American Whiskey The 9th Annual American Distilling Institute Conference |

|

Whiskey & Rum

SUNDAY, April 1st

There are some people who can take off and go anywhere they want, any time they want. No one cares.

Linda is not one of those people. People depend on her. Her boss expects her to work on Mondays, Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays.

More importantly, the people she serves need her to be there for them. It's nice to be needed. It also means you can't go to four-day conventions, at least not very often. This is one of those times when Linda doesn't get to join in.

I leave home this afternoon at around 2:30pm, arriving at the famous Seelbach Hotel in Louisville where I check in, set up my computer, and make a few phone calls. I then drive to the Brown Hotel with the bottles of whiskey that I’d committed to this experience, arriving there around 5:30.

American Distillers Institute president Bill Owens’ VIP

party and reception is already going on, with Bill somehow enjoying the time of

his life while running around trying to organize probably the most un-organizable

group of folks imaginable.

Bill is an amazing human being -- a visionary, an

artist, a "crazy" man who has absolutely zero fear (or even recognition) of

failure, and an intense desire to create once-a-lifetime experiences on the

basis of the slightest interesting suggestion.

Bill is an amazing human being -- a visionary, an

artist, a "crazy" man who has absolutely zero fear (or even recognition) of

failure, and an intense desire to create once-a-lifetime experiences on the

basis of the slightest interesting suggestion.

Often.

Sometimes I think all that stands between Bill and the proverbial lunatic asylum are Penn Jensen (ADI vice president, and nearly as much of a visionary as Bill), Leah Hutchinson (who actually coordinates -- if that's the appropriate word -- the conferences), and his personal assistants and reciprocal mentors, Nancy Fraley and Amber Hasselbring. It is certainly an honor to be invited here as a friend of Bill (no, not THAT sort of "friend of Bill.")

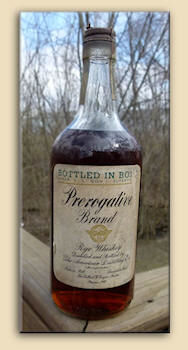

I give Bill the bottle of

Prerogative Rye that I’d brought to be auctioned off, after which he went off

and hid it somewhere. I would like to believe that he hid it so well that he

couldn't find it later and that eventually it will turn up in his luggage

somewhere, because after I went downstairs to the Bluegrass Room to

actually register and get my name badge and all that, I returned to

Bill’s party to learn that someone had apparently stolen the bottle.

Earlier, Bill’s computer and camera had also vanished; it was a pretty

disheartening way for him to begin a conference. Hopefully they will all turn

out to have been merely misplaced.

The bottle did, indeed, have some value, but I'm not about to aid a potential

thief by indicating how much. Prerogative Rye was not a premium whiskey,

and examples rarely show up on internet auction sites. I would not expect it to

bring much in a non-benefit auction. Still, I felt pretty bummed out about it,

too.

I give Bill the bottle of

Prerogative Rye that I’d brought to be auctioned off, after which he went off

and hid it somewhere. I would like to believe that he hid it so well that he

couldn't find it later and that eventually it will turn up in his luggage

somewhere, because after I went downstairs to the Bluegrass Room to

actually register and get my name badge and all that, I returned to

Bill’s party to learn that someone had apparently stolen the bottle.

Earlier, Bill’s computer and camera had also vanished; it was a pretty

disheartening way for him to begin a conference. Hopefully they will all turn

out to have been merely misplaced.

The bottle did, indeed, have some value, but I'm not about to aid a potential

thief by indicating how much. Prerogative Rye was not a premium whiskey,

and examples rarely show up on internet auction sites. I would not expect it to

bring much in a non-benefit auction. Still, I felt pretty bummed out about it,

too.

For most of the evening I toyed with the idea that this

was an April Fool's trick and that the bottle would turn up safe and sound at

the auction. Unfortunately, that did not turn out to be the case.

I stayed at Bill's party for awhile longer, then went downstairs to the

Brown Hotel's Lobby Bar, where I was delighted to learn that food was, indeed, being served,

including Hot Brown. "Hot Brown" is an iconic meal in Kentucky, consisting of

a turkey (and sometimes ham as well) sandwich, served open-faced on toast

points with tomato, bacon, and Mornay sauce. It can be found nearly everywhere

in Kentucky, but it was invented in this very hotel back in the 1920s.

In fact, the sandwich isn't "brown" at all; it's named after the hotel. Like

so many popular recipes, it was the result of desperation.

It

seems that the hotel drew huge crowds in the evening for their dinner dances.

In the early morning hours, after the dinner dance, many guests drifted over

to the hotel’s restaurant to eat. Since this was the twenties – that is,

during Prohibition – we can (or at least should) assume that there was

no alcohol involved, but dancing can certainly work up an appetite and chef

Fred Schmidt, looking for a way to get rid of excess turkey, came up

with a sandwich which became an instant hit. Not only was it added to the

regular menu, it has been copied and served just about everywhere in Kentucky...

and nearly no place else. Needless to say, a meal with such a history is very

attractive to hungry patrons who are of the distilling persuasion.

It

seems that the hotel drew huge crowds in the evening for their dinner dances.

In the early morning hours, after the dinner dance, many guests drifted over

to the hotel’s restaurant to eat. Since this was the twenties – that is,

during Prohibition – we can (or at least should) assume that there was

no alcohol involved, but dancing can certainly work up an appetite and chef

Fred Schmidt, looking for a way to get rid of excess turkey, came up

with a sandwich which became an instant hit. Not only was it added to the

regular menu, it has been copied and served just about everywhere in Kentucky...

and nearly no place else. Needless to say, a meal with such a history is very

attractive to hungry patrons who are of the distilling persuasion.

