American Whiskey The Kentucky Bourbon Academy at the Filson Historical Society |

|

SO YOU THINK you know a few things about Kentucky

bourbon?

Well, you probably do. So do we.

But there's always something new to be learned; in fact, there are often a

LOT of things about the history of American spirits to discover,

and each carries the potential to re-shape whole segments of what we

THOUGHT we already knew.

Most of us enjoy an occasional enhancement to our knowledge-base from time

to time, but one person we know who actually does this for a living is our

good friend Michael Veach of Louisville, Kentucky. Mike is nominally a

special-collections archivist for the prestigious Filson Historical

Society.

Unofficially, he is recognized -- by the Filson Society and by

virtually every documenter of Kentucky whiskey history -- as the highest

authority there is on the subject of Kentucky bourbon. In 2006, he was inducted

into the Bourbon Hall of Fame, an honor usually bestowed only upon the

most highly-respected and influential contributors within the industry.

Those few writers and intellectuals who are included will all readily

acknowledge how much their own contributions resulted from what they

learned from Mike Veach. In fact, we do believe that there is very little

that has been written about the history of Kentucky bourbon that was not

learned either directly from Mike or from someone else who learned it from

him. And that certainly

includes much of what you will read on our own pages.

Unofficially, he is recognized -- by the Filson Society and by

virtually every documenter of Kentucky whiskey history -- as the highest

authority there is on the subject of Kentucky bourbon. In 2006, he was inducted

into the Bourbon Hall of Fame, an honor usually bestowed only upon the

most highly-respected and influential contributors within the industry.

Those few writers and intellectuals who are included will all readily

acknowledge how much their own contributions resulted from what they

learned from Mike Veach. In fact, we do believe that there is very little

that has been written about the history of Kentucky bourbon that was not

learned either directly from Mike or from someone else who learned it from

him. And that certainly

includes much of what you will read on our own pages.

So, how does an ordinary mortal obtain the blessing of being able to

gather at the feet of this great teacher?

Well, first of all, there is probably no more

approachable person on the planet than Mike. Anyone can ask him anything

about bourbon whiskey and the Kentucky distilling industry and he'll

happily tell you everything you want to know -- and then some.

But if you're REALLY serious about learning the story of this fascinating

aspect of American spirits, you can attend what he calls the Bourbon

Academy. This is a full-day lecture/seminar/sampling/discussion session

that Mike presents twice a year at the

Filson Historical Society's lovely

headquarters in the Ferguson Mansion on 3rd street in downtown Louisville.

How serious do you need to be?

Well, it ain't free. Like any legitimate

learning experience, there is a fee. But you definitely get what you pay

for, and what you learn is documentable and transferable. In fact, if you

are a professional bartender or waiter with a Kentucky S.T.A.R. (Server

Training in Alcohol Regulations) certification, or it's equivalent program

in any other state, your employer can save a big chunk of liability

insurance costs, way more than the tuition, by sending you to one of these sessions.

Many of those attending today are here for exactly that reason.

And if, like ourselves, your main contribution to the

spirits industry is that of faithfully consuming the products of their

labor, and you would like to learn more

about what Kentucky bourbon is, was and may be becoming, directly from one

of the legends of the realm -- and if you can devote a very full and

comprehensive day -- it would be well worth the

price of a couple bottles of good bourbon to enroll in one of these

courses.

Oh yeah, you have to go to Louisville to do it. But that

just might be the best part of the whole experience. Let us explain...

The Bourbon Academy itself runs from 9:00 in the morning until 5:00 in the

afternoon. That's a full day, and it includes a box lunch served onsite.

