did save

things like documents. All of their documents. Just about every piece of paper

ever owned by the Staleys still exists, carefully stored away. The original

blueprints for the distillery are all at hand. So are the original recipes,

production methods, invoices, receipts for materials, timetables... everything.

Some are on display in their visitor center; much, much more is kept in drawers

in the house's library.

Joe Duer is just the sort of man who SHOULD be married into the Staley family. A

modern renaissance man, there's not much he hasn't had some experience doing,

and probably nothing that he couldn't do if he had a mind to. In the process of

helping his wife establish her own mark on the family home, it occurred to Joe

that those stills might actually be useable, if one knew how to use them. And

all the knowledge accumulated by a family that had been distilling eastern

Pennsylvania-style rye whiskey for generations was available to him, as well as

modern training. Joe Duer set out to learn how to be a 19th century whiskey

distiller.

First of all, since he already had the pair of 19th century stills, he needed

them made useable again. He contracted a local coppersmith, who informed him

that the stills were in excellent shape and needed only some cleaning. The

coppersmith has since built or repaired several other pieces of equipment, but

the stills themselves are pretty much what they were in 1920... which is pretty

much what they were in 1820.

Next, he contracted with a crew of old-line Amish builders to re-create the

still house itself. No, it isn't put together with pegs and square nails, but it

is built the way the Amish build today, and that's pretty much the way they

always have.

Next, although not necessarily in this order, Joe learned to be a 19th century

distiller of rye whiskey. That's a LOT different from distilling modern

bourbon-like rye whiskey. There's a lot you need to learn, and a lot you need to

NOT learn. And what you need to MAINLY learn is how 19th century distillers

really worked. Some of those techniques are quite different from what's done

today. For example, federal law requires anything that will be called "whiskey"

to be stored in oak containers. Elias Staley's whiskey was never stored in oak

containers. Elias used barrels made from hickory. The requirement for using oak

began with the Bottled-in-Bond act of 1897 and wasn't universal until the end of

1933. Whiskey aged in hickory barrels doesn't taste like whiskey aged in oak

barrels. If you don't believe that, just get into a discussion with bourbon

enthusiasts debating the nuances of oak barrels made from first-growth oak or

new-growth, or from the top or bottom of the oak tree. Yes, there really are

some folks that into it. Hickory? Fageddabouddit! But that's what Elias Staley

whiskey (and probably many others' as well) was aged in. So's the current aged

whiskey. "How's that?" you say. Well, true to the law of the land, Joe makes

sure that every drop of his rye whiskey is stored in oak barrels. But the oak

barrels also contain toasted slats to add flavor. That's not so new. Several

artisinal distillers do the same, and that's the distinguishing factor in what

makes Maker's Mark 46 special. What's different is that Joe's toasted slats are

hickory. Problem solved!

And then there are the hops.

Hops? Uh, isn't that something you find in beer?

Uh, well, yes it is. In fact, it's hard to imagine beer made without hops. Hops

are the buds of a plant that provide an antibiotic effect on fermenting grain,

such that the yeast works just fine while the bacteria that you don't want dies

off. Modern distillers use other methods of accomplishing that, not hops. But

Elias Staley (and other 19th century distillers) used hops. Not a lot. Not

enough to make the whiskey taste like distilled beer. But enough to contribute

something to the flavor that is missing in rye whiskey made today.

Elias Staley rye is not "pure" rye whiskey. It never was. Although he won't tell

you the exact proportions, Joe Duer makes his rye whiskey from rye, corn, and

malted barley. A glance through the old distiller's books tells us that such a

recipe was typical for the style of rye whiskey made in Maryland and in eastern

Pennsylvania (such as Lancaster). Decreasing the rye and increasing the corn

pretty much gives you the formula for the type of whiskey made in Virginia,

including what was once the western half of Virginia and now known as the

Commonwealth of Kentucky.

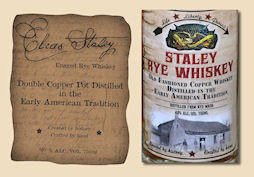

You won't find an example of the original Staley rye whiskey, no matter how hard

you look. If someone offers to sell you one, run away, fast. Bottled whiskey has

been around for a very long time (although not as long as Staley rye), but the

early bottles were hand-blown and it's very rare to find one today.

Mass-produced bottles came in around the turn of the 20th century, and many

distilleries began to bottle and label their products at that time. Staley did

not. Like many small, locally sold whiskies, Staley was sold in barrels to

retailers who would dispense either single drinks or containers; or you could

bring your own jugs to the distiller to fill them there. That's not possible

today, and Missy and Joe had the (kind of delightful) challenge of designing

bottles and labels for both their authentic unaged rye whiskey and their

(equally authentic, maybe even more so) aged product. The packaging is quite

different for the two expressions. The white whiskey is bottled in a plain,

turn-of-the-last-century style bottle with a really good example of the sort of

hand-written label one might expect from an 1800s product. The aged whiskey, on

the other hand, comes in a lovely sculptured bottle reminiscent of cut-glass,

the sort one might find on the back bar display in a New Orleans saloon.

Elias Staley rye whiskey, both unaged and aged, has won awards, but that seems

to be somewhat less important to Joe and Missy than it might be for many another

new distiller out there. The Staley's are not looking to become bankrupt any

more than anyone else, but the profitability of Elias Staley whiskey isn't

really a major factor in their financial life. The integrity and historical

accuracy of that whiskey, on the other hand, is of paramount importance, in ways

that we've never seen with other new (or old) distillers.

Missy

Staley Duer's mission in life has been to do something to bring honor and

recognition to the family heritage, and she and her husband have achieved that

in a way that would make any grandparent proud.

Missy

Staley Duer's mission in life has been to do something to bring honor and

recognition to the family heritage, and she and her husband have achieved that

in a way that would make any grandparent proud.

We've visited the Indian Creek Distillery several times, including in 2012 when they were hosting a reenactment of a military camp in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812. It was a great afternoon, and we had the unique opportunity to share a couple of drinks of period-accurate rye whiskey the President of the United States.

No foolin'.

Click here to see some photos of that

day.

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2014 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|