The tables in the lobby bar are, not surprisingly, located in the actual hotel lobby itself, and I take a single table. But immediately I begin looking for folks who might join me. I didn't have to wait for long. Joe & Missy Duer, who operate the Staley Mills Distillery in New Carlisle, Ohio, show up and we join and move to a larger table. Not long after that all of us meet a Canadian couple, whose distillery (Sixty-Six Gilead) is located in Ontario, very close to where Joshua Booth once occupied Lot #40 in the Bay of Quinte in the 18th century) and join up at their table, after which we all order Hot Browns. We talk about the history of American whiskey, including the connections between the Overholts, Beams, and Booths, all of whom had connections with our own personal histories.

I drive back to the Seelbach around 10:30 and unpack my stuff. Amazingly, I actually get to sleep at a fairly decent hour... THIS TIME.

MOTORCOACH MONDAY about 8:00 am...

After a morning health walk to a nearby CVS store for

"essentials" I hopped on the bus before it left at around 8:30.

Our friend Molly Wellmann joined me on this trip.

Our first stop: Maker’s Mark Distillery in Loretto.

The busload of visitors are divided into two groups. Ours is lucky enough to have Dave Pudlo, Maker's Mark's Distillery Education Director, as our guide.

Dave is not

normally called into service as a tour guide. We could only wish those whose

roles are normally tour guides (here and at other distilleries as well) had his talents. As Linda and John, we’ve visited

Maker’s Mark several times, and most of the guides there are, well...

competent, if not particularly knowledgeable or exciting. Mr. Pudlo, on the

other hand literally bursts with infectious enthusiasm and an intense

knowledge of every aspect of how Maker’s Mark is made. This becomes even more

evident when one realizes that he is fielding questions from a group of people

who make whiskey, who know what’s real and what’s marketing hype, and how to

tell the difference. And there is not one

person on this tour who left with

any doubt that what they’d learned was accurate and in many ways applicable to

what they were doing or intend to do. It was easily the best tour of Maker’s

Mark I’ve ever attended, and one of the best anywhere.

person on this tour who left with

any doubt that what they’d learned was accurate and in many ways applicable to

what they were doing or intend to do. It was easily the best tour of Maker’s

Mark I’ve ever attended, and one of the best anywhere.

There were two things that are a little disappointing, but unavoidable: the first being that, with a tour group of this size and our particular time constraints, the quaint and very nicely done old-time kitchen mockups, displays, cute telephone tours and such that an individual tourist might enjoy are not realistically available to group this large, and the other is that, along with the production expansion that Maker’s is currently undergoing, they are also having to gear up for much larger touring and visitor facilities. Construction of these is visually messy (especially for a plant that is so deservedly proud of its lovely and pristine setting) and made some features -- such as warehousing -- un-showable at this time. By the time you read this that should all be completed.

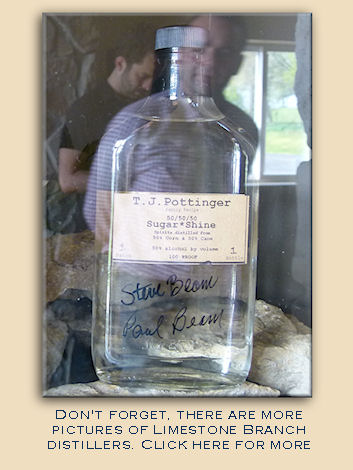

Returning to the bus, we are driven to Lebanon, about ten

miles southwest, to visit the newest member of the Kentucky Bourbon

Trail, Limestone Branch Distillers. Here we

get a chance to meet and talk with

Steve Beam and learn how a distillery dedicated to making Kentucky

farmer/distillery-style whiskey works. The building itself is a charming

combination of random-stacked and pointed fieldstone, with stainless steel

window frames, and corrugated steel siding, still shiny from being less than a

year old. And, although the history and tradition of Steve Beam and his

brother Paul runs, unobstructed, into the very bluest blood of Kentucky

bourbon distilling, they are (at least at the moment) more concerned with

producing two far more hard-core historical products, a “Moon*Shine” unaged

corn whiskey (real moonshine is untaxed -- and therefore illegal -- liquor,

not really a particular kind of liquor, but most folks unfamiliar with such

details tend call any unaged liquor “moonshine”) and what they call

“Sugar*Shine”, which is made half from corn and half from cane sugar.

Here we

get a chance to meet and talk with

Steve Beam and learn how a distillery dedicated to making Kentucky

farmer/distillery-style whiskey works. The building itself is a charming

combination of random-stacked and pointed fieldstone, with stainless steel

window frames, and corrugated steel siding, still shiny from being less than a

year old. And, although the history and tradition of Steve Beam and his

brother Paul runs, unobstructed, into the very bluest blood of Kentucky

bourbon distilling, they are (at least at the moment) more concerned with

producing two far more hard-core historical products, a “Moon*Shine” unaged

corn whiskey (real moonshine is untaxed -- and therefore illegal -- liquor,

not really a particular kind of liquor, but most folks unfamiliar with such

details tend call any unaged liquor “moonshine”) and what they call

“Sugar*Shine”, which is made half from corn and half from cane sugar.

That’s

“kinda-sorta” the way so-called “real” moonshine is made, although the product

normally emanating from illegal stills is nearly all sugar-based. That’s also

what they once called “bathtub gin” during Prohibition. The Beam brothers

don’t make that kind of stuff.

That’s

“kinda-sorta” the way so-called “real” moonshine is made, although the product

normally emanating from illegal stills is nearly all sugar-based. That’s also

what they once called “bathtub gin” during Prohibition. The Beam brothers

don’t make that kind of stuff.