Okay, that's the "official" part. But Mike Veach is not the sort of

"celebrity speaker" who separates himself from his "students". Louisville

is the center -- both historically and in current practice -- of the

Kentucky bourbon industry. It is also a vibrant and very urbane city,

especially with regard to dining and imbibing. Students who wish to extend

their time with Mr. Veach (he's a historian, not a professor, although we

do have a tendency to call him "Doctor" occasionally) will find him more

than willing to show you some of his own favorite haunts. The Kentucky

Distillers Association, one of the Academy's sponsors, has long offered a

touring guide to many of the state's bourbon distilleries, using a

"passport" system to encourage visiting all of them. They call it the

Kentucky Bourbon Trail. On a

more local level, the Louisville Convention & Visitors Bureau, another

Academy sponsor, has a similar (if somewhat more comprehensive)

self-guided tour of the finest bourbon bars and restaurants in and around

the city of Louisville. They call theirs the "Urban

Bourbon Trail" and it provides a "tour" of the best bourbon bars in

Louisville. All fourteen of them... (as of March, 2012; more are added

from time to time). Their "passport" booklet is included with the

souvenirs at the Academy (or you can get one at any of the Urban Bourbon

Trail bars) and each bar has its own stamp to show that you've visited it.

Collect six stamps and you can get a certificate and a free T-shirt. We

strongly recommend that you use taxis or public transportation if you

intend to do this in one visit. Or walking, since it's easy to find six of

these in an area within walking distance from one another. Most are also

restaurants, and all of those are first-class. After the Bourbon Academy

session, several of us -- along with Mike -- walk a couple of blocks to

Buck's Restaurant and Bar, a lovely establishment and one of the stops on

the Urban Bourbon Trail.

There are occasionally other chances to attend these sessions as well. The Bourbon Academy has been presented from time to time in other locations; for example, the day we attended there were members who are now looking to bring a session to Chicago later this year.

So, what do we learn today? Remember that we've already

attended a few Filson bourbon presentations (see the

menu for a couple of them) and several of Mike's other personal

appearances, so what's left to learn? Well, plenty. First of all, Mike

learns continually; so what he passes on to his students changes and

increases nearly every time we see him. Secondly, the other members of the

class often consist of distillers, liquor merchants, mixologists, and

others with their own industry knowledge, and we all learn from each

other's comments and questions. Mike's presentation is a sort of

combination lecture and seminar; if no one would ask any questions or

make any comments (a somewhat unthinkable situation, by the way) he could

easily make a straight lecture of the event. But one of Mike's strengths

as a teacher is that he continually adjusts his pace in response to the

feedback he gets from his audience. He solicits questions and comments,

and adjusts his content to fit. By expertly manipulating his presentation

to his audience's interest level, he makes a "lecture" seem much more like

a "conversation". Along the way, he also allows the expertise of his

audience members to add to the experiences of their peers. When the day is

done, one feels as though s/he has been the recipient of knowledge from

not just one, but several, educators.

So, what do we learn today? Remember that we've already

attended a few Filson bourbon presentations (see the

menu for a couple of them) and several of Mike's other personal

appearances, so what's left to learn? Well, plenty. First of all, Mike

learns continually; so what he passes on to his students changes and

increases nearly every time we see him. Secondly, the other members of the

class often consist of distillers, liquor merchants, mixologists, and

others with their own industry knowledge, and we all learn from each

other's comments and questions. Mike's presentation is a sort of

combination lecture and seminar; if no one would ask any questions or

make any comments (a somewhat unthinkable situation, by the way) he could

easily make a straight lecture of the event. But one of Mike's strengths

as a teacher is that he continually adjusts his pace in response to the

feedback he gets from his audience. He solicits questions and comments,

and adjusts his content to fit. By expertly manipulating his presentation

to his audience's interest level, he makes a "lecture" seem much more like

a "conversation". Along the way, he also allows the expertise of his

audience members to add to the experiences of their peers. When the day is

done, one feels as though s/he has been the recipient of knowledge from

not just one, but several, educators.

Oh, did I forget to say anything about actually TASTING any of this

bourbon we're all here to learn about?

You betcha!

As each section of the presentation is brought forth, we are treated to a taste of one of several (six in this one-day course) very different Kentucky whiskies. We will explore how each of them represents a type of bourbon (or rye, in one case, and Tennessee whisky in another) and how they differ from one another.