What they do make, they sell under the label T. J. Pottinger, which was one of the brands produced by their great grandfather, Minor Case Beam in Nelson county. I didn’t get a chance to ask Steve about it, but I get the impression that they are also producing bourbon-recipe whiskey that will be maturing in new, charred oak barrels, and that may come into the market in several years under a different label, perhaps Old Trump, another of their great-grandfather’s brands. It gets complicated but, while the Dant family (also a major force in Kentucky whiskey history) is actually more associated with this particular area, that brand, or variations on it, is owned by at least one or two other companies and probably won’t appear on the whiskey made here. Such is the way it is with historic American spirits names. Oh well...

The operation itself is reminiscent of Paul Tomaszewski's M. B. Roland distillery in St. Elmo (Pembroke), except that Paul is exploring multiple types of unaged corn-based spirits and the Beam brothers are (at least for now) concentrating only on pure corn whiskey and more traditional "shine", which they like to call 50-50-50, as it's 50% corn, 50% sugar, and 50% alcohol (100-proof).

Our next stop, about 25 miles northwest in Bardstown,

brings us to another lovely fieldstone-and-modern distillery, of a

considerably larger scale, that is completing the metamorphosis from one highly

respected place in the American spirits world to a completely different one. What had once been the Willett distillery, high on a hill literally next door

to the original Heaven Hill distillery, had ceased actually distilling long

ago. But son-in-law Even Kulsveen reincarnated it as a producer of whiskey

from barrels purchased from several distillers, both operating and closed, and

aged in their several warehouses. Using these whiskies -- by themselves and

mixed with one another to produce specific flavor profiles, the way Scotch

whiskey once was (and still is, examples being such as Johnny Walker and Chivas Regal), Kulsveen produced fine whiskey with quite recognizable names,

for producers, many of whom would rather you believe they distilled it

themselves. Not to mention fine brands such as Rowan’s Creek, Noah’s Mill,

Pure Kentucky XO, and certainly the Willett brand itself, that they proudly

bottle under their own brand names.

Much of that development is the work of Even’s

son Drew, daughter Brit Chavanne, and her husband Hunter, all of whom work as

a team extraordinaire.

Much of that development is the work of Even’s

son Drew, daughter Brit Chavanne, and her husband Hunter, all of whom work as

a team extraordinaire.

Notice that I said “bottle”, not “distill”. Because for many years, this distillery hasn’t actually distilled any product... until now. Completely -- and impeccably -- refurbished, the Willett distillery (maybe; it’s still officially Kentucky Bourbon Distillers -- fondly known as KBD -- D.B.A. Willett Distillery, but they’re considering changing to Willett; again the details of legal definitions and intellectual property play almost as much a role as what their whiskey tastes like), is right now producing whiskey that will eventually be available as the fine, aged bourbon and rye whiskey one already expects from this company. I say “eventually” with confidence, because, delicious as the “white dog” distillate (which we got to sample) is, you won’t get to taste any of it until it passes their criteria. And that typically means many, MANY years slowly maturing in their steel-clad warehouses on the hills above Bardstown. These folks don’t rush anything, and they certainly won’t be rushing their pride-and-joy own-make spirit out the door anytime soon.

We have visited Kentucky Bourbon Distillers before. Several times, in fact. Our first experience was an hilarious (and unsuccessful) attempt to corner and talk with Even Kulsveen himself, perhaps the most reluctant interviewee we've ever (not) met. In fact, after all these years we still have never (at least knowingly) met him.

We later visited with Drew Kulsveen, and the Chavannes, Hunter and Drew's sister Brit. Click here for a special gathering in 2006 at the Bourbons Bistro in Louisville, when we opened a sealed old fiddle-shaped bottle of Old Bardstown that had been made by the Willett distillery in the early 1950s.

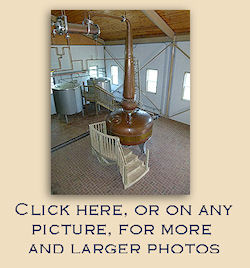

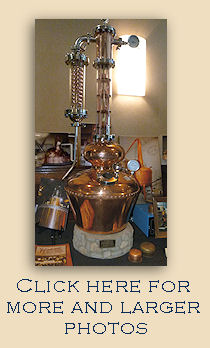

The distillery has both a stainless steel column still,

the type normally used by bourbon distillers (although most of them would

prefer to be erroneously associated with the copper pot stills used in

Scotland) and a drop-dead-gorgeous copper pot still, of the type used by many

artisan distillers, which is fitted with a dozen or so tappable plates to

provide high-precision distilling techniques not possible with a normal

single-run pot still.

The

column still, which is located in the tall, 4-story building you see behind

the grain hopper, is intended to be the workhorse still, now that that they've re-refurbished

it back to bourbon-distilling capacity. It had been converted to making

alcohol-based gasoline substitutes during the 1973 OPEC fuel crisis, and when

that emergency ended (along with the demand for gasohol) the still was shut

down, and has remained cold until this year.

The

column still, which is located in the tall, 4-story building you see behind

the grain hopper, is intended to be the workhorse still, now that that they've re-refurbished

it back to bourbon-distilling capacity. It had been converted to making

alcohol-based gasoline substitutes during the 1973 OPEC fuel crisis, and when

that emergency ended (along with the demand for gasohol) the still was shut

down, and has remained cold until this year.

In fact, it remained cold a little longer than expected, since there were some obstacles in starting it up. With a full batch of fermented mash ready to distill, Drew made the decision to set up the pot still as a column still and run the batch from there. The result is that the first sixty barrels are pure pot-distilled bourbon whiskey. Whether they will continue to produce some in that style is to be seen.