We begin with Old Forester 100-proof "Signature" bourbon. Mike shows us

how to "nose" the whiskey, and what elements to look for. Then how to

properly "taste" the whiskey. Old Forester is, perhaps, the most "classic"

Kentucky bourbon -- at least of the Louisville "style" -- still available,

and a perfect

We begin with Old Forester 100-proof "Signature" bourbon. Mike shows us

how to "nose" the whiskey, and what elements to look for. Then how to

properly "taste" the whiskey. Old Forester is, perhaps, the most "classic"

Kentucky bourbon -- at least of the Louisville "style" -- still available,

and a perfect

starting point to introduce people to what bourbon is all about.

Like all bourbon whiskey, Old Forester is made from more than 50% corn,

some malted barley, and an amount of rye that significantly affects the

flavor.

The next style we taste also contains some malted barley and over

50% corn, which is a requirement for whiskey that can be called bourbon;

but the third grain, which -- again -- affects the flavor, is wheat

instead of rye. What we are given to taste is Old Fitzgerald 1849, an

excellent example of the type, and another bourbon whiskey that is full of

historical importance for both Kentucky bourbon in general and Louisville

bourbon in particular. Click on the label at the right for more

information about the history of this brand (you can do the same with the

Old Forester label, too, as well as all of the others). Although both the distilleries and the companies

that owned the distilleries have changed hands multiple times over the

years, there has never been a time when Old Fitzgerald was distilled

anywhere but Louisville (well, except for the original John Fitzgerald

distillery; but there is some doubt as to whether that has any connection

other than the name. See our page on Stitzel-Weller for more on that

legend).

The next style we taste also contains some malted barley and over

50% corn, which is a requirement for whiskey that can be called bourbon;

but the third grain, which -- again -- affects the flavor, is wheat

instead of rye. What we are given to taste is Old Fitzgerald 1849, an

excellent example of the type, and another bourbon whiskey that is full of

historical importance for both Kentucky bourbon in general and Louisville

bourbon in particular. Click on the label at the right for more

information about the history of this brand (you can do the same with the

Old Forester label, too, as well as all of the others). Although both the distilleries and the companies

that owned the distilleries have changed hands multiple times over the

years, there has never been a time when Old Fitzgerald was distilled

anywhere but Louisville (well, except for the original John Fitzgerald

distillery; but there is some doubt as to whether that has any connection

other than the name. See our page on Stitzel-Weller for more on that

legend).

While we are tasting, Mike introduces us to the six elements that make up

what whiskey "tastes" like:

1. The Grain from which it is made

2. The Water used in all stages of production

3. The Fermentation procedures used

4. The Distillation procedures used

5. The Maturation process (often wrongfully called "aging")

6. The Bottling process -- selection, bottling proof, filtering, etc.

Each of these factors presents a wide range of choices, and producers of whiskey have approached all of them, separately and in combination, differently for each expression they've offered. Mike examines in detail how each of the whiskies we're tasting today deals with each of those elements, and also how today's methods differ from those popular in the past.

At the same time, we are hearing a running chronology of just how the history of American whiskey relates to the history of America itself, a subject dear to our particular hearts. Beginning with the role of distilled spirits in the early colonies (and indeed in Europe even before that), and continuing through every historical period practically up to yesterday afternoon, Mike weaves a fascinating story of how this product -- and this nation -- developed together. Sometimes despite each other.

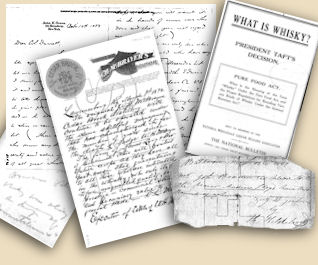

Mike's style of presentation deserves a mention here,

because it is an important part of the Bourbon Academy experience. This is

not a particularly high-tech class. Mike's audio/video system consists of

Mike, who is a big guy whose voice can fill a small room such as this

without any assistance, while appearing to be speaking at normal conversational

volume. His version of an LCD flat-screen PowerPoint presentation is a

flip-chart on an easel and a felt-tip marker. A black marker, mind you; no color-coding. The

morning begins with the passing out of study materials which illustrate

what he will be showing us throughout the day. They are Xeroxed copies of

handwritten documents dating from as far back as the 1790s. There are no videos.