Pot stills normally use a "wash"; that is, corn, rye, and barley is cooked and mashed, then the liquid is strained off and that is what is fermented. That's how beer is made, and also how Scotch is distilled. Mash for column stills is usually fermented along with the solids, and then fed into the still solids and all. The resultant whiskies have different qualities, and having both types of still allows the Kulsveens to mix 'n' match to produce almost any flavor profile they want. Which (and yes, we're guessing here; but it's a pretty educated guess) will almost certainly include whiskey flavors never enjoyed before.

The number of people attending the conference this year necessitated two separate tours. The other bus visited different distilleries and attractions, but we all met here at Kentucky Bourbon Distillers, so Drew and Hunter have to coordinate two split busloads (that's four large tour groups), going in different directions and exchanging "tour guides" at strategic points along the way. Certainly not a job that I would want to be responsible for, but in the end everyone is safely back on his/her own bus and we are on our way to...

LUNCH!!!

Amber, our ADI tour guide/coordinator, has been taking orders for lunch during the ride. I kid her about whether she’ll be delivering them via the kind of aisle-width carts they use in airplanes, but the fact is that we will (after the bus driver dilly-dallies enough to coordinate the timing) arrive at BJ’s Restaurant & Brewhouse in Bardstown at exactly the right moment for all of our hamburgers (cooked to order) to be ready and waiting for us on the tables... and hot (and yes, some people ordered salads, but those don’t get cold, do they?) The coordination was perfect and, having been in the food-industry business in a previous lifetime, I know just how much of a coincidence that wasn’t. By the way, the ‘burgers were delicious.

Okay, even after asking Britt Chavanne, I’m not really

sure just what their new whiskey will be labeled, but there's no doubt that it

will have a very classy appearance. Their bottles will have to compete for

attention with hundreds of others, including classics they already produce.

Many, if not most, of these bottles proudly wear labels produced at the

Louisville branch (St. Louis Pressure Sensitive) facility of the larger St.

Louis Lithography Company, and to get a sense of what the process is like is the

theme for our next stop. This facility is one of the major printers of liquor labels in America,

especially spirits labels, and the team that shows us around are responsible for nearly every bourbon label

you’ve ever seen. And if you’ve seen a lot of bourbon labels, you know just

how diverse that is.

There

is virtually nothing that these folks can’t produce, in any process (or, more

likely, combination of processes) that won’t leap out at you when you see

these bottles on a liquor store shelf or when you’re scanning the back bar of

your favorite watering hole for something new and different.

There

is virtually nothing that these folks can’t produce, in any process (or, more

likely, combination of processes) that won’t leap out at you when you see

these bottles on a liquor store shelf or when you’re scanning the back bar of

your favorite watering hole for something new and different.

This is the sort of place one would certainly not expect to find listed on the Kentucky Bourbon Trail, nor would you be likely to see a "Visit a Label Printer" brochure along with the other tourist attractions in the rack at your motel lobby. In fact, I doubt that they even (normally) offer public tours. But when the American Distilling Institute sets out to provide tours of interest to its members, they typically look well beyond the normal. In this case, for example, probably well more than half of our group are planning to be needing a service such as this, and hopefully in the very near future. When you're basically hand-bottling a few cases at a time, it might not be so important where you get the labels printed, but when deciding how rapidly to expand, it's a pretty good idea to see what's available to you on a larger scale.

I say "what's available to you" because STPS doesn't

design the labels they print... exactly. You still need the services of a

graphic designer to create the signature and symbol that will represent your

product to the world. They can put you in touch with folks who do that, but

most of their customers come to them with a working label design already.

What

STPS does do, and often, is provide the technology for making that

design "pop" on the labels they produce. The judicious use of foil, multiple

layers, embossing, gloss overlays, and just about every trick in the book

becomes available to you. We are shown examples of nicely designed, but

somewhat flat labels, along with what that same design could look like with

just a little bit of pizzazz. They have computer software that can do this

from an uploaded photo, but the live example really makes it clear how

important the choice of actual printed product can be. We are taken right up

to and into the printing process and shown how it’s done, from a casual sketch

idea to the finished multi-color, multi-material, embossed, day-glow, foil,

scroll-cut label.

What

STPS does do, and often, is provide the technology for making that

design "pop" on the labels they produce. The judicious use of foil, multiple

layers, embossing, gloss overlays, and just about every trick in the book

becomes available to you. We are shown examples of nicely designed, but

somewhat flat labels, along with what that same design could look like with

just a little bit of pizzazz. They have computer software that can do this

from an uploaded photo, but the live example really makes it clear how

important the choice of actual printed product can be. We are taken right up

to and into the printing process and shown how it’s done, from a casual sketch

idea to the finished multi-color, multi-material, embossed, day-glow, foil,

scroll-cut label.

And we even get samples here! Yes, despite some fears that what we’ll get to taste are glue flavorings, we are, instead, offered some very refreshing sweet-tea liqueur and vodka drinks. Since the facility is not very large, but the size of our group is, we are split into sections. Our section is led by the quality control engineer, so the view she gives us of how labels are produced has a unique cast to it that (I feel) intensifies the experience even further.

We return to the Brown Hotel, miraculously on time, especially considering how many places we’ve visited today, for the banquet dinner and the ADI Internship Benefit Auction at the Brown Hotel. The dinner itself is, as has been the case every time we’ve attended an ADI event, not your average steam-table beef-or-chicken affair. What we are eating tonight is Kentucky Barbecue, which (for those of us who happen to be fans of barbecue) consists of pork (sorry, those of y’all who’re Texans) smoked slowly to perfection, and served with all the correct fixin’s for ‘Tucky BBQ. You want beef? No problem; we got that, too -- even if some of us don't think of that as “real” BBQ.