There is no background music.  What

there is, is the very intimate feeling that you are sitting in Mike's

living room while he talks with you. In fact, Mike has spent many hours in

our own living room, and that's exactly the way he talks. There is a true

sense of honor in Mike's presence, and none of that "I'm unworthy" feeling

you might expect to feel if you've never met him.

What

there is, is the very intimate feeling that you are sitting in Mike's

living room while he talks with you. In fact, Mike has spent many hours in

our own living room, and that's exactly the way he talks. There is a true

sense of honor in Mike's presence, and none of that "I'm unworthy" feeling

you might expect to feel if you've never met him.

So, does "bourbon" have to be made in Kentucky? No, not at all. It has to be

made in the United States, according to a resolution (observed only in the

United States, by the way, and among nations that have agreed to it) passed in 1964,

but certainly not only in Kentucky. In fact, there are members of our

class who are distilling (and marketing) bourbon whiskey in other states.

Bourbon is a "type" of whiskey. Bourbon can be made anywhere in the United

States, including in neighboring Tennessee. But there is a quality that is

associated with "Tennessee Whiskey" that differentiates it from bourbon.

It is what is known as the "Lincoln Process" (because it is associated

with Lincoln County, Tennessee, where the Jack Daniel's distillery was

once located -- the county has since been re-drawn and the distillery is

no longer within its boundaries). The process involves filtering the

newly-distilled spirit through maple charcoal before putting it into the

barrel to age, and in 1943 the federal tax authorities declared that the

additional flavoring derived from the maple charcoal was sufficient to

invalidate the use of the word "bourbon". The entire Tennessee whiskey

industry, which at that time consisted only of one distillery, Jack Daniel's in Lynchburg, immediately declared that the U.S. Government had

designated them a special kind of whiskey, which they (Jack Daniel's, that

is, NOT the U.S. Government) have ever since called "Tennessee Whiskey".

There is no actual legal category of "Tennessee Whiskey" -- and most

people around the world do not consider Jack Daniel's as anything but

"bourbon". But in the United States it is considered (and

proudly so) a separate kind of

spirit.

Well, not completely separate. Today we learn from Mike -- many of us for

the first time -- the very entertaining story of how the giant Schenley

Company had passed on a chance to purchase the Jack Daniel's brand from

its owners, the Motlow family, in 1932. Schenley pooh-poohed the offer as

a waste of time and money, only to find themselves snubbed when the company was

later sold to

Brown-Forman (of Louisville) at a lower bid, as an expression of the

Motlow family's feelings toward Schenley.

That

was in the 1950s, about the time the "Rat Pack" and other Hollywood and

rock 'n roll stars fell in love with Jack Daniel's and it suddenly became

very popular.

That

was in the 1950s, about the time the "Rat Pack" and other Hollywood and

rock 'n roll stars fell in love with Jack Daniel's and it suddenly became

very popular.

The result of the rejection

was that Schenley vowed to build a brand new Tennessee distillery from scratch

and put Jack Daniel's out of business. Schenley already owned the Cascade

brand, which had once been a Tennessee whiskey distributed by a Nashville

merchant named George Dickel before Prohibition. They rebuilt the Cascade

distillery and established the George Dickel brand in the late '50s. As we

all know, it did not overthrow Jack Daniel's (although Mike points out

that, had Schenley's president, Lewis Rosenstiel survived long enough, it very well might

have), but it certainly remains a force in the Tennessee whiskey world

today (it is owned by world-class spirits giant Diageo) and makes a great

example of how differently whiskies that are classified as the same can be

in reality.

The limitations of a one-day class preclude doing a

comparative tasting (and it would have been appropriate, since both of

these "Tennessee" whiskies were once owned by Kentucky-based

companies), but we are

given George Dickel as an example, which is a great choice given that

nearly everyone is already familiar with Jack Daniel's.