At some point I go downstairs to the Bluegrass Room, where the Kentucky Distillers Association are holding their own show. It is quite similar to the Bourbon Festival Spring Preview held in Bardstown, with individual booths for each distillery (on the Bourbon Trail, of course; such important distilleries as Buffalo Trace and Barton are conspicuously non-participatory). I have a chance to talk with Lew Bryson, Jimmy & Joretta Russell, Chris Morris, Greg Davis, Al Young, and many other old friends, sampling a lot of fine bourbon and rye whiskey.

Okay, it’s about 7 o’clock and we’re being “invited” into

the Crystal Ballroom for the ADI internship/benefit dinner. As I said before, this is

barbecue, not steamed beef, and it’s delicious. So is everything else being

served. During the dinner, the auction is being held. The very first item up

for sale is the bottle of Prerogative Rye, donated by none other than myself,

and which the auctioneer (Penn Jensen, vice president of ADI) is unaware has

been stolen. The bidding begins at three hundred dollars and quickly

progresses... until Penn has to announce that the bottle is no longer

available and the sale is cancelled. It’s hard to guess what the eventual sale

would have been, but it’s probably safe to say that it would have brought well

over $1,000, probably fifteen hundred. Sad. For whoever "obtained" it, please

understand that you're better off just opening and enjoying it -- all by

yourself-- because it won't bring anywhere near that much in a non-benefit

auction, the bottle is well-documented... and if we discover you trying to

sell it, you had better make sure your life insurance is paid up.

With the dinner and auction over, Jay Erisman, Molly Wellmann, the Duers, and I walk the four blocks to the Seelbach, where we established a table in the Seelbach Bar and are joined by another couple. The main reason we are doing this is because Molly, history-junkie and mixologist extraordinaire that she is, wants to experience a “Seelbach Cocktail” prepared at the very Seelbach Bar where it was invented. Jay treats us all to a round of these wonderful cocktails, which include bourbon and Champagne, Cointreau, and both Angostura and Peychaud’s bitters. It's a great cocktail. A little later we are joined by Lew Bryson, who is a contributor and managing editor of Whiskey Advocate Magazine. Lew is another writer from whom I've learned a WHOLE lot of everything I know about American whiskey -- especially Pennsylvania rye whiskey.

After awhile, the others left – after all, it’s pretty late and tomorrow is going to be an intense day – while two of us, myself and Jay, neither of whom have a lick of sense, decide to check out some of the more obscure offerings at the famous Seelbach bourbon bar. And beyond. We’ve moved from our table to the bar itself now, and we discover ourselves to be sitting next to Simon Difford, publisher of Class Magazine and a world-class expert on whisky. It’s the old “Wow, Mr. McCartney, yes I do remember your band” situation. And we continued to reminisce and experiment until the bar closed. Remember, I already have a room here, and Jay is walking (staggering, perhaps? Well, at least not driving) back to the Brown. By the time we’re finished, I can hardly make it up the elevator. Jay seems to be sufficiently ambulant. Not so sure about Simon, though, although he did have the sense to quit before we did.

Back in my room, I somehow manage enough foresight to phone in an order of pizza from an all-night pizzeria. That helped to absorb some of the alcohol. It also provided snack pizza for the next three days.

TUESDAY

Okay, yesterday was “see what successful commercial companies are doing”. Today is “see what YOU can be doing”.

The buses arrive at the hotel at 8:00, and you’d better have grabbed your fruit basket and found your seat.

We are headed toward

Huber Farm, Orchard, Vineyard, and

Winery -- oh, and Distillery, too, of course. The facility, which operates as

a publicly-assessable farm and vineyard, not to mention convention center

extraordinaire, is located in a drop-dead gorgeous

area of trees, clearings, lakes, creeks, and twisting roads that also features a

farm, a petting zoo, a woodworking mill, berry fields, fruit orchards, and a

winery. All are designed to be used for presentation to visitors. The orchards

and grapevines lead to the winery, and from that to distilled brandies. And

not too long after that to distilled grains and whiskey. But what really makes

Huber Starlight so desirable for us is that the whole operation is designed

for just such conferences and large events. They are staffed to handle it, and

they do so expertly. The size of our group is barely a challenge for them, and

the service is both efficient and invisible. Four busloads of sleepy morning

people arrive this morning to find coffees, juices, breads, biscuits and gravy

waiting for us. And when those are gone they just keep on bringing out more.

After breakfast, the sessions begin with the normal introductory speeches, where all the contributors are acknowledged and the glorious future of craft distilling is extolled. The keynote speaker is Phil Prichard, with whom we are well-acquainted, and who may be the best possible choice for inspiring would-be distiller/entrepreneurs.

After that, the session breaks out into more specific areas, including such things as “Creating Value for Investors”, “Whiskies of The World”, “Mashing & Distillation”, “Building Your Brand”, “Small Barrel Realities”, and “Permitting Tips & Procedures”.

And that’s just before lunch! Lunch consists of the best Kentucky-style fried chicken you’ve ever tasted, along with cole slaw, potatoes & gravy, corn, and biscuits. Eat your heart out, Colonel Sanders!

The afternoon was filled with sessions like “Maturation of Different Oak Species”, “Straight Shooting About Straight Whiskey”, “HR 777, Pros & Cons”, “Social Media and Marketing”, and “Distillery Refrigeration and Chillers”, and “Great Whiskies from ‘Down Under”.