The limitations of a one-day class preclude doing a

comparative tasting (and it would have been appropriate, since both of

these "Tennessee" whiskies were once owned by Kentucky-based

companies), but we are

given George Dickel as an example, which is a great choice given that

nearly everyone is already familiar with Jack Daniel's.

The next whiskey we taste is not bourbon. It is Wild Turkey 101-proof Rye.

Rye whiskey pre-dates bourbon as America's whiskey of choice and, although rye whiskey has

long been made in Kentucky, historically it is mostly associated with

Pennsylvania and Maryland. You can read much about rye whiskey and

American history in our pages on that subject (check out the menu), but

Kentucky Rye Whiskey did have some importance. And since the collapse of

the Pennsylvania/Maryland rye industry in the mid-1970s, the importance

of Kentucky rye has become very great indeed. The Austin Nichols company, who once

produced the Wild Turkey brand of American whiskey (and whose name still

appears on the label), had a rye whiskey in

their catalog; it was made in Pennsylvania and they never specified just

where. Later, they used rye whiskey made in Kentucky, perhaps at Glenmore

in Owensboro, or maybe at the Boulevard

distillery in Tyrone where their bourbon was (and still is) made. That's

where Wild Turkey Rye Whiskey is made today (well, there's more to the

story than that, but you might need to attend one of the Bourbon Academy

classes to uncover those tidbits). "Rye" whiskey is made similarly to

"bourbon" whiskey -- at least since the United States Code of Federal

Regulations definitions after 1933 -- except that, instead of there being

51% or more of corn, rye whiskey requires 51% or more of rye. The old

Pennsylvania and Maryland rye whiskies, those labeled "Pure Rye" contained

significantly more rye -- often 90% or more -- while the Kentucky variety

often contains exactly 51% or barely a little more.

Wild Turkey Rye is

typical of Kentucky-style rye whiskey and, even though the rye content

itself is

not overwhelming, the actual FLAVOR of the rye grain is very predominant.

Wild Turkey Rye is

typical of Kentucky-style rye whiskey and, even though the rye content

itself is

not overwhelming, the actual FLAVOR of the rye grain is very predominant.

At this point, Mike begins to speak about how the marketing of Kentucky

bourbon changed dramatically in the mid-to late twentieth century, and the

influence of the Scotch marketers with their "single malt" whiskies. He

introduces us to the concepts devised by Elmer T. Lee (and Japanese

marketers) that brought forth the "Single-Barrel" and subsequently the

"Small-Batch" and "Heritage Collection" expressions of Kentucky bourbon.

The whiskey we are tasting during this segment is Four Roses Single Barrel

and, while the "lesson" is geared toward explaining the "single barrel"

concept, Mike's choice gives him the opportunity to highlight a distillery

that produces possibly the most diverse selection of bourbon types

imaginable. Using five different yeast varieties and two different mashbills (grain recipes), Four Roses produces ten completely different

bourbons, most of which they combine to produce the excellent finished

products from that distillery. But they also bottle each of those types as

single-barrel expressions; the result is a VERY comprehensive catalog of

whiskies. We get to try just one today, and that's a great way to whet our

appetitites for more!

The final whiskey that we taste (well, not really, but the final bourbon we

taste that we know what we're tasting) is an example of what's coming up new on the horizon.

There are more and more new (smaller, artisan) distilleries coming on line

all the time, and among these, recognized as members of the Kentucky

Distillers Association, are M.B. Roland in St. Elmo, and

Alltech, in

Lexington. Alltech's brand is Town Branch, and that is the "new

kid on the block" that we get to taste today. New bourbon distillers are

(usually) not trying to compete directly with the "old boys", but offer

something different as their competitive edge. The world of bourbon

enthusiasts includes a large portion of people who are oriented toward

preservation of existing values. As "historians at heart" we tend to

sympathize with that viewpoint. But, as "historians of the future", we

can't help but be impressed by -- and support, even at the risk of our

credibility sometimes -- distillers who seek out new processes, new

methods, and even completely new products. There is a wide spectrum of

diversity here; truthfully, some of our friends make -- frankly -- really

awful spirits. Other, make some of the best spirits we've ever tasted...

but can't sell them because they don't fit into any currently-existing

legal definitions. Others are more traditional. Town Branch is a

pretty traditional-tasting bourbon whiskey. The company that makes it, Alltech, is

primarily an animal-food producer. They make high-tech nutritional

products for the dairy, poultry, and especially the Kentucky race-horse

industries. Why is that so significant?