If you never attended college, you might not be aware of just how intense a day like today can be, but if you have then you’ll know exactly how it feels...

There are lectures...

and seminars...

and labs, and panels, and study groups...

How do I get to the room where they're holding the

"Designing Your Chilling System" lab?

Has the "Barreling Techniques" discussion panel been re-scheduled?

Because if it has I'll be able to hear what Luis Ayala has to say about rum

distillation and blending.

And of course there are vendors -- lots of them. Joe and

Missy Duer are shopping for the right bottle for their Staley Mills rye and

they've certainly come to the right place. There are two conference rooms

filled with vendor booths, as well as a few more spread out in other rooms.

There must be half a dozen or more just displaying samples of bottles. Also

closures, foils, labels, and other packaging. Then there are the makers of

distilling equipment. Everything from major names like Vendome to small,

artisan-produced stills such as Hillbilly Stills. Metering and measuring

equipment, cooling equipment. Malts, yeasts, barrels. Everything and anything

a distiller or marketer could ever need -- even legal and accounting services!

services!

Missy finds the bottle she's been looking for and places an order.

And now it's time for Happy Hour and the tastings.

Holy Moly!!

When I last attended an ADI conference in Louisville, just two years ago, there were 300 or so participants. Most had at least one, maybe two or three expressions of what they were distilling, but anything they were aging was still too young to present to their peers.

This year we have over 600 participants, most of whom

have by now developed three, four, maybe half a dozen different “brands”. The

tastings are held outdoors, at several tables, and to everyone’s credit, I didn’t see a single

person barfing into the shrubbery. When one considers the opportunity for

over-indulgence, that’s truly amazing. Oh, all right, many of us had some

difficulty walking a straight line, but no one was punching one another out or

needing to call 911 for help. There is a distinct difference between

distillers of spirits and frat students who consume spirits. This event makes

such a difference quite clear. For one thing, even though everyone pours their

own, most people pour very small amounts of lots of samples, rather than a

normal ounce-and-a-half serving of any one (or two, or whatever).

Awhile ago all the distillers represented here today entered samples of their work into a contest. The judging itself took place at that time, but the results are to be presented during a banquet dinner tonight. The dinner, typical of those put on by Huber, is superb, consisting of roast prime rib, chicken, and wonderful Kentucky-oriented side dishes and desserts. The Weight-Watchers® angel who sits on my right shoulder was sobbing uncontrollably into her halo. I’m so sorry.

Not!

Awards were presented for best of this, best of that. Not

being a person who entirely believes in awards, I didn’t pay much attention to

this, but in general, the things I liked the best seemed to be the ones that

got the awards. For whatever that’s worth.

The buses come to take us away around 9:00.

We are all

really glad that we aren’t driving!

The main hotel for conference attendees is the

world-class famous Brown. The conference had a block of rooms there… and

overflowed. The secondary hotel is the equally historic Seelbach, only four

blocks away. Limo buses serviced conference attendees at both locations. When

those of us staying at the Seelbach arrived, some of the distillers began

forming little semi-private tastings of their own in discreet parts of the

lobby. I’m sure the same was going on at the Brown as well. I ran into a

couple I’d met earlier and we all ended up in an alcove where Joe Fenton, of

Dark Corner Distillery (Greenville, South Carolina) was offering up samples of

his corn whiskey, both the unaged “moonshine” type he has available for sale

and the results obtainable by using Dark Corner’s cleverly-designed

do-it-yourself aging “kit”. This consists of a small barrel into which you can

pour your own Dark Corner unaged corn whiskey and allow it to sit for anywhere

from a couple months to several years. This is perfectly legal, since the cost

of the whiskey you’re using already includes all the taxes (and is therefore

NOT “moonshine”).

Joe offers us examples of what the aged product is like.

What it is like is… delicious. DCD is on the verge of offering pre-aged

whiskey for sale. Joe won’t say when; I suppose it will be when he thinks it’s

the right time. Well, if what we’re tasting is the current status, I think

it’s the right time.

Joe offers us examples of what the aged product is like.

What it is like is… delicious. DCD is on the verge of offering pre-aged

whiskey for sale. Joe won’t say when; I suppose it will be when he thinks it’s

the right time. Well, if what we’re tasting is the current status, I think

it’s the right time.

There was also absinthe being served. For reasons that

should be obvious at this point, I’m not really positive whether that was

brought by Joe or by someone else, but I DO remember demonstrating how to use

ice water to achieve a “louche” (the desirable clouding of the drink in the

glass), and the “green fairy” effect, which is the thin, intense line of dark

green that forms just on the surface when the proper balance of absinthe and

water has been achieved. I also contributed the story, based on a quote by

Oscar Wilde, that you really need three glasses of absinthe in order to

understand the effect. What most people don’t realize is that there really

isn’t anything in absinthe that is “psychedelic”, other than the fact that it

is very strong in alcohol, about 140 proof or better, and it contains wormwood

– or rather the chemical thujone, found in wormwood – whose main function is

to promote alertness. Thus, absinthe allows you to get very drunk (you know,

the pink elephant kind of drunk), while keeping you wide awake and alert.

Since the dilution with water, and the wonderful herbal flavors that water

releases, makes it taste good and not overpowering, it’s very easy to drink,

for example, three glasses without realizing that you are consuming what

amount to just under 7 normal 1½ ounce shots of 80 proof whiskey! Of course,

the ritual of very slowly diluting each glass with melting ice helps allow the

full effect to develop, while the stimulating effect of the wormwood keeps you

from feeling like “oh, I’m getting sleepy; I’d better quit”. The total effect

is just what artists love: the freedom to look at ordinary things in

extraordinary ways, accompanied by the alertness and lucidity to write,

sketch, or photograph those ideas effectively. Of course you can get nearly

the exact same effect by drinking 135-proof George T. Stagg bourbon along with

Red Bull, but what a waste of great bourbon that would be.

Anyway, Wilde noted that “After the first glass of absinthe you see things as you wish they were. After the second you see them as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world. I mean disassociated. Take a top hat. You think you see it as it really is. But you don’t because you associate it with other things and ideas. If you had never heard of one before, and suddenly saw it alone, you’d be frightened, or you’d laugh. That is the effect absinthe has.”

Wilde never bothered to mention the inevitable hangover, of course. Neither did I. I hope everyone woke up okay on Wednesday for our 8:30 bus ride back to Huber. I mainly remember eating some cold pizza in my room later and driving to Huber the next morning in my car, since I missed the bus by a good hour and a half.

WEDNESDAY

My teeth itch.

My tongue is asleep.

Where did I put that pack of Alka-Seltzer?

What time is

it?

No, that can’t be right, can it?

Oh well, I have to check out this morning anyway.

I guess I might just as well

drive there myself, since the bus left an hour ago.

And what is surprising is that many others also have apparently decided to sit out this day. About a third or more of the original attendees have skipped today, and those who did missed some very interesting activities.

Not to mention breakfast. Late as I was in getting here, there was still hot frittata, biscuits ‘n gravy, apple juice (from apples grown here at Huber, of course), several types of breads and Danish, and coffee.

And lectures and seminars, such as

“Distillation Systems” by representatives of the Vendome Copper & Brass Works

“Automating Daily, Monthly Taxes & Reporting” for people who are basically craftspersons, not businesspersons.

“World Wide Whiskey Production and the Role of Yeast for

Scotch, Irish, Bourbon and Rum Spirits”, presented by Alltech Corporation,

producers of Town Branch Bourbon.

“Craft Malting and Floor Malting” by Andrea Stanley of Valley Malt ( who was the winner of last year’s ADI internship)

“Creating A Distilling Guild” a forum by Ryan Csanky, the executive director of the very successful Oregon Distillers’ Guild, Rob Masters of the Colorado Distillers’ Guild, and Paul Hletko of the Midwest Distillers’ Guild. I particularly regretted missing this, as I feel that such associations are the future of American craft distilling, thoughts that I contributed to the forum that I was able to attend, “The Remarkable Rise of Small Batch Bourbons”, headed by Wes Henderson of Angels’ Envy (and son of Lincoln Henderson, the (now-retired) Brown-Forman Master Distiller responsible for Woodford Reserve, and with whom we've spent many an enjoyable hour. Wes is joined by Richard Wolf, late of Buffalo Trace and now an independent consultant in the field of obtaining specialty-order whiskey for small bottlers, and John Little, Master Distiller and Vice President of Smooth Ambler Spirits.

While the concept appears to have been broader, the

subject quickly became the ethics and proper application of “sourced” whiskey

as a viable offering for distillers who wish to produce artisan or craft

products, while also needing to resolve the issue of having something to sell

to people for the first several years.

All of the gentlemen on the stage are

involved in doing just that, while taking pains to maintain their brand

integrity, and I believe the lessons learned here will be a determining factor

in the craft distilling industry for a long time, possibly forever. It will

most certainly be cause for much discussion and disagreement between new

whiskey aficionados and their more heritage-bound counterparts.

All of the gentlemen on the stage are

involved in doing just that, while taking pains to maintain their brand

integrity, and I believe the lessons learned here will be a determining factor

in the craft distilling industry for a long time, possibly forever. It will

most certainly be cause for much discussion and disagreement between new

whiskey aficionados and their more heritage-bound counterparts.

Lunch today is chicken pot pie and hickory-smoked pork. As is always true of the meals provided by Huber Starlight, it is fantastically produced and served. There were potato chips offered, but I stood strong in my dedication to good health, eschewing those salty morsels and choosing instead an equal number of macadamia nut, white chocolate chip cookies with considerably less salt. Aren’t I proud of myself? YEAH!!

Our friends Joe and Missy Duer found me in

the serving line and

invited me to join them outside on the patio to eat. Here we encountered a

totally delightful gentleman who has come here all the way from Tasmania to

show off what may be one of the most unique products we’ve ever seen. Peter Bignell operates the Belgrove Distillery on the Australian island of Tasmania.

With his thick Aussie accent and his sharp-as-a-razor sense of humor, you

might expect that he produces an all-malt beverage, such as would be called

Scotch, were that legal. But no, Pete has chosen instead to produce rye

whiskey. And not just any rye whiskey, either… Pete makes white rye whiskey

from grain that he grows and harvests on his own farm and malts himself. It is

about as close to the original Monongahela rye as you can get.

With his thick Aussie accent and his sharp-as-a-razor sense of humor, you

might expect that he produces an all-malt beverage, such as would be called

Scotch, were that legal. But no, Pete has chosen instead to produce rye

whiskey. And not just any rye whiskey, either… Pete makes white rye whiskey

from grain that he grows and harvests on his own farm and malts himself. It is

about as close to the original Monongahela rye as you can get.

But wait!

There’s More!

Peter’s farm equipment, distilling equipment, and everything else that

requires combustion is powered by biodiesel that he produces himself from

waste cooking oil from a roadhouse next to his farm.

His hot water is also

biodiesel heated. His tractors, forklift, and truck also run on biodiesel. In

fact, Peter likes to point out that the only significant material he brings to

the farm is waste cooking oil – and the only product to leave is whiskey.