Well, as far back as the beverage-alcohol distilling industry has existed,

it has been intimately connected with the animal-food industry. The

remnants of the distilling process is extremely high-quality grain residue

that makes for premium cattle- and pig-feed. In fact, the cattle- and

hog-feeding industries are so inter-related with the distilling industries

that neither can economically exist if denied access to the other.

However, the traditional situation is that the animal-feed company(s) are

subservient to the distillers. In the case of Alltech, it's the other way

around. Alltech is a premier animal food provider. But, instead of seeking

out distilleries to provide concentrated-nutrient grain residue for animal

food, Alltech has built a facility to provide such a product themselves.

Of course, there is a by-product... beverage-quality alcohol, such as

bourbon whiskey. So, in their case, they have a total reversal of the

historical situation. Who would have ever come up with such a thing? Well,

people who make animal food and who also love good whiskey, that's who.

The president and founder of Alltech, Pearse Lyons, just happens to be a

fine Irishman who loves whiskey and saw a chance to make some of his own.

We visited the distillery two years ago and had a chance to sample some of

what would become Town Branch. It was still aging at the time, but

it is available now. Alltech are members of the Kentucky Distillers Association now, and

so we get to

enjoy a sample of their "human feed".

Ummm... yummy!

These are not the only samples of whiskey we get to taste. As with any

good classroom experience, there is a

test at the end. This one involves a Kentucky

whiskey totally unknown to us -- well, at least  not one of those we've tasted

today -- and we are supposed

to describe it on a form with several categories requiring our evaluation.

We won't divulge the identity, in case Mike chooses to use the same

example in a future presentation, but we will say that one person

among the class did identify the whiskey, its age, and and its proof.

not one of those we've tasted

today -- and we are supposed

to describe it on a form with several categories requiring our evaluation.

We won't divulge the identity, in case Mike chooses to use the same

example in a future presentation, but we will say that one person

among the class did identify the whiskey, its age, and and its proof.

And of course there were plenty of neat promotional souvenirs provided by the sponsors.

Even a bourbon-flavored SPF 15 lip moisturizer.

"But officer, it's not what you think... it's just my

flavored lip balm, HONEST!"

Here's a great photo (John didn't take this one) of Mike Veach with

teacher's pets Lucy and Krista from BYOB (Barrel Your Own Bourbon), makers

of the popular Risky?Whisky home aging kits. Linda notes that she's

amazed at how many of the students were women, and that virtually all of

them are personally involved with bourbon, not just accompanying men who are. We well

remember just a few years ago when Linda would have been the only female

in the room, and certainly the only one who would understand what things

like "Number 4 Char" or "Bonded Distillery" meant.

Here's a great photo (John didn't take this one) of Mike Veach with

teacher's pets Lucy and Krista from BYOB (Barrel Your Own Bourbon), makers

of the popular Risky?Whisky home aging kits. Linda notes that she's

amazed at how many of the students were women, and that virtually all of

them are personally involved with bourbon, not just accompanying men who are. We well

remember just a few years ago when Linda would have been the only female

in the room, and certainly the only one who would understand what things

like "Number 4 Char" or "Bonded Distillery" meant.

The best way to get involved in the next Filson Bourbon Academy class, or

just to contact Mike for more information on those or other events where

he may be seen, he is best reached at the

Filson Historical Society.

Their page includes a website search feature -- doing a search on VEACH

will return a wealth of information about Kentucky bourbon and the whiskey

industry.

![]()

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2012 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|