His hot water is also

biodiesel heated. His tractors, forklift, and truck also run on biodiesel. In

fact, Peter likes to point out that the only significant material he brings to

the farm is waste cooking oil – and the only product to leave is whiskey.

Peter has a demonstration later this afternoon, which I attend along with Joe and Missy Duer, who are pretty much doing the same things themselves. It’s a shame that so few attendees are left, because they missed a very good presentation. I hope Peter will be here next time.

Perhaps the high point (and longest) seminar of the afternoon was Chip

Tate’s awesome introduction into the art of smelling and detecting the many

components of what most of simply lump together as “congeners”. These are the

various distinctive sub-components of ethyl alcohol that distinguish bourbon

(or rum, or malt, or rye) from neutral spirits. Each has its own flavor, good

or bad, and each evaporates at a different temperature. The art of making fine

spirit is the art of manipulating those temperatures such as to balance these

flavors and aromas. And, of course, you can’t do that if you don’t know what

they are. This afternoon, a rather large roomful of us got what might be our

first introduction to just what they are.

The tables are full of glasses, each containing a small amount of clear liquid, and each covered with a cap to prevent evaporation. During the course of the program, at least as many more will be delivered, one at a time. These are not for drinking. In fact, some of them might even be poisonous. These are for smelling and identifying.

Here is a list of some of them; please excuse the inevitable misspellings – I am a writer, after all, not a chemist....

Tate is the head distiller at Balcones Distilling in Waco, Texas, one of the most successful artisan distillers and holder of Whisky Magazine’s 2011 “Icons of Whisky” Distillery of the Year award. His “True Blue” aged corn whiskey (100% blue corn) is possibly the best American whiskey of any style that I’ve ever tasted. Two hours of exposure to just a fraction of what he works with every day tells you why. This is NOT the way the “big boys” do it. And they probably never did.

By

around 4:00, the buses are ready to return to the Seelbach and the Brown for the

final time. Since I’ve driven here myself, and I’ve already checked out of the

Seelbach, I return to the Brown, where I’ve decided to spend an additional night

visiting with Bill Owens and some of the ADI “inner circle”. Jay Erisman catches

a ride back with me, which is both fun (sharing time with Jay always is) and

comforting, as we spend much of the trip driving through torrential rainfall and

having a companion certainly made the experience less frightening.

Back at the Brown, I check into a room for the night and

then attempt to contact Bill. Turns out he is in the middle of a huge dinner in

the English Grill, to which he invites me, although at this point I really don’t

think I could eat another bite of anything. Among the people there are Penn

Jensen, the vice president of ADI and a major organizer of this event, Bill’s

friend and designer of his photography and distilling books, Nancy Fraley, Leah

Hutchinson, who puts these conferences together, and the lovely Amber

Hasselbring, who edits the ADI newsletter as well as conducting and coordinating

some of the tours. Bill arranges for everyone to meet in a secluded area of the

Brown’s lobby, which several of us do, only to find that (1) we are making the

staff nervous, as bringing in our own liquor violates some local ordinances, and

(2) Bill has now reached his “burn-out” point and needs to leave and get some

sleep. As we are now accumulating more guests,

Penn suggests we move the whole

party up to his suite, which brings on cheers from all involved (including the

relieved

hotel staff) and we proceed to do so immediately.

Penn suggests we move the whole

party up to his suite, which brings on cheers from all involved (including the

relieved

hotel staff) and we proceed to do so immediately.

By the time we reach Penn’s suite (the Mohammed Ali Suite, three rooms with signed boxing gloves, photos, books, and other paraphernalia), we are joined by Peter Bignell, our Tasmanian "devil", Adrian Panther and Brett Grinager of Panther Distillery who have brought an example of their absinthe to offer, as well as another absinthe-distiller, whose offering, while good, is no equal to the Panther folks'. Also present is the Swedish distiller of Hven, who with samples of both peated and unpeated malt whiskey aged in both American and French oak. I taste them all, especially the unpeated American oak. WOW!!!

There are many others there, including one distiller whose sample bottles are labeled simply “1”, “2”, and “3”. I think that was Nick Jones of Santa Fe Spirits, but I’m not sure. I also contributed, offering samples of Old Taylor ranging from (more or less) current back to 1989 and even 1957 to show how the same product changes over the years. I also pass around blind samples of the “unmentionable” American Four Roses blended whiskey, so beloved by Americans when Four Roses bourbon was only available overseas, and are equally enjoyed (when tasted blindly) by nearly everyone in the room. The exceptions? Our two distillers from Panther, both of whom are graciously accepting, while noting that that it lacked a strong whiskey character and displayed the sort of harshness one would normally associate with neutral spirits. Of course they could not have been more correct. Yes, the "New American Distiller" does indeed know his stuff!

I’m not sure how long the party actually lasted, but at 3:30 in the morning, we were making phone calls to my house in order to laugh at the answering machine message, and the party lasted quite awhile after that. I was not the last to go, and I think I was there until about 4:00.

THURSDAY

Some of the people were expecting to take a tour of the Lawrenceburg Indiana Distillery this morning, beginning at 8:30 in the Brown lobby. At least Bill was talking about it yesterday evening. I’m not sure how many actually made it, because by the time I got back to my room last night I neglected to put in a wake up call and slept in this morning until nearly 9:30. I considered chasing them (since Lawrenceburg is more or less on my way home), but thought better of it and simply returned home, burnt out, exhausted, and thoroughly satiated with the wonder and happiness of it all.

I TOTALLY can’t wait for the next one!

![]()

|

|

|

Story and original photography copyright © 2012 by John F. Lipman. All rights reserved. |